Edward Faragher

Edward Faragher | |

|---|---|

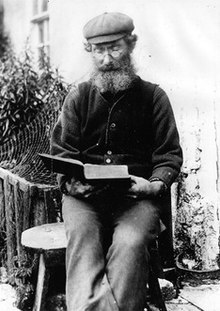

Edward Faragher outside his home in Cregneash | |

| Native name | Ned Beg Hom Ruy |

| Born | 1831 Cregneash, Isle of Man |

| Died | 5 June 1908 (aged 76–77) Blackwell Colliery, near Alfreton, Derbyshire, England |

| Occupation | Fisherman |

| Nationality | Manx |

| Period | Victorian, Edwardian |

| Genre | Poetry, folklore, memoir |

| Subject | Manx legends |

Edward Faragher (1831–1908), also known as (Manx: Ned Beg Hom Ruy),[1] was a Manx language poet, folklorist, and cultural guardian. He is considered to be the last important first language writer of Manx literature and perhaps the most important guardian of Manx culture during a time when it was most under threat. Celticist Charles Roeder wrote that Faragher had "done great services to Manx folklore, and it is due to him that at this late period an immense amount of valuable Manx legends have been preserved, for which indeed the Isle of Man must ever be under gratitude to him."[2]

Youth (1831–1876)

[edit]Faragher was born into a large family of twelve children in Cregneash, a fishing village at the south of the Isle of Man. At this time Manx was the only language spoken in Cregneash, and so his mother stood out as "the only person who could converse with strangers"[2] due to her grasp of English. His father was one of the few people in the village who could write, and so he was called upon to write letters on behalf of other villagers. It was from his father, known as Ned Hom Ruy in Manx, that Faragher's familiar Manx name derives – with the Manx word for "little" being added, making it Ned Beg Hom Ruy ('Little Ned with the Red Beard').[3]

Faragher attended infants' school in Port St Mary followed by the parish school of Kirk Christ Rushen, but his family could not afford for him to attend any longer than two years.[4] The rest of his education came from his parents, or else was self-taught.

At a young age he began earning his living as a fisherman in his father's boat. He was a fisherman for the next seven years; then he moved to Liverpool to work in a safe-making factory.

Faragher enjoyed himself in England, finding that his natural talent at composing verse proved to be popular with young women. In 1899 he would write of this time that:[5]

"[...] when I was living in England, I was putting the young women in a frenzy with my songs. I was often forced to stay at the house on Sunday afternoon because there were so many of them coming after me. And I was serving them all on the same plate. When I would be writing a song to one, she would be reading it to her comrades and they would be all striving to get acquaintance with me, and to get me to do a song for themselves until they were bothering my head."

It was whilst in Liverpool, aged around 26, that Faragher began to write down his verse for the first time, having previously retained it only in his head.[2] Although he enjoyed himself at first in Liverpool, after some years in the city he eventually came to want to return to the Isle of Man. He expressed his feelings in a poem he composed at that time, A poem about things I have seen in Liverpool:[6]

- Farewell to phantasy and art

- That never can fill up my heart,

- And those fair maids, with witching smile,

- No more can my sad heart beguile;

- For still my fancy lingers where

- The youthful Kitty blooms so fair,

- And father tills my native soil

- Among the hills of Mona's Isle.

Fisherman (1876–1889)

[edit]

Faragher returned to Cregneash in around 1876, and earned a living fishing for mackerel at Kinsale and on the west coast of Ireland for the rest of his working life. During this time he encountered rough storms and was even shipwrecked, narrowly surviving.[2] In middle age he married and had children.

Despite the central place of alcohol and heavy drinking in the traditional way of life at that time, upon his return to the island Faragher took up abstinence.[2][4] This started the greatest period of creative output in Faragher's life, as he would go on to write some 4,000 hymns or poems in Manx and English.[7] Also at this time his poetry expanded from the romantic and lyrical to include more contemplative and sacred topics.

Despite his phenomenal output, Faragher's poetry and song received little attention in his own community. Instead they tended to bring him only the "jeers and derision of his uncultured companions and the buxom village belles."[2]

Folk celebrity (1890–1899)

[edit]During the 1880s or 90s Faragher met the Manchester-based German folklorist, Charles Roeder. Roeder recognised the importance of Faragher, particularly as a source of folklore and cultural knowledge, and as a speaker of Manx Gaelic, ranking him as "one of the best vernacular conversationalists extant in the Island."[2] This was especially important at that time as Manx language and culture were in steep decline and in serious danger of dying out completely, due to the dying off of the older generation and the indifference and often even hostility of the youth.

Roeder started up a strong correspondence with Faragher, sending him blank notebooks to fill with folklore "yarns" that he collected before sending them back.[8] A strong friendship developed between them that would last until Faragher's death.

Through Roeder, Faragher became well known in circles concerned with Manx Gaelic culture. He became connected with the major figures of the Manx cultural revival, including Sophia Morrison, John Kneen, Edmund Goodwin and John Clague. As this was at the time of Pan-Celticism, there was also an interest in Faragher from outside the island. Faragher's letters to Roeder tell of visits from gentlemen who had "heard [Faragher's] name mentioned in London,"[9] academics such as the Professor of Gaelic from Scotland who communicated with him through Scottish Gaelic,[9] and Edward Spencer Dodgson (brother of Campbell Dodgson; they were distant cousins of Lewis Carroll) who visited Faragher in Cregneash when visiting the island.[10] In 1896 the foreign interest in Faragher reached such an extent that he would write that he was being "kept busy answering young ladies letters ones that I never saw."[8]

However, the local community grew to resent and even shun Faragher for these visitors and correspondences, as they felt that "he was drawing undue attention both unto himself and the village."[9] This reached such a pitch that Roeder was forced to publish disclaimers in the newspapers to try and cool some of the "aggravation" caused by Faragher's status as folklore informer, mentioning that Faragher was suffering "greatly by the general animus against him."[8]

These social problems that Faragher was suffering at this time were perhaps eclipsed by the serious economic problems that he encountered due to the dire state of the traditional crofting way of life on the island. In the 1890s Faragher began to find it increasingly difficult to make a living as a fisherman and a small-scale farmer. In 1898 Faragher wrote (in his imperfect English) of that year's fishing that, "It has been hard times we could not catch mackerells enough to eat sometimes."[11] By this time Faragher was in his 60s and was beginning to be afflicted by rheumatism, from which he was to suffer increasingly and which threatened to keep him from work entirely.[11] These problems were then compounded by what he saw to be the unfair treatment he received from farmers who kept wages unfairly low. A poem he wrote on this subject features the following stanza:[12]

| Arrane Mychione Eirinee Sayntoilagh / A Song About Covetous Farmers [extract] | |

|---|---|

|

Very little do they give the poor labourer

|

In response to Faragher's struggle to earn enough to live on, Roeder tried to create an interest in him as a literary and cultural figure, so that a public fund might be raised to support him. In 1898 he wrote to the Manx novelist Hall Caine, at that time perhaps the British isles' most popular and successful writer[citation needed], to ask him to write about Faragher so as to raise his profile and the public's awareness of him. However, Caine responded with a letter that reflected the lack of understanding or interest in Faragher at that time:[11]

"I have read the poems with pleasure; but while I think they show a good deal of sensibility & poetic feeling, to certain homely states of emotion, I do not think they are sufficiently remarkable as literature to warrant any special attention. [...] That the author is a man of very amiable character, & that his love of his native island is very tender & beautiful is sufficiently obvious, but I doubt if these are enough to warrant us in claiming for him any attention beyond that which is due to a really admirable man who has preserved a simplicity of natural feeling that is rather too rare."

A public fund was never raised for Faragher, much to the frustration of Roeder and others.

Publishing (1900–1907)

[edit]

Through the instigation and endorsement of Roeder, a small amount of Faragher's writing began to appear in print at the start of the 20th century.

Besides the occasional poem printed in sympathetic newspapers or publications, Faragher's single publication under his own name during his lifetime was his translation into Manx of Aesop's Fables. Faragher had translated other folk tales previously, including Hans Christian Andersen's The Ugly Duckling,[9] but at the instigation of Roeder he completed his translation of all 313 of the Aesop fables in four months in 1901, "while not in the best health, and harassed by domestic afflictions."[2] The publishers, S.K. Broadbent of Douglas, published 25 of these tales under the Manx title, Skeealyn Aesop, in 1901. The intention was to publish further stories in future issues, but there was insufficient interest in the 1901 publication to justify it.[13] Realising the value of the work, despite the lack of interest at that time, Roeder deposited Faragher's full manuscript in the library of the Manx Museum for safekeeping, where it still remains today.[13]

Skeealyn Aesop also included a number of poems and a sketch of old Cregneash. Amongst the poems was Verses Composed at Sea Some Twenty Years Ago, with lines that had perhaps become more pertinent with time:[6]

- Mona, where I have slept,

- Mona, where I have toiled,

- Mona, where I have wept,

- Mona, where I have smiled,

- My native cot, still dear to me,

- I wish to rest in death near thee.

Faragher also published a number of recollections in prose of folk beliefs, stories and traditions. These were printed as "the greater part of"[14] Manx Notes and Queries, Charles Roeder's serialised column in The Isle of Man Examiner, which was at that time "sympathetic to the Manx language revival."[8] The column ran between 21 September 1901 and 24 October 1903, incorporating 87 separate columns, with 261 separately numbered notes.[8] The column ceased due to a lack of collaboration in its production, again despite Roeder's hopes. In 1904, S. K. Broadbent released the column in book form, under the title Manx Notes and Queries. Much to Roeder's chagrin, the book suffered the same fate as Skeealyn Aesop, with poor sales resulting from the lack of interest from the Manx public.[13]

This lack of interest in Faragher and his work at this time extended also to his poetry. Although Mona's Herald and The Cork Eagle published his poetry during his lifetime,[3] they did not publish much, and many publications refused his poetry. One such publication was The Isle of Man Examiner, who refused his poems when sent in by Sophia Morrison.[15] His poetry has been described as "of the homely, descriptive kind, and appeals to the simple emotions of the heart."[2]

Although Roeder and the others of the Manx cultural revival never doubted Faragher's importance, they came to despair of ever rousing sufficient interest in his work during his lifetime. Roeder was to write in a personal letter after Faragher's death that, "he was a very disappointed man & was very shabbily served by the Manx people who ignored him."[13]

Later life (1907–1908)

[edit]By the start of 1907, conditions in Cregneash had become so bad that Faragher's widowed daughter and her two sons were left no option but to emigrate to Canada. Because she had been acting as his housekeeper since his wife had died, Faragher, now aged 76, was forced to leave the island, to live with his son W. A. Faragher, at his house at 56 Blackwell Colliery, near Alfreton in Derbyshire.

Faragher was very sad to leave the island, but he tried to keep up to date with it as best as he could through letters and by reading The Isle of Man Examiner, sent to him each week courtesy of Roeder.[16] He wrote in thanks to Roeder, commenting sadly that "I am not longing for much but a sight of the sea."[8] He composed a lot of poetry whilst first at his son's, until illness overtook him. His son wrote that: "He has been writing verse since he came here until his head got bad, and now he says he shall write no more."[17] One of the most striking poems of this period comments on his sorrow at the decline of Manx culture:

| Vannin Veg Veen / Dear Little Mannin [extract][5] | |

|---|---|

|

Nevertheless, I am saddened for the mother tongue

|

Within 18 months of leaving the island, he had succumbed to a painful illness from which he died between 8 and 10 o'clock on Friday 5 June 1908.[17] He was buried in Derbyshire in an unmarked grave.[18]

In the obituary notice for Faragher in The Manx Quarterly, Roeder wrote that:[2]

"There was no man who loved his Mona so much as he, and every fibre of his heart was intertwined with her traditions and memories of the soil. [...] there was no other Manxman who was so steeped in its lore, and, gifted with a true poetical vein, he sang its beauties and charms. [...] It is entirely due to him that so much traditional folklore has been preserved; he had a fine memory, and his knowledge of things Manx seemed to be inexhaustible, which he would communicate with unreserved readiness and liberality to those who enjoyed his friendship."

Legacy

[edit]In recent years the estimation of Faragher's importance has risen to that given to him by Roeder and others during his lifetime. His poems and prose have been re-printed today and form a part of the canon for Manx language learners. His status as a Manx poet of importance was confirmed in 2010 by his being featured with multiple entries in the 2010 anthology of Manx literature edited by Robert Corteen Carswell, Manannan's Cloak. His house has been incorporated into the Manx National Heritage folk museum at Cregneash. Marking the 100th anniversary of Faragher's death, Yvonne Cresswell, Social History Curator from Manx National Heritage, accurately observed that, "It was, as so often is the case, after his death that the real value and contribution of Ned Beg's work to preserve Manx culture really come to bear."[19]

References

[edit]- ^ Broderick, George (1982). "Manx stories and reminiscences of Ned Beg Hom Ruy". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 38: 117–194.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 'Edward Faragher' (obituary notice) by Charles Roeder in The Manx Quarterly, No. 5, 1908 – available on www.isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/ (accessed 4 October 2013)

- ^ a b 'Note on Edward Faragher' by Basil Megaw in Skeealyn 'sy Ghailck, Isle of Man: Printagraphics Ltd., 1991

- ^ a b 'I have written a little scitch of my life': Edward Faragher's 'A Sketch of Cregneish', Manx Notes 33 (2004), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ a b Mannanan's Cloak: An Anthology of Manx Literature by Robert Corteen Carswell, London: Francis Boutle Publishers, 2010, pp.151–155. (translation by Robert Corteen Carswell)

- ^ a b Skeealyn Aesop by Edward Faragher, Douglas: S.K. Broadbent, 1901

- ^ 'Death of a Manx Poet', obituary in the Isle of Man Times, 13 June 1908

- ^ a b c d e f 'The odium is cast on my old friend Mr Ed. Faragher': Karl Roeder and the Perils of Publication (1902), Manx Notes 30 (2004), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ a b c d 'I am afraid a flail would be too long to send it by post': Edward Faragher writes to G.W. Wood (1899), Manx Notes 110 (2008), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ 'Dr Clague sent me a letter in Manx': Dr John Clague writes to Edward Faragher (1898), Manx Notes 109 (2008), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ a b c 'This true son of the soil': Hall Caine and Edward Faragher (1889), Manx Notes 31 (2004), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ 'I composed some verses about them the other day in Manx': Edward Faragher and his 'Song about Covetous Farmers' (1899), Manx Notes 23 (2004), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ a b c d 'That patronizing Hall Caine—words, words & skinflinty': Karl Roeder writes to Sophia Morrison (1908), Manx Notes 106 (2008), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ 'Introduction' by Stephen Miller, in Skeealyn Cheeil-Chiollee ('Manx Folk Tales') by Charles Roeder, Isle of Man: Chiollagh Books, 1993, ed. Stephen Miller

- ^ 'Both times he was out': Sophia Morrison and Edward Faragher, Manx Notes 39 (2005), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ 'Mr Farquhar is still in the land of the living': Karl Roeder writes to Sophia Morrison (1907), Manx Notes 105 (2008), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ a b 'He is completely worn out': The death of Edward Faragher (1908) (2), Manx Notes 95 (2007), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ 'Mr Farguhar of Cregneish has left the Island permanently': Karl Roeder writes to Sophia Morrison (1907), Manx Notes 104 (2008), edited by Stephen Miller

- ^ 'The Guardian of Manx Culture' on the BBC website (accessed 2 October 2013)

External links

[edit]- Skeealyn Aesop by Edward Faragher, Isle of Man: S.K. Broadbent, 1901 – available from http://manxliterature.com/ (accessed 5 June 2016)

- Skeealyn Cheeil-Chiollee ('Manx Folk Tales') by Charles Roeder, ed. Stephen Miller, Isle of Man: Chiollagh Books, 1993

- Oie'll Vreeshey at Earyween on YouTube; one of Edward Faragher's stories recounted by Ruth Keggin (also available in Manx)

- Oie ayns Baatey-eeastee by Ned Beg Hom Ruy on YouTube one of Edward Faragher's stories read in Manx by Brian Stowell, available on YouTube (accessed 31 September 2013)

- Lines composed on a visit to the grave of Wm.Milner, Esq. an otherwise uncollected poem by Edward Faragher