Folklore of the Low Countries

Folklore of the Low Countries, often just referred to as Dutch folklore, includes the epics, legends, fairy tales and oral traditions of the people of Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg. Traditionally this folklore is written or spoken in Dutch or in one of the regional languages of these countries.

Folk traditions

[edit]The folklore of the Low Countries encompasses the folk traditions of the Benelux countries: Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. This includes the folklore of Flanders, the Dutch-speaking northern part of Belgium, Frisia, Luxembourg and Wallonia.

Fairy tales

[edit]Many folk tales are derived from pre-Christian Gaulish and Germanic culture; as such, many are similar to French and German versions. In 1891, schoolteacher Jules Lemoine and folklorist Auguste Gittée published Folk Tales from the Walloon Country. They focused on strictly transcribing and translating tales from original Walloon manuscripts, mostly from Hainaut and Namur.[1] In 1918 William Elliot Griffis published Dutch Fairy Tales for Young Folks:[2] This was followed in 1919 by Belgian Fairy Tales.[3] Also in 1918, Belgian writer Jean de Bosschère published Folk Tales of Flanders (published in English as Beasts and Men). The Belgian tale "Karl Katz" is similar to both the German folk tale "Peter Klaus" and Washington Irving's "Rip Van Winkle". Charles Deulin was a French writer, born near the Belgian border. He wrote stories based on the folk tales of the countryside.[4] The Nettle Spinner is a Flemish fairy tale later included in Andrew Lang's 1890 The Red Fairy Book.

Dutch Fairy Tales for Young Folks

[edit]

Among the stories are:

- The Entangled Mermaid

- The Boy Who Wanted More Cheese

- Prince Spin Head and Miss Snow White

- The Boar with Golden Bristles

- The Ice King and His Wonderful Grandchild

- The Elves and Their Antics

- The Kabouters and the Bells

- The Woman with Three Hundred and Sixty-Six Children

- The Oni on His Travels

- The Curly-Tailed Lion

- Brabo and the Giant

- The Farm that Ran Away and Came Back

- Sinterklaas and Black Pete

- The Goblins Turned to Stone

- The Mouldy Penny

- The Golden Helmet

- When Wheat Worked Woe – a version of Lady of Stavoren, or The Most Precious Thing in the World

- Why the Stork Loves Holland

"The Little Dutch Boy" is commonly thought to be a Dutch legend or fairy tale, but is in fact a fictional story, Hans Brinker or the Silver Skates, written by American author Mary Mapes Dodge, and not known in the Netherlands as traditional folklore.[6]

Themes

[edit]Some old stories reflect the Celtic belief in the sacredness of trees.[citation needed] The oak as a venerable tree is a theme seen in the stories. In The Princess with Twenty Petticoats, a wise old oak counsels the king; in The Legend of the Wooden Shoe, another consoles a carpenter.

Dutch folk tales from the Middle Ages are strong on tales about flooded cities and the sea. Legends surround the sunken cities lost to epic floods in the Netherlands: From Saint Elisabeth's Flood of 1421, comes the legend of Kinderdijk that a baby and a cat were found floating in a cradle after the city flooded, the cat keeping the cradle from tipping over. They were the only survivors of the flood. The town of Kinderdijk is named for the place where the cradle came ashore.[7] The story is told in The Cat and the Cradle.

The Saeftinghe legend, says that once glorious city was flooded and ruined by sea waters due to the All Saints' flood, that was flooded in 1584, due to a mermaid being captured and mistreated, and mentions the bell tower still rings. This is much like the story The Mermaid of Westenschouwen (Westenschouwen) which also concerns the mistreated mermaid, followed by a curse and flood.[7] In some flood legends, the church bells or clock bells of sunken cities still can be heard ringing underwater.

De Reis van Sint Brandaen (Dutch for The Voyage of Saint Brandan) is a sort of a Christianized Odyssey, written in the 12th century that describes the legend of Sint Brandaen, a monk from Galway, and his voyage around the world for nine years. Scholars believe the Dutch legend derived from a now lost middle High German text combined with Celtic elements from Ireland and combines Christian and fairy tale elements. The journey was begun as a punishment by an angel. The angel saw Brandaen did not believe the truth of a book on the miracles of creation and saw Brandaen throw it into the fire. The angel tells him that truth has been destroyed. On his journeys Brandaen encounters the wonders and horrors of the world, people in distant lands with swine heads, dog legs and wolf teeth carrying bows and arrows, and an enormous fish that encircles the ship by holding its tail in its mouth. The English poem Life of Saint Brandan is an English derivative.[8]

Sea folklore includes the legend of Sint Brandaen and later the legend of Lady of Stavoren about the ruined port city of Stavoren.

Flemish Fairy Tales

[edit]- Farmer Brooms, Farmer Blisters and Farmer Iron

In literature

[edit]Romances

[edit]The first written folklore of the Low Countries Carolingian romances about Charlemagne ("Karel" in Dutch). Karel ende Elegast (Charlemagne and Elegast) is a Middle Dutch epic poem written around the end of the 12th century or early 13th century. It is a Frankish romance of Charlemagne ("Karel") as an exemplary Christian king and his friend Elegast, whose name means "elf spirit" or "elf guest." Elegast has supernatural powers such as the ability to talk to animals and may be an Elf. He lives in the forest as a thief. The two go out on an adventure and uncover and do away with Eggeric, as a traitor to Charlemagne.[9]

Fables

[edit]Van den vos Reynaerde (About Reynard the Fox) is the Dutch version of the story of the Reynard the fox by Willem, that derives and expands from the French poem Roman de Renart. However, the first fragments of the tale were found written in Belgium. It is an anthropomorphic fable of a fox, trickster. The Dutch version is considered a masterpiece, it regards the animals' attempts to bring Reynard to King Nobel's court, Reynard the fox outwits everyone in avoiding being hung on the gallows.[10] The animals in the Dutch version include: Reinaerde or Reynaerde the fox, Bruun the Bear, Tybeert the Cat, Grimbeert the badger, Nobel the lion and Cuwaert the Hare.

Dutch folklore also concerned the Christian saints and British themes of King Arthur chivalry and quests:

Tales of saints and miracles

[edit]Biographies of Christian saints and stories of Christian miracles were important genre in the Middle Ages. Original Dutch works of the genre are:

- Het Leven van Sint Servaes (Dutch for The Life of Saint Servatius), was a poem written circa 1160-1170 by Hendrik van Veldeke, a Limbourg nobleman, is notably the first literature on record written in Dutch. This is an adaptation of the Latin, Vita et Miracula.[11]

- Beatrijs (Dutch for Beatrice), written in the last quarter of the 13th century, possibly by Diederik van Assenede, is an original poem about the existing folklore of a nun who deserts her convent for the love of a man, and lives with him for seven years and has two children. When he deserts her, she becomes a prostitute to support her children. Then she learns that Mary (mother of Jesus) has been acting in her role at the convent and she can return without anyone knowing of her absence. This legend is the Dutch adaptation of the Latin, Dialogus Miraculorum of 1223 and Libri Octo Miraculorum of 1237.[12]

- Mariken van Nieumeghen is an early 16th century Dutch text that tells the story of Mariken who is seduced by the devil (named Moenen). He promises to teach her all the languages of the world and the 7 arts (music, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, grammar, logic, and rhetoric). Later she repents and performs acts of penitence.

According to Griffis, mythology of Wodan on the Wild Hunt sailing through the sky, is thought to have been one of the tales that changed into tales of Christian Sinterklaas traveling the sky.[3] Zwarte Piet (Dutch for Black Pete) is his assistant.

Arthurian romance

[edit]- Roman van Walewein is a notably original poem written in Dutch by two authors Penninc and Pieter Vostaert[13] and is a story of Walewein (Dutch for "Gawain"), one of King Arthur's knights on a series of quests to find a magical chessboard for King Arthur.

- Lancelot is a translation from British Arthurian romance.

- Perceval is a translation from British Arthurian romance.

- Graalqueeste (Dutch for Quest of the Grail) is a translation from British Arthurian romance.

- Arthurs Dood (Dutch for Arthur's Death) is a translation from British Arthurian romance.

Folk art

[edit]Folk art can also be seen in puppet and marionette theatres. The story of Genevieve of Brabant, a virtuous wife wrongfully accused of infidelity, was first presented in 1716 in Brabant. In the mid-18th century, it became very popular among traveling puppet companies.[14]

Customs

[edit]"Dutch ethnologists view community festivals and holidays as the most active and conspicuous living tradition in the Low Countries."[15]

The gift of a pewter or silver spoon to commemorate the birth of a child was traditional.[16]

Folk songs

[edit]The subject matter of the oldest Dutch folk songs (also called ballads, popular songs or romances) is very old and can go back to ancient fairy tales and legends. In fact, apart from ancient tales embedded in the 13th century Dutch folk songs, and some evidence of Celtic and Germanic mythology in the naming of days of the week and landmarks (see for example the 2nd century inscription to goddess Vagdavercustis), the folk tales of the ancient Dutch people were not written down in the first written literature of the 12th century, and thus lost to us.

One of the older folk tales to be in a song is Heer Halewijn (also known as Van Here Halewijn and in English The Song of Lord Halewijn), one of the oldest Dutch folk songs to survive, from the 13th century, and is about a prototype of a bluebeard. This song contains elements mythemes of Germanic legend, notably in "a magic song" within a song, that compares to the song of the Scandinavian Nix (strömkarlen), a male water spirit who played enchanted songs on the violin, luring women and children to drown.[17]

Other folk songs from the Netherlands with various origins include: The Snow-White Bird, Fivelgoer Christmas Carol, O Now this Glorious Eastertide, Who will go with me to Wieringen, What Time is It and A Peasant would his Neighbor See. Folk songs from Belgium in Dutch include: All in a Stable, Maying Song ("Arise my Love, Shake off this Dream") and In Holland Stands a House.[18]

Folklore from the Middle Ages

[edit]

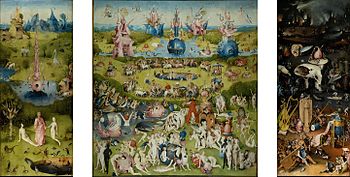

The paintings of Pieter Brueghel the Elder from North Brabant, show many other circulating folk tales, such as the legend of Dulle Griet (Mad Meg), 1562. Jheronimus Bosch (or Jeroen Bosch) is a world famous draughtsman and painter from North Brabant. He painted several mythical figures that he placed in heaven or hell. Examples are the tree man, The Ears with the knife, The Devil on the chair, The Choir Devil and The Egg monster.

Legendary people

[edit]

- Arumer Zwarte Hoop (The Arumer Black Gang), a select group of highly specialized and legendary warriors, led by Grutte Pier

- Baron and Baroness of Ever – a fictional title in the Langstraat region; nationally known by the former amusement park 'Land van Ooit'

- Beatrijs – an errant nun alleged to be saved by Mary (mother of Jesus). See tales of saints & miracles

- Brandaen – a monk from Galway who takes a voyage around the world for 9 years (epic poetry)

- Dieske – a legend in the city of 's Hertogenbosch; he alerts the arrival of the enemy, while he was urinating in the canal

- Dulle Griet (Mad Meg) – the legendary mad woman

- Ellert and Brammert - giant highway robbers.

- Finn (Frisian) – Frisian lord, son of Folcwald

- Flying Dutchman – a pirate and his ghost ship that can never go home, but are doomed to sail "the seven seas" forever; note this legend originated in England theater; according to some sources, the 17th century Dutch captain Bernard Fokke is the model for the captain

- Giant Brothers Dan, Toen, Ooit and Nu – Many stories exist around these 4 giants. They enjoy national fame through the premiere amusement park 'Land van Ooit'.

- Governor of ever – a fictional character in the Langstraat region

- Jan Klaassen – a trumpet player from the army from the village Andel

- Jan van Hunks – alleged Dutch pirate whose soul was taken by the devil after beating the devil at pipe-smoking contest on Table Mountain, and Devil's Peak (Cape Town), South Africa. Whenever a cloud appears of Table Mountain it is said that van Hunks and the devil are at it again.

- Jarpisser – a historical figure from the city of Tilburg who collects his urine in a jar for the ammonia

- Jokie de Pretneus – the fictional jester famous of the cartoons in The Netherlands and Belgium

- Knight Granite – a strong fictional Knight from the Langstraat region

- Ing (Ingwaz, Yngvi) – founder of the Ingaevones, son of Mannus

- Istaev, founder of the Istvaeones, son of Mannus

- Kloontje The Giant Child – a fictional Giant Child who eats a huge amount of ice cream

- Kobus van der Schlossen, a Robin Hood-like character

- Little Father Bidou

- Lohengrin – the son of Parzival (Percival), in Arthurian legend

- Liudger – a missionary among the Frisians and Saxons

- Mannus – ancestor of a number of Germanic tribes, son of Tuisto

- Saint Martin of Tours

- Pardoes – a fictional jester and wizard who has enjoyed national fame since 1989, immortalized in a statue in amusement park the Efteling

- Pardijn – a fictional jester and Princes, who has enjoyed national fame since 1990

- The Gang of the White Feather – a former real-life robber gang from the North Brabant 'Langstraat region' is still often mentioned in stories

- The Gang of Oss – a real robber gang was active from 1888 until 1934. The gang is mostly romanticized in the North Brabant and some compare it with Robin Hood's gang

- The Peat ship of Breda – this ship's ruse was used to recapture Breda from de Spanish empire

- Pier Gerlofs Donia "Grutte Pier" – a Frisian pirate and freedom fighter (known for wielding a 2.15 meter sword, and able to behead several enemies at the same time), who was around 7.5 feet in tall

- Reintje The Fox or Reinaart the fox – a fox from fables, fairy tales, rhymes and songs; a statue stands in Zealand, in the town of Hulst

- Saint Radboud – bishop of Utrecht from 900 to 917, grandson of the last King of the Frisians

- Saint-Jutte – a fictional saint; the priest of Breda said: "Carnival will return to Breda during the Mass of Saint Jutte," which actually meant that it would 'never' come back.

- Tuisto (Tuisco) – the mythical ancestor of all Germanic tribes

- Thyl Uylenspiegel – 1867 novel by Charles De Coster recounts the adventures of a Flemish prankster during the Reformation wars in the Netherlands

- Walewein (Dutch for "Gawain") – a knight in Arthurian legend

- Witte Wieven - stories of "wise women" date back at least to the 600s. In some places they were known as Juffers or Joffers ("ladies"). Historically, the witte wieven are thought to be wise women, herbalists and medicine healers.

- Zwarte Piet

Legendary creatures

[edit]

- Alves – Small nature spirits or earth men; according to the myths they would live on the surface; usually they are shown squatting and walking on hands and feet.

- Beeldwit – a good witch without evil intentions; mostly found on wheat fields

- Elves – female winged light spirits originating from Germanic and Norwegian mythology. Moss Maidens were known as tree spirits or wood elves.

- Boeman – the bogeyman of the Netherlands

- Bugbear

- Druon Antigoon – a giant from Brabo and the Giant[19]

- Dwarfs – a short, stocky humanoid creature

- Gnomes – dwarf-like beings who instruct the kabouters in smithing and construction. They design the first carillons (groups of bells) of the Netherlands – from The Kabouters and the Bells[19]

- Goblins – or sooty elves, have both dwarf and goblin traits, from The Goblins Turned to Stone[19]

- Kabouter – (Dutch for gnome) short, strong workers. They build the first carillons (groups of bells) of the Netherlands – from The Kabouters and the Bells[19]

- Nuton - (Walloon for Kabouter but with similar linguistic roots to lutin). Nutons share the same origins as elves, but caves, caverns and underground tunnels form the bulk of their habitat according to local folklore, more alike to the dwarves of the Germanic world.

- Klaas Vaak (Dutch version of the "Sandman")

- Lange Wapper (also known locally as the "Longue Schlongue") is a Flemish legendary giant and trickster whose folk tales were told especially in the city of Antwerp and its neighbouring towns.

- The Mark – a night demon of Walloon areas of Belgium and Flander's borders

- Mara – from Scandinavian countries, a malignant female wraith who causes nightmares

- Macralle – Macralle is a word from Liège Walloon designing a witch. Also a malignant female, she is said to be responsible for many painfull events, such as winter.

- Nicker – a water spirit

- Nightmares – female horses who sit on people's bellies at night after they've eaten toasted cheese; female goblins in their true form; from The Goblins Turned to Stone[19]

- Ossaert – a mocking water spirit – invented by adults to keep children safely away from water

- Pig-faced women

- Plaaggeesten – a kind of teasing ghosts without human souls; demonic beings that have always existed

- Puk (Dutch for puck)

- Staalkaar – Stall Elves who live in animal stalls[19]

- Styf – an elf who invents starch, from The Elves and Their Antics[19]

- Dwaallichten – from The Elves and Their Antics[19]

- Waterwolf – an example of animalisation (link lifeless things to a dangerous animal). The rough waves from the sea, which is a constant threat to the low country, is given the name 'Waterwolf'.

- Werewolf – the Germanic and Norwegian variant of the Greek Lycan; the Werewolf would need the full moon to change shape. There are stories about Werewolfs in the towns of Loosbroek and Vught.[20] In some stories a connection is made with the Beeldwit.

- Witte Wieven (dialectal, meaning "white women") – similar to völva, herbalists and wise women

Mythological deities

[edit]From ancient regional mythology, names of ancient gods and goddesses in this region come from Roman, Celtic and Germanic origins.

Legendary places

[edit]- Cockaigne (also called Luilekkerland) – Dutch for "lazy luscious land", a "land of plenty".

- Saeftinghe legend

- The legend of St Gotthard Pass – a Devil's Bridge folktale

Other folklore

[edit]- Doed-koecks (Dutch for dead-cakes) – a food closely related to the folklore of funeral customs

- Oliebollen (Dutch doughnut) – a Yule food related to the folklore of Berchta

- Public holidays in the Netherlands

- Wellerism

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Contes populaires du pays wallon / Par Auguste Gittée,... Et Jules Lemoine,... ; illustrations de J. Heylemans. 1891.

- ^ Griffis, William Elliot. Dutch Fairy Tales for Young Folks, 1918

- ^ a b Griffis, William Elliot, Belgian Fairy Tales, 1919

- ^ Malarte-Feldman, Claire L. (12 February 2016). Duggan, Anne E.; Haase, Donald (eds.). Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from around the World. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-61069-254-0. OCLC 923255058.

- ^ Gombrich, E. H. "Bosch's 'Garden of Earthly Delights': A Progress Report". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Volume 32, 1969: 162–170

- ^ Margry, Peter Jan. "Ethnology and Folklore in the Netherlands", World Encyclopedia on Folklore, 2005

- ^ a b Meder, Theo.

- ^ Meijer 1971:9.

- ^ Meijer 1971:7-8.

- ^ Meijer 1971:3-4, 23-24.

- ^ Meijer 1971:4.

- ^ Meijer 1971:20-21.

- ^ Meijer 1971:11.

- ^ "Geneviève de Brabant", World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts

- ^ Bronner, Simon J., "Dutch Tolerance and Tension in Folklore", The Practice of Folklore, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2019ISBN 9781496822642

- ^ "Customs, Cooking, and Folklore", New Netherland Institute

- ^ Meijer, page 35.

- ^ These songs are collected with the melody score in Folk Songs of Europe edited by Karpeles.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dutch Fairy Tales for Young Folks by William Elliot Griffis

- ^ Oe toch, spookjes en sprookjes uit het Brabantse Maasland, Gerard Ulijn, ISBN 90 6486 010 6.

Sources

[edit]- Studies

- Encyclopedia Mythica.

- Dekker, Ton; Kooi, Jurjen van der; Meder, Theo, eds. (1997). Van Aladdin tot Zwaan kleef aan. Lexicon van sprookjes: ontstaan, ontwikkeling, variaties (in Dutch). Kritak: Sun.

- Kooi, Jurjen van der (1984). Volksverhalen in Friesland: lectuur en mondelinge overlevering: een typencatalogus (in Dutch). Stichting Ffyrug/Stichting Sasland.

- Meder, Theo. Dutch folk narrative. Meertens Instituut, Amsterdam. File retrieved 3-11-2007.

- Meijer, Reinder. Literature of the Low Countries: A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1971.

- Meyer, Maurits de. Les contes populaires de la Flandre: apercu général de l'étude du conte populaire en Flandre et catalogue de toutes les variantes flamandes de contes types par A. Aarne. Folklore Fellows Communications n:º 37. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. 1921.

- Compilations of tales

- de Cock, Alfons [in Dutch]; de Mont, Pol (1896). Dit zijn Vlaamsche wondersprookjes, het volk naverteld. Gent: A. Siffer.

- Goyert, Georg (1917). Vlämische Sagen: Legenden und Volksmärchen; mit 16 alten Ansichten (in German). E. Diederichs.

- Griffis, William Elliot. Dutch Fairy Tales For Young Folks. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1918. (English). Available online by SurLaLane Fairy Tales. File retrieved 1-17-2007.

- Griffis, William Elliot. Belgian fairy tales. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell company. [1919?]

- Karpeles, Maud, editor. Folk Songs of Europe. New York: Oak Publications, 1964.

- Kooi, Jurjen van der (1990). Friesische Märchen [Frisian Fairy Tales] (in German). München: Diederichs Verlag.

- de Meyere, Victor. De Vlaamsche vertelselschat. Vol. I, II, III, and IV (Animal Tales). 1925-1933 (1ste druk).

- Ridder, André de. Christmas tales of Flanders. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1917.

- Wolf, Johann Wilhelm. Deutsche Märchen und Sagen. Leipzig: 1845.