Fordcroft Anglo-Saxon cemetery

The location of the cemetery | |

| Location | Orpington, London Borough of Bromley |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°23′19″N 0°06′26″E / 51.388608°N 0.107218°E |

| Type | Anglo-Saxon inhumation and cremation cemetery |

Fordcroft Anglo-Saxon cemetery was a place of burial. It is located in the town of Orpington in South East London, South-East England. Belonging to the Middle Anglo-Saxon period, it was part of the much wider tradition of burial in Early Anglo-Saxon England. Fordcroft was a mixed inhumation and cremation ceremony.

Archaeologists affiliated with the local Orpington Museum began excavating in 1965, expecting to find evidence of Romano-British occupation, but after discovering the cemetery decided to focus on it. Excavation continued for four seasons, ending in 1968.

Location

[edit]The site was located in Orpington, close to the border with St Mary Cray. It sits between Bellefield Road and Poverest Road, near to the junction with the A224 road.[1] The source of the River Cray lies half a mile south of the cemetery, while the river itself passes by 200 metres away from the site.[2] The plot of land on which it was discovered was 1/8 of an acre in size.[2] The soil is largely brick-earth, resting on the Flood Plain gravel which covers the valley floor.[2]

The nearest settlement that is known to be long-established is the farmstead of Poverest, the name of which can be traced to the early-14th century.[3] The area remained agricultural land lying between the two villages until the mid-19th century, when increasing development led to the area becoming suburban.[2] Several Victorian cottages had been built atop the cemetery, but were demolished during the following century, when the site became "overgrown with weeds and littered with rubbish" prior to excavation.[2]

Background

[edit]

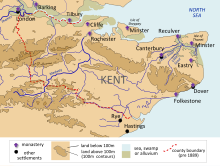

With the advent of the Anglo-Saxon period in the fifth century CE, the area that became Kent underwent a radical transformation on a political, social, and physical level.[4] In the preceding era of Roman Britain, the area had been administered as the civitas of Cantiaci, a part of the Roman Empire, but following the collapse of Roman rule in 410 CE, many signs of Romano-British society began to disappear, replaced by those of the ascendant Anglo-Saxon culture.[4] Later Anglo-Saxon accounts attribute this change to the widescale invasion of Germanic language tribes from northern Europe, namely the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.[5] Archaeological and toponymic evidence shows that there was a great deal of syncretism, with Anglo-Saxon culture interacting and mixing with the Romano-British culture.[6]

The Old English term Kent first appears in the Anglo-Saxon period, and was based on the earlier Celtic-language name Cantii.[7] Initially applied only to the area east of the River Medway, by the end of the sixth century it also referred to areas to the west of it.[7] The Kingdom of Kent was the first recorded Anglo-Saxon kingdom to appear in the historical record,[8] and by the end of the sixth century, it had become a significant political power, exercising hegemony over large parts of southern and eastern Britain.[4] At the time, Kent had strong trade links with Francia, while the Kentish royal family married members of Francia's Merovingian dynasty, who were already Christian.[9] Kentish King Æthelberht was the overlord of various neighbouring kingdoms when he converted to Christianity in the early seventh century as a result of Augustine of Canterbury and the Gregorian mission, who had been sent by Pope Gregory to replace England's pagan beliefs with Christianity.[10] It was in this context that the Polhill cemetery was in use.

Kent has a wealth of Early Medieval funerary archaeology.[11] The earliest excavation of Anglo-Saxon Kentish graves was in the 17th century, when antiquarians took an increasing interest in the material remains of the period.[12] In the ensuing centuries, antiquarian interest gave way to more methodical archaeological investigation, and prominent archaeologists like Bryan Faussett, James Douglas, Cecil Brent, George Payne, and Charles Roach Smith "dominated" archaeological research in Kent.[12]

Cemetery features

[edit]The Fordcroft cemetery contained a mixture of cremation and inhumation burials.[13] The two forms of burial were interspersed within the cemetery, leading excavators to believe that they were contemporary with each other.[13] Archaeologists have discovered a total of 19 cremations and 52 inhumations from the site.[14] Due to the grave goods found at the site, Tester suggested that the site was probably active as a place of burial between circa 450 and 550 CE.[15] He noted that culturally, the artefacts and forms of burial were similar to those found around the Thames Valley.[16]

There is evidence of nearby Romano-British occupation, which numismatic evidence shows extended to at least c. 370.[16] and Tester suggested that the Anglo-Saxons might have intentionally adopted Fordcroft as a cemetery site because of this. Equally, he thought it possible that the reuse of the site was simply fortuitous.[16]

Many of the skeletons were heavily decayed, although in many cases the teeth and long bones were sufficiently preserved for osteoarchaeologists to determine the age and sex of the individual.[17] Most of the inhumation graves had the head facing westward, though in some cases they instead faced south.[13] Most of the grave cuts were roughly rectangular with rounded corners, but some were less regular in form.[17] Due to 19th century construction on the site, it was impossible for the archaeologists to accurately determine where the Anglo-Saxon ground level had been, and therefore how deep the graves had been cut.[13]

Archaeological investigation

[edit]In the 1940s, a service trench had been excavated in the adjacent Bellefield Road by workmen, who revealed pieces of Romano-British pottery. Archaeologist A. Eldridge published this discovery in the Archaeologia Cantiana journal, suggesting that there might have been a building dating to Roman Britain nearby.[2] In the 1960s, local archaeologists decided to test this theory by investigating the derelict site at Fordcroft following the demolition of the houses on that site.[2] Test excavation took place at the site from July 1965, sponsored by Orpington Museum, under the authority of the London Borough of Bromley, to whom the site legally belonged.[18] The borough council provided a mechanical digger to remove surface rubble, allowing excavation to commence.[18] Much of the investigation was organised by M. Bowen, curator of Orpington Museum, where the site finds were initially stored.[18]

The first archaeological discoveries at the site were Romano-British in origin, although no evidence of buildings from this period were discovered. Soon, an Anglo-Saxon cremation urn was found, followed by several inhumations, revealing that this had been the site of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery. Thenceforth, the excavation of the cemetery became the primary objective of the archaeologists.[2] In the first two-seasons' work, 16 cremations and 29 inhumations were discovered.[13] At the time of its discovery, it was recognised as the first "well-authenticated" archaeological evidence for Anglo-Saxon settlement along the River Cray.[18] Elderly members of the community who had formerly lived in the cottages on the site visited the excavation, providing "likely and amusing comments" following the revelation that they had dwelt above a cemetery.[17]

A test pit was opened in the garage of No. 17 Poverest Road, uncovering another grave, and it is believed that further burials might be located under the house.[19] The team excavated all available areas, although were unable to dig under either of the roads enclosing the site, or under the houses to the east and west.[20]

See also

[edit]- List of Anglo-Saxon cemeteries

- Buckland Anglo-Saxon cemetery

- Finglesham Anglo-Saxon cemetery

- Polhill Anglo-Saxon cemetery

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Tester 1968, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tester 1968, p. 126.

- ^ Tester 1968, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b c Welch 2007, p. 189.

- ^ Blair 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Blair 2000, p. 4.

- ^ a b Welch 2007, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Welch 2007, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Welch 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 14.

- ^ a b Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e Tester 1968, p. 127.

- ^ Tester 1969, p. 40.

- ^ Tester 1968, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Tester 1969, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Tester 1968, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Tester 1968, p. 125.

- ^ Tester 1968, p. 130.

- ^ Tester 1969, p. 39.

Bibliography

[edit]- Blair, John (2000). The Anglo-Saxon Age: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192854032.

- Brookes, Stuart; Harrington, Sue (2010). The Kingdom and People of Kent AD 400–1066. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5694-2.

- Tester, P.J. (1968). "An Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Orpington: First Interim Report". Archaeologia Cantiana. 83: 125–150.

- Tester, P.J. (1969). "Excavations at Fordcroft, Orpington: Concluding Report". Archaeologia Cantiana. 84: 39–77.

- Tester, P.J. (1977). "Further Notes on the Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Orpington". Archaeologia Cantiana. 93: 201–202.

- Welch, Martin (2007). "Anglo-Saxon Kent to AD 800". In J.H. Williams (ed.). The Archaeology of Kent to AD 800. Rochester: Kent County Council. pp. 187–250.