Draft:Water ballast railway

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by Bearcat (talk | contribs) 2 months ago. (Update) |

A Water ballast railway is a funicular or aerial tramway without a prime mover that uses gravity as its motive power. A synonym for this is water weight cable car.

Construction and drive

[edit]The two carriages of the facility are connected by a rope or cable that runs over a pulley in the mountain station. The carriages maintain approximately balance, so propelling the wagon requires only applying the force to unbalance the system. This is done by artificially increasing the mass of the car standing in the mountain station with water, so that the gravity acting on this additional mass can move the train.

Both cars therefore have a ballast water tank. Between two rides, water is filled into the tank of the carriage in the mountain station, while the tank of the carriage in the valley station is emptied. The upper, heavier vehicle driving down the valley now pulls the lower, lighter one up the incline. The amount of water required depends on the weight difference between the two cars, which is assumed to be around 80 liters for each passenger. Because the length of the rope and thus the weight of the rope between the sheave and the wagon going down the valley increases steadily while the rope is moving uphill, the speed must be regulated while driving. This is done with brakes in the vehicles, which usually act on a rack in the track bed, and especially in longer systems also by draining water from the wagon going down the valley. Some lifts have a lower rope to compensate for the weight of the rope, which is also guided over a pulley in the valley station.

The water required for the operation of the railway was usually taken from a body of water near the mountain station. In places where water from the area was not available at the mountain station, this was pumped from the valley station with pumps through a pressure line running along the route into a reservoir at the mountain station.

The track system is usually single-track and has a passing point in the middle. Due to the special switch construction of the Abtschen Weiche, each car is automatically guided to one of the two sidings. The narrow route reduces the space required and the effort involved in building bridges and tunnels.

Although the water was cheap to come by (unless it had to be pumped up to the mountain station, which required energy to do so), there were disadvantages to operating with water ballast. Winter operation became dangerous as soon as there was a risk of the water tanks or the brake rack icing up. Likewise, the forced break that was necessary until the next trip due to refilling proved to be disadvantageous. In addition, the high operating weight and the high axle load of the wagons increased the maintenance effort for the entire system. Because of these limitations, only a few water-ballast-operated railways were built; and most have been converted to electric operation or have been discontinued.

-

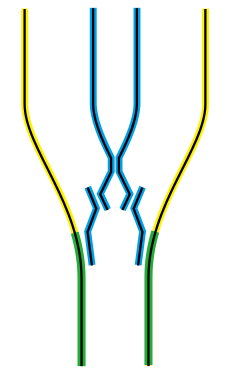

Schematic representation of water ballast railways. Examples of three basic types are: the Malbergbahn in Bad Ems, Germany, – closed (left), the Nerobergbahn in Wiesbaden, Germany (centre) and the Funicular Neuveville–Saint-Pierre in Freiburg, Switzerland (right).

-

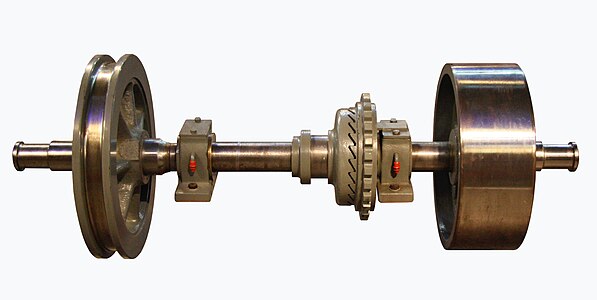

Wheelset of a two-rail funicular with the Abt switch turnout system

-

Nerobergbahn in Wiesbaden (1907)

History

[edit]The oldest facility was probably the Prospect Park Incline Railway opened in 1845 at the Niagara Falls in the United States. The facility was later converted to electric operation and was shut down after an accident in 1908.[1]

The oldest facility in Europe is the Giessbachbahn, which opened in 1879 and was converted to electric operation in 1948. The Bom Jesus do Monte Funicular was opened in Braga (Portugal) in 1882, which is the oldest facility in the world that is still operated with water ballast.

In Germany there is only one railway left with the Nerobergbahn in Wiesbaden. In Switzerland there is only one train left, the Funicular Neuveville–Saint-Pierre in Freiburg.

-

Elevador do Bom Jesus in Braga (Portugal), oldest still operating facility in the world

-

Historical and only water ballast railway still in operation in Switzerland: "Funi" in Freiburg

Railways

[edit](sorted by opening year)

- Bom Jesus do Monte Funicular, Braga, Portugal (in operation since 1882, oldest in the world)

- Saltburn Cliff Lift, Saltburn-by-the-Sea, North Yorkshire, United Kingdom (in operation since 1884)

- Leas Lift in Folkestone, UK (in operation since 1885)

- Nerobergbahn Wiesbaden, Germany (in operation since 1888)

- Lynton and Lynmouth Cliff Railway, Great Britain (in operation since 1890)

- Fribourg funicular (Funi), Freiburg, Switzerland (in operation since 1899)

- Water-balanced cliff railway, Centre for Alternative Technology, Machynlleth, Powys, Wales, United Kingdom (in operation since 1992)

-

cars of the Lynton and Lynmouth Cliff Railway

-

material aerial lift Obermatt–Unter Zingel in the Engelbergertal

Waterballast railways converted to electric operation

[edit]Only a few examples are listed here, as many Railways were first operated with water ballast.

Germany

[edit]- Turmbergbahn, Karlsruhe (opened 1888, converted 1966)

- Heidelberger Bergbahn (Molkenkurbahn) (opened 1890, converted 1907)

Austria

[edit]- Festungsbahn Salzburg (opened 1892, converted 1959)

Switzerland

[edit](complete list of all funiculars in public passenger transport[2])

- Giessbachbahn, Bernese Oberland (opened in 1879, converted in 1912 to drive with Pelton turbine,[3] 1948 to electric drive)

- Chemin de fer funiculaire Territet-Glion (opened 1883, converted 1975)

- Gütsch cable car, Lucerne (opened 1884, converted 1961)

- Marzilibahn, Bern (opened 1885, converted 1973)

- Funicular Lugano–Bahnhof SBB (opened 1886, converted 1955)

- Biel-Magglingen-Bahn (opened 1887, converted 1923)

- Thunersee-Beatenberg-Bahn (opened 1889, converted 1911) →

- Polybahn, Zurich (opened 1889, converted 1897)

- Funiculaire Ecluse–Plan, Neuchâtel (opened 1890, converted 1907)

- Lauterbrunnen–Grütschalp (opened in 1891, converted in 1901, cable car from 2006)

- Rheineck–Walzenhausen mountain railway (opened in 1896, cog railway from 1958)

- Cossonay funicular (opened 1897, converted 1982)

France

[edit]- Funiculaire de Montmartre, Paris (opened 1900, converted 1931)

Czech Republic

[edit]- Letná Funicular, de:Letná-Standseilbahn, Prague (opened 1891, converted 1903)

- Petřín Funicular, Prague (opened 1891, converted 1932)

Waterballast railways converted to rack and pinion railway operation

[edit]- Mühleggbahn, St. Gallen (opened in 1894, converted in 1950, inclined elevator from 1975)

- Rheineck–Walzenhausen cable car (opened in 1896, converted in 1958)

Decommissioned waterballast railways

[edit]Germany

[edit]- Krahnenbergbahn de:Krahnenbergbahn in Andernach am Rhein (opened in 1895, closed in 1941)

- Malbergbahn de:Malbergbahn in Bad Ems (opened in 1887, closed in 1979)

- Funicular Eschberg de:Standseilbahn Eschberg

Switzerland

[edit]

- Gütschbahn in Lucerne, Switzerland (opened 1892, converted 1960, ceased operations 2008, inclined lift since 2015)

- Wartensteinbahn in the canton of St. Gallen, Switzerland (opened in 1892, ceased operations in 1963)

- Chocolate factory Chocolat Suchard in Neuchâtel-Serrières, Switzerland (opened 1892, ceased operations 1954)[4]

- Geneva water ballast railway, Decauville material cable car opened around 1882 to the Bois de la Bâtie, closed

- Funiculaire Lausanne-Signal (opened 1899, closed 1948)

Other countries

[edit]- Funiculaire de Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde in Marseille, France (opened 1892, ceased operations 1967)

- Pokhvalinsky and Kremlyovsky in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia (opened July 15, 1896, ceased operations at the beginning of the 20th century)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Niagara Falls 1907 Incline Railway Crash". Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Hans G. Wägli: Bahnprofil Schweiz 1980. General Secretariat SBB, pp. 71, 73.

- ^ "Giessbach funicular" (PDF). Grand Hotel Giessbach. p. 6.

- ^ "Michel Azéma: Suchard chocolate factory". Funimag, The first web magazine about funiculars.

Literature

[edit]- Walter Hefti: Railways all over the world. Inclined rope levels, funiculars, cableways. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel and others. 1975, ISBN 3-7643-0726-9.

- Hans Waldburger (1979). "The last cable cars with water weight drive". Eisenbahn Amateur. pp. 593–597.

External links

[edit]- Seilbahn-Nostalgie (Website by Claude Gentil, Switzerland)

![Schematic representation of water ballast railways. Examples of three basic types are: the Malbergbahn [de] in Bad Ems, Germany, – closed (left), the Nerobergbahn in Wiesbaden, Germany (centre) and the Funicular Neuveville–Saint-Pierre in Freiburg, Switzerland (right).](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Schema-Wasserballastbahnen.png/426px-Schema-Wasserballastbahnen.png)

![material aerial lift Obermatt–Unter Zingel in the Engelbergertal [de]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b0/Obermatt-zingel1.jpg/163px-Obermatt-zingel1.jpg)