Draft:Reign of Amadeo I of Spain

| Review waiting, please be patient.

This may take 2 months or more, since drafts are reviewed in no specific order. There are 2,107 pending submissions waiting for review.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Reviewer tools

|

| Reino de España | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1871–1873 | |||||||||

Spanish possessions around the world between 1821 and 1898. | |||||||||

| Anthem | |||||||||

| Marcha Real | |||||||||

| Capital | Madrid | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||

| • Motto | Plus Ultra (latin): Further beyond | ||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes | ||||||||

| Historical era | Contemporary history of Spain | ||||||||

| 2 January 1871 | |||||||||

| 10 February 1873 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The reign of Amadeo I marked the first attempt in Spain's history to implement the system of parliamentary monarchy ("popular monarchy" or "democratic monarchy," as it was referred to at the time). However, it ended in failure, lasting only two years—from January 2, 1871, when Amadeo I was proclaimed king by the Constituent Cortes, to February 10, 1873, when he submitted his abdication.

One of the main reasons attributed to this failure was the death of General Prim on the very day the new king arrived in Spain, following an attack three days earlier. Prim, apart from being the principal supporter of the new monarch, was the leader of the Progressive Party, the most significant political force within the monarchist-democratic coalition. His death sparked a succession struggle between Práxedes Mateo Sagasta and Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, which ultimately led to the "traumatic disintegration" of the coalition that was intended to sustain the Amadeist monarchy.[1] As historian Mª Victoria López-Cordón noted, "the defection of the [forces] that should have supported it made the experiment impossible."[2] Furthermore, Amadeo I's monarchy failed to integrate opposing political groups that did not recognize the new king's legitimacy and continued to advocate for their own political projects—whether the Republic, the Carlist monarchy, or the Alfonsist monarchy.

The reign of Amadeo I forms part of the period known as the Democratic Sexennium (1868–1874), which began with the Revolution of 1868 and concluded with the equally unsuccessful First Spanish Republic (1873–1874).

Election of Amadeo of Savoy as King of Spain

[edit]

Finding a king became a serious internal problem— the political forces that had overthrown Isabel II could not agree on who should replace her: the Duke of Montpensier, the unionists; Fernando of Saxony-Coburg, the progressives—[3] and it was also an international issue, as rivalries between the major European powers (all monarchies) erupted as each sought to place "their" candidate on the vacant Spanish throne. The Spanish government announced the candidacy of the Prussian Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, but soon encountered opposition from Napoleon III, who, in the midst of a rivalry with Prussia, saw the fact that two border territories with France would be led by members of the same royal house as a near threat. This rivalry even provided the pretext for the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 [which resulted in the Prussian victory, the dethroning of Napoleon III, and the proclamation of the Third French Republic]. Napoleon III also opposed the candidacy of Antonio of Orleans, Duke of Montpensier, due to the antagonism between the French royal houses [the Bonaparts and the Orléans]; additionally, Montpensier’s family connection to the Bourbons (he was the brother-in-law of the deposed Isabel II) made this option unpopular among Spanish monarchist-democratic parties. Only the Italian Savoy candidacy remained, promoted by Prim from the summer of 1870, becoming his main supporter.[4]

On November 16, 1870, the Constituent Cortes elected the Duke of Aosta, second son of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, as the new King of Spain, under the name of Amadeo I. The vote was 191 in favor, 100 against, and 19 abstentions—60 voted for the federal republic, 27 for the Duke of Montpensier, and 8 for General Espartero.[5] "The solution satisfied only the progressives and was accepted with great coldness by Spanish public opinion, which never felt any enthusiasm for the Italian prince."[6] Father Luis Coloma, in his famous novel Pequeñeces..., referred to a "grotesque satire" titled "The Prince Lila," held in the gardens of Retiro in Madrid, "where they called the reigning monarch by the name of Macarroni I," "while a vast crowd of all colors and shades applauded."[7]

First year

[edit]

The reign of Amadeo I "could not have begun under worse omens." Shortly after disembarking in Spain on December 30, 1870, he was informed that General Prim, his primary supporter, had died as a result of an attack that occurred in Madrid three days earlier as he was traveling from the Congress to his residence. This event deprived Amadeo I of indispensable support, particularly in the critical early days, and proved decisive considering that the progressive faction ultimately split between Prim’s two successors, Práxedes Mateo Sagasta and Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla.[8]

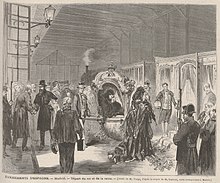

The new king entered Madrid on January 2, 1871, and that same day he swore allegiance to the 1869 Constitution before the Cortes.[9] Later, he visited the Church of the Virgin of Atocha, where General Prim’s funeral chapel had been set up—a moment immortalized by the painter Antonio Gisbert.[10]

Government of General Serrano: The Failure of "Conciliation"

[edit]Following the assassination of General Prim, a "conciliation" government was formed under Admiral Topete at Prim's deathbed request.[10] In line with this approach, Amadeo I proposed to the Cortes that General Serrano, a unionist who had served as regent from the promulgation of the 1869 Constitution until the new king's oath, be appointed as the new President of the Council of Ministers to form a government of "conciliation." Serrano followed the king's instructions and assembled a cabinet including leaders from all factions of the monarchist-democratic coalition supporting the new monarchy: the progressives Sagasta, who became Minister of the Interior, and Ruiz Zorrilla, Minister of Public Works; the monarchist democrat or "cimbrios" Cristino Martos; and the unionist Adelardo López de Ayala, in the Ministry of Overseas Territories.[11][12]

The first task of Serrano's government, which some members viewed as "transitional," was to prepare for the first elections under the new monarchy, aiming to secure a comfortable majority for the governing coalition. To this end, an electoral law was enacted that reverted to the old moderate system of district-based voting, replacing the provincial constituencies previously championed by the progressives and used in the 1869 constituent elections. This change allowed the government to more easily exert its "moral influence" in rural districts. The objective of achieving a clear majority was accomplished, although "the opposition [composed of Carlists and federal republicans] secured a significant number of deputies, whose weight in the Cortes was magnified by the weakness of the governing coalition."[13]

The governing coalition won 235 seats—approximately 130 progressives, over 80 "borderline" or "Aostist" unionists, and about 20 monarchist democrats. The republicans secured 52 seats, the Carlists 51, and the moderates 18. Meanwhile, dissident unionists under Ríos Rosas, who continued to support the candidacy of the Duke of Montpensier, and Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, who advocated for the rights of Prince Alfonso of Bourbon, son of the deposed Queen Isabella II, won seven and nine seats, respectively.[14]

When Serrano's government and the Cortes began addressing the legislative development of the democratic principles enshrined in the 1869 Constitution—such as the establishment of juries or the separation of church and state—or tackling pressing issues (the abolition of military conscription; the war and abolition of slavery in Cuba; social unrest among laborers and workers, among others), tensions emerged. "The borderline unionists and Sagastan progressives believed that, with the Constitution crowned by the Savoy dynasty, policies should aim to preserve the existing order. In contrast, the democrats and progressives aligned with Ruiz Zorrilla argued that consolidating these achievements required the immediate implementation of a program of social, economic, and political reforms."[15]

Thus, the conflict between Sagasta and Ruiz Zorrilla stemmed from their differing views on how to secure the new parliamentary monarchy. Sagasta, adhering to policies likely championed by General Prim, advocated conciliation with General Serrano's unionists, who were to form the dynastic right (the conservative party), while Sagasta himself, as leader of the Progressive Party, would lead the dynastic left (the liberal party). Sagasta also supported an uncompromising stance against regime opponents, namely the Carlists and federal republicans. In contrast, Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla championed maintaining the alliance between progressives and monarchist democrats ("cimbrios") through an advanced reformist agenda that ultimately sought to integrate republicans into the new parliamentary monarchy by demonstrating that their goals could also be achieved within its framework. Sagasta, however, saw this approach as placing the monarchy in the hands of its enemies and distrusted Ruiz Zorrilla's commitment to the regime. As such, Sagasta outright rejected parliamentary collaboration with republicans, which Ruiz Zorrilla defended.[16]

Opposition to the Monarchy of Amadeo I

[edit]The high nobility and the ecclesiastical hierarchy did not recognise the new Amadeuist monarchy. In principle because it was the institutionalisation of the Revolution of 1868, which had put an end to the Elizabethan Monarchy in which they enjoyed a privileged position, and because they feared that the new power would put an end to them or that it would be the prelude to republicans and ‘socialists’ who were opposed to property and the confessional state. The high nobility adopted a casticist stance, claiming to defend supposedly national values against the ‘foreign king’, which translated into a boycott of the court and continual snubs to the person of King Amadeo, to whom they made no secret of their loyalty to the dethroned Bourbons.[17] The best-known episode was the so-called ‘Rebellion of the Mantillas’, recounted by Father Luis Coloma in his well-known novel Pequeñeces...:[18]

They, with their boasts of Spanishism and their aristocratic rampages, had succeeded in creating a vacuum around Don Amadeo of Savoy and Queen María Victoria, cornering them in the Palacio de Oriente, in the midst of a court of ‘furrile capes and well-to-do shopkeepers’, according to the opinion of the Duchess of Bara; of ‘indecent’, added Leopoldina Pastor, who were not even indecent. The ladies came to the Fuente Castellana, lying in their carts, with classic lace mantillas and tile combs, and the fleur-de-lis, the emblem of the Restoration, shone in all the headdresses worn in theatres and parties.

For its part, the ecclesiastical hierarchy saw in King Amadeo the son of King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, who had ‘stripped’ Pope Pius IX of the Papal States; it was also opposed to freedom of worship and other measures that could culminate in the complete separation of Church and State.[17] And it should be borne in mind that ‘the hierarchy, invested with the intolerant and combative spirit that the Syllabus had given it, exercised a notorious influence not only on the middle classes, the majority of whom were Catholic, but also in the rural world, where the parish priest was often the interpreter of events that came from outside’.[7]

Amadeo I tried to fill the vacuum of the ‘old nobility’ by ennobling members of the industrial and financial bourgeoisie who did support the new democratic monarchy, although there were also desertions in this social group, especially from the sector most closely linked to the Cuban issue, due to the radical governments' plans to abolish slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico,[19] and from the Catalan industrial bourgeoisie who opposed the free trade system set in motion in 1869 and which the Radicals continued to defend.[19] The Catalan industrial bourgeoisie, which had been opposed to free trade since 1869 and which the Radicals continued to defend, also deserted the new monarchy.[20]

The Carlists, who had experienced an unprecedented boom since 1868, extending their influence beyond their traditional fiefdoms in the Basque Country, the interior of Catalonia and the north of Valencia, claimed the traditional monarchy, embodied in the figure of the pretender Carlos VII (grandson of Carlos María Isidro of the First Carlist War). At first the ‘neo-Catholic’ sector, headed by Cándido Nocedal, carried more weight, advocating the ‘legal route’, i.e., to achieve great influence in the Cortes through the elections, even presenting itself in coalition with the Republicans in the first elections to the ordinary Cortes and achieving a good result with 51 deputies and 21 senators.[19] ‘The election of Amadeo I irritated them deeply and from that moment on only the influence that Nocedal and the legalist wing exercised over Don Carlos was able to contain premature uprisings. [...] In September 1871, Don Carlos, perhaps against his own wishes, had to restrain his supporters once more."[21]

The Republicans were opposed to any kind of monarchy and continued to advocate the Federal Republic, something they saw within their grasp after the fall of the Second Empire in France. But in the Federal Republican Party, different political projects coexisted under ‘the mythical mantle of the Republic’, ranging from the staunch defenders of the right to property to ‘socialists’, and from those who advocated the ‘unitary’ republic —a very minority sector— to those who defended the Federal State on the model of the United States and Switzerland, who constituted the majority sector, with Francisco Pi y Margall and Nicolás Salmerón at its head. Also, as in Carlism, there was opposition between the supporters of the ‘legal road’, who did not refuse to collaborate with the radicals of Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, and those who opted for the ‘insurrectional road’.[22]

First government of Ruiz Zorrilla: division of the progressives

[edit]On 15 July 1871 the ‘radical’ democrat and progressive ministers Martos, Ruiz Zorrilla, Beránger and Moret resigned in order to put an end to Serrano's ‘conciliation’ government, to make way for the ‘demarcation of the camps’ between conservatives and radicals in the government coalition and to form a homogeneous government. The king, who was still in favour of ‘conciliation’, had no choice but to appoint Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla as the new president of the government on 24 July. ‘This solution meant the defeat of the Unionists, but also the defeat of Sagasta and his followers in their plan to maintain the union as long as the new regime was in danger."[23]

At first Ruiz Zorrilla tried to get Sagasta's progressives into his government, but the latter refused because, as he explained in Congress, the regime could not be saved by an ‘exclusive party’ policy.[24] Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla then formed a government with only the progressives of his faction and the democrats, in which he himself assumed the Interior portfolio, with Eugenio Montero Ríos in Grace and Justice, General Fernando Fernández de Córdova in War, Servando Ruiz Gómez in Finance, Santiago Diego-Madrazo in Public Works, Tomás María Mosquera in Overseas, and Vice-Admiral José María Beránger in the Navy. Cristino Martos did not accept the Ministry of State and did not form part of the government, which presented its programme to the Cortes on 25 July and whose motto was ‘liberty, morality, civility.’[25]

The democrats succeeded in getting Ruiz Zorrilla to appoint Salustiano Olózaga, president of the Congress of Deputies, as ambassador to Paris, and then to present the democrat leader Nicolás María Rivero to fill the vacant post. Faced with this manoeuvre, the ‘Sagastinos’ progressives proposed Sagasta himself for the post, in an attempt to prevent a prominent member of the group of democrats, whom they considered closer to the Republic than to the Monarchy, from occupying it. Ruiz Zorrilla and Sagasta met on 1 and 2 October 1871 to avoid the break-up of the progressive party, but Sagasta's offer to withdraw the two candidates and agree on a consensus candidate was rejected by Ruiz Zorrilla because it would mean that the democrats would join the republicans, putting an end to his ‘radical’ reformist project to consolidate the monarchy. During this conversation Sagasta said to Ruiz Zorrilla:[26]

Given the alternative of eliminating the [[Cimbri|cimbrios]] —the democrats— or dividing the Progressive Party, a part of which wants its creed to prevail and be faithfully executed, you have not hesitated, you stay with the cimbrios and break with your long-standing friends; the consequences will be dire for everyone, but the fault is not mine.

In the vote for the presidency of Congress held on 3 October, Sagasta beat Rivero by 123 votes to 113 —there were only two blank votes— and Ruiz Zorrilla, who saw the result as a vote of no confidence in the government, then resigned.

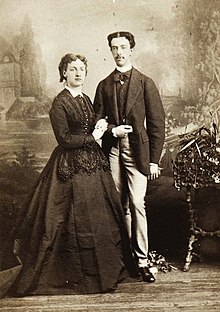

King Amadeo I had just returned from a trip he had made to several provinces in eastern Spain with his wife, which had been organised by the government to boost his popularity and during which he had passed through Logroño to visit General Espartero —who was retired but still enjoyed enormous popularity among the progressive liberals who regarded him as their ‘patriarch’— and who assured him of his loyalty because he had been elected by the ‘national will’. When Amadeo I met Ruiz Zorrilla he asked him to dissolve the Cortes and call new elections, which the king refused to do because he saw no constitutional or parliamentary reason to do so —he had not lost the parliamentary majority that supported him and there had been no formal vote of censure against him—. This assessment was confirmed when he met with Sagasta, who assured him that he and his followers continued to support the programme the government had presented on 25 July, and he asked the king to make Ruiz Zorrilla see reason so that he would continue to head the Council of Ministers.[27]

Malcampo government: the failure of the reunification of the Progressives

[edit]

As Ruiz Zorrilla did not change his mind, then the king, after receiving General Espartero's refusal to preside over the new government on the grounds of his advanced age, entrusted the formation of the government to Sagasta, but the latter proposed, so as not to appear to be opposing Ruiz Zorrilla, that he should appoint another progressive from his group in his place, Counter-Admiral José Malcampo —a sailor who had accompanied Vice-Admiral Topete in the Revolution of 1868, ‘which gave him revolutionary prestige and authority, and it was thought difficult that he could be described as a “reactionary” by the radicals, an innocent presumption in which they failed’—.[28] His government served as a bridge to the one finally headed by Sagasta himself on 21 December 1871,[29] but the Progressive Party, the main political force underpinning the Monarchy of Amadeo I, had broken in two: a more conservative sector, close to the approaches of the Liberal Union headed by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, and a more advanced one headed by Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla, which called itself the ‘democratic progressive’ or Radical Party and which included the monarchist democrats or ‘[[cimbri|cimbrios]]’ led by Cristino Martos and Nicolás María Rivero.[30]

The progressive sector led by Sagasta did not abandon the idea of achieving the reunification of the Progressive Party, but on the basis of its ‘historical’ programme, which placed national sovereignty before individual rights, which could be regulated by the Cortes to ensure compatibility between liberty and order, while the democrats and the ‘Zorrillists’ defended the illegitimacy of these rights and that any excesses in their use should be dealt with by the courts of justice. Thus, what Sagasta was asking of Ruiz Zorrilla was that he abandon his alliance with the democrats or that the latter accept the superiority of the principle of national sovereignty. That is why Sagasta understood Malcampo's government as a ‘transitional ministry’ awaiting progressive reunification, and that is also why the cabinet ministers were exclusively progressive —no member of the Liberal Union was included— and the government programme presented to the Cortes by the new president was the same as the one Ruiz Zorrilla had proposed on 25 July.[31]

However, the first response of the ‘Zorrillists’ was to unilaterally proclaim their leader as ‘active head of the democratic Progressive Party’, recognising General Espartero as its ‘passive head’ —Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla remained convinced that ‘with economic and social reforms, he would bring the democratic monarchy closer to the people, distancing it from federalism and socialism, and would cause republican benevolence to be transformed into fusion in the liberal party in the near future’—.[32] Faced with this initiative, Sagasta's progressives formed their own Board of Directors of the Democratic Progressive Party on 20 October, thus formalising the break-up of the party. Attempts by some groups and progressive personalities such as Ángel Fernández de los Ríos to rebuild party unity failed —the appeal to old leaders such as Salustiano Olózaga or General Espartero did not work either because both of them opted for Sagasta's sector—.[31]

Debate in the Spanish Parliament on the illegalisation of the Spanish section of the IWA.

[edit]

An opportunity for reunification arose when the Malcampo government, anxious to show the country that democratic monarchy was not synonymous with disorder or ‘tame anarchy’, proposed to the Cortes that they vote to outlaw the Spanish section of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA) which had been founded in June the previous year at a congress in Barcelona, considering it outside the Constitution. The underlying reason was the enormous repercussions of the workers' insurrection of the Paris Commune of March-May 1871, which had spread fear of “socialism” among the propertied classes throughout Europe —indeed, when on the May 2 holiday the internationalists attempted to hold a banquet of fraternity between Spanish and French, it was broken up by the “truncheon party”, “which the government used to push violence beyond the limits set by law”—.[33][34]

Serrano's Unionists and the Progressives of Sagasta's sector, who supported the government, were in favour of illegalisation, a position which was also supported by the Carlist deputies because they considered the internationalists the ‘enemies of society’, while the Republicans were against it. The Republicans were against it because they defended the inalienable freedom of association and saw the measure as the work of ‘reaction’. The problem arose within Ruiz Zorrilla's group because, on the one hand, they agreed with the Republicans that the right of association should prevail, but on the other hand they did not want to be seen by the middle classes and conservatives, and even by the king himself, as defenders of the ‘disorder’ which the internationalists personified and which had manifested itself in the Paris Commune. The final solution adopted by Ruiz Zorrilla was not to support Malcampo's government, but neither did he support the Republicans, and so he opted to abstain, thus losing a last chance for the reunification of the progressives. For historian Jorge Vilches, this moment was decisive because the vote in favour of the government ‘would have made possible the conversion of the Progressives into the Liberal party that would take turns with the Unionists transformed into the Constitutional Conservatives. This party system could have provided greater stability than the one [Ruiz Zorrilla] was aiming for, and therefore successfully completed the attempt to establish a constitutional monarchy in Spain that would ensure freedom and order’. On 10 November 1871 a vote was taken in the Cortes, in which 192 deputies —Unionists, ‘Sagastino’ Progressives and Carlists— spoke in favour of banning the IWA and 38 votes against this cause —the federal republicans—.[35]

However, the ban on the IWA, which had been voted in the Cortes, was not enforced due to the intervention of the Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, who insisted that the Constitution of 1869 protected the IWA by recognising the right of association. Thus, the Spanish section of the IWA was able to continue its activities and managed to spread outside Catalonia, especially among the day labourers of Andalusia and the workers and artisans of Valencia and Murcia, holding its second congress in Saragossa in April 1872, where the Bakuninist theses prevailed, which were confirmed at the Cordoba congress held between 25 December 1872 and 3 January 1873.[36]

Vote of no confidence in the government and suspension of the Cortes

[edit]On 13 November, just three days after their defeat in the vote to outlaw the IWA, Ruiz Zorrilla's radicals tabled a vote of no confidence against the Malcampo government, which a 'Zorrillist' newspaper described as a 'pirate ministry' for its embezzlement. The ultimate reason for the decision was that they wanted access to the government before Malcampo's government could call elections and obtain a majority in Congress, as the four-month period between elections was about to expire. Sensing an opportunity, the Carlists tabled a motion on religious associations, hoping that the Republicans and Radicals would join them and bring down the government. When the votes on 17 November showed that the government was a minority in the Cortes, with only the support of Sagasta's 'historical' progressives and the 'unionists', who had 127 deputies against the 166 of the Carlists, Radicals and Republicans, the government obtained the decree from the king suspending the Cortes and Malcampo was not forced to resign. The King explained to his father [the King of Italy] that he had signed the decree because of the scandal caused by the union of the Radicals and the Anti-Dynastics [Carlists and Republicans]. When the session was adjourned, the federalists shouted: 'Long live the Republic! Some radicals went so far as to describe the king's decision, while acknowledging that it was constitutional, as a 'coup d'état'.[37]

Municipal elections

[edit]The Radicals continued their frontal opposition to the government, and in the municipal elections of 9 December they again joined forces with the anti-dynastic parties, this time only with the Federal Republican Party. The results of the elections, in which there was a high abstention rate of between 40 and 50 per cent, were highly controversial, with all parties claiming victory. The 'zorrillist' newspaper El Imparcial claimed that the government had been defeated because, of the 600 important municipalities, only 200 had been won by the ministerialists, while the other 400 had been won by the government's opponents —250 by the Radicals, 180 by the Republicans and 50 by the Carlists—. On the other hand, if only the provincial capitals were counted, the result was favourable to the government, as the Minister of the Interior hastened to inform the King, since the government candidates had won in 25, including Barcelona, Seville, Cádiz and Malaga, while the opponents had won in 22, of which the Radicals had won only 3, although one was Madrid, while the Republicans had won 14, including Valencia, La Coruña and Granada, and the Carlists 5. The King therefore refused Ruiz Zorrilla's request to hand over power to him on the grounds that the government had been defeated in the elections.[38]

End of the Malcampo government and appointment of Sagasta

[edit]After the municipal elections, the King gave the government one week to reconvene the Cortes, knowing that if it failed to do so it would be forced to resign. He therefore assured the political leaders that his successor, who would receive the decree to dissolve the Cortes and call new elections, would be the one with the 'maggior numero di voti dinastici' [the one with the highest number of votes of the dynastic parties], thus invalidating the manoeuvres of the Radicals, Republicans and Carlists to add their deputies in order to bring down the government. Finally, Malcampo, who had seen no point in continuing his government since 17 November as the possibility of reuniting the Progressive Party became increasingly remote, resigned on 19 December in anticipation of the reopening of the Cortes. The man appointed to replace him was Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, in accordance with the parliamentary practice that when a head of government resigns without constitutional cause or loss of majority, the President of Congress should replace him. Sagasta formed his government two days later.[39]

Second year

[edit]"If in 1871 there had been a succession of government crises, in 1872 the persistence of the same crises led to a progressive deterioration of political and parliamentary life. A political imbalance with disastrous consequences for the monarchy of Amadeo I."[40]

Sagasta's government: the constitutional conservatives in power

[edit]

At first, Sagasta offered Ruiz Zorrilla's Radicals a broad participation in his government —four portfolios, half of the cabinet— but they rejected the offer because it would mean separating from the Democrats and breaking the benevolent pact with the Republicans —in the meeting between Sagasta and Ruiz Zorrilla, the latter replied that he was more than a progressive, he was a radical—. Sagasta was then forced to seek an alliance with General Serrano's Unionists, who joined his government, albeit with only one portfolio, that of the overseas territories, held by Admiral Topete. The rest were "historical" progressives, including the previous head of government, Counter Admiral José Malcampo, who held the portfolios of War and the Navy: Bonifacio de Blas, Santiago de Angulo, Francisco de Paula Angulo and Alonso Colmenares.[41]

Presenting the new government to the Cortes on 22 January 1872, Sagasta defined it as progressive-conservative, as he wished to maintain the rights of the Constitution while at the same time fulfilling the duties inherent in it. After defending the monarchy "as the essential foundation of public liberties", he concluded by proposing a system of loyal and benevolent parties, without extreme or exclusionary policies, but conciliatory, "more progressive the one, less progressive the other; but liberal conservative the one and liberal conservative the other". The government was defeated in the vote, but since there were more dynastic votes for it than against, the King kept his word and granted Sagasta the decree to dissolve the Cortes so that he could call new elections to secure a solid majority in the Chamber that would allow him to govern. Ruiz Zorrilla's response can be summed up in the slogan 'Radicals defend yourselves' and the exclamation 'God save the country! God save the dynasty! God save freedom! The Republicans went much further, claiming that 'the King has broken with Parliament, that today the Savoy dynasty comes to an end'.[42]

The Radicals attributed the King's decision to the existence of an alleged 'camarilla' at Court which, as in the time of Isabella II, was plotting to prevent them from gaining access to power. According to them, it was made up of the monarch's Italian advisers, Dragonetti and Ronchi, the conservatives who visited the king, and the 'neo-Catholics' who influenced the very Catholic Queen Maria Victoria. Thus, the day after Sagasta was confirmed as head of the government, Ruiz Zorrilla criticised the king's decision in the Cortes and pleaded for the 'right to revolt' because he believed that freedoms were under threat. "Amadeo I was no longer untouchable for the radical newspapers.... Such was the discontent that all the radical leaders invited to the palace on Fridays, with the exception of Moret, began to stay away from the customary lunch given by the King at the palace, claiming indisposition". At an election rally in Madrid on 2 February, José Echegaray said that the windows of the Palacio de Oriente had to be opened so that the air of freedom could be breathed in, and a leading article in El Imparcial on 22 February stated that the Radical Party 'continues to be despised [by the King], as it has always been despised', thus equating the monarchies of Amadeo I and Isabella II. Sagasta's government was described as a 'reactionary ministry'.[43]

In January 1872, in a letter to his father, the radical Francisco Salmerón, one of the 'noble' progressives who had most defended the alliance of the Progressive Party with the [[Cimbri|cimbrios]] democrats, he said

The palace is not hostile, for the king delights in courtesans; and the queen in neo-politics. The infamous Sagasta is waging an implacable war against the Radicals; and the pseudo-conservative villains are taking advantage of his rage to absorb him and fascinate the King in order to sink him. We, the Radicals, go into the electoral struggle with the proof of defeat; then, in retreat, we shall witness the catastrophe prepared by the iniquities of the Government, the ingratitude of the Monarch, the perfidies of the Unionists and the furious Sagasites. At last the light will come; what I do not know is who will be left behind in the flood.

Birth of the Constitutional Party and the 'National Coalition'

[edit]

To prepare for the elections, Sagasta's Progressives and Unionists formed a joint election committee which published a manifesto on 22 January, summarising the government's programme. The Unionists saw this as the first step towards the formation of a single party, but Sagasta resisted because he intended to form a 'third party' between Unionists and Radicals that would attract 'the best of both sides', thus keeping alive the idea of reuniting Progressivism. The King intervened and, in order to be understood as he did not speak Spanish well, he asked the Unionist José Luis Albareda, who regularly visited the King, to write him a "little piece of paper" in which he advocated the formation of a Conservative Party which would alternate with the Radical Party in power if the electorate so decided. In this way he closed the door to the 'third party' and Sagasta, who had initially resigned when he felt disowned by the King, was forced to accept the merger when the King threatened to hand power to the Radicals. Thus, on 21 February 1872, the new party was born, called the Constitutional Party because its aim was to defend the dynasty and the Constitution, and the government was immediately reshuffled to include four progressives and three unionists in addition to Sagasta. The slogan of the new Constitutional Party in the elections of 2 April was "Liberty, the Constitution of 1869, the dynasty of Amadeo I and the integrity of the territory".[44]

For its part, the Radical Party, in its eagerness to overthrow the government, extended the 'national coalition' it had formed with the Republicans for the municipal elections of December 1871 to include the other anti-system party, the Carlists, with the common aim, without any of the three parties abandoning their principles, of 'defeating the government, the fruit of immorality and lies', because 'freedom and the honour of the fatherland... are above all'. Later, the Moderate Party of Alphonsine also joined the coalition. During the electoral campaign, patriotic rhetoric was used, such as 'free and independent Spain' in reference to the King's Italian origins, or the argument used by the Republican Emilio Castelar to convince his party colleagues to support the 'National Coalition', claiming that it was formed to 'defend the government of Spain for the Spaniards', which became the slogan 'Spain for the Spaniards' in the Republican election manifesto of 29 March. The parties in the 'National Coalition' pledged to field only one candidate per constituency —the candidate of the party that had done best in the previous election— and to vote for all of them.[45]

Elections of April 1872

[edit]

The result of the general elections of April 1872 was a landslide victory for the Constitutionalists —they won an absolute majority, with more deputies from Unionist than Progressive backgrounds, which favoured General Serrano's leadership over Sagasta— thanks to the government exercising its ‘moral influence’ —the constitutionalist Andrés Borrego justified this by saying that the government had no choice but to ‘oppose the audacity of the oppositions with the audacity of the administrations’— despite the fact that the king had asked Sagasta for cleanliness, to which the latter had replied that the elections would be ‘as pure as they can be in Spain’.[46] A circular that Sagasta sent to the civil governors instructing them on how to act in the elections stated, among other things, the following:[47]

With the help of second-rate republicans, but influential among the masses, and with the necessary secrecy, the governor should buy as many cédulas as possible from federal electors for two reales or pesetas. On the day of the election, half an hour before the opening of the polling stations, a considerable number of royalist electors should crowd at the door of each one, enough to completely occupy the hall of the polling station... which should only admit those who are convenient. It seems to me that I am justified in warning that the authorities must have at the door of each polling station public order officers with heart and energy, who will do well, at the slightest pretext, to hand out a few sticks and immediately take to prison those who give cause for this. At the opening of the polling station, which must take place half an hour before nine o'clock in the morning, for which the president and the secretary must set their watches half an hour ahead of time, there must be as many votes in the ballot boxes in favour of the ministerial candidate as there are bought votes in the possession of the governor.

The Republicans and Carlists lost deputies —strengthening their respective intransigent wings that had opposed participation in the elections— but the big losers were the Radicals, who won only 42 seats, less than even the Republicans - which called into question Ruiz Zorrilla's leadership and also led them to consider abandoning the "legal route" to government.[46] However, the sum of the Radicals, Carlists, Federalists and Alfonsinos moderates was not negligible, as together they accounted for almost 150 deputies.[48] In the April elections there was a large abstention due to the campaign promoted by the 'intransigent' Republicans and general disinterest,[49] and there was also unrest in the Carlist provinces —the Basque Country and Navarre— and the Federalist provinces —those on the Mediterranean coast—.[50]

Thus, with the elections of April 1872, the 'legal' dissolution of the Progressive Party was completed, since the alliance of the sector led by Sagasta with the Liberal Union of General Serrano gave rise to a new party, the Constitutional Party, while Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla remained at the head of the Radical Party, the result of the union of his group of advanced progressives with the monarchist democrats or [[Cimbri|cimbrios]] led by Cristino Martos and Nicolás María Rivero.[30]

Carlist uprising

[edit]

In the elections of April 1872, the Carlists suffered a relative setback, dropping from 51 to 38 deputies, and the supporters of the 'insurrectionary path' won over the neo-Catholics of Cándido Nocedal, the advocates of the parliamentary path. Thus, "the Carlists changed their position, fulfilling the last sentence of the manifesto of 8 March: 'now to the ballot box, then to wherever God calls us', that is, to war."[51]

On 14 April, the pretender Charles VII elected deputies not to attend the Cortes and for the armed insurrection to begin, which had been planned and organised long beforehand in case the strategy of Cándido Nocedal —who immediately resigned from all his posts— failed.[52] Don Carlos (VII) proclaimed in a manifesto the reasons for the uprising and called on all Spaniards to join him:

The holy religion of our fathers is persecuted, the good is oppressed, immorality is honoured, anarchy triumphs, the treasury is plundered, credit is lost, property is threatened, industry is exanimated... If this continues, the poor will be left without bread and Spain without honour. Our fathers would not have endured so much; let us be worthy of our fathers. For the sake of our God, for the sake of our country and for the sake of your King, rise up, Spaniards!

Thus began the Third Carlist War. On 2 May, the Carlist pretender entered Spain via Vera de Bidasoa, shouting 'Down with the foreigner and long live Spain!'. Two days later, the Battle of Oroquieta was fought, in which the Carlists were defeated and the Pretender was forced to flee to France. In the absence of a visible leader of the rebellion, General Serrano, who commanded the army of the north and had just received word from the King that he had been entrusted with the presidency of the government following Sagasta's resignation, signed on 24 May with the 'deputies to the war' of the Biscay Provincial Council, which had proclaimed themselves in favour of the Carlist pretender, the Amorebieta Convention, which put an end to the conflict by granting amnesty to all rebels who surrendered their arms and included an article (the 4th) which reinstated the chiefs and officers who had joined the rebellion. This last concession was widely criticised within the army and by the radical and republican opposition as being too generous to the rebels and because General Serrano had assumed powers he did not have.[53]

The Amorebieta Convention put an end to the war in the Basque-Aragon region, but the Carlist parties continued to operate in Catalonia —on 16 June the Pretender promised to restore the Catalan fueros, which had been abolished by Philip V in the Nueva Planta decrees of 1714—[54] until December 1872, when a new insurrection took place in the Basque-Aragon region —the war would continue beyond the reign of Amadeo I until 1876—.[55]

Fall of the Sagasta government and the 'lightning' government of Serrano: the end of the conservative project

[edit]Sagasta's government was short-lived, because the month after the elections a scandal broke out that brought him down. On 11 May, a republican deputy asked him to account for the destination of two million reales that had been diverted by government order from the Ministry of Overseas Territories to the Ministry of the Interior, presumably to be used in the electoral corruption operations —one of the methods used was that of 'lázaros', the use of deceased people to increase the number of voters dependent on government candidates—.[56] It was also said that the money was used to avoid the scandal of a love affair between one of King Amadeo's or General Serrano's wives and one of his aides, but it seems certain that the money was spent on electoral corruption.[48]

Sagasta's government gave no satisfactory explanation of where the money was spent. It claimed that it had been used to make payments of a reserved nature to prevent conspiracies, but the papers it produced to justify this were forged and recorded the payments without any authorisation and showed that correspondence had been breached.[48] "Trapped, the President of the Council of Ministers asked for a vote of confidence from the majority that supported him, but this was refused. The Unionists were less concerned with the fate of the two million than with the illegalities and the image of a conservative party and government that had just begun its journey." On 22 May, Sagasta submitted his resignation to the King.[57]

Four days later, Amadeo I appointed General Serrano, who was then in charge of the northern army fighting the Carlists, as the new president of the Council of Ministers. The King thought that Serrano could govern because his party still had a majority in the Cortes. In fact, the government he formed included three former Progressives and five former Unionists, one of them from the faction led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, who had recognised Amadeo I but was an Alfonsin.[58]

The presentation of the new government to the Congress of Deputies on 27 May 1872 was made by the interim president, Admiral Topete, as Serrano had not yet returned to Madrid. The surprise came when Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla announced that he would give loyal, legal and respectful opposition to the new government and that he wanted it to complete its term of office, which meant a complete change of attitude because it meant accepting the rules of constitutional monarchy, which was immediately contested by many members of his party, led by Cristino Martos, who were not prepared to wait two or three years for access to power or to collaborate with 'reaction' in this way. When his position was not supported by the majority of his party, Ruiz Zorrilla resigned his parliamentary seat on 31 May, the day after meeting the King at a ceremony in the Palace to celebrate his birthday, and retired to his Soria estate, 'La Tablada', claiming that he lacked the energy to continue in politics. According to Jorge Vilches, 'Ruiz Zorrilla did not want to be part of the anti-dynastic and probably insurrectionary path that democratic progressivism was about to take, nor did he want to feel complicit in a new civil war'. For its part, the press, which was sympathetic to the Radical Party, blamed the King and Queen for Ruiz Zorrilla's departure.[59]

Meanwhile, the signing of the Amorebieta Convention almost brought down Serrano's government, as all the ministers initially opposed it, especially the fourth provision, which reinstated rebel officers in the military establishment. They considered this to be "a degradation of the dignity of our army [prominent generals had protested to the Minister of War] and of the government that sanctioned it". However, the King's support for Serrano ended the crisis and the Amorebieta Convention was ratified not only by the government but also by the Cortes, where only the Republicans voted against it, while the Radicals abstained. On 4 June, Serrano was sworn in as the new head of government.[60]

Despite having overcome the parliamentary process, the Radicals —now led by Martos after Ruiz Zorrilla's withdrawal from political life— and the Republicans questioned the legitimacy of Serrano's government, partly because he had included an Alfonsist in it.[61] Pre-revolutionary rhetoric spread through the radical and republican press, with slogans such as "The Revolution is dead! Long live the Revolution!" and criticism not only of Serrano's conservative government but also of the monarchy. An article published in El Imparcial on 10 June implicitly referred to the Queen in an article entitled "The Madwoman of the Vatican".[62]

On 6 June, just two days after Serrano's inauguration, the radicals called on the national militia, particularly Madrid's Volunteers of Liberty, to demonstrate against the government in the Plaza Mayor. In response, the government ordered the troops and the Civil Guard to be quartered and, on 11 June, requested the King's signature on a decree suspending constitutional guarantees —a measure approved by the Cortes— in order to quell what appeared to be an imminent republican uprising, which the radicals appeared ready to join now that Ruiz Zorrilla had retired to his estate in Soria. They had planned a meeting for 16 June under the slogan "The September Revolution and the Freedom of the Motherland", which for the first time made no mention of the dynasty. Fearing that the radicals would turn definitively against the monarchy and that a serious civil conflict might break out, Amadeo I refused to sign the decree. As a result, General Serrano resigned. That same day, 12 June 1872, the battalions of the National Militia gathered in the Plaza Mayor, but dispersed when they heard of the government's resignation.[63]

General Serrano, "without even completing twenty days in office", "retired to his estates in Arjona and refused to stand in the new elections, thus eliminating himself as a governing alternative for the radicals (it was at this time that he told a French diplomat, referring to the King: 'We must get rid of that imbecile')".[61]

As Jorge Vilches noted after Serrano's resignation:[64]

"The king was almost completely isolated in a country with a strong anti-dynastic opposition, weak constitutional parties —the conservatives only formed because he forced them to, and the radicals' loyalty was proportional to their proximity to power. Moreover, the political leaders lacked the ability to unite and lead, and the people did not support him. By 12 June 1872, his situation was dire: his main mentor, Prim, was dead; another, Ruiz Zorrilla, had retired; and the last, Sagasta, was about to be prosecuted. The Radical Party was torn between temporary loyalty to the dynasty and republicanism. The Conservative [Constitutional] Party felt ignored and would soon feel even more humiliated, for a Radical government could not function with opposing legislative chambers. Meanwhile, the country was embroiled in two civil wars - the Carlist and the Cuban —and another looming threat, the Republican insurrection. Moreover, only a month later, the King and Queen survived an assassination attempt as they strolled down the Arenal Street in Madrid.

When the constitutionalists heard that the king had appointed Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla as the new president of the Council of Ministers and had ordered the suspension of the Cortes sessions from 14 June, thus dissolving them, they called a meeting of their deputies and senators. Francisco Romero Robledo denounced the "unprecedented and shameless coup d'état" and they agreed to petition the King not to grant Ruiz Zorrilla's condition for accepting the premiership —the dissolution of the Cortes and the calling of new elections— because, apart from being unconstitutional —the required four months had not elapsed since the last elections—, it would further destabilise the regime. In just a year and a half, there had been three parliamentary elections, one local election, two early dissolutions, two suspensions of sessions, numerous partial government crises and six total crises. In return, they promised to support the new government.[65]

Second Ruiz Zorrilla government: failure of the Radicals

[edit]

After Serrano's resignation, the King asked General Fernando Fernández de Córdoba to form a government until Ruiz Zorrilla returned. As a result, criticism of the monarchy in the radical press ceased. Up to three hundred radicals, led by Nicolás María Rivero, José María Beránger and Francisco Salmerón, travelled to La Tablada to persuade Ruiz Zorrilla to return to Madrid and take charge of the government. Several thousand supporters greeted him on his arrival in the capital. Ruiz Zorrilla demanded that the King dissolve the Cortes and call new elections, knowing full well that this was unconstitutional since the last elections had been held less than four months previously. However, Amadeo I accepted what Jorge Vilches describes as blackmail, leading to the perception that he was no longer "a king for all Spaniards, an arbiter of institutions and parties", but rather a monarch aligned with a single party —the Radicals.[66] According to Jorge Vilches, the actions of the radicals —first to force their way into power by threatening an uprising, and then to force the King to dissolve the Cortes in violation of the Constitution "can undoubtedly be described as a coup d'état".[67]

Manuel Ruiz Zorrilla formed his government on 13 June, taking over the Ministry of Government himself. His cabinet included two former democrats —Martos in State and Echegaray in Public Works— and four former progressives —Eduardo Gasset y Artime in Overseas, Servando Ruiz Gómez in Finance, Eugenio Montero Ríos in Mercy and Justice and Beránger in the Navy—, as well as General Fernández de Córdoba as Minister of War. Nicolás María Rivero was promised the presidency of the Congress of Deputies after the elections.[68] This was followed by *"the usual purge of civil servants, with 40,000 dismissed in order to install an equal number of loyalists".[69]

Assassination attempt against the King on July 18 and insults to the Crown

[edit]

The king’s sense of isolation, now relying solely on the support of Ruiz Zorrilla’s Radicals, was exacerbated by the assassination attempt he suffered on Madrid’s Calle del Arenal on July 18, along with his wife. Though they survived, the incident left him deeply shaken.[70]

"By chance, a friend of Topete learned that Amadeo was to be assassinated on July 18, and he informed Martos, who in turn warned the king and Pedro Mata, the civil governor of Madrid. The monarch refused to change his planned route despite Queen Vittoria’s insistence, so Mata stationed agents along the entire path, instructing them to wait until the would-be regicides fired before arresting them. The governor’s handling of the situation was harshly criticized... The perpetrators of the attack, [Republican] federalists from Madrid, were defended in court by lawyer Francisco Pi y Margall. This was not the only public humiliation suffered by the royals: their carriage was stopped and shaken on Calle de Alcalá by a demonstration of street vendors. On another occasion, they were pelted with mud while walking through Cedaceros. One day, near El Retiro, a man approached the monarch and insulted him to his face. Another person entered the royal grounds armed. They were even struck with a stone during a nearby Republican demonstration at the Royal Palace. And this does not include the insults from the aristocracy, such as the famous 'mantillas' incident, the snubs in theater boxes—where the king was often mocked—and the social ostracization suffered by Queen Maria Vittoria. Their stay in Spain was far from pleasant."[71]

August 1872 elections and its consequences

[edit]In the August 1872 elections, the Radicals presented an ambitious reform program, which included trial by jury, the abolition of conscription and maritime enlistment, the separation of church and state, the promotion of public education, and the strengthening of the National Militia, among other measures.[49] Through this program, the Radicals aimed to fulfill the promises made to the "fourth estate", the popular classes, during the Revolution of 1868, thus bringing it to completion.[72]

The call for elections sparked a difficult debate within the Constitutional Party between those who advocated participation —despite knowing they would be defeated due to government influence— and those who supported abstention, arguing that the elections were unconstitutional and referring to Amadeo I as "the captive King" of the Radicals. Ultimately, the party’s board decided on July 5 to participate, fearing that their absence in the Cortes would facilitate the proclamation of a Republic if the Radical Democrats led by Martos and Rivero abandoned Ruiz Zorrilla and joined the federalists. However, the decision was met with little enthusiasm by local party committees, and certain of their defeat, the Constitutionalists fielded very few candidates, presenting none at all in half of the provinces.[73]

Abstention, according to Ángel Bahamonde, constituted "a dangerous stance that questioned not only the elections themselves but the entire system,"[70] compounded by the fact that the leader of the Constitutional Party, General Serrano, also refused to run, meaning he would not be able to succeed Ruiz Zorrilla in government under parliamentary conventions. According to Jorge Vilches, "Serrano bore significant responsibility for the viability of the Savoy dynasty, as he was the declared leader of the other dynastic party, theoretically meant to alternate power with the Radicals. His withdrawal could only be interpreted as an acknowledgment that the experiment had failed."[74] His leadership of the Constitutional Party was taken over by Admiral Topete, Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, and Antonio Ríos Rosas, who still believed in the "democratic monarchy" of Amadeo I, though they continued to regard Serrano as the party’s president.[75]

The elections, held on August 24, 1872, and heavily influenced by government intervention, resulted in a victory for the Radical Party candidates —274 deputies, against 77 Republicans, 14 Constitutionalists, and 9 Moderates. However, more than half of eligible voters abstained due to the Constitutional Party’s boycott, the abstention campaign led by the Carlists and some Republicans (who argued that elections were rigged since the ruling government always won), and general apathy caused by widespread political illiteracy.[70][76] There was a tacit agreement between the Radicals and the "benevolent" Republicans, orchestrated by Minister Cristino Martos, to refrain from running candidates against each other in districts where either faction had a strong presence.[67]

According to Jorge Vilches, "the impact of the election results on the credibility of the [1868] Revolution among the middle and conservative classes was overwhelmingly negative, as the regime veered sharply to the left following a series of illegal actions by the government, all endorsed by Amadeo I. This eliminated the Constitutional Party as a dynastic alternative to the Radicals and as a representative of their interests."[77] Consequently, many began to view Amadeo I as a partisan king, aligned with the Radicals, and started considering the restoration of the Bourbons under Prince Alfonso as an alternative, seeing him as "free from the errors of [his mother] Isabella II."[78]

The alternative of Prince Alfonso gained renewed traction in April 1872 when his uncle, the Duke of Montpensier, acting on behalf of the former regent María Cristina of Bourbon, recognized him as the legitimate heir to the dynasty. In a public letter dated June 20, Montpensier presented Alfonso as a monarch who would not revert to "laws and institutions that have already expired" but would instead embrace whatever "fruitful, useful, and good" had emerged from past crises and revolutions. Additionally, the more liberal Alfonsine Moderates —who believed that a return to the Constitution of 1845 was no longer feasible— began aligning themselves with former Unionists led by Antonio Cánovas del Castillo. Cánovas, having been excluded from the Cortes due to government pressure in both districts where he ran, had already concluded that Amadeo I’s "democratic monarchy" was a failure, arguing that it had been unable to reconcile order with liberty.[79]

Abolition of slavery project in Puerto Rico

[edit]On September 15, 1872, the government of Ruiz Zorrilla presented its announced reform program in the Cortes, but only managed to pass the new Criminal Procedure Law despite its broad majority in Congress.[70]

One of the most important reforms proposed by the new government, the abolition of slavery in the Antilles colonies, created tensions within its ranks because the Minister of Overseas, Eduardo Gasset y Artime, supported maintaining the agreement of the 1869 Constituent Cortes not to introduce reforms in Cuba until the insurrection ended, as well as the "Moret Law."[80] When the government proposed the immediate abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico, accompanied by the implementation of the provincial regime on the island and the separation of political and military authority, Gasset y Artime resigned —followed by the Minister of Finance, Ruiz Gómez, who stood in solidarity with him. They were replaced by Tomás María Mosquera, who presented the project on December 24, 1872, making it coincide with "the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ, the savior of the oppressed, with the announcement of the liberation of the slaves."[81] This project was supported by the Republicans within the chamber and by the Spanish Abolitionist Society outside it. According to Ángel Bahamonde, pressure from the Centro Hispano Ultramarino de Madrid, which brought together merchants and businessmen with interests in the sugar plantations in the Antilles and the slave trade, ensured that the government did not extend its project of immediate abolition to Cuba.[70] Meanwhile, the Carlist pretender Carlos VII even offered to send to Cuba those fighting for him in Catalonia and Navarre to defend "the integrity of the homeland."[82]

The conservatives considered that these changes put Spanish interests in Puerto Rico at risk because immediately freeing the 30,000 plantation slaves —despite the fact that owners would be compensated and slaves would retain the status of freedmen for several years— would destabilize the island. Granting the provincial regime would allow municipalities to organize their own armed forces and oppose government policy, as was already happening in the metropolis. Finally, dividing military and civil command would weaken the state's authority to repress the independence movement. Furthermore, these measures together would have a negative effect on Cuba by encouraging the rebels. "The radicals, on the other hand, trusted that a gesture of goodwill from the government would show the independence fighters that through peace, they could obtain the improvements promised by the revolution."[83]

Faced with a situation in which the Constitutional Party had only 14 deputies in the Cortes, opposition to the reforms in Puerto Rico was led by the Centros Hispano Ultramarinos, which had emerged in late 1871 as pressure groups aiming to oppose the immediate abolition of slavery in Cuba and Puerto Rico and any changes that would harm their members' interests. Their motto was "Spanish Cuba," and they pressured Amadeo I not to sign the government’s decrees on colonial regime reforms. In late 1872, the Centros Hispano Ultramarinos were joined by the Constitutional Party under Serrano, who returned to political life for this cause, and by Adelardo López de Ayala. The Moderate Circle, led by the Count of Toreno and Manuel García Barzanallana, also joined, as did the Liberal Union Circle —of which Cánovas was a member—and the Spanish Grandee nobility led by the Duke of Alba. When the government presented its project for the abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico on December 24, the Centros Hispano Ultramarinos formed a National League that issued a Manifesto to the nation, written by López de Ayala, calling for the reforms to be halted. "The National League did not seek to destabilize the regime or change the dynasty... The replacement of the Ruiz Zorrilla government with a conservative one, including Augusto Ulloa, Ríos Rosas, Sagasta, Topete, or Serrano, would have guaranteed the satisfaction of their demands without deviating from the Constitution, as these figures would have halted the reform process."[84]

Halted reforms and division among the Radicals

[edit]As had happened with previous governments, the Carlist War and the Cuban War prevented Ruiz Zorrilla from fulfilling his promise to abolish military drafts, so when he announced a new recruitment, riots broke out in several cities, encouraging "intransigent" federal Republicans to continue defending the insurrectionary path. The most serious uprising by these groups took place on October 11, 1872, in Ferrol, but it failed due to lack of support in the city and because, contrary to the rebels' expectations, it was not followed elsewhere. Moreover, the leadership of the federal Republican Party, dominated by the "benevolents," condemned the insurrection. As Francesc Pi i Margall stated in the Cortes on October 15, the uprising was a "true crime" when "our individual freedoms are fully guaranteed."[85] The condemnation worsened the tensions already present in the party between supporters of the "legal path," like Pi, and defenders of the "insurrectionary path," to the point that only the proclamation of the Republic four months later prevented another uprising.[86]

To all this was added the intensification of the Third Carlist War starting in December 1872,[55] so once again, the abolition of drafts was postponed, leading to rejection by the Republicans, with some rebel groups forming in Andalusia, though they were much less dangerous than the Carlists.[86]

Given the difficult situation, Ruiz Zorrilla sought to restore relations with the Constitutional Party by proposing that Sagasta be judged not by the Senate but by ordinary courts for the "two million reales scandal"—the issue that had cost him the government. However, he faced rebellion from deputies of democratic origin led by the Speaker of the Congress, Nicolás María Rivero, and two of his ministers, Martos and Echegaray, who voted alongside the Republicans to reject the proposal. This division within the governing party encouraged the "benevolent" Republicans to continue their strategy of attracting former democrats cimbrios to their side and securing a parliamentary majority to end the monarchy and proclaim the Republic.[87]

Abdication of Amadeo I and proclamation of the Republic

[edit]Conflict between Radicals and the King

[edit]On January 29, 1873, the most extreme radicals used a supposed slight by the King toward the Cortes as a pretext —he had postponed the baptism of his newborn heir by a day due to complications in childbirth, while the government and the presidents of the Congress and Senate, dressed in formal attire for the occasion, waited in a palace antechamber. At the same time, there were rumors that the king intended to dismiss the government and replace it with one from the Constitutional Party— since it was known that he had met with General Serrano at the palace for the baptism, though Serrano declined the invitation after consulting his party’s leadership to avoid the appearance of softening his opposition to the radical government. The radicals proposed in the Cortes that it declare itself in permanent session as a Convention, a move only thwarted by the swift arrival of the government. However, the Chamber merely acknowledged the birth of the prince without any celebrations or speeches. The king expressed his displeasure to Ruiz Zorrilla, stating he was "not willing to suffer impositions from anyone" and was "prepared to act according to circumstances." Amadeo I wrote to his father in early February that he was considering abdicating because:[88]

I saw that my minister, instead of working to consolidate the dynasty, was working, in agreement with the Republicans, for its downfall.

Another conflict, which was to prove decisive, pitted the government and the Cortes against the king. In January 1873, artillery officers had challenged the government and threatened to resign if it maintained General Hidalgo as Captain General of the Basque Country. They accused him of collaborating in the suppression of the failed uprising at the San Gil barracks in June 1866. The government's response, with the support of the Cortes, was to reaffirm the supremacy of civilian power over the military by upholding the appointment and proceeding with the reorganisation of the artillery corps. As a result, the officers kept their promise and resigned en masse.[89]

On 6 February, a delegation of the resigned artillery officers met with the King, asking for his intervention in their conflict with the government and offering their support for a coup that would dissolve the Cortes and temporarily suspend constitutional guarantees until new elections could be held to approve greater prerogatives for the Crown. The King rejected the coup proposal, but promised to oppose the government's plans to reorganise the artillery corps.[90]

Later that day, the king summoned Ruiz Zorrilla to the palace after reading in the press that the government intended to appoint General Hidalgo as the new Captain General of Catalonia. The president assured him that the news was false, but the next day the appointment was confirmed. The king then realised "that Zorrilla had lied to me". He tried to persuade the government to reverse its decision, calling Ruiz Zorrilla on the morning of 7 February and again in the afternoon when he heard that the issue of reorganising the artillery was being discussed in the Congress of Deputies. He advised Zorrilla to delay the matter and not to accept the resignations of the artillery officers, citing the ongoing Carlist war. According to the King, Ruiz Zorrilla agreed, but later that day the Cortes approved the acceptance of the resignations of the artillery officers, their replacement by sergeants and the reorganisation of the corps. The next day, 8 February, the Senate ratified the decision of the Congress, although the moderate Fernando Calderón Collantes warned the government that the measures approved were an attack on the King's prerogatives, since it was known that the Crown opposed them. The King felt betrayed once again —especially as the officers in Madrid were forced to hand over their weapons to the sergeants that very morning, even before he had signed the decree—.[91]

The king believed his only alternative was to appoint a government from the Constitutional Party and dissolve the Cortes, but, as Amadeo I wrote to his father in a letter, "to dissolve the chamber, it was necessary to resort to force," which could lead to civil war. The king could count on the support of the most important conservative generals —Topete, Serrano, and Malcampo— but the capital's garrison was under the command of officers loyal to the Radical Party.[92] In fact, that same Friday, February 7, Admiral Topete visited the king at the palace, offering him the support of his party, the Constitutionalists, and that of the Unionist generals, the most prestigious figures in the army. The next day, Saturday, February 8, Topete returned to the palace, but the king told him that he did not want blood to be shed on his behalf and that he would sign the decree reorganizing the artillery corps.[93]

Thus, Amadeo I abandoned the option of a coup, and when he presided over the Council of Ministers on Saturday, February 8, he signed the decrees concerning the artillery officers, as they had been ratified by the Cortes. However, he noted that this issue fell under the jurisdiction of the Executive, which, according to the 1869 Constitution, was held by the king, not the Legislative. "The king kept Ruiz Zorrilla after the Council of Ministers to tell him that he was disappointed in him because, having believed him loyal to the dynasty and what it represented, he had instead been blinded by party interests." He then presented his idea of forming a government of national reconciliation, including all the parties that had supported his election in November 1870. Otherwise, he had no choice but to abdicate.[92]

Ruiz Zorrilla convened his cabinet three times to discuss the king's proposal of forming a reconciliation government with Serrano and Sagasta's Constitutionalists, knowing that the continuity of Amadeo I's reign was at stake. But the proposal was rejected. When this became known on Sunday, February 9, the Constitutional Party decided to offer itself to the king once again, sending a telegram to General Serrano, who was in Jaén, instructing him to return to Madrid immediately. The next day, Monday, February 10, Serrano arrived in the capital and informed the king that he was willing to form a government and defend the dynasty. However, that same day, a special edition of the most widely circulated newspaper, La Correspondencia de España, reported that Amadeo I had renounced the throne.[94]

Abdication

[edit]The king was forced to sign the decree reorganizing the artillery corps, which was published on February 9. The following day, Monday, February 10, 1873, he renounced the Crown.[82] This was the message the king sent to the Cortes:[95]

[...] For over two years I have worn the Crown of Spain, and Spain lives in constant struggle, seeing the era of peace and prosperity that I so ardently long for grow ever more distant. If the enemies of its well-being were foreigners, then, at the head of these soldiers —so brave and yet so long-suffering—, I would be the first to fight them. But all those who, with the sword, with the pen, with words, aggravate and perpetuate the nation's suffering are Spaniards; all invoke the sweet name of the Motherland; all fight and stir in its name. Amid the clamor of battle, amid the confused, deafening, and contradictory cries of the parties, amid so many opposing manifestations of public opinion, it is impossible to discern the true one, and even more impossible to find a remedy for such great ills. I have sought it eagerly within the law, and I have not found it. He who has sworn to uphold the law must not seek it outside of it. No one will attribute my decision to weakness of spirit. No danger would compel me to lay down the crown if I believed that wearing it would be for the good of the Spanish people. Not even the threat to the life of my august wife shook my resolve, and at this solemn moment, she, like myself, expresses the wish that those responsible for that attack be pardoned. But today I hold the firm conviction that my efforts would be futile and my intentions unattainable. These, gentlemen deputies, are the reasons that lead me to return to the nation, and to you in its name, the crown that was offered to me by the national vote, renouncing it for myself, my children, and my successors. Be assured that, in relinquishing the Crown, I do not relinquish my love for this Spain —so noble yet so unfortunate— and that my only regret is that I have not been able to bring it all the good that my loyal heart wished for it. — Amadeo, Palace of Madrid, February 11, 1873.

One of the few revolutionaries of 1868 who came to bid farewell to the king and queen after their abdication was Admiral Topete. Though he had initially supported the candidacy of Montpensier, he became a loyal servant of Amadeo I once he was elected by the Cortes.[96]

According to historian Jorge Vilches, the primary responsibility for the downfall of Amadeo I’s monarchy lies with Ruiz Zorrilla’s Radicals because they "distorted the role of the Crown within the constitutional monarchy they had built. They reduced it to a mere sanctioning power, making it impossible to establish a system of dynastic parties that were loyal both to the regime and to each other, whether in government or opposition. They empowered the regime's enemies through their electoral and parliamentary alliances and by questioning the legitimacy of conservative governments. They expelled the Constitutionalists from institutions, turning what should have been mere programmatic disputes into moments of regime change." However, Sagasta, Serrano, and their respective followers also bear some responsibility. Sagasta, because "he hesitated in forming the Conservative Party," and Serrano, because he and his supporters "quickly deemed the Amadean experiment a failure and refused to support the monarch when he summoned them to the palace, snubbing him merely because their attendance could be seen as backing Ruiz Zorrilla’s government." In conclusion, Vilches asserts that "the state of the parties and the men of the revolution was what led to Amadeo I’s abdication, as he found himself without support or a legal, peaceful way forward."[97]

Proclamation of the Republic

[edit]On Monday, February 10, as soon as the newspaper La Correspondencia de España reported that the king had abdicated, Madrid’s federalists gathered in the streets demanding the proclamation of the Republic. The government convened, and opinions within it were divided. The president and the ministers of progressive origin sought to establish a provisional government to organize a national consultation on the form of government —a position also supported by the Constitutional Party, as this would prevent the immediate proclamation of the Republic. On the other hand, the ministers of democratic origin, led by Cristino Martos and backed by the president of the Congress of Deputies, Nicolás María Rivero, favored the joint meeting of the Congress and the Senate, which, once constituted as a Convention, would decide the form of government. Given the majority formed in both chambers by federal republicans and radical democrats, this would inevitably lead to the proclamation of the Republic.[98]

President Ruiz Zorrilla went to the Congress of Deputies to ask members of his own party, who held an absolute majority in the Chamber, to approve the suspension of sessions for at least twenty-four hours, enough time to restore order. He also requested that no decision be made until the king’s formal abdication letter reached the Cortes and announced that the government would present an Abdication Law. With these measures, Ruiz Zorrilla intended to buy time, but he was overruled by his own Minister of State, Cristino Martos, who declared that as soon as the king’s formal renunciation arrived, power would belong to the Cortes and that “there will be no dynasty, no monarchy possible here —there is no other possibility but the Republic.” Consequently, the motion by republican Estanislao Figueras was approved, declaring the Cortes in permanent session, despite Ruiz Zorrilla’s attempt to dissuade the radicals from supporting it. Meanwhile, the Congress of Deputies building was surrounded by a crowd demanding the proclamation of the Republic, although the National Militia managed to disperse them.[99]