Storyboard

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

| Part of a series on |

| Filmmaking |

|---|

|

| Glossary |

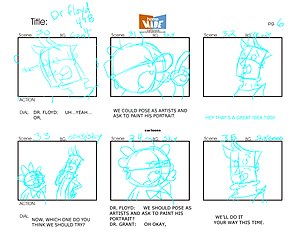

A storyboard is a graphic organizer that consists of crude illustrations or images displayed in sequence for the purpose of pre-visualizing a motion picture, animation, motion graphic, or interactive media sequence. The storyboarding process, in the form it is known today, was developed at Walt Disney Productions during the early 1930s, after several years of similar processes being in use at Walt Disney and other animation studios.

Origins

[edit]Many large budget silent films were storyboarded, but most of this material has been lost during the reduction of the studio archives during the 1970s and 1980s.[citation needed] Special effects pioneer Georges Méliès is known to have been among the first filmmakers to use storyboards and pre-production art to visualize planned effects.[1] However, storyboarding in the form widely known today was developed at the Walt Disney studio during the early 1930s.[2] In the biography of her father, The Story of Walt Disney (Henry Holt, 1956), Diane Disney Miller explains that the first complete storyboards were created for the 1933 Disney short Three Little Pigs.[3] According to John Canemaker, in Paper Dreams: The Art and Artists of Disney Storyboards (1999, Hyperion Press), the first storyboards at Disney evolved from comic book-like "story sketches" created in the 1920s to illustrate concepts for animated cartoon short subjects such as Plane Crazy and Steamboat Willie, and within a few years the idea spread to other studios.

According to Christopher Finch in The Art of Walt Disney (Finch, 1995),[4] Disney credited animator Webb Smith with creating the idea of drawing scenes on separate sheets of paper and pinning them up on a bulletin board to tell a story in sequence, thus creating the first storyboard. Furthermore, it was Disney who first recognized the necessity for studios to maintain a separate "story department" with specialized storyboard artists (that is, a new occupation distinct from animators), as he had realized that audiences would not watch a film unless its story gave them a reason to care about the characters.[5][6][7] The second studio to switch from "story sketches" to storyboards was Walter Lantz Productions in early 1935;[8] by 1936 Harman-Ising and Leon Schlesinger Productions also followed suit. By 1937 or 1938, all American animation studios were using storyboards.

Gone with the Wind (1939) was one of the first live-action films to be completely storyboarded. William Cameron Menzies, the film's production designer, was hired by producer David O. Selznick to design every shot of the film.

Storyboarding became popular in live-action film production during the early 1940s and grew into a standard medium for the previsualization of films. Pace Gallery curator Annette Micheloson, writing of the exhibition Drawing into Film: Director's Drawings, considered the 1940s to 1990s to be the period in which "production design was largely characterized by the adoption of the storyboard". Storyboards are now an essential part of the creative process.

Use

[edit]Film

[edit]

A film storyboard (sometimes referred to as a shooting board), is essentially a series of frames, with drawings of the sequence of events in a film, similar to a comic book of the film or some section of the film produced beforehand. It helps film directors, cinematographers and television commercial advertising clients visualize the scenes and find potential problems before they occur. Besides this, storyboards also help estimate the cost of the overall production and save time. Often storyboards include arrows or instructions that indicate movement. For fast-paced action scenes, monochrome line art might suffice. For slower-paced dramatic films with an emphasis on lighting, color impressionist style art might be necessary.

In creating a motion picture with any degree of fidelity to a script, a storyboard provides a visual layout of events as they are to be seen through the camera lens. In the case of interactive media, it is the layout and sequence in which the user or viewer sees the content or information. In the storyboarding process, most technical details involved in crafting a film or interactive media project can be efficiently described either in a picture or in additional text.

During principal photography for live-action films, scenes are rarely shot in the sequence in which they occur in the script. It is also sometimes necessary to film individual shots within a scene out of order and on different days, which can be very confusing. (The reasons for this are explained at length in the production board article.) In the latter scenario, directors can use storyboards on set to quickly refresh their memory as to the desired effect when those shots are later edited together in the correct order.[9] This is more efficient than having to reread the script for each shot (with cast and crew waiting) to refresh their memory as to how they originally visualized they would film that shot.[9]

Theatre

[edit]A common misconception is that storyboards are not used in theatre. Directors and playwrights frequently[citation needed] use storyboards as special tools to understand the layout of the scene.[10] The great Russian theatre practitioner Stanislavski developed storyboards in his detailed production plans for his Moscow Art Theatre performances (such as of Chekhov's The Seagull in 1898). The German director and dramatist Bertolt Brecht developed detailed storyboards as part of his dramaturgical method of "fabels."[citation needed]

Animatics

[edit]In animation and special effects work, the storyboarding stage may be followed by simplified mock-ups called "animatics" to give a better idea of how a scene will look and feel with motion and timing. At its simplest, an animatic is a sequence of still images (usually taken from a storyboard) displayed in sync with rough dialogue (i.e., scratch vocals) or rough soundtrack, essentially providing a simplified overview of how various visual and auditory elements will work in conjunction to one another.

This allows the animators and directors to work out any screenplay, camera positioning, shot list, and timing issues that may exist with the current storyboard. The storyboard and soundtrack are amended if necessary, and a new animatic may be created and reviewed by the production staff until the storyboard is finalized. Editing at the animatic stage can help a production avoid wasting time and resources on the animation of scenes that would otherwise be edited out of the film at a later stage. A few minutes of screen time in traditional animation usually equates to months of work for a team of traditional animators, who must painstakingly draw and paint countless frames, meaning that all that labor (and salaries already paid) will have to be written off if the finished scene simply does not work in the film's final cut. In the context of computer animation, storyboarding helps minimize the construction of unnecessary scene components and models, just as it helps live-action filmmakers evaluate what portions of sets need not be constructed because they will never come into the frame.

Often storyboards are animated with simple zooms and pans to simulate camera movement (using non-linear editing software). These animations can be combined with available animatics, sound effects, and dialog to create a presentation of how a film could be shot and cut together. Some feature film DVD special features include production animatics, which may have scratch vocals or may even feature vocals from the actual cast (usually where the scene was cut after the vocal recording phase but before the animation production phase).

Animatics are also used by advertising agencies to create inexpensive test commercials. A variation, the "rip-o-matic", is made from scenes of existing movies, television programs or commercials, to simulate the look and feel of the proposed commercial. Rip, in this sense, refers to ripping-off an original work to create a new one.

Photomatic

[edit]A Photomatic[11] (probably derived from 'animatic' or photo-animation) is a series of still photographs edited together and presented on screen in a sequence. Sound effects, voice-overs, and a soundtrack are added to the piece to show how a film could be shot and cut together. Increasingly used by advertisers and advertising agencies to research the effectiveness of their proposed storyboard before committing to a 'full up' television advertisement.

The Photomatic is usually a research tool, similar to an animatic, in that it represents the work to a test audience so that the commissioners of the work can gauge its effectiveness.

Originally, photographs were taken using a color negative film. A selection would be made from contact sheets and prints made. The prints would be placed on a rostrum and recorded to videotape using a standard video camera. Any moves, pans or zooms would have to be made in-camera. The captured scenes could then be edited.

Digital photography, web access to stock photography and non-linear editing programs have had a marked impact on this way of filmmaking also leading to the term 'digimatic'. Images can be shot and edited very quickly to allow important creative decisions to be made 'live'. Photo composite animations can build intricate scenes that would normally be beyond many test film budgets.

Photomatix was also the trademarked name of many of the booths found in public places which took photographs by coin operation. The Photomatic brand of the booths was manufactured by the International Mutoscope Reel Company of New York City. Earlier versions took only one photo per coin, and later versions of the booths took a series of photos. Many of the booths would produce a strip of four photos in exchange for a coin.

Comic books

[edit]Some writers have used storyboard type drawings (albeit rather sketchy) for their scripting of comic books, often indicating staging of figures, backgrounds, and balloon placement with instructions to the artist as needed often scribbled in the margins and the dialogue or captions indicated. John Stanley and Carl Barks (when he was writing stories for the Junior Woodchuck title) are known to have used this style of scripting.[12][13]

In Japanese comics, the word "name" (ネーム, nēmu, pronounced [neːmɯ]) is used for rough manga storyboards.[14]

Business

[edit]Storyboards used for planning advertising campaigns such as corporate video production, commercials, a proposal or other business presentations intended to convince or compel to action are known as presentation boards. Presentation boards will generally be a higher quality render than shooting boards as they need to convey expression, layout, and mood. Modern ad agencies and marketing professionals will create presentation boards either by hiring a storyboard artist to create hand-drawn illustrated frames or often use sourced photographs to create a loose narrative of the idea they are trying to sell. Storyboards can also be used to visually understand the consumer experience by mapping out the customer's journey brands can better identify potential pain points and anticipate their emerging needs.[15]

Some consulting firms teach the technique to their staff to use during the development of client presentations, frequently employing the "brown paper technique" of taping presentation slides (in sequential versions as changes are made) to a large piece of kraft paper which can be rolled up for easy transport. The initial storyboard may be as simple as slide titles on Post-It notes, which are then replaced with draft presentation slides as they are created.

Storyboards also exist in accounting in the ABC System activity-based costing (ABC) to develop a detailed process flowchart which visually shows all activities and the relationships among activities. They are used in this way to measure the cost of resources consumed, identify and eliminate non-value-added costs, determine the efficiency and effectiveness of all major activities, and identify and evaluate new activities that can improve future performance.

A "quality storyboard" is a tool to help facilitate the introduction of a quality improvement process into an organization.

"Design comics" are a type of storyboard used to include a customer or other characters into a narrative. Design comics are most often used in designing websites or illustrating product-use scenarios during design. Design comics were popularized by Kevin Cheng and Jane Jao in 2006.[16]

Architectural studios

[edit]Occasionally, architectural studios need a storyboard artist to visualize presentations of their projects. Usually, a project needs to be seen by a panel of judges and nowadays it's possible to create virtual models of proposed new buildings, using advanced computer software to simulate lights, settings, and materials. Clearly, this type of work takes time – and so the first stage is a draft in the form of a storyboard, to define the various sequences that will subsequently be computer-animated.[17]

Novels

[edit]Storyboards are now becoming more popular with novelists. Because most novelists write their stories by scenes rather than chapters, storyboards are useful for plotting the story in a sequence of events and rearranging the scenes accordingly.[18]

Interactive media

[edit]More recently the term storyboard has been used in the fields of web development, software development, and instructional design to present and describe, in written, interactive events as well as audio and motion, particularly on user interfaces and electronic pages.

Software

[edit]Storyboarding is used in software development as part of identifying the specifications for a particular set of software. During the specification phase, screens that the software will display are drawn, either on paper or using other specialized software, to illustrate the important steps of the user experience. The storyboard is then modified by the engineers and the client while they decide on their specific needs. The reason why storyboarding is useful during software engineering is that it helps the user understand exactly how the software will work, much better than an abstract description. It is also cheaper to make changes to a storyboard than an implemented piece of software.

An example is the Storyboards system for designing GUI apps for iOS and macOS.[19] Another example is Boords, an online storyboarding software used for planning video projects.[20]

Scientific research

[edit]Storyboards are used in linguistic fieldwork to elicit spoken language.[21] An informant is usually presented with a simplified graphical depiction of a situation or story, and asked to describe the depicted situation, or to re-tell the depicted story. The speech is recorded for linguistic analysis.

Benefits

[edit]One advantage of using storyboards is that it allows (in film and business) the user to experiment with changes in the storyline to evoke stronger reaction or interest. Flashbacks, for instance, are often the result of sorting storyboards out of chronological order to help build suspense and interest.

Another benefit of storyboarding is that the production can plan the movie in advance. In this step, things like the type of camera shot, angle, and blocking of characters are decided.[22]

The process of visual thinking and planning allows a group of people to brainstorm together, placing their ideas on storyboards and then arranging the storyboards on the wall. This fosters more ideas and generates consensus inside the group.

Creation

[edit]

Storyboards for films are created in a multiple-step process. They can be created by hand drawing or digitally on a computer. The main characteristics of a storyboard are:

- Visualize the storytelling.

- Focus the story and the timing in several key frames (very important in animation).

- Define the technical parameters: description of the motion, the camera, the lighting, etc.

If drawing by hand, the first step is to create or download a storyboard template. These look much like a blank comic strip, with space for comments and dialogue. Then sketch a "thumbnail" storyboard. Some directors sketch thumbnails directly in the script margins. These storyboards get their name because they are rough sketches not bigger than a thumbnail. For some motion pictures, thumbnail storyboards are sufficient.

However, some filmmakers rely heavily on the storyboarding process. If a director or producer wishes, more detailed and elaborate storyboard images are created. These can be created by professional storyboard artists by hand on paper or digitally by using 2D storyboarding programs. Some software applications even supply a stable of storyboard-specific images making it possible to quickly create shots that express the director's intent for the story. These boards tend to contain more detailed information than thumbnail storyboards and convey more of the mood for the scene. These are then presented to the project's cinematographer who achieves the director's vision.

Finally, if needed, 3D storyboards are created (called 'technical previsualization'). The advantage of 3D storyboards is they show exactly what the film camera will see using the lenses the film camera will use. The disadvantage of 3D is the amount of time it takes to build and construct the shots. 3D storyboards can be constructed using 3D animation programs or digital puppets within 3D programs. Some programs have a collection of low-resolution 3D figures which can aid in the process. Some 3D applications allow cinematographers to create "technical" storyboards which are optically-correct shots and frames.

While technical storyboards can be helpful, optically-correct storyboards may limit the director's creativity. In classic motion pictures such as Orson Welles' Citizen Kane and Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest, the director created storyboards that were initially thought by cinematographers to be impossible to film.[citation needed] Such innovative and dramatic shots had "impossible" depth of field and angles where there was "no room for the camera" – at least not until creative solutions were found to achieve the ground-breaking shots that the director had envisioned.

See also

[edit]- Filmmaking

- Graphic organizer

- List of film-related topics

- Pre-production

- Screenwriting

- Script breakdown

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Gress, Jon (2015). Visual Effects and Compositing. San Francisco: New Riders. p. 23. ISBN 9780133807240. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Whitehead, Mark (2004). Animation. Pocket Essentials. pp. 47. ISBN 9781903047460.

- ^ 'The Story of Walt Disney' (Henry Holt, 1956)

- ^ Finch, Christopher (1995). The Art of Walt Disney : From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdoms. New York: Harry N. Abrams Incorporated. p. 64. ISBN 0-8109-1962-1.

- ^ Lee, Newton; Krystina Madej (2012). Disney Stories: Getting to Digital. London: Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9781461421016.

- ^ Krasniewicz, Louise (2010). Walt Disney: A Biography. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. pp. 60–64. ISBN 9780313358302.

- ^ Gabler, Neal (2007). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 181–189. ISBN 9780679757474.

- ^ 1936 documentary Cartoonland Mysteries

- ^ a b Katz, Steven D. (1991). Film Directing Shot by Shot: Visualizing from Concept to Screen. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions. p. 103. ISBN 9780941188104. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ "Director's Storyboard". Pinecrest Players Theatre. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ "Centrum Man / Woman". www.animaticmedia.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ^ Carl Barks: Conversations, p. 41, at Google Books

- ^ John Stanley: Giving Life to Little Lulu, p. 36, at Google Books

- ^ How to Draw Manga: Putting Things in Perspective, p. 110, at Google Books

- ^ Editorial, Inc (2022-01-07). "Adapt to What Work Looks Like Now". Inc.com. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ 2006 Information Architecture Summit wrapup, boxesandarrows.com, 19 April 2006

- ^ Cristiano, Giuseppe (2008). The Storyboard Design Course. London UK: Thames&Hudson. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-500-28690-6.

- ^ "How to Storyboard a Novel (Step-by-Step Guide) | Boords". boords.com. 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ "Xcode Overview: Designing with Storyboards". developer.apple.com. Apple.com. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ "Boords - Online Storyboard & Animatic Software". boords.com. Retrieved 2023-09-02.

- ^ Strang Burton and Lisa Matthewson. "Targeted construction storyboards in semantic fieldwork". In: Ryan Bochnak and Lisa Matthewson, editors, Methodologies in Semantic Fieldwork, 135–156. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- ^ "Storyboarding Basics - Infographic Guide for Film, TV and Animation". jugaadanimation.com. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

General references

[edit]- Halligan, Fionnuala (2013). Movie Storyboards: The Art of Visualizing Screenplays. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 9781452122199. OCLC 1089341414.

External links

[edit] Media related to Storyboards at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Storyboards at Wikimedia Commons