Draft:Emergent Norm Theory

| Submission declined on 29 January 2025 by Devonian Wombat (talk). This submission reads more like an essay than an encyclopedia article. Submissions should summarise information in secondary, reliable sources and not contain opinions or original research. Please write about the topic from a neutral point of view in an encyclopedic manner.

Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

|  |

Comment: This is written like a university course paper, not an encyclopedia article. Devonian Wombat (talk) 22:36, 29 January 2025 (UTC)

Comment: This is written like a university course paper, not an encyclopedia article. Devonian Wombat (talk) 22:36, 29 January 2025 (UTC)

Emergent Norm Theory

[edit]Social norms guide individuals’ behaviour in societies by providing expectations about whether behaviour by others is considered acceptable[1]. Whilst these rules are not rigid controls of human behaviour, abiding by these norms often develops an equilibria of behaviour necessary for coordination and cooperation between societal members[1]. In observation, social norms have arisen in response to social problems where behavioural norms typical of the society may not apply, and members develop new emergent norms to guide their behaviour in response. Emergent Norm Theory suggests that crowds are forced to abandon prior conceptions of appropriate behaviour in response to crises, and find alternative ways of behaving as a result.

Theoretical Basis

[edit]One of the earliest explanations of crowd behaviour was derived by Le Bon, who argued that when individuals become part of a crowd they become subject to a collective unconscious irrationality[2]. This explanation provided the basis for future theories on crowd behaviour, where crowds were presumed to be normless entities and described their collective action as irrational behaviour[3]. This became a paradigm in research into collective behaviour, which allowed further research development to eventually suggest an alternative perspective.

After the development of this theory and subsequent new paradigm about crowd behaviour, Ralph H. Turner and Lewis Killian suggested that crowd behaviour is not irrational, but instead a rational response to a broken-down social situation[4].This led to the consideration of how norms were manufactured in crowds, through small-group analysis and considering norm development through interaction. Norms emerge through interactions between agents in a bottom-up design of collective intelligence, which founded the proposal that crowd behaviour develops rationally as a result of the emergence of new behavioural norms[5].

Main Assumptions

[edit]Emergent Norm Theory (ENT) suggests that non-typical behaviour such as collective action develops in crowds due to the emergence of new norms in response to a crisis, overturning the typical frameworks for behaviour in society[3]. The theory describes collective action as a rational response to an ambiguous event, and that situation-specific norms emerge without prior coordination or planning[3]. ENT is specifically adapted to predict collective behaviour of individuals when involved in large crowds, looking to explain crowd behaviour[6]. Humans form new cognitions as a consequence of different or new behaviour within the social system, which causes them to act on the mental processes formed from being a part of the group[7]. When a crowd forms there is no governing body or leader who exists, and individuals within the crowd focus on others who display the most distinctive behaviour, causing individuals to model this distinctive behaviour developing an emergent norm[3].

Engineering emergent norms involves individuals detecting potential new norms, analysing these norms to conclude whether or not the norm is beneficial to the individual and the group system, and then assisting in the spread or destruction of the emergent norm through the group[3]. However, the theory is only applicable to situations where members are attached to a cause and seek to alter social behaviour to address this, ruling out application to mass movement phenomena, fan groups and groups removed from societal change such as cults[4]. Additionally, Turner and Killian proposed two main processes involved in the formation of emergent norms.

Key Processes

[edit]Milling

[edit]Milling refers to an important tool for collective decision making, where individuals faced with an unusual situation first discuss different event interpretations and then decide amongst the group what should be done[4]. In this stage, interactions within crowds allow individuals to search for more appropriate behaviours to enact in the unexpected situation[8]. Milling can be both a physical and verbal process, involving asking and answering questions about the situation and communicating information between group members.

Milling sensitises people to each other and facilitates social influence by having individuals engage with their surroundings and their peers reactions[5]. The transmission of information between crowd members reduces member uncertainty, and construction of a shared definition of the ambiguous situation compels individuals to form a basis for action[5]. After this stage, the basis for action is established by prominent members of the group who are perceived as leaders, suggesting that some individuals will behave in more distinctive ways to garner attention from other crowd members[9]. This links to the keynoting process Turner and Killian suggested will further aid emergent norms.

Keynoting

[edit]Keynoting occurs when members of the crowd begin to separate fact from fiction and have built a shared understanding of their situation[8]. Crowds introduce the concept of a role model to become an influence for providing advice in the situation[10]. This reduces the responsibility placed on individuals in the group to determine the best action to take, and will accept the role model as an advisor for their behaviour[10]. Keynoting itself is carried out by this role model, involving making positive statements in the ambiguous situation[5]. These individuals instil comfort in other group members this way, by making the situation less ambivalent and taking on a leadership role within the crowd. Keynote statements amongst a crowd facilitate the consideration of various interpretations of the situation they are in, and guides them to support the definition provided by the keynoter[5]. By this process, emergent norms are cultivated within a crowd and members can follow these new norms.

Theory in Application

[edit]Emergent norms in large crowds develop when individuals can interact with a range of norms stemming from various interpretations of the situation, generating unexpected behaviours in crowds which can have negative consequences when occurring in critical situations[6]. As an emergent norm is internalised by individuals in a crowd, social pressures for conformity and against deviance from the group occur[3]. This suppresses alternative views and behaviours, leading to the illusion of unanimity within crowds and causes individuals to all behave alike[3].

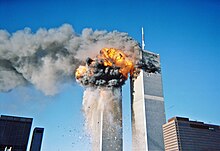

Evacuation of the World Trade Centre After 9/11 Attacks

[edit]Emergent norms can be observed in the examination of the World Trade Centre evacuation following the terror attacks on September 11th 2001. Since Turner and Killian described emergent norms forming in the case of a crisis and dependent on no prior guidance for decision making, the behaviour and norms observed in the stairwells can be attributed to emergent norms as the formal evacuation process did not account for such danger[11]. Instead, individuals experienced many barriers to following the emergency procedures and fleeing the danger became the main priority for individuals still inside the towers.

From survivors’ self-reports, emergent norms were developed to guide the movement of people through the stairwells in the evacuation process, noting that individuals enforced single-file movement to allow for emergency personnel to enter the buildings and ascend as quickly as possible in the limited width of the stairwells[11]. Additionally, it was noted that prosocial behaviours occurred whereby individuals allowed the descension of vulnerable individuals such as those with injuries and disabilities, but also prevented individuals from successfully deviating from this emergent norm by ‘cutting in line’ during the evacuation[12]. These emergent norms in the face of a crisis allowed an effective evacuation, despite the many unprecedented barriers to evacuation and the danger present in the situation.

January 6th US Capitol Riots

[edit]Emergent Norm Theory can also be seen influencing behaviour in the storming of the United States capitol on January 6th 2021. The riot began after a rally held by Donald Trump suggesting the presidential election had been frauded and his votes were being stolen, causing keynoting efforts of 12 rally speakers[6]. The keynoters primed the crowd by repeatedly suggesting there had been a theft, reducing crowd uncertainty in the situation as focussing on action to disrupt what was an alleged stealing, leading to the physical force used on police as the keynoters had provided crowd members with moral justification to do so[6]. Physical violence became an emergent norm as a result, with crowd members believing this was an acceptable norm under the circumstances of the situation. This example demonstrates how emergent norms can also be detrimental to public safety, and alternatively describes negative behaviour which can be typically associated with crowd behaviours.

Evaluation and Debate of Theory

[edit]In the following years after the Emergent Norm Theory was proposed, Jonathan Potter and Stephen Reicher suggested that when crowds form the individuals within them bring their own norms to the group, suggesting that new norms do not have to emerge[13]. This would suggest that crowd norms are dependent upon the demographic of the individuals within the group, reflecting the different ways crowds behave and demonstrates why a crowd with more even-tempered individuals may behave in a more regulated manner than a crowd with hot-headed individuals. This opposes the Emergent Norm Theory by dismissing the concept that emergent norms are an existing social process, provoking debate about the validity of ENT.

Further criticisms suggest that all social behaviour is the result of renegotiating social norms with others[3], which disputes the processes by which Turner and Killian proposed emergent norms are formed. Further studies into crowd behaviour have disputed the concept of Milling, by demonstrating that behavioural escalation in crowds can happen more rapidly than the time ENT suggests is needed to find a group-based logic[9]. This would also support prior theories such as Le Bon's explanation of crowd behaviour, since this describes crowd members as mindless entities willingly following simple situational cues. Alternatively, even violent and non-normative behaviour in crowds does suggest that behaviour does follow logic and is a rationalised response to a situation, making behaviour purposeful and in accordance with ENT.

There has also been debate around whether norm creation described as norm emergence is really created through interactions, or whether this is through stereotypical planning processes and adjusting these established repertoires in application to the situation[3]. This is a similar argument to other prior criticisms since it questions the processes by which emergent norms occur, and whether emergent norms are a falsifiable concept themselves. This has also led to some researchers describing the many methodological issues in being able to assess the emergence of norms in crowd settings. It is highly unlikely for researchers to observe the origins of behaviours when crowds are forming in real life settings, and simulated environments and situations lower ecological validity and generalisability to events in the real world. Methodological difficulties suggest that criticism and debate on ENT will continue, without a testable concept to provide researchers with valid and reliable evidence.

Finally, ENT is dependent on describing crowd behaviour in response to a precipitating crisis or unusual situation, which does not describe or explain crowd behaviour in situations where a crisis is not occurring. Crowding is a common occurrence in busy public places, and will not always involve the need to form a collective response to solve a problem. Individuals within a crowd may not act similarly to each other due to individual differences and varying characteristics between the group members, providing explanation for other prominent theories of crowd behaviour to describe unambiguous situations.

A Symbolic-Interaction Approach

[edit]Currently, ENT is still one of the only theories of collective behaviour that recognises individuals within crowds as separate entities who take on different roles. It also emphasises collectivity and promoting situational change through interactions between group members, demonstrating the effectiveness of social influence within large groups. This approach has many practical applications to crowd behaviour in real life, and aids researchers and advisors of public safety about the processes involved in developing both prosocial and antisocial crowd behaviour.

- ^ a b Haynes, Chris; Luck, Michael; McBurney, Peter; Mahmoud, Samhar; Vítek, Tomáš; Miles, Simon (2017). "Engineering the emergence of norms: a review". The Knowledge Engineering Review. 32: e18. doi:10.1017/S0269888917000169. ISSN 0269-8889.

- ^ "Review of The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind". Psychological Review. 4 (3): 313–316. 1897. doi:10.1037/h0069323. ISSN 1939-1471.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Arthur, Mikaila Mariel Lemonik (2022), "Emergent Norm Theory", The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1002/9780470674871.wbespm432.pub2, ISBN 978-0-470-67487-1, retrieved 2024-12-05

- ^ a b c Muukkonen, Martti (2008). "Continuing Validity of the Collective Behavior Approach". Sociology Compass. 2 (5): 1553–1564. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00141.x. ISSN 1751-9020.

- ^ a b c d e Turner, Ralph H.; Killian, Lewis M. (1987). Collective behavior (3rd ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- ^ a b c d Samuelson, Charles D. (2022). "Why were the police attacked on January 6th? Emergent norms, focus theory, and invisible expectations". Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 26 (3): 178–198. doi:10.1037/gdn0000183. ISSN 1930-7802.

- ^ Andrighetto, Giulia; Conte, Rosaria; Turrini, Paolo; Paolucci, Mario (2007). "Emergence In the Loop: Simulating the two way dynamics of norm innovation". Dagstuhl Seminar Proceedings, Volume 7122. Dagstuhl Seminar Proceedings (DagSemProc). 7122: 1–30. doi:10.4230/DagSemProc.07122.13.

- ^ a b Tahmasbi, Nargess; De Vreede, Gert Jan (2015). "A Study of Emergent Norm Formation in Online Crowds". AMICS 2015 Proceedings. 9.

- ^ a b La Macchia, Stephen T.; Louis, Winnifred R. (2016), McKeown, Shelley; Haji, Reeshma; Ferguson, Neil (eds.), "Crowd Behaviour and Collective Action", Understanding Peace and Conflict Through Social Identity Theory: Contemporary Global Perspectives, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 89–104, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29869-6_6, ISBN 978-3-319-29869-6, retrieved 2024-12-06

- ^ a b Morris-Martin, Andreasa; De Vos, Marina; Padget, Julian (2019-11-01). "Norm emergence in multiagent systems: a viewpoint paper". Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems. 33 (6): 706–749. doi:10.1007/s10458-019-09422-0. ISSN 1573-7454.

- ^ a b Connell, Rory (2001). "Collective Behavior In the September 11, 2001 Evacuation Of The World Trade Center". University of Delaware Disaster Research Center.

- ^ Proulx, G., Fahy, R. F., & Walker, A. (2001). Analysis of first-person accounts from survivors of the World Trade Center evacuation on September 11.

- ^ Potter, Jonathan; Reicher, Stephen (1987). "Discourses of community and conflict: The organization of social categories in accounts of a 'riot'". British Journal of Social Psychology. 26 (1): 25–40. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1987.tb00758.x. ISSN 2044-8309.