Draft:Defense of the Roman Republic (1849)

| Defense of the Roman Republic | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman question and the wars of Italian unification | ||||||||||

The final assault of the French on the bastions of the Aurelian Walls, Melchiorre Fontana | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

|

Garibaldine redshirts Italian republicans |

Separatist volunteers | ||||||||

|

|

Support by: |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

|

Siege of Rome: Unknown |

Siege of Rome: Up to 4,000 killed and wounded[3] 938 confirmed deaths[4] |

Battle of Velletri: 60–80 killed, 150 wounded, 75 captured[5] | ||||||||

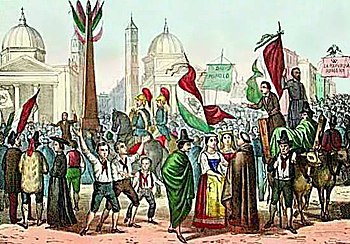

The Defense of the Roman Republic was used to refer to the actions interpreted by the governors and soldiers of the Roman Republic of 1849. The republic, at that time, was victim of neighbour states' ambition, like the Second French Empire (togheter with the Papal States), the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and Spain.

Prelude

[edit]Formation of the Roman Republic

[edit]

On 15 November 1848, Pellegrino Rossi, the Minister of Justice of the Papal States, was assassinated. The following day, the liberals of Rome, because of this victory, filled the streets, where various groups demanded a democratic government, social reforms and support for Italian irredentism, with the goal of capturing old territories from the Austrian Empire. And so, Pope Pius IX began to feel the effects of growing political opposition, and on the night of 24 November he left Rome disguised as an ordinary priest, and went to Gaeta, a fortress of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Already in the following days, in Rome the Civic Guard had occupied Castel Sant'Angelo and the city gates.

Pius IX placed himself under the protection of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. He subsequently requested the intervention of the Catholic powers to restore order in the Papal States.

On 2 February 1849, at a political rally held in the Teatro Apollo, a young Roman ex-priest, the Abbé Arduini, made a speech in which he declared that the temporal power of the popes was a "historical lie, a political imposture, and a religious immorality."[7]

The Constitutional Assembly convened on 8 February and proclaimed the Roman Republic after midnight on 9 February. According to Jasper Ridley: "When the name of Carlo Luciano Bonaparte, who was a member for Viterbo, was called, he replied to the roll-call by calling out Long live the Republic!" (Viva la Repubblica!).[7] That a Roman Republic was a foretaste of wider expectations was expressed in the acclamation of Giuseppe Mazzini as a Roman citizen.

When news reached the city of the decisive defeat of Piedmontese forces at the Battle of Novara (22 March), the Assembly proclaimed the Triumvirate, of Carlo Armellini (Roman), Giuseppe Mazzini (Roman) and Aurelio Saffi (from Teramo, Papal States), and a government, led by Muzzarelli and composed also by Aurelio Saffi (from Forlì, Papal States). Among the first acts of the Republic was the proclamation of the right of the Pope to continue his role as head of the Roman Church. The Triumvirate passed popular legislation to eliminate burdensome taxes and to give work to the unemployed.[8]

As a result, many of the european powers wanted the Pope and its government back, and so the Defense of the Roman Republic began.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ "Siege of Rome | Summary | Britannica".

- ^ Dwight, Theodore (1895). The Roman Republic of 1849: With Accounts of the Inquisition, and the Siege of Rome, And Biographical Sketches. p. 18.

- ^ Gustav von Hoffstetter, Storia della repubblica di Roma del 1849, Turin, 1855, p. 318

- ^ Elenco dei caduti Archived 2 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine on the website www.comitatogianicolo.it

- ^ Zaccagnini, Roberto (1994). Velletri, 19 maggio 1849 e dintorni: la più organica e dettagliata ricostruzione della battaglia di Velletri durante la seconda Repubblica Romana. Scorpius. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018.

- ^ "The first pope to be photographed was not afraid of new technology". Aleteia. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ a b Ridley, Jasper (1976). Garibaldi. New York: Viking Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-670-33548-0.

- ^ Bollettino delle leggi e disposizioni..., p. 3

- ^ Mario Bannoni; Gabriella Mariotti. Vi scrivo da una Roma barricata. Conosci per scegliere. p. 207–208. ISBN 9788890377273.