Deana Lawson

Deana Lawson | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1979 (age 45–46) Rochester, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Rhode Island School of Design, Pennsylvania State University |

| Known for | Photography |

| Awards | Hugo Boss Prize 2020 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2022 |

Deana Lawson (born 1979) is an American artist, educator, and photographer based in Brooklyn, New York.[1] Her work is primarily concerned with intimacy, family, spirituality, sexuality, and Black aesthetics.

Lawson has been praised for her ability to communicate the nuances of African American experience: "Lawson's oeuvre explores intimacy, affinity, sexuality and relationships.[2] She has work held in the International Center for Photography collections. Her photographs have been exhibited in a number of museums and galleries including the Museum of Modern Art,[3] Whitney Museum of American Art,[4] and the Art Institute of Chicago.

A solo exhibition of her work, The Hugo Boss Prize 2020: Deana Lawson, Centropy is on view May 7-October 11, 2021 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.[5]

Early life and education

[edit]Lawson was born in 1979 in Rochester, New York.[6][7] She received her B.F.A. in 2001 in photography from Pennsylvania State University, and her M.F.A. in photography from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 2004.[6] Regarding her second year at Penn State, Lawson said, "I reached an early crossroads—either I was going to continue with a business degree or I was going to jump off that moving train and become an artist. I jumped and never looked back."[8]

Teaching

[edit]Lawson was an assistant professor of Photography at Princeton University in Princeton, New Jersey beginning in 2012.[9] In 2021, she was named the inaugural Dorothy Krauklis '78 Professor of Visual Arts in Princeton University's Lewis Center for the Arts.[10] She has also taught at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), International Center for Photography, California College of the Arts (CCA), and Rhode Island School of Design.[9]

Work

[edit]

Lawson credits her interest in taking photographs to African American photographers like Carrie Mae Weems and Renee Cox.[11] During her undergraduate years, Lawson was shocked at the lack of scholarship surrounding photographers of color. This led her to learn more about black artists, like Lorna Simpson, whose work inspired her to pursue photography as a medium: "Just to have that model--to realize that not only did I like to make pictures but that I could actually do this, you know, was absolutely important to reaffirm myself as an artist".[11]

Lawson's highly formalist photographs are distinguishable by their meticulous staging, intimate composition, and attention to black cultural symbols. Her photos are highly staged, with an emphasis on "the strangely potent components of black interiors".[12] While referring to her subjects as "family", her models are more often than not strangers she meets randomly in public spaces.[3] In an artist statement, Lawson writes: "My work negotiates a knowledge of selfhood through a profoundly corporeal dimension; the photographs speaking to the ways that sexuality, violence, family, and social status may be written, sometimes literally, upon the body."[13]

In 2011, The New Yorker's Jessie Wender described Lawson's portraits as "intimate and unexpected".[14] In Wender's interview with Lawson, the photographer discussed her inspirations, including "vintage nudes, Sun Ra, Nostrand Ave., sexy mothers, juke joints, cousins, leather bound family albums, gnarled wigs, Dana Lawson [her sister], the color purple, The Grizzly Man, M.J., oval portraits, Arthur Jafa, thrift shops, Breakfast at Tiffany's, acrylic nails, weaves on pavement, Aaron Gilbert [her former husband], the A train, Tell My Horse, typewriters, Notorious B.I.G., fried fish, and lace curtains".[14] Formally, Lawson said, "Formally the images are unified by a clear directorial voice. The subject's pose, lighting, and environment are all carefully considered."[14]

Lawson has stated that her most challenging or successful work is The Garden, which references the Eden scene in Hieronymus Bosch's painting The Garden of Earthly Delights.[8] In 2014 Lawson traveled to Congo to look for references for her vision of Eden, and this journey led her to the small village called Gemena, which became the setting for The Garden.[8]

While many of Lawson's photographs are taken in New York, she has also photographed subjects in Louisiana, Haiti, Jamaica, Ethiopia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[15] She has expressed the hope that through travel, her work can reflect the ways in which black culture is not confined by physical boundaries.[15]

In November 2015, Lawson was commissioned by Time to photograph the aftermath of the Charleston church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina by mass murderer Dylann Roof.[16] Steven Nelson, Dean of the Center for Advanced Study in the Arts at the National Gallery of Art, observes that although the photographs document the aftermath rather than the massacre itself, her journalistic photographs for Time nonetheless "dovetail with images that have depicted violence against black people."[2]

In 2016, Lawson's photograph, Binky & Tony Forever, was used as the cover art for Freetown Sound, the third album by Dev Hynes for Blood Orange.[17] The photograph is set in Lawson's bedroom and depicts young love, with an emphasis on the female figure—"the female gaze, and her space, and her love", in Lawson's words.[17]

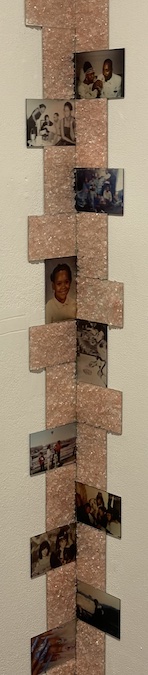

Lawson's large scale photography, Ring Bearer[18] (2016) was featured in the 2017 Whitney Biennial.[19] The movie Queen & Slim (2019) was inspired by Lawson's photography, in capturing an intimate portrayal of black experience and the stylized home interiors.[20][21][22] In 2019, Lawson photographed Melina Matsoukas, the director of the film.[23] Lawson was included in the 2019 traveling exhibition Young, Gifted, and Black: The Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art.[24] Lawson's first full-scale museum survey was organized in 2021 by the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston and traveled to MoMA PS1. The show included assemblages created by the artist with crystals in addition to photographs.[25]

Personal life

[edit]Lawson has two children with her former husband, artist Aaron Gilbert.[11][26]

Publications

[edit]- Deana Lawson. Edited by Peter Eleey & Eva Respini. London: Mack, 2021. ISBN 978-1-912339-98-3. Includes essays by Eva Respini and Peter Eleey, Kimberly Juanita Brown, Tina Campt, Alexander Nemerov, Greg Tate, and a conversation between Lawson and Deborah Willis. Accompanies an exhibition at ICA/Boston, 2021/22; MoMA PS1, 2022; and High Museum of Art, 2022/23.

Awards

[edit]- 2008–2009: Aaron Siskind Foundation, Individual Photographer's Fellowship grant[27]

- 2013: Guggenheim Fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for her work in photography[1]

- 2020: Hugo Boss Prize by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum[28][29]

- 2022: Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2022, the Photographers' Gallery, London[30][31]

Exhibitions

[edit]Solo exhibitions

[edit]- 2014 Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, Deana Lawson: Mother Tongue[32]

- 2017 Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, Deana Lawson[33]

- 2018 Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, New Work[34]

- 2018 Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Forum 80: Deana Lawson[35]

- 2018–2019 The Underground Museum, Los Angeles, Deana Lawson: Planes[36]

- 2020 Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland, Deana Lawson: Centropy[37]

- 2021 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, The Hugo Boss Prize 2020: Deana Lawson, Centropy[5]

Group exhibitions

[edit]- 2016 The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, Black Cowboy[38]

- 2017 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, New York, United States, The 2017 Whitney Biennial[39]

- 2018 Gordon Parks Foundation, New York, American Family: Derrick Adams and Deana Lawson[40]

- 2018 Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, Rhode Island, The Phantom of Liberty[41]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Deana Lawson". John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ a b Nelson, Steven (June 4, 2018). "Issues of Intimacy, Distance, and Disavowal in Writing About Deana Lawson's Work". Hyperallergic. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ a b "New Photography 2011, Deana Lawson". MoMA. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ "Deana Lawson (American, 1979)". mutualart.com. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ a b "The Hugo Boss Prize 2020: Deana Lawson, Centropy". The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation. Retrieved 2021-04-16.

- ^ a b "Profile". Princeton University. Archived from the original on 2017-05-04. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ Great women artists. Phaidon Press. 2019. p. 235. ISBN 978-0714878775.

- ^ a b c "Deana Lawson". Interview. 2015-12-02. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- ^ a b "Deana Lawson". Princeton, Lewis Center for the Arts. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ "Professor of Visual Arts Deana Lawson Wins Prestigious 2020 Hugo Boss Prize". Lewis Center for the Arts. 2020-10-22. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ^ a b c "In Conversation with Deana Lawson". Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art. 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ St. Félix, Doreen (2018-03-12). "Deana Lawson's Hyper-Staged Portraits of Black Love". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ "Deana Lawson – CPW". www.cpw.org. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ a b c "Deana Lawson's Intimate Strangers". The New Yorker. 2011-12-15. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ a b "Deana Lawson: Ruttenberg Contemporary Photography Series". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2015. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ Laurent, Olivier (2015-11-11). "Telling Charleston's Story in Photographs". Time. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ a b "The True Story Behind The Cover Of Blood Orange's Freetown Sound". The Fader. 28 June 2016. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- ^ "The Cutting-Edge Sincerity of the Whitney Biennial". The New Republic. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ^ Livingstone, Josephine (2017-03-16). "The Cutting Edge Sincerity of the Whitney Biennial". New Republic. Retrieved 2017-05-10.

- ^ "Forward 50 | Melina Matsoukas: The camera queen". The Forward. 2019-12-20. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ Ugwu, Reggie (2019-11-01). "With 'Queen & Slim,' Melina Matsoukas Steps Beyond Beyoncé". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ "From Beyoncé to the big screen: the whirlwind rise of Melina Matsoukas". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ "Melina Matsoukas' 'Queen & Slim' is redefining Hollywood". The California Sunday Magazine. 2019-11-18. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ Sargent, Antwaun (2020). Young, gifted and Black : a new generation of artists : Lumpkin-Boccuzzi Family Collection of Contemporary Art. New York, NY: D.A.P. pp. 128–131. ISBN 9781942884590.

- ^ "Deana Lawson Checklist" (PDF). MoMA PS1. Museum of Modern Art. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Lubow, Arthur (2018-10-11). "Deana Lawson Reveals Hidden Grandeur in Her Uncanny Portraits". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ^ "IPF Grant Recipients". Aaron Siskind Foundation. 2017. Archived from the original on 2020-07-01.

- ^ "Deana Lawson Awarded Hugo Boss Prize 2020". Guggenheim.

- ^ Gaskin, Sam (22 October 2020). "Who Won the $100,000 Hugo Boss Prize?". Ocula.

- ^ Khomami, Nadia; Arts, Nadia Khomami; correspondent, culture (12 May 2022). "Artist who 'reclaims black experience' wins Deutsche Börse photography prize". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

{{cite news}}:|last3=has generic name (help) - ^ Warner, Marigold. "Deana Lawson wins the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2022". British Journal of Photography. Retrieved 2023-07-08.

- ^ "Deana Lawson: Mother Tongue | Rhona Hoffman Gallery | Artsy". www.artsy.net. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ "Deana Lawson | Rhona Hoffman Gallery | Artsy". www.artsy.net. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ "New Work | Sikkema Jenkins & Co. | Artsy". www.artsy.net. Archived from the original on 2022-05-14. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ "Deana Lawson". Carnegie Museum of Art. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ^ "The Underground Museum". theunderground-museum.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-11. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ^ "Exhibition Deana Lawson: Centropy". contemporaryand.com. 2020-06-09. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ "Black Cowboy | The Studio Museum in Harlem | Artsy". www.artsy.net. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ "List of Artists Announced for 2017 Whitney Biennial | artnet News". artnet News. 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ "American Family: Derrick Adams and Deana Lawson - Exhibitions - The Gordon Parks Foundation". www.gordonparksfoundation.org. Retrieved 2019-03-09.

- ^ "Binky and Tony Forever | RISD Museum". risdmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-03-13.

External links

[edit]- Living people

- 1979 births

- Princeton University faculty

- Rhode Island School of Design alumni

- Penn State College of Arts and Architecture alumni

- Artists from Rochester, New York

- African-American contemporary artists

- American contemporary artists

- Photographers from New York (state)

- 21st-century American photographers

- 21st-century American women photographers

- African-American photographers

- 21st-century African-American academics

- 21st-century American academics

- African-American women academics

- American women academics

- 21st-century African-American women

- 21st-century African-American artists

- 20th-century African-American academics

- 20th-century American academics

- 20th-century African-American women

- Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize winners