Friedrich Entress

Friedrich Entress | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 December 1914 |

| Died | 28 May 1947 (aged 32) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Motive | Nazism |

| Conviction(s) | War crimes |

| Trial | Mauthausen Trial |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | Thousands |

Span of crimes | 1941–1945 |

| Country | Poland and Austria |

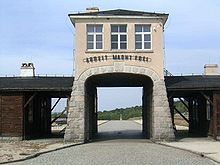

| Location(s) | Auschwitz concentration camp Mauthausen concentration camp Gross-Rosen concentration camp |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1939–1945 |

| Rank | Hauptsturmführer |

Friedrich Karl Hermann Entress (8 December 1914 – 28 May 1947) was a German camp doctor in various concentration and extermination camps during the Second World War. He conducted human medical experimentation at Auschwitz and introduced the procedure there of injecting lethal doses of phenol directly into the hearts of prisoners. He was captured by the Allies in 1945, sentenced to death at the Mauthausen-Gusen camp trials, and executed in 1947.

Early life

[edit]Friedrich Entress was born on 8 December 1914 in Posen, a Polish-Prussian province,[1] and graduated in medicine in either 1938[2] or 1939.[1] He was able to receive his doctorate in 1942 without writing a dissertation, "a privilege granted to Germans from the east".[3] He had grey eyes and dark blonde hair and was described as having a "Nordic" profile. According to Michael Kater, he was part of a vigilante group of ethnic Germans that was supported by the Schutzstaffel (SS), and after the German invasion of Poland he joined the SS-Totenkopfverbände.[1]

Second World War

[edit]

Entress departed to various concentration camps as an SS doctor,[1] starting with a post at Gross-Rosen concentration camp in 1941.[3] He was at the main Auschwitz camp between 11 December 1941 and 21 October 1943. During the last seven or eight months (March 1943 to 20 October 1943) at Auschwitz, he became camp physician at Buna-Monowitz workcamp,[4] also part of the Auschwitz camp system. Subsequently, Entress in October 1943 became senior physician at Mauthausen-Gusen, where he worked until July 1944.[1][5] Entress participated in selections for the gas chambers. For example, on 29 August 1942 in Auschwitz, he and Josef Klehr selected 746 prisoners to be gassed under the guise of fighting a typhus epidemic.[6]

On the death toll among inmates at Monowitz, where IG Farben had manufacturing facilities, Entress later commented, "The turnover of inmates in Monowitz was enormous. The inmates were weak and malnourished. It should be emphasised that the performance demanded of the inmates was not in accord with their living conditions and nutrition".[5]

He conducted human medical experimentation at Auschwitz, along with Helmut Vetter and Eduard Wirths,[7] where he operated in "Block 21" and was paid by the Bayer pharmaceutical subsidiary of IG Farben to test experimental drugs against typhus and tuberculosis (TB).[4]

Experiments included collapsing the lungs of people with TB. Establishing a TB ward, he perfected the technique before killing all those on the ward by injecting lethal doses of phenol directly through the chest wall and into the victims hearts,[8] allowing up to 100 people to be killed each day.[3] He became a key player in the organisation and administration of killings by phenol.[4][9] The practice may have been used to cover up the results of experimental medical procedures, including surgery, that he and other doctors at the camp carried out despite not having surgical qualifications.[7][10] In 1942, he gave Bayer associate Helmut Vetter approval to test TB drug Rutenol, an arsenic acid derivative.[8]

Josef Mengele, who had arrived at Auschwitz in May 1943, five months before Entress left for Mauthausen-Gusen, carried on TB work at Auschwitz from 1943.[4][8] At one time, Czech doctor Karel Sperber worked under Entress. In July 1944, Entress returned to the Gross-Rosen camp. On 10 February 1945, he left the camps to serve as a surgeon for the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen.[11][12]

Capture and death

[edit]Entress was taken prisoner in Austria in May 1945. He was transferred to a prison in Gmunden in July. After becoming aware of what he'd done, U.S. officials transferred him to a court they had established in the former Dachau concentration camp to stand trial. Entress was one of 61 defendants in the first mass Mauthausen-Gusen camp trials in 1946. Entress did not testify in his own defense.[13]

Multiple witnesses said Entress and another SS physician, Waldemar Wolter, participated in the selections of approximately 3000 prisoners. On 11 May 1946, all 61 defendants in trial, including Entress, were found guilty of war crimes. Two days later, Entress and 57 other defendants were sentenced to death.[1] Several months later, Entress filed for clemency, as did his wife on his behalf. In an affidavit filed about two weeks before a clemency decision was issued, Entress stated that he was obeying orders to select sick prisoners and knew those he had selected would be gassed.[14]

The clemency report on the 61 defendants was issued on 30 April 1947. Of those condemned to death, clemency was denied to 49 convicts, including Entress. Having lost their appeals, all but one of the 49 convicts (one person won a last-minute stay of execution, and was hanged separately in June) who were denied clemency were hanged at Landsberg Prison between 27 and 28 May 1947. Entress was hanged on 28 May. [13][15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Kater, Michael H. (1989). Doctors Under Hitler. USA: University of North Carolina Press. p. 73. ISBN 0-8078-1842-9.

- ^ Weindling, Paul (2015). Victims and Survivors of Nazi Human Experiments: Science and Suffering in the Holocaust. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-4411-7990-6.

- ^ a b c Francis R. Nicosia; Jonathan Huener (2002). Medicine and Medical Ethics in Nazi Germany: Origins, Practices, Legacies. Berghahn Books. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-57181-387-9.

- ^ a b c d Bacon, Ewa K. (2017). Saving Lives in Auschwitz: The Prisoners Hospital in Buna-Monowitz. Purdue University Press. p. 38. ISBN 9781557537799.

- ^ a b Tully, John (2011). The Devil's Milk: A Social History of Rubber. Monthly Reviews Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-58367-231-0.

- ^ "Auschwitz Memorial / Muzeum Auschwitz – August 29, 1942 | SS garrison doctor Kurt Uhlenbroock ordered a selection at the camp infirmary under the pretext of fighting the typhoid epidemic. Prisoners were placed in the corridors and stairs leading to the closed courtyard between blocks 20 and 21 in the Auschwitz I camp. The selection was carried out by SS physician Friedrich Entress and paramedic Josef Klehr. As a result, 746 prisoners were taken by trucks to Birkenau, where they were killed in gas chambers the same day. | Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ a b www.auschwitz.org. "Other doctor-perpetrators / Medical experiments / History / Auschwitz-Birkenau". auschwitz.org. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Murray, J.F.; Loddenkemper, R. (2018). Tuberculosis and War: Lessons Learned from World War II. Karger. p. 54. ISBN 978-3-318-06095-9.

- ^ Barr, Robert (2017). Where Is the World Going?. Dorrance Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4809-3796-3.

- ^ Gutman, Israel; Berenbaum, Michael (1994). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Indiana University Press. p. 262. ISBN 0-253-20884-X.

- ^ Weindling, Paul (2017). From Clinic to Concentration Camp: Reassessing Nazi Medical and Racial Research, 1933-1945. Routledge. ISBN 9781317132394.

- ^ "Entress Friedrich Dr". www.tenhumbergreinhard.de. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ a b United States vs. Hans Altfuldisch et al Case No. 000-50-5. Commander in Chief European Command, 1947. p. 28. via jewishvirtuallibrary.org Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Nuremberg – Document Viewer – Affidavit concerning the euthanasia program, the extermination of the Jews, and medical experiments conducted in the concentration camps". nuremberg.law.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ^ Dȩbski, Jerzy. (1995) Death Books from Auschwitz: Remnants – Volume 1. K.G. Saur. p. 251. ISBN 9783598112621

External links

[edit]- 1914 births

- 1947 deaths

- 20th-century surgeons

- Auschwitz concentration camp medical personnel

- Executed German mass murderers

- German surgeons

- Gross-Rosen concentration camp personnel

- Holocaust perpetrators in Austria

- Holocaust perpetrators in Poland

- Mauthausen Trial executions

- Nazi human subject research

- People from Posen–West Prussia

- SS-Hauptsturmführer

- Waffen-SS personnel