Głubczyce

Głubczyce | |

|---|---|

Reconstructed town hall and a Marian column on the main square | |

| Coordinates: 50°12′4″N 17°49′29″E / 50.20111°N 17.82472°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | Głubczyce |

| Gmina | Głubczyce |

| First mentioned | 1107 |

| Town rights | 1270 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Adam Krupa |

| Area | |

• Total | 12.52 km2 (4.83 sq mi) |

| Population (2019-06-30[1]) | |

• Total | 12,552 |

| • Density | 1,017.5/km2 (2,635/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 48-100 |

| Area code | +48 77 |

| Car plates | OGL |

| National roads | |

| Voivodeship roads | |

| Website | glubczyce.pl |

Głubczyce [ɡwupˈt͡ʂɨt͡sɛ] (Czech: Hlubčice or sparsely Glubčice, Silesian: Gubczyce or Gubczycy, German: Leobschütz) is a town in Opole Voivodeship in southern Poland, near the border with the Czech Republic. It is the administrative seat of Głubczyce County and Gmina Głubczyce.

Geography

[edit]Głubczyce is situated on the Głubczyce Plateau (Polish: Płaskowyż Głubczycki; a part of the Silesian Lowlands) on the Psina (Cina) river, a left tributary of the Oder. The town centre is located approximately 62 km (39 miles) south of Opole and just northwest of Ostrava.

History

[edit]Middle Ages

[edit]The area became part of the emerging Polish state in the 10th century. The settlement named Glubcici was first mentioned in an 1107 deed. At the time, it was a small village, dominated by a large wooden castle. It stood on the right bank of the Psina River, which according to an 1137 peace treaty between the dukes Soběslav I of Bohemia and Bolesław III of Poland formed the border between the Moravian lands (then ruled by the Bohemian dukes) and the Polish province of Silesia. The exact date of the city foundation is unknown, but it is traceable back to 1224, when the town called Lubschicz held toll rights obtained from the Přemyslid king Ottokar I.

However, in 1241 the town was devastated during the Mongol invasion. During the city's rebuilding, the left bank of the Psina was also settled, and in 1270 city rights were confirmed by King Ottokar II of Bohemia. During this time, a wall was built around the city, complete with watchtowers and a moat. A large parish church was also constructed in the town, which had been assigned by King Ottokar II to the Order of Saint John in 1259. After his defeat in the 1278 Battle on the Marchfeld, the town privileges were acknowledged by King Rudolf I of Germany. Ottokar's widow Kunigunda of Halych had a hospital erected, run by the Knights Hospitaller who established a commandry here. In 1298, the town received expanded rights from King Wenceslaus II. The privileges granted to the citizens were to serve as an example for other towns in the years that followed.

From about 1269, Hlubčice was part of the Moravian Duchy of Opava (Troppau), ruled by a cadet branch of the Bohemian Přemyslid dynasty since Nicholas I, a natural son of King Ottokar II, had received the lands from the hands of his father. Upon the death of Nicholas' son Duke Nicholas II and the division of the duchy of Opava between his heirs, in 1377, the town became the residence of Nicholas III who ruled as a Duke of Głubczyce. The town remained the seat of the Opava branch of the Přemyslids until the last Duke John II entered a Franciscan cloister in 1482. Upon his death three years later, his duchy was seized as a reverted fief by King Matthias Corvinus. In 1503 it was transferred to the Duchy of Krnov (Karniów) and the town finally lost its status as a residence.

Modern era

[edit]

While the Krnov principality was acquired by the Hohenzollern margrave George of Brandenburg-Ansbach in 1523, the Protestant Reformation reached the town. George had married Beatrice de Frangepan, the widow of Matthias Corvinus' son John; he and his son George Frederick tried to exert Hohenzollern influence in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown which from 1526 onwards were ruled by the Catholic House of Habsburg. In 1558, a Lutheran church and school were built in Głubczyce. In response to this, Franciscans and Jews were expelled from the city. During the Thirty Years' War, the city was completely destroyed, most devastatingly by Swedish forces in 1645.

After the Silesian Wars, the city came under the rule of Prussia in 1743. Leobschütz was incorporated into the Province of Silesia by 1815 and became the administrative seat of a Landkreis (district). In the 18th century, Leobschütz belonged to the tax inspection region of Neustadt (Prudnik).[2] In 1781, the town's population stood at only, 2,637. In order to accommodate the city's expansion, parts of the city's wall were torn down. The population stood at 4,565 in 1825, and 9,546 in 1870. After World War I and the creation of the Republic of Poland, the Silesian plebiscite was held in Upper Silesia. The percentage of 99.5% of Leobschütz citizens voted for Germany. A group of Polish insurgents was captured by the Germans in the town during the Third Silesian Uprising in 1921, after they escaped after attempting to blow up a railroad bridge in nearby Racławice Śląskie.[3]

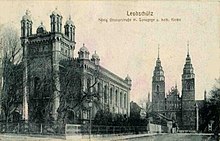

After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the town hosted schools and training grounds for both the SS and the SA paramilitary forces, becoming the honorary centre of the Nazi Party in the Prussian Province of Upper Silesia. The town's synagogue was burned down in 1938, the same year as Kristallnacht. During World War II, the Germans operated three forced labour subcamps (E247, E376, E766) of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp in the town,[4] and briefly, in January–March 1944, the Stalag 351 prisoner-of-war camp.[5] In January 1945, a German-conducted death march of prisoners of the Auschwitz concentration camp and its subcamps passed through the town,[6] and 50 prisoners of the Nazi prison in Bytom reached the town after a death march, and then were transported to Kłodzko.[7] The population was mostly evacuated before the advancing Eastern Front, with some 500 people remaining, mostly women, children, elders and ill people, seeking shelter at a local monastery.[8] After the Vistula–Oder Offensive, on 18 March 1945, Red Army troops began a siege of the town, which was resisted by the 18th SS Panzergrenadier Division (tank grenadiers) and the 371st Wehrmacht division. The siege ended on 24 March, and the Soviet forces occupied the town. Most of the women who sought shelter in the monastery were raped by Soviet soldiers.[8] Approximately 40 percent of the town was destroyed in the siege or by Red Army troopers plundering in the first weeks of the occupation.

After the Soviet occupation, the name of the town was changed to Głubczyce, a more modern version of its historic Polish name Głupczyce. The town was transferred to the re-established Republic of Poland according to the 1945 Potsdam Agreement.

After arrival of the Polish, an internment camp was created for the local populace. Those unable to work were immediately expelled to the remainder of Germany, others were forced to work for the Polish and the Soviets, before being expelled as well, in accordance to the Potsdam Agreement.[9]

New Polish settlers, some of whom refugees transferred from the Kresy in the Soviet-annexed former Polish eastern territories, made the town their home. Claims to the Głubczyce territory were raised by Czechoslovakia, which even sent troops to the area in June 1945. The border dispute around Głubczyce was eventually settled in 1958 with the Czechoslovak-Polish border agreement.[10] The town became the seat of a Polish county, or powiat, in 1946. Głubczyce lost that distinction in 1975, but regained it in 1999.

Economy

[edit]

The town of Głubczyce's economy is based around the agricultural sector and food production. Formerly, during the Polish People's Republic, the industry of fibre production developed in the settlement ("Unia", "Piast" manufacturers).[11] In modern days, the fibre manufacturing industry is near non-existent. Other industries located in Głubczyce including heating machinery production ("Galmet" and "Electromet").[12]

Population

[edit]

| Year (December 31) | Town | Gmina | County |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 13,933 | 25,565 | 54,137 |

| 2000 | 13,633 | 24,656 | 52,081 |

| 2002 | 13,633 | 24,593 | 51,675 |

| 2004 | 13,572 | 24,428 | 50,868 |

| 2006 | 13,410 | 24,102 | 50,146 |

| 2008 | 13,269 | 23,892 | 49,580 |

| 2010 | 13,157 | ? | 49,091 |

| 2012 | 13,052 | 23,270 | 47,896 |

| 2014 | 12,911 | 23,012 | 47,262 |

Climate

[edit]| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | YEAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average temperature °C (°F) | -3 (26) | -1 (30) | 1 (33) | 7 (44) | 13 (55) | 16 (60) | 17 (62) | 17 (62) | 13 (55) | 8 (46) | 3 (37) | -1 (30) | 7 (44) |

| Precipitation cm (inches) | 3.4 (1.3) | 3 (1.2) | 3.2 (1.3) | 4.1 (1.6) | 6.6 (2.6) | 7.6 (3) | 8.5 (3.4) | 7.8 (3.1) | 5.1 (2) | 4 (1.6) | 4.2 (1.6) | 3.9 (1.6) | 61.4 (24.1) |

Sports

[edit]The local football club is Polonia Głubczyce.[13] It competes in the lower leagues.

Notable people

[edit]- Karl Bulla (1855 or 1853 – 1929), German photographer, "father of Russian photo-reporting"

- Max Filke, composer

- Joachim Gnilka, theologist and biblical critic

- Heinrich Emanuel Grabowski (1792–1842), German botanist and pharmacist

- Felix Hollaender, writer and dramatist

- Gustav Hollaender (1855–1915), German violinist, conductor and composer

- Otfried Höffe, philosopher

- Erwin Félix Lewy-Bertaut, crystallographer

- Wolfgang Nastainczyk (1932–2019), German theologian

- Paul Ondrusch, sculptor

- Moritz Schulz (1825–1904), German sculptor

- Gerhard Skrobek, sculptor

- Gustav Veit (1824–1903), German gynecologist and obstetrician

- Przemysław Wacha, badminton player

- Stefanie Zweig, writer

International relations

[edit]Głubczyce is a member of Cittaslow.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]See twin towns of Gmina Głubczyce.

Gallery

[edit]-

Medieval defensive tower near Wiosenny Square

-

District Court

-

Primary School No. 2

-

Fire brigade

-

Baroque Franciscan church and monastery

References

[edit]- ^ "Population. Size and structure and vital statistics in Poland by territorial division in 2019. As of 30th June". stat.gov.pl. Statistics Poland. 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ "Historia Powiatu Prudnickiego - Starostwo Powiatowe w Prudniku". 2020-11-16. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ^ Stanisław Stadnicki. "Największy most i największa katastrofa inżynieryjna ziemi prudnickiej (część II)". Kolej Podsudecka (in Polish). Retrieved 4 January 2025.

- ^ "Working Parties". Lamsdorf.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ "The Death Marches". Sub Camps of Auschwitz. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Konieczny, Alfred (1974). "Więzienie karne w Kłodzku w latach II wojny światowej". Śląski Kwartalnik Historyczny Sobótka (in Polish). XXIX (3). Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk: 377.

- ^ a b Hanich, Andrzej (2012). "Losy ludności na Śląsku Opolskim w czasie działań wojennych i po wejściu Armii Czerwonej w 1945 roku". Studia Śląskie (in Polish). LXXI. Opole: 217. ISSN 0039-3355.

- ^ Die Vertreibung der deutschen Bevölkerung aus den Gebieten östlich der Oder-Neisse. Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa (in German). Vol. I/2. Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag. 1984. pp. 707–709.

- ^ Bahlcke, Joachim: Schlesien und die Schlesier, 2006. ISBN 3-7844-2781-2, p. 187.

- ^ S.A., eo Networks. "Strona główna - Powiatowy Urząd Pracy w Głubczycach". glubczyce.praca.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Głubczyce". www.polskawliczbach.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Polonia Głubczyce" (in Polish). Retrieved 8 May 2021.

External links

[edit]- Municipal website (in Polish)

- Jewish Community in Głubczyce on Virtual Shtetl