Draft:Signs and symptoms of lupus

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by IntentionallyDense (talk | contribs) 3 seconds ago. (Update) |

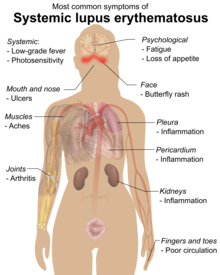

The presentation of lupus varies from person to person.[2] Lupus is considered “the most clinically and serologically diverse autoimmune disease” since it causes a wide range of symptoms that can affect almost any organ.[3] The symptoms of lupus can range from mild to severe.[3] Lupus usually has a pattern of high activity, known as flares, and periods with milder symptoms. The duration and intensity of these flares vary amongst individuals and cannot be predicted.[2] The most common signs and symptoms of lupus are constitutional symptoms such as fatigue, malaise, widespread pain, fever, lack of appetite, and enlarged lymph nodes, however, these symptoms are non-specific and don’t help distinguish lupus from other disorders.[4] Any part of the body can be affected by lupus but it mainly affects the skin, kidneys, joints, nervous system, lungs, muscles, and blood.[5]

Constitutional symptoms

[edit]Constitutional symptoms are extremely common in lupus; however, due to their nonspecific nature, they aren’t part of the classification criteria. The most common constitutional symptom seen in lupus is fatigue; other constitutional symptoms, including fever, enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), enlarged spleen (splenomegaly), and loss of appetite, may also occur.[6]

Fatigue affects up to 80% to 90% of those with lupus and is one of the most debilitating symptoms.[5] Fatigue in lupus is caused by a number of factors such as physical inactivity, sleeping patterns, psychological factors, weight, disease activity, and comorbid disorders.[8][6] Fatigue often continues after treatment of an acute flare and typically gets worse as the day goes on.[5]

Along with fatigue, many people with lupus have brain fog or cognitive dysfunction. Also termed “lupus fog”, brain fog can present as issues with concentration, memory, or thinking clearly. The prevalence of brain fog in lupus is between 3% to 88%.[8]

Although fever is a common symptom of lupus,[8] affecting between 36% and 86% of those with lupus,[5] the prevalence of fever associated with lupus has decreased over the years.[9] This may be due to the increased use and availability of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids[8] or physicians' increased awareness of excluding other potential causes of fevers, such as infections or cancers.[9] Fever is more common in the early stages of lupus[8] and childhood-onset lupus than in late-onset lupus.[9]

The prevalence of lymphadenopathy is thought to be between 5% and 7% at the onset of lupus and between 12% and 15% at any point during the course of lupus. Lymphadenopathy is more prevalent during the initial years of lupus and less frequent as the disease progresses.[10] The lymph nodes in lupus lymphadenopathy are soft, movable, painful, and not fixed to deeper tissues. Lupus primarily affects the lymph nodes in the neck and the lymph nodes under the arms.[8]

Splenomegaly affects 10–45% of those with lupus and is more prevalent when the disease is active. Gross or big splenic enlargement is uncommon; splenomegaly typically occurs in mild to moderate degrees.[11]

Loss of appetite and unexplained weight loss are both symptoms of lupus.[5][12] Weight loss can be due to lupus itself, gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, or complications of lupus.[11][5] Weight loss affects 17% to 51% of those with lupus.[12]

Musculoskeletal symptoms

[edit]The most commonly affected organ system in lupus is the musculoskeletal system.[4] Around 90% of those with lupus experience arthritis.[13] There are three common patterns of arthritis in lupus, joint inflammation without damage to the underlying bone (nonerosive arthritis), erosive arthritis (also called “rhupus”), and Jaccoud’s arthropathy.[14] Alongside arthritis, those with lupus commonly experience joint pain and widespread muscular pain.[15] With lupus, muscle involvement can range from less common inflammatory myopathy or myositis to more prevalentmuscle pain (myalgia).[16]

Lupus arthritis usually affects the smaller joints in the hands,[18] wrists and knees, and is symmetric.[19] Symptoms of lupus arthritis include pain, erythema, swelling, warmth, tenderness, and morning stiffness.[14] Lupus arthritis usually doesn't cause damage to the bones or result in permanent joint deformities.[19][4]

A small portion of those with lupus end up developing erosive arthritis with synovitis, called “rhupus”.[18][20] Those with rhupus fufill criteria for a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.[21][22]

Jaccoud arthropathy is a type of non-erosive and deforming arthritis that can form in some people with lupus.[23] It usually affects the hands but can affect other joints such as the feet and knees.[24] The most common joint deformities caused by Jaccoud arthropathy are swan neck, ulnar deviation, thumb subluxation (z-thumb), hallux valgus, and boutonniere deformity.[25]

Muscle involvement in lupus can range from muscle pain and tenderness to myositis.[26] Muscle pain affects over 50% of those with lupus while inflammatory myositis affects less than 10% of those with lupus.[20][27] Lupus myositis presents similarly to idiopathic inflammatory myopathy and can cause muscle weakness, muscle pain, and elevated muscle enzymes.[28] Rarely, lupus can cause orbital myositis which can cause unilateral or bilateral diplopia or pain.[29]

Avascular necrosis (AVN), also known as osteonecrosis, ischemic necrosis of bone, osteochondriits dissecans, and aseptic necrosis is the death of trabecular bone and bone marrow which can damage the structure of bones.[31] AVN can cause pain and disability[32] or be asymptomatic. AVN affects up to 30% of those with lupus[27] and usually affects the epiphysis of longer bones such as the bones in the hips and knees.[29]

Lupus most commonly affects the tendons by causing tenosynovitis, however, it can also cause tendon dislocation, tendon tear, tendonitis, enthesitis, and tendon thinning.[16] Those with lupus may have a higher risk of localized soft tissue disorders due to deconditioning, fatigue, and weakness. Those with lupus often experience lax connective tissue. 5% to 12% of those with lupus have subcutaneous nodules. Those with lupus are more prone to infections including infections in the musculoskeletal system such as osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, pyomyositis, and soft tissue infections such as necrotizing fasciitis.[29] Osteoporosis is common in lupus and the prevalence ranges from 4.0% to 48.8%. Osteoporosis can lead to a higher risk of fractures.[33]

Mucocutaneous symptoms

[edit]Cutaneous manifestations of lupus are the second most common symptom and occur in 70% to 80% of those with lupus.[34] Those with lupus may experience a wide range of skin symptoms that can vary in severity and duration.[18] In lupus, skin lesions are split into two groups: lupus-specific and lupus-nonspecific manifestations.[35][34]

Lupus-specific skin lesions

[edit]Lupus-specific skin lesions include acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ACLE), subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There is five subtypes of CCLE, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), lupus erythematosus profundus/lupus erythematosus panniculitis (LEP), chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE), tumid lupus erythematosus (lupus tumidus), and verrucous/hypertrophic lupus erythematosus.[27]

ACLE is a type of skin lesion that occurs with lupus. ACLE can be localized or generalized[18] however the localized form is more common.[39] The most common manifestation of ACLE is the “butterfly” or “malar” rash.[40] The malar rash presents as bilateral erythema over the cheeks nose, and occasionally forehead and chin.[41] The malar rash is usually transient, triggered by sun exposure, resolves without scarring,[18] and can last hours to weeks.[42] There may be significant edema, scaling, erosions, and crusts in addition to the initial appearance of smaller erythematous lesions that eventually combine and grow into papules and plaques.[40] ACLE can also cause oral lesions such as ulcers on the hard palate, lips and nose.[43] Generalized ACLE, also known as a “maculopapular” rash, is much rarer.[44] Generalized ACLE frequently affects the palmar and plantar surfaces, the backs of the hands, the extensor surfaces of the fingers,[44] and UV-exposed areas.[39] It manifests as a broad morbilliform or exanthematous eruption made up of several erythematous confluent macules and papules that disperse symmetrically over the entire body.[44] ACLE can cause telangiectasia, periungual erythema, and red lunula. The hair along the hairline may also thin, known as "lupus hair".[39] In rare cases, those with lupus can experience an acute eruption that resembles erythema multiforme major or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Rowell syndrome is the term used to describe erythema multiforme-like lesions found in those with lupus.[42]

SCLE affects 10-15% of those with lupus[45] however it can also be caused by other diseases or induced by medications.[46] SCLE is usually photosensitive and typically affects sun-exposed areas such as the sides of the face, the V of the neck, the trunk and extremities.[41][43] There are two different types of SCLE, annular and psoriasiform or papulosquamous.[46] Ring-shaped erythema, central clearing, polycyclic confluence of the annular lesions, and peripheral collarette scaling at the inner border are the hallmarks of annular SCLE lesions. Vesiculobullous lesions can occasionally form along the edges of annular SCLE lesions. The papulosquamous/psoriasiform form of SCLE exhibits lesions that resemble psoriasis or eczema. Someone with lupus may have both the annular and the papulosquamous/psoriasiform types of SCLE at the same time.[39]

CCLE includes different forms of discoid, verrucous, panniculitis, tumidus, and chilblain lupus;[41] however, localized DLE is the most common type of CCLE.[43] Localized DLE means lesions only develop above the neck, such as on the face, scalp and ears, while generalized DLE causes lesions to develop both above and below the neck.[43][47] DLE lesions can form on one or both sides of the body,[48] and unlike SCLE, lesions can develop in areas that are not exposed to the sun.[45] DLE lesions start as flat or slightly raised, well-defined red spots (macules) or small bumps (papules) with a scaly surface.[43] Over time, the lesions gradually grow outward, forming an active red border with areas of darkened skin. The center of the lesions may develop thinning of the skin, scarring, visible small blood vessels (telangiectasia), and lighter skin colour.[48] In areas like the scalp, eyebrows, and beard, DLE can lead to permanent scarring and irreversible hair loss, known as scarring alopecia.[48] DLE lesions can also develop in and around the mouth. Exposure to the sun and trauma to the skin can trigger or worsen DLE, this reaction is known as the Koebner phenomenon.[48][47] DLE lesions are present in about 15%–25% of people with lupus, but over 95% of those with DLE experience only skin-related symptoms. However, individuals with generalized DLE are at a higher risk of developing systemic organ involvement.[48]

Lupus-nonspecific skin lesions

[edit]Lupus-nonspecific skin lesions can occur with other disorders and are not limited to lupus. Lupus-nonspecific skin lesions are more commonly seen in lupus compared to lupus-specific symptoms and include vasculitis, vascular lesions, livedo reticularis, papular mucinosis, alopecia, and nail changes.[49][35]

References

[edit]- ^ Shiel 2023.

- ^ a b Kyttaris 2024, p. 156.

- ^ a b Kehl & Wallace 2025, p. 413.

- ^ a b c Aranow, Diamond & Mackay 2023, p. 664.

- ^ a b c d e f Rudinskaya, Reyes-Thomas & Lahita 2021, p. 305.

- ^ a b Shaharir & Gordon 2021, p. 351.

- ^ Dey, Parodis & Nikiphorou 2021, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f Kehl & Wallace 2025, p. 417.

- ^ a b c Shaharir & Gordon 2021, p. 353.

- ^ Shaharir & Gordon 2021, p. 355.

- ^ a b Shaharir & Gordon 2021, p. 356.

- ^ a b Kehl & Wallace 2025, p. 418.

- ^ Sandhu, Torralba & Cabling 2025, p. 433.

- ^ a b Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021a, p. 541.

- ^ Kyttaris 2024, p. 159.

- ^ a b Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021b, p. 363.

- ^ Unsal, Arli & Akman 2007, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Kyttaris 2024, p. 157.

- ^ a b Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021b, p. 361.

- ^ a b Rudinskaya, Reyes-Thomas & Lahita 2021, p. 306.

- ^ Antonini et al. 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Sandhu, Torralba & Cabling 2025, p. 434.

- ^ Kyttaris 2024, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021a, p. 543.

- ^ Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021b, p. 362.

- ^ Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021a, p. 544.

- ^ a b c Aranow, Diamond & Mackay 2023, p. 665.

- ^ Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021b, p. 364.

- ^ a b c Sandhu, Torralba & Cabling 2025, p. 436.

- ^ Gurion et al. 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021a, p. 546.

- ^ Barilla-LaBarca et al. 2021b, p. 365.

- ^ Sandhu, Torralba & Cabling 2025, p. 437.

- ^ a b Concha & Werth 2021, p. 447.

- ^ a b Kuhn, Landmann & Bonsmann 2021, p. 372.

- ^ Chiewchengchol et al. 2015, p. 3.

- ^ Mathur, Deo & Raheja 2022, p. 8.

- ^ Uva et al. 2012, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Kuhn, Landmann & Bonsmann 2021, p. 373.

- ^ a b Concha & Werth 2021, p. 455.

- ^ a b c Aranow, Diamond & Mackay 2023, p. 666.

- ^ a b Chong & Werth 2025, p. 422.

- ^ a b c d e Chong & Werth 2025, p. 423.

- ^ a b c Concha & Werth 2021, p. 456.

- ^ a b Rudinskaya, Reyes-Thomas & Lahita 2021, p. 307.

- ^ a b Concha & Werth 2021, p. 454.

- ^ a b Concha & Werth 2021, p. 449.

- ^ a b c d e Kuhn, Landmann & Bonsmann 2021, p. 374.

- ^ Chong & Werth 2025, p. 426.

Works cited

[edit]- Shiel, William C. Jr. (2023-11-08). "Lupus Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, Medications, Prevention". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2024-11-11.

- Kyttaris, Vasileios C. (2024). "Systemic lupus erythematosus". The Rose and Mackay Textbook of Autoimmune Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 149–172. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-23947-2.00016-3. ISBN 978-0-443-23947-2.

- Kehl, Amy; Wallace, Daniel J. (2025). "Overview and clinical presentation". Dubois' Lupus Erythematosus and Related Syndromes. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-93232-5.00039-3. ISBN 978-0-323-93232-5.

- Aranow, Cynthia; Diamond, Betty; Mackay, Meggan (2023). "Systemic Lupus Erythematosus". Clinical Immunology. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7020-8165-1.00052-6. ISBN 978-0-7020-8165-1.

- Rudinskaya, Alla; Reyes-Thomas, Joyce; Lahita, Robert G. (2021). "The clinical presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus and laboratory diagnosis". Lahita's Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-820583-9.00002-6. ISBN 978-0-12-820583-9.

- Shaharir, Syahrul Sazliyana; Gordon, Caroline (2021). "Constitutional symptoms and fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus". Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814551-7.00039-8. ISBN 978-0-12-814551-7.

- Dey, Mrinalini; Parodis, Ioannis; Nikiphorou, Elena (2021-08-13). "Fatigue in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Comparison of Mechanisms, Measures and Management". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (16). MDPI: 3566. doi:10.3390/jcm10163566. ISSN 2077-0383. PMC 8396818. PMID 34441861.

- Sandhu, Vaneet; Torralba, Karina; Cabling, Marven (2025). "The musculoskeletal system and bone metabolism". Dubois' Lupus Erythematosus and Related Syndromes. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-93232-5.00041-1. ISBN 978-0-323-93232-5.

- Barilla-LaBarca, Maria-Louise; Horowitz, Diane; Marder, Galina; Furie, Richard (2021). "Musculoskeletal system: articular disease, myositis, and bone metabolism". Lahita's Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-820583-9.00022-1. ISBN 978-0-12-820583-9.

- Barilla-LaBarca, Maria-Louise; Horowitz, Diane; Marder, Galina; Furie, Richard (2021). "The musculoskeletal system in SLE". Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814551-7.00040-4. ISBN 978-0-12-814551-7.

- Unsal, Erbil; Arli, Ayse Ozgun; Akman, Hakki (2007-05-04). "Rhupus arthropathy as the presenting manifestation in Juvenile SLE: a case report". Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal. 5. Springer: 7. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-5-7. ISSN 1546-0096. PMC 1887527. PMID 17550633.

- Antonini, Luca; Le Mauff, Brigitte; Marcelli, Christian; Aouba, Achille; de Boysson, Hubert (September 2020). "Rhupus: a systematic literature review". Autoimmunity Reviews. 19 (9). Elsevier: 102612. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102612. PMID 32668290.

- Gurion, Reut; Tangpricha, Vin; Yow, Eric; Schanberg, Laura E; McComsey, Grace A; Robinson, Angela Byun (April 2015). "Avascular necrosis in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a brief report and review of the literature". Pediatric Rheumatology. 13 (1). Springer: 13. doi:10.1186/s12969-015-0008-x. ISSN 1546-0096. PMC 4415214. PMID 25902709.

- Concha, Josef Symon S.; Werth, Victoria P. (2021). "Skin". Lahita's Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-820583-9.00008-7. ISBN 978-0-12-820583-9.

- Kuhn, Annegret; Landmann, Aysche; Bonsmann, Gisela (2021). "Cutaneous lupus erythematosus". Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814551-7.00041-6. ISBN 978-0-12-814551-7.

- Chong, Benjamin F.; Werth, Victoria P. (2025). "Skin disease in cutaneous lupus erythematosus". Dubois' Lupus Erythematosus and Related Syndromes. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-93232-5.00040-x. ISBN 978-0-323-93232-5.

- Chiewchengchol, Direkrit; Murphy, Ruth; Edwards, Steven W; Beresford, Michael W (2015). "Mucocutaneous manifestations in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of literature". Pediatric Rheumatology. 13 (1). doi:10.1186/1546-0096-13-1. ISSN 1546-0096. PMC 4292833. PMID 25587243.

- Mathur, Rachita; Deo, Kirti; Raheja, Aishwarya (2022-06-08). "Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in India: A Clinico-Serological Correlation" (PDF). Cureus. doi:10.7759/cureus.25763. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 9270079. PMID 35812543. Retrieved 2025-02-04.

- Uva, Luís; Miguel, Diana; Pinheiro, Catarina; Freitas, João Pedro; Marques Gomes, Manuel; Filipe, Paulo (2012). "Cutaneous Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus". Autoimmune Diseases. 2012: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2012/834291. ISSN 2090-0422. PMC 3410306. PMID 22888407.