Földes

Földes | |

|---|---|

Large village | |

Church | |

| |

| Country | |

| County | Hajdú-Bihar |

| District | Püspökladány |

| Area | |

• Total | 65.23 km2 (25.19 sq mi) |

| Population (1 January 2015) | |

• Total | 3,980 |

| • Density | 60.59/km2 (156.9/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 4177 |

| Area code | (+36) 54 |

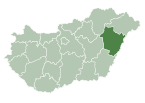

Földes is a large village in Hajdú-Bihar County, in the Northern Great Plain region of eastern Hungary.

Location

[edit]It covers an area of 65.23 km2 (25 sq mi) and has a population of 3,960 people (2016). It is located next to the main road 42 between Püspökladány and Berettyóújfalu, 34 km southwest of Debrecen. The Eastern Main Channel is 5 km northeast from Földes. Directly neighboring settlements: Sáp (4 km south), Báránd (10 km southwest), Tetétlen (5 km west), Hajdúszovát (14 km northeast), Derecske (20 km east), Berettyóújfalu (16 km southeast). A bus service connects to Debrecen, Berettyóújfalu, Püspökladány, Kaba, Nagyrábé. The closest train station is located in Sáp.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

In 1938, traces of the first human settlement were found during archeological excavations in the Inacs Mound, next to the main road 42, at the western edge of Földes's boundary. It was a Neolithic site where the remains of their pit houses and burned walls of their wattle-and-daub were found with the tools of a copper-age man. Lajos Kiss and Béla Kálmán[1] linguists declared, the village was named after its soil. György Módy historian said, that the name of the village origined from personal name and perhaps got it from its inhabitants dealing with farming.[2] Földes also had a tradition of its own name-origin, spreading by László Virágh a teacher from Földes.[3]

The first written mention of Földes – which was debated for a long time[4] – was in the Váradi Regestrum in 1215: messenger Gyuro, the son of Moysa from Heldus (Földes) village (pristaldum nomine Gyuro, filium Moysa de villa Heldus), proceeded in an affair of peoples from Bajom and Rábé. From that time on, the name of Földes did not appear in written sources until 1342, but an interesting tradition (story) has survived from 1241 to 1242.[5] Rogerius a canon of Várad wrote about this period, telling what devastation the Southern Tatar army had done under Kadan's leadership in Bihar County.

An entirely sure mentioning of Földes[6] was on 31 May 1342, when in the report of the Eger chapter to Hungarian King Károly Róbert, András the son of Tamás from Földes, appears as a noble witness (Andreas filius Thomae de Feldes). Tamás and his son András were the first known members of the Földesi family. The members of this family were the landlords of Földes. They took their family name after the name of the village. From Földes, only the names of this family members can be found in the documents until the end of the 15th century. Not much later in the same year, in 1342, archdeacon Jakab from Földes and his brother Benedek were also mentioned. In 1399, Imre the son of Péter (calling to bald) from Földes, together with Tamás and János the sons of Mihály also from Földes, had mixed up with culprits, and were convicted for decapitation and loss of their wealth. They were at last convicted for proscription. Since they had been avare of their guilt they did not attend the county assembly.

1400 at the end of July, Hungarian King Zsigmond appointed Péter the son of János from Földes, to a royal man for border control together with others. In the Autumn of 1400, Földes the village was mentioned for the first time in a diploma of Rábé family. One part of the family's estates was towards Földes (…a parte possessionis Feldes nominate). In 1405 Benedek magnus Nagy from Földes and Tamás Nagy and András Nagy were sub-prefects of Szatmár County. According to Kálmán Baán (genealogist, heraldist) this Benedek the magnus was the founder and eponym of the Földesi Nagy family. In 1407 Vince Földesi (Vincetius de Felwdessy) a royal man. He was the first member of the family whose family name was already evolved. In 1417 Benedek Földesi Nagy (Benedictus magnus de Feldes) was appointed to a palatine man. According to searches of József Csoma (historian, heraldist), in 1449 János Hunyadi donated bodily coat of arms for several members of the family. The Földesi family used the family name Szentmiklósi[7] too, depending where the locations of their estates were. In 1459 Adorján Földesi (Adriani litterati) appeared in the suit of an estate who bore a name scrivener which supposes higher education. In 1465 some members of the Földesi Nagy committed murders against other noble men. King Mátyás those who had committed the murders convicted for beheading and loss of their wealth. He donated their assets to the families of Bajon, Sztári and Parlagi. In 1483 the Várad chapter for the command of King Mátyás, designated among others István Földesi[8] to a royal man. He had to cite into law with three times shoutings István Szakolyi, who had estates among other villages also in Hosszúmacs (today a part of Debrecen). The Bajons and Sztáris after they had got their domains did not stay in the village, procurators handled their lands from the families of Harangi and Simai. There was no peace between the Földes nobles and the procurators of the estates. In 1489 and 1510 they had still agreed, but in 1516 the Földes nobles attacked the country-seats of the families of Harangi and Simai in Félhalom in Békés County.

Because of these affairs at the beginning of the 16th century there were credible data about 30 Földes nobles who had one plot. On May 7, 1537, King János Szapolyai had issued a decree, confirmed with it the organized community of Földes nobles against Szabolcs County.[9] This diploma was good for them as proof in later times, in the protection of local authority over the noble privileges, against Szabolcs County and other powerful warlords. In 1549 they were included in two censuses.[10] Between 1552 and 1570, because of the wars against the castles had been launched by the Turks, the village got under Turkish rule. It was constantly menaced from Turkish-Tataric forays, destructions.[11] In 1566, around November 19, the village was saved from a Turkish-Tartaric destruction. At that time from this countryside, thousands of people, including residents of Földes too, were dragged away to Szolnok into captivity. After the Treaty of Speyer (1570), which followed the Treaty of Adrianople (1568), the village returned to the jurisdiction of Szabolcs County. In 1572, the name of Földes appeared in a Turkish Treasury poll tax list (defter). The tax book listed 39 houses and taxpayers' names without mentioning the church.[12][13] From 1571 the records of the county contained a series of small and large trials of the nobles of Földes and Sáp until 1582. In 1582 Földes came under Turkish rule, Turkish administration was introduced, but it only existed between 1582 and 1584. In 1583 Transylvanian Prince Zsigmond Báthory[14] donated destroyed estates in the borders of Földes and Szentmiklós, to János Paksy in a princely donation letter.[15]

1600 until the Revolution

[edit]From 1600 after the Battle of Mezőkeresztes (1596), the southern part of Szabolcs County was a completely abandoned, conquered area by the Turks, where tax collectors didn't try to collect taxes. There were no data from Földes, except those who moved to Debrecen. In 1616 among the villages belonging to Bajom Castle the name of the village was visible, but there was hardly anyone left from the old landowners in it. Földes together with Szabolcs County at that time were a collision place among the Royal Hungary, Principality of Transylvania and the Turkish Empire. After the Peace of Nikolsburg (1621) the village belonged to Transylvania. On 3 July 1624 the Prince of Transylvania Gábor Bethlen commanded the Estates of Bihar County to produce under oath a truthful testimony records of the nobles' privileges of Földes and Sáp. After the execution it was released by the Várad Chapter on 11 June 1625. After the death of Gábor Bethlen (1629), as it was described in the Peace of Nikolsburg, Szabolcs County with Földes and 7 Tisza counties were connected to the Royal Hungary, but in 1645 they returned under the power of György I Rákóczi Transylvanian Prince. On September 23, 1645, a Letter of Defense was gained from György I Rákóczi against of wandering soldiers, including the recognition and strengthening of their noble privileges too. First time the seal of Földes stamped in wafer appeared in 1652 on a letter to Szabolcs county with a circumscription: The Seal of Földes. It was under Turkish rule that the two noble villages with full legal authority Földes and Sáp, had made each other's courts as an appeal authority and they worked so until 1735. After György II Rákóczi's campaign to Poland, the Turkish launched a revenge offensive in early April 1660. Szejdi Ahmed the pasha of Buda destroyed the areas of Hajdúk (peasant freelance soldiers) in Szabolcs and Bihar Counties. This affected Földes mainly after the fall of Várad,[16] when the villages of Szabolcs and Bihar Counties were distributed as tributes among the fighting Turks. The heavy taxes and cruel treatments had forced the population to flee to the neighboring counties, from where they came back to their own lands after the Peace of Vasvár (1664). This is why Mátyás Nógrádi the Bishop of Tiszántúl and the pastor of Nagybajom wrote in the introduction of his book, The gateway of salvation (Idvesség kapuja):...Földes Sáp Konyár and Bajom are damaged locations (…Fődeske, Sáp, Konyár és Bajom megromlott helyecske). Mihály Rápóti's diary attested that in 1678 the population of the village had consisted of 79 families which had meant about 320 people. In 1679 the plague was so huge that it had exterminated more than half of the population and only 31 families survived it. Prior to the Turkish final expulsion the tribulations were intensified. The attacks of Turkish, Tartaric, Kuruc (Hungarian rebel), Labanc (German loyal to emperor) troops had forced the people living here to escape again and again, but their own landownership always brought them back. In those times however Mezőszentmiklós was forever abandoned.

The first thing of the villagers after the Turkish times was to procure another privilege letter from the King of Hungary Lipót I (Habsburg) what he gave out for them on 2 October 1692 in the castle of Ebersdorf. They had to obtain newer privilege letter during the Rákóczi's War of Independence. Prince Ferenc II Rákóczi gave them two confirmatory diplomas: one in Tokaj on 28 October 1703 and the other in Eperjes on 5 March 1708. After the return of the Habsburg rule the following privilege letter was given by Károly III on 22 July 1718 in Vienna. The Hungarian translation of this have been preserved by many families in Földes until today. Then Szabolcs County had launched lawsuits against the village and the nobles which were being lasted more than fifty years. These were the following ones. Lawsuites of examinations of noble origin (1725–38), in which one joint noble privilege letter was not enough for the all noble men, but everybody had to prove his noble origin one by one. Lawsuit for the election of Lieutenant of the village (1731–33). Lawsuit for the right to use broadsword (jus gladii) (1731–1746). Lawsuit because of ferry-fees, customs, thirtieth customs, ecclesiastic tithe (1743–1774). The last lawsuit was for the legal authority of the village (1758–79). The villagers of Földes won this lawsuit with the verdict of the Seven-Person Board on 13 February 1776. The fighting between the powerful Szabolcs County and Földes the small noble village was completed. The parties had been tired of the fighting, three years later on 15 April 1779 without any external pressure, they jointly created the Regulation of Földes village[18] for the exercise of the local laws, which was in effect until 1848. Currently Földes Day is on 14 April.[19][20] The large village remembers back on Földes Day to the nobles of the settlement, who created their old organisations, resisted to Szabolcs County, protected their privileges outwardly and within the village they provided civilian equality.

Hungarian revolution onwards

[edit]| legitimate voters | in population | |

|---|---|---|

| Egyek | 195 | 8.2% |

| Földes | 702 | 29.7% |

| Kaba | 236 | 10% |

| Nádudvar | 485 | 20.5% |

| Püspökladány | 313 | 13.2% |

| Tetétlen | 149 | 6.3% |

| Tiszacsege | 287 | 12.1% |

In the Revolution and War of Independence (1848–49) about 225 residents participated from Földes. First in April 1848, 138 recruits joined the movable National Militia. The recruits of the local National Militia had stayed home and defended the village. Later in June 8, in October 45, in November 34 recruits joined the National Militia. From there the militiamen were continuously redirected to the National Army.[21] In 1871, Földes was transformed from a well-organized village to a large village. One half of its Representative Body consisted of elected members, the other half of (virilis) most tax payers. In 1876 it was attached to the newly established Hajdú County. With this, the 800 years relationship with Szabolcs County ceased. First the village was linked to the Nádudvar district, then to the Hajdúszoboszló, at last to the Püspökladány district. At parliamentary elections it usually belonged to the Nádudvar district. The noble heritage of the village can be seen in the Election Registers of 1877 and 1879,[22] when the election legitimacy nationally was 6–7% due to restrictive conditions in the laws.

In the last decades of the 19th century the consolidation of the fragmented lands became inevitable. The border of Földes had more than 10,000 morgens and consisted of thousands of parts at the beginning of the 1880 years. The consolidation of the lands had been first come up in 1867 and after series of lawsuits was ended in 1897. Another enormous task was the draining of the internal waters at the early 20th century. In 1904, first in the northern part of the Földes border a canal was made in the bed of the Hamvas rill, together with the surrounding area water management. In 1914, the water of the dead river Kálló was drained with the lengthening of the Sárrét channel. The storey building of the Községháza (Village House) which can be seen today was being built between 1924 and 1927.[23]

In the World War I ca. out of 900 soldiers of the village 306 became heroic dead. In the Temple Garden the village erected a statue for the memory of the heroic deads in 1924. Another memorial was erected by the village in 1990 for the remembrance of the 352 heroic dead soldiers and residential victims of the World War II.

| based on | people | % |

|---|---|---|

| noble origin | 582 | 90 |

| land | 35 | 5.4 |

| income | 18 | 2.8 |

| schooling | 11 | 1.7 |

In 1925, Lajos Zoltai – a scholar of Debrecen past and was born in Földes – participated in excavating the past of the neighborhood. He revealed in the Kis-Andaháza meadow, adjacent to Földes's border, the foundation of Andaháza's temple which had been built at the beginning of the 12th century.[24] The book of Gábor Herpay: History of Földes Village (1936) was the first, comprehensive summary of the village's past.[25]

In October 1944, 15 Hungarian, 6 Russian and 20 German soldiers died in Földes and its surroundings in the fightings.[26] Magistracy escaped but on October 22, with the leader of the Deputy Chief Judge, the population began the cleaning of the ruins. On November 27, public administration was resumed, in December police were organized with seven policemen and with 370 the Social Democratic Party's local organization was formed. The National Committee commenced its operation on January 15, 1945, assumed the organization of the supply of the population, the launch of work in all areas, and the inter-party negotiations. The largest party was the Independent Smallholders' Party at all the two (1945 and 1947) free elections. The Land-Claiming Committee allocated 1,239 morgans to 348 landless people. In 1949, the introduction of electric lighting had been begun, which was completed in 20 years. In 1968, the drinking water pipeline system of the village was made. After that the replacement of the basic institutional background was accelerated, the modernization of the village and the improvement of the quality of life began. The first agricultural cooperative was organized in the village in 1949. By the end of the 1950s, after the disappearances, transformations and mergers, the Rákóczi and Lenin cooperatives remained. In the 1960s, the larger Rákóczi won a nationwide reputation.

Reformed Church

[edit]

There are no data about Földes's ecclesiastical life in the Middle Ages. Földes, before the Reformation, belonged to the Diocese of Eger along with the neighboring villages of Szabolcs County. In the second half of the 16th century, after 1557, the inhabitants of the village converted to the Reformed faith when the Reformed Church had finally been established and consolidated in Debrecen. After the Reformation, Földes was a part of the Reformed Diocese of Debrecen. The first reliable data can be found in 1597 about the existence of the Földes Reformed Church. At that time, the Debrecen Council ruled on the divorce case of a pastor named Mihály from Földes and declared the husband guilty in the divorce lawsuit, not allowing him to divorce from his wife.[27]

- Temple building and tower

In 1621, there was temple but there were only a small number of people of the Földes Church because it had only a pastor but not a rector or teacher. Even so, the Church of Földes was a Mother Church and Tetétlen as a Daughter Church (filialis) without temple was attached to it. In 1713, a bell tower was built, near the temple building. In 1769 the church building was enlarged and in 1770 the bell tower was raised. The church building was extended from 10 fathoms to 11 and a half fathoms and the width from 3 fathoms to 6 fathoms. The bell tower was raised from 10 fathoms to 11 fathoms and the width remained 10 fathoms. The extension of the old church building was necessary, because it had only 383 places for 1,073 believers and 690 people were left outside. In 1818, the number of believers was 3,000 and the number of places in the church building was again low. In the same year, a lightning struck the tower and the church building, and the damages had to be repaired. Between 1822 and 1828, the building of the church was extended from 11 and a half fathoms to 18 and a half fathoms. Between 1830 and 1834 the bell tower was built together with the church building and raised from 11 fathoms to 21 fathoms high. The next enlargement was taken place in 1884. At that time the number of Calvinist believers was 4,384. In 1910, the wooden beam bearing the tower ball and tower star on top of the tower had to be replaced.[28] Then the church was repaired in the 1930s, 1970s and 1990s. In 2004, the wooden beam that had been put up into the tower in 1910 and it had held the tower ball and star, it had been broken and it was exchanged. In 2010 the walking surface of the church was changed for brick coverage. During its most recent partial renovation in 2020, the tower cover was changed from red copper to zinc, the church roof from galvanized sheet-iron to red roof tiles.

- Bells

The bell tower was built in 1713. In 1770 when the bell tower was being raised, two bells were removed from the old tower and then placed in the new tower. One of the bells was made in 1744 and the other was made in 1758 and each had a weight of 3 Vienna centner (168 kilograms). These bells were replaced in 1868 with 3 new bells. The new bells were made by Ignácz Hilzer in Bécsújhely and were put up into the tower by József Pozdeck Budapest.[28] The big bell 16 Vc (907 kg) and the middle bell 9 Vc (528 kg) were taken to war in 1917. Instead them, the Church had two new bells made in 1923. The new big bell was 855 kg and the new middle bell was 517 kg and have remained until today. The 283 kg small bell made in 1868, it had been cracked and was replaced in 1998 by a 260 kg bell had been made by Lajos Gombos in Őrbottyán.

- Tower Clock

The village had it made in 1778 and commissioned György Földessy, a clock master, to care for the tower clock and paid for it. In 1870, the clock machine was amended with a quarter-hour instrument by Sándor Körvélyessy clock master and Ferencz Körtvélyessy smith master. In the cost of the 450 florins modification, the Földes Jewish residents provided 40 florins.

- Church Organ

The first donation for the building of the church organ was donated by Gábor Sápy and his wife, Eszter Szabó, in 1884, with 10 pieces of Körmöc gold. The donations were assembled by the intervention of pastor Ferenc Kiss, and in 1894 the church organ was made by József Angster a Pécs organ builder.

Temple Garden

[edit]In 1896, after the initiation of pastor Ferenc Kiss, with the work of the village residents, the memorial garden[28] before the temple was formed for the memory of the Hungarians incoming a thousand years before. Memorials are in the Temple Garden evoking the past.

-

Memorial 1848–49

-

World War I Memorial 1914–18

-

World War II Memorial 1939–45

-

Kopjafa Memorial 1956

-

Temple Garden

Jewry

[edit]

Jakab Herskowicz was the first Jew who temporarily lived in Földes. His name was among the tenants in Nagykálló in 1734, as a resident of Földes. Some years later he was a resident in Nagykálló according to the documents. During the reign Emperor József II (1780–1790) at a census Jews were not found in the village. No Jewish residents paying tolerance tax can be found in 1798, in the documents on Tolerance Taxes of the Council of Lieutenancy. In the first third of the 19th century there were sporadic, inaccurate figures about the number of Jews. In the censuses of Szabolcs County can be found some data. Out of the records of religious affiliation of the Diocese of Eger, most of the Jewish data from the 19th century have remained chiefly.

| years | people | origins of data | years | people | origins of data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1798 | no | tax authority | 1849 | 156 | Eger Diocese |

| 1816 | 5 | Szabolcs County | 1851 | 160 | Eger Diocese |

| 1816 | 5 | Eger Diocese | 1853 | 78 | Eger Diocese |

| 1820 | 37 | tax authority | 1857 | 111 | Eger Diocese |

| 1822 | 9 | Szabolcs County | 1861 | 156 | Eger Diocese |

| 1830 | 21 | Szabolcs County | 1865 | 163 | Eger Diocese |

| 1835 | 156 | Eger Diocese | 1900 | 345 | national census |

| 1838 | 161 | Eger Diocese | 1930 | 269 | national census |

| 1845 | 172 | Eger Diocese | 1941 | 237 | national census |

| 1846 | 182 | Eger Diocese | 1944 | 214 | census |

| July 1848 | 163 | national Jewish census[29] | after war | 50 | World Jewish Congress |

| End 1848 | 179 | Eger Diocese | 1957 | 10 |

According to old documents,[30][31] the Orthodox community was founded in the early 1800s. In 1820, they had a prayer house and a ritual bath. The Orthodox community founded Talmud Torah school and yeshiva (Talmud school) at the beginning. In 1820 they paid 160 florins tolerance tax. In 1821 Áron Schwarz was the teacher. In 1825 the Földes Council punished the Jewish teacher (preceptor) because of the complaint of Ábrahám Vidszik tailor. On Sunday, July 12, 1835, noble György Gáll had gone into the Jewish temple[32] and drove out the believers, the teacher, and the students. The noble Council had noble György Gáll made into shackles after the complaint of József Weinberger the representative of the Jewish community. In 1844, noble Sándor Ványi rented 1,400 morgens of land with a Jew. In 1845, a new temple had been built[30][31] from the voluntary donations of the community members, which was in later times enlarged. In 1848, Bertalan Szemere, the Interior Minister of the Revolutionary Hungarian Government, ordered a national Jewish census. At that time Mózes Epstein was the teacher. During the 1848–49 War of Independence the Jewish community had to send 3 soldiers to the army. In January, 1849, when weapons were being gathered, from 191 weapons, seven were handed in by Jews. After the fall of the War of Independence, during the Austrian absolutism, the number of Jews fell to 78 in 1853, rising to 156 by 1861. In 1851 the rabbi Mihály Csillag (1811–1891) had lived on a plot where in 1857, according to the Cadastral Record, the Synagogue of the Földes Israelis was. At that time the Jewish community's 750 square fathoms cemetery was on the part of the border called Sziget, where it is still today. In 1867 the National Assembly adopted the Jewish emancipation law.

In 1871, after the Orthodox Judaism had been separated, Földes remained an Orthodox community. In 1873, Mór Fischer had a licensed Jewish private school, while at the same time József Goldstein and Jacob Glück were not allowed the teaching in their schools with Jewish religion. In 1876 the community founded elementary school with 1 teacher and 80 students. The teacher had not had a qualification from the National Israelite Teachers College[33] and the school had to be closed. In 1883, the school had been re-opened with the certified Ferenc Fischer teacher who remained in Földes until 1901. In the elementary school, cheder (religion teaching) was held in a separate room that the melamed (religion tutor) taught. In 1903, 60 Jewish traders and craftsmen were registered in the Debrecen Chamber of Commerce and Industry.[34] In 1913 the elementary school moved to a new, hygienic building.[30][31] In 1914 it had 60 students. In the World War I (1914–18), 50 members of the community participated and six lost their lives. In the 1920s Jewish youth played an active and prominent role in the local sport life. Football (soccer) was built primarily on them. The Nyúl brothers had played in the MTK[35] and they also got to the Hungary national team. In 1929[30][31] the members of the community were 253 people, the number of families was 60, and the tax was paid by 55 people. By occupation: 1 teacher, 34 merchants, 15 artisans, 1 entrepreneur. The Talmud Torah and the yeshiva religious schools were active, the elementary school had 35 students. The rules of operation of Chevra Kadisa[36] were approved by the Interior Ministry in 1898. They spent 9% of the budget of the community for charitable purposes. Sáp and Tetétlen also belonged to Földes's register. After the outbreak of the World War II, 65 men had been called in a labor service that 33 survived. In 1944, after the occupation of Germans, 214 Jews were included in the list. Földes Jews had been transported to the Püspökladány ghetto on 19 May 1944 and by the end of June they were transported to Debrecen. The train fittings were launched in Auschwitz on the 25th from the Debrecen brick factory.

In 1990, the names of 193 Jewish residents were written on the Memorial of World War II, who had lost their lives in the war. After the war, the survivors returned to the village for more or less time. According to the World Jewish Congress, the members of the Orthodox Jewish community at this time were 50, and its chairman was Ernő Lefkovits. There were regular church worships in the temple, there was a permanent kosher butcher, ritual bath, Talmud Torah teaching. Subsequently, as a result of the emigrations, in 1957 there were only 10 Jewish residents in the village. In 1958 the temple was broken down, and the purchase price of the demolition material was written, according to the disposition of the MIOK,[38] to the account of the expired community. Today, some pictures, commemorative writings in local history books, the cemetery in the old Sziget area and the names on the memorials in the Templomkert (Temple Garden) are the reminders of the former Jewish population of Földes.[39]

Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 4,560 | — |

| 1880 | 4,547 | −0.3% |

| 1890 | 4,814 | +5.9% |

| 1900 | 5,137 | +6.7% |

| 1910 | 5,539 | +7.8% |

| 1920 | 5,439 | −1.8% |

| 1930 | 5,669 | +4.2% |

| 1941 | 5,776 | +1.9% |

| 1949 | 5,889 | +2.0% |

| 1960 | 5,415 | −8.0% |

| 1970 | 5,159 | −4.7% |

| 1980 | 4,950 | −4.1% |

| 1990 | 4,598 | −7.1% |

| 2001 | 4,350 | −5.4% |

| 2005 | 4,241 | −2.5% |

| 2009 | 4,092 | −3.5% |

| 2011 | 4,062 | −0.7% |

| 2013 | 4,069 | +0.2% |

| 2014 | 3,996 | −1.8% |

| 2015 | 3,980 | −0.4% |

| 2016 | 3,960 | −0.5% |

The population of the settlement increased steadily from 1880 to 1949, and gradually decreased from 1949 to the present day.[40] In 2011 there were 3,623 Hungarians, 45 Gypsies, 12 Germans, 9 Bulgarians, 5 Romanians and 23 other nationalities in the population of the settlement.[41]

Village Border

[edit]The major part of Földes's border is good quality plough-land suitable for agricultural cultivation. In the eastern and southeastern parts of the border, pastures and saline areas are parts of the Bihar Plane Landscape Protection District. In the border, there are mounds remained from the past which are called Kunhaloms.

- Kunhalom is the name of artificially created land hills in the Great Hungarian Plain of the Carpathian Basin. These mounds were created in different eras. The collecting word of Kunhalom includes the burial-mounds (kurgans), the dwelling-mounds, the lookout-mounds and the border-mounds. The name Kunhalom (Cuman Mound) in the literature was first used by István Horvát historian at the beginning of the 19th century, because he attributed these formations to the work of the settlers of the Cuman people. From the point of view of cultural heritage, landscapes, flora and fauna, Kunhaloms represent considerable values. In the border of Földes the following Kunhaloms were in 1890: Inacs, Csőre, Szil, Szél, Ritó, Veres, Mogyorósi, Small Gyepáros, Gyepáros, Telek, Csoma, Kettős, Páka, Small Gyilkos, Gyilkos, Dinnyás, Small Nyáros and Great Nyáros Mounds.[42] Today only the Inacs, Gyepáros, Telek, and the Gyilkos Mounds are not under agricultural cultivation.[43]

-

Inacs Mound

-

Gyepáros Mound

-

Telek Mound or Temple Hill[17]

-

Gyilkos Mound

-

Mogyorósi Mound

-

Csoma Mound

-

Kettős (Double) Mounds

- The Bihar Plane Teaching Nature Path is located in the Földes border, and it is the part of the Bihar Plane Landscape Protection District, in the northern part of the Great Sárrét, once rich in marshes. Various scapes and habitats, typical of the Bihar Plane can be found on the marked route. Smaller and bigger mowings, pastures, forest patches and shrubs change each other. A glimpse can be gained at the Andaháza habitat reconstruction to the wildlife of wetlands, swamps, marshes and canals. In addition to many common species, there are few, highly protected living creatures along the way. A grazing buffalo herd have a big role in maintaining the habitats here. Two observation towers and presentation boards help the visitor's discovery. There are more than 100 species on the twenty boards, with brief description.[44][45]

- Anglers' pond. The bed of the anglers' pond was created in 1992 with the help of the Rákóczi Agricultural Cooperative. The cooperative gave the 10 hectares of land next to the Eastern Main Channel that was inadequate for the growing of agricultural crops and an old reedy area was there.

-

Eastern Main Channel

-

Anglers' pond

Sights

[edit]- Reformed Church

- Village House built 1924–27

- Memorial 1848–49

- World War I Memorial 1914–18

- Trianon Memorial 1920

- World War II Memorial 1939–45

- Kopjafa Memorial 1956

- Memorial exhibition of Sándor Karácsony in the Village Library

- Memorial Wall of Sándor Karácsony

- Kállay Country House and community space

- Székely Gate of the Carpathian Basin Bridesmen

- Kopjafa of the Carpathian Basin Bridesmen

- Memorial Fountain

- Memorial Tablets

- Lajos Zoltai

- János Balásházy

- István Jámbor

- László Kállay

- Bihar Plane Teaching Nature Path

-

Székely Gate

-

Bridesmen Kopjafa

-

Memorial Fountain

-

Trianon Memorial 1920

Thermal Bath and Leisure Center

[edit]

The thermal water comes from the nearby well which was drilled in 1967. It comes up from 1,344 meters deep and the outlet temperature is 64 °C. It has salinity, alkali chloride, iodine and bromine. It is for the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Thermal water will not only be used for bathing. It is used to heat the kindergarten and nursery, the school and community center, and the Village House.

Famous people

[edit]- Sándor Karácsony (1891–1952) He was born in Földes. He was a pedagogical, philosophical writer, university professor. In the place of his birth house there is today one of the two buildings of the primary school of Földes. The school and the cultural center took up the name of Sándor Karácsony.[46][47]

- János Balásházy (1797–1857) He died in Földes. He was a regular member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (before it was formed he had been a member in the Society of Hungarian Scientists), county judge, a landowner farmer, an agricultural writer. He had sold his estate in Debrecen and moved to Földes in 1854, where he rented a plot next to his grandson. His last writings include the agricultural experiences gained in Földes.[48]

- Géza Csáth (1887–1919) He was a writer, physician, psychiatrist and music critic. His writings belonged to the generation of the Nyugat (West). From October 1915 to August 1916, he was working as an assistant regional physician in Földes.[49]

- Lajos Zoltai (1861–1939) He was born in Földes. He was a museologist, archivist, archaeologist, ethnographer, journalist, editor. He was firmly advocating the founding of the city museum of Debrecen, and was appointed to honorary director in 1916. In 1926 the István Tisza University of Debrecen received him as an honorary doctor.[50]

- Lajos Erőss (1857–1911) He was the bishop of the Tiszántúl Reformed Church District, the professor of the Debrecen Reformed Theological Academy and honorary doctor at the University of Geneva. In Földes he had been first, between September 1883 and April 1884, as an assistant pastor beside Gábor Bakoss, then between 1886 and 1893 he was a pastor. During his stay, he was dealing with the history of the village and the church.[51]

- Ferenc Kiss (1862–1948) He was the first rector of the István Tisza University of Debrecen, the teacher of Debrecen Reformed Theological Academy, the founder of the National Reformed Love Association. From 1893 to 1899 he was a pastor in Földes. At the time of his pastor's service, in 1894, the organ of the church was made by József Angster. On his initiative, the village created a memorial garden[28] in front of the church to commemorate the 1896 millennium and this garden is traditionally called the Temple Garden.[52]

- Imre Karacs (1860–1914) He was born in Földes. He learned to sing in Vienna where as a student he sang at the Musikverein and Ehrbar Concert Halls. Between 1886 and 1891 he was an actor in Debrecen. Subsequently, Szabadka and Miskolc followed, then followed by Pozsony, Buda and Temesvár and in 1897, he was again in Debrecen. In the spring of 1907 he left his homeland and went to New York. There he was soon asked to direct the American Hungarian Theater. In the rapidly changing circumstances of Hungarian Theater in New York, Imre Karacs, Árpád Heltai and Lajos Serly were elected most of the times as directors of the theater company. Imre Karacs died on November 29, 1914, in a car accident.[53]

- Zsigmond Karacs (1940-2023) He was born in Földes. His predecessors already lived here in 1692. When he was a few months old, he moved with his parents to Nyíregyháza and then to Nagyvárad. In 1944 they returned to Földes, and in 1951 they went to Budapest. In 1969, he came to Földes again with his own family, in 1972 they moved to Hajdúböszörmény, and finally, from December 1976 until his death, he lived with his family again in Budapest. His interest in family history led him to become a historian of his homeland. Newspapers, magazines, university and other publications preserve his historical, literary, ethnographic, ecclesiastical, family, cultural history, linguistics and other types of studies, nearly two hundred of his writings, most of which are related to Földes. He himself spoke about this: "...I can be anywhere: my daily prayer is Földes. And I'm tormented by the doubt whether I did everything I could."[54]

- Lajos Pércsi (1911–1958). He was born in Földes. After finishing elementary school, he learned blacksmithing. In 1933 he was called in as a soldier. He remained in the army as a soldier and then as a professional, and was sent to Kiskunhalas in 1939 as a sergeant. He also served briefly in the Southland of Hungary, avoiding war captivity in the war. After 1945 he was called back to Kiskunhalas and soon sent to Pest where he graduated from the Kossuth Academy. In the autumn of 1946 he was moved to Pécs, where he graduated from a one-year infantry school. In 1951 he was appointed to the training group leadership of the Ministry of Defense, where he achieved the rank of major. In 1955–1956 he graduated from the Zrínyi Academy. In November 1956, he participated in the revolution with the armed resistance of Schmidt Castle in Óbuda. He became the victim of retribution after the revolution.[55]

- László Kállay (1818–1901) He was a landowner in Földes. His will had been written in 1896 and came into force in 1901. He left almost all of his lands and agricultural buildings to Földes, worth 150,000 Koronas, with the condition that the village was obliged to have a kindergarten operated with a name of Kállay, a refuge house for aged ones, and a foundation. The will was fulfilled conscientiously by the former representative bodies of Földes until 1945.[56]

- Henrik Gál wrestler (1947–) He was born in Földes. He was wrestling between 1960 and 1980. At European Championships in Leningrad (1976) he won gold, in Berlin (1970) silver and in Lausanne bronze medal. He won fourth place in the 1972 Munich, 1976 Montreal Olympics and four World Championships. He won first place in ten national championships. After he had been wrestling for 16 years, he had a successful trainer in his club at the Ferencváros.[57]

- József Pércsi (1942–) He was born in Földes. In wrestling, he won individual championship six times in the Hungarian championship. His nickname was Betyár. In 1971, he won the fifth place in the Sochi World Cup in the 90 kg weight group. He was fourth-placed competitor in the 1976 Montreal Olympics. He was in the team of Budapest Honvéd when the team won the Hungarian championship 11 times.[57]

- Mihály Dresch (1955–) Liszt Ferenc Award Hungarian musician. A saxophone player who based his own music world on the combination of Hungarian folk music and jazz. He was raised in Földes during her childhood.[58]

Sister settlements

[edit]- Marossárpatak (Transylvania)

- Gościeradów (Poland)

Pictures

[edit]-

Reformed Church

-

Village House

-

School and community center

-

School

-

Kindergarten and nursery

-

House of meetings

-

Ornamental garden

References

[edit]- ^ Kálmán Béla: A nevek világa (1989) 143. o. – Béla Kálmán: The world of names (1989) p. 143. Béla Kálmán wrote: "Földes got its name from its non-sandy and non-salty soil." That means: if its soil is not-sandy and non-salty then it is earthy. Earthy means "földes" in Hungarian.

- ^ Földes téves személynévi eredete – False derivation of Földes's name from a personal name.

- ^ A hagyományfenntartó Virágh László tanító – László Virágh, a teacher maintaining tradition. László Virágh taught to the young schoolchildren in the late 1950s that people wandering in the marshy, reedy locations of Sárrét, (Sárrét = muddy meadow) they stopped at this place and told each other: "See, here the place is earthy!"

- ^ Földes története I. (2002) Módy György 22–23. o. ISBN 963-00-9274-3 – History of Földes I (2002) György Módy pp. 22–23. Out of old historians János Karácsonyi did not accept the name Heldus (mentioned in the Váradi Regestrum) as Földes's name. Gábor Herpay accepted his argument and did not link 1215 to Földes. Kabos Kandra accepted the name Heldus as Földes's name. Lajos Zoltai recommended the further consideration of the Heldus word. Today's historians: György Módy, Ilona K. Fábián and Péter Németh accept the Heldus word as the name of Földes.

- ^ The village was not devastated by the Tatars, as the inhabitants had surrounded it with the manure of the animals, then igniting it, Tatars avoided the village because of the smoke.

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) 7. o. – Gábor Herpay: History of Földes Village (1936) p. 7.

- ^ Szentmiklós later Mezőszentmiklós was a village within the border of today's Földes. The first written mention of it had been in 1311 and the final one was in 1688, when the village was finally depopulated.

- ^ Földes története I. (2002) Módy György 37. oldal. ISBN 963-00-9274-3 – History of Földes I (2002) György Módy p. 37.

- ^ Szapolyai János legfelsőbb bírói döntése 1537. V. 7. – Decision of King John Zápolya as a Supreme Justice. They punished one of their noble fellow for one florin on the basis of penalty (vinculum) because he had not paid his contribution to the Tokaj army.

- ^ Földes története I. (2002) Bársony István 50 és 63. oldal. ISBN 963-00-9274-3 – History of Földes I (2002) István Bársony pp. 50–63. In one of the censuses, out of 128 nobles who had one plot in Szabolcs County, 36 lived in the village. According to the census of Pozsony Chamber, 26 (war)tax-payer noble men with one plot lived in the village. That's why the numbers of their houses were not written. They had paid 7 florins, remained debtors with 25 denari.

- ^ Hungarian Queen Izabella promised to István Bajoni that with the death of István Esztári, he could get his legitimate legacy if Várad had come to her possession. Around 1566, the male-side of the Bajoni family also died out.

- ^ Velics Antal: Magyarországi török kincstári defterek I. 1543–1635, Feldes 216–17. o. – Antal Velics: Defters (poll tax lists) of the Turkish Treasury I. 1543–1635, Feldes pp. 216–217.

- ^ Kelenik József: a törökök „…igényt támasztottak olyan falvak, mezővárosok, városok adójára is, amelyekben legfeljebb fogolyként fordult meg török katona." – József Kelenik: the Turks "…demanded taxes from villages and towns where Turkish soldiers turned up only as prisoners."

- ^ "March 6, 1583 Prince István Báthory activated a triple counsel, for the duration of Transylvanian Voivode Zsigmond Báthory's childhood, in the persons of Sándor Kendy, Farkas Kovacsóczy and László Sombori, for the governance of Transylvania." Magyarország Történeti Kronológiája II. kötet 1526–1548 (1983) ISBN 963-05-3183-6 (összkiadás), ISBN 963-05-3315-4 (kötetszám). – Historical Chronology of Hungary II. volume

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) 244. o. – Gábor Herpay: History of Földes Village (1936) p. 244.

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) 46–47. oldal. – Gábor Herpay: The history of Földes village pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b In the Kocsordos part of the border. The Temple of the devastated Mezőszentmiklós village was on this hill.

- ^ Földes és Szabolcs vármegye közös Szabályrendelete 1779. IV. 15. – The jointly made Village Regulation of Földes and Szabolcs County 15th April, 1779.

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) 118. o. – Gábor Herpay: History of Földes Village p. 118. – Election of Lieutenant of the village.

- ^ Első hadnagyválasztás a per után. – Election of the Lieutenant of the village at the first time after the lawsuit.

- ^ Földes története I. (2002) Karacs Zsigmond 147–173. o. ISBN 963-00-9274-3 – History of Földes I (2002) Zsigmond Karacs pp. 147–173.

- ^ Földes története II. (2018) Püski Levente 8-9. o. ISBN 963-00-9275-1 – History of Földes II (2018) Levente Püski pp. 8–9.

- ^ In 1945, food was paid for the last installment of its construction costs.

- ^ Földes története I. (2002) Módy György 16. o. ISBN 963-00-9274-3 – History of Földes I (2002) György Módy p. 16.

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) – Gábor Herpay: History of Földes Village (1936) Pictures of the book and the history of the village.

- ^ Record of Földes's Chief Notary to the Lord-Lieutenant (supremus comes) of Hajdú County on March 19, 1945. (There are 22 soldiers on a remembering plate of German soldiers) Földes története II. (2018) Püski Levente 74. o. ISBN 963-00-9275-1 – History of Földes II (2018) Levente Püski p. 74.

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) 190. o. – Gábor Herpay: The History of Földes Village (1936) p. 190. At this time Földes was Turkish occupation area after the devastating Battle of Mezőkeresztes (1596). Data can be found only about those who moved to Debrecen.

- ^ a b c d Emlékiratok a földesi templom torony- és templomgombjában. Archived 2021-01-29 at the Wayback Machine – Records in the balls of the temple building and temple tower of Földes

- ^ Földes Története I. (2002) Kováts Zoltán 128. o. ISBN 963-00-9274-3 – History of Földes I (2002) Zoltán Kováts p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Magyar Zsidó Lexikon (1929), Szerkesztő: Ujvári Péter, Kiadás: 2000, 284. o. ISBN 963-7475-50-8 – Hungarian Jewish Lexicon (1929). Editor: Péter Ujvári. Edition: 2000. p. 284.

- ^ a b c d Magyar Zsidó Lexikon (1929), Szerkesztő: Ujvári Péter, 284. o. – Hungarian Jewish Lexicon (1929). Editor: Péter Ujvári. p. 284.

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története. (1936) 236. o. – Gábor Herpay: History of Földes Village. (1936) p. 236.

- ^ The Orthodox communities had a principle objection to teachers graduating in the National Israelite Teachers College

- ^ 16 grocers, 6 market-women, 5 feather-gatherers, 4 innkeepers, 3 tailors, 2-2 shoemakers, crop dealers, cattle dealers, egg dealers, 1-1 butcher, baker, steam miller, soda water maker, carpenter, locksmith, chimney sweeper and other professionals.

- ^ Magyar Testgyakorlók Köre – Hungarian Gymnastical Club, one of the most famous soccer clubs in the 1920–30s

- ^ Chevra Kadisa dealt within Orthodox Jewish religious communities with burial ceremonies, keeping the cemeteries in good condition, charity, and care for sick and poor.

- ^ Ó, édes megöletteim, törvénytelen halottaim, utánuk rínak szavaim; Ratkó József 1936–1989 – Oh, my sweet killed ones, my illegitimate dead, after them my words cry; József Ratkó 1936–1989

- ^ Magyar Izraeliták Országos Képviselete – National Representation of Hungarian Israelis. This was the predecessor of the Federation of Jewish Communities in Hungary today.

- ^ Földes története II. (2018) Karacs Zsigmond: A földesi zsidóság 213–228. o. ISBN 963-00-9275-1 – History of Földes II (2018) Zsigmond Karacs: The Jews in Földes pp. 213–228.

- ^ Népszámlálás (2011) Központi Statisztikai Hivatal; Hajdú-Bihar megye; A népesség számának alakulása, terület, népsűrűség; Földes 141. o. – Census (2011); Central Statistics Office; Hajdú-Bihar County; Changes in population, area, population density; Földes p.141.

- ^ Népszámlálás (2011) Központi Statisztikai Hivatal; Hajdú-Bihar megye; Népesség nemzetiség szerint; Földes 159, 162. o. – Census (2011); Central Statistics Office; Hajdú-Bihar County; Population according to nationalities; Földes pp. 159, 162.

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) 129. o. – Gábor Herpay: History of Földes Village (1936) p. 129.

- ^ Kunhalmok a földesi határban – Cuman Mounds in the border of Földes

- ^ Bihari-sík Tanösvény – Bihar Plane Teaching Nature Path

- ^ Bihari-sík Tájvédelmi Körzet – Bihar Plane Landscape Protection District

- ^ Földes története II. (2018) Dr. Dankó Imre: Karácsony Sándor 244–250. o. ISBN 963-00-9275-1 – History of Földes II (2018) Dr. Imre Dankó: Sándor Karácsony pp. 244–250.

- ^ Deme Tamás: Karácsony Sándor természetes rendszeréről (Hozzáférés: 2020. április 4.) – Tamás Deme: On the natural system of Sándor Karácsony Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Földes története II. (2018) Karacs Zsigmond: Balásházy János Földesen 230–239. o. ISBN 963-00-9275-1 – History of Földes II (2018) Zsigmond Karacs: János Balásházy in Földes pp. 230–239.

- ^ Földes története II. (2018) Dr. Bakó Endre: Csáth Géza Földesen 251–256. o. ISBN 963-00-9275-1 – History of Földes II (2018) Dr. Endre Bakó: Géza Csáth in Földes pp. 251–256.

- ^ Földes története II. (2018) Nyakas László – Péter Imre: Zoltai Lajos a polihisztor 241–243. o. ISBN 963-00-9275-1 – History of Földes II (2018) László Nyakas – Imre Péter: Lajos Zoltai the polyhistor pp. 241–243.

- ^ Erőss Lajos Élete és munkássága Hozzáférés: 2020. április 4. – The life and work of Lajos Erőss Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Kiss Ferenc református lelkész, teológus (Hozzáférés: 2020. április 4.) – Ferenc Kiss Reformed pastor, theologian Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Karacs Zsigmond: Karacs Imre és a New York-i hivatásos magyar színészet – Zsigmond Karacs: Imre Karacs and professional Hungarian theatricals in New York

- ^ Karacs Zsigmond élettörténete – The life story of Zsigmond Karacs

- ^ Karacs Zsigmond: Pércsi Lajos élete és halála – Zsigmond Karacs: The Life and Death of Lajos Pércsi

- ^ Herpay Gábor: Földes község története (1936) Kállay László alapítványa 239–240. o. – László Kállay Foundation pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b Lengyel Mihály: Földes sporttörténete (2001) ISBN 963-00-7747-7 – Mihály Lengyel: The sport history of Földes (2001)

- ^ Életút-interjúk: Dresch Mihály (Hozzáférés: 2020. április 4.) – Life Interviews: Mihály Dresch Retrieved 4 April 2020.

External links

[edit] Media related to Földes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Földes at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

![Telek Mound or Temple Hill[17]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/de/Telek-halom_F%C3%B6ldes-10.jpg/150px-Telek-halom_F%C3%B6ldes-10.jpg)