Dean Kamen

Dean Kamen | |

|---|---|

Kamen at Whiteman Air Force Base on April 26, 2016 | |

| Born | Dean Lawrence Kamen April 5, 1951[1] |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Invention of the iBot Wheelchair, the Segway and founder of FIRST North Dumpling Island |

| Awards | Hoover Medal (1995) Heinz Award in Technology, the Economy and Employment (1999) |

Dean Lawrence Kamen (/ˈkeɪmɪn/; born April 5, 1951) is an American engineer, inventor, and businessman. He is known for his invention of the Segway and iBOT,[2] as well as founding the non-profit organization FIRST with Woodie Flowers.[3][4] Kamen holds over 1,000 patents.[5]

Early life and family

[edit]Kamen was born on Long Island, New York, to a Jewish family.[6] His father was Jack Kamen, an illustrator for Mad, Weird Science and other EC Comics publications. During his teenage years, Kamen was already being paid for his ideas; local bands and museums paid him to build light and sound systems. His annual earnings reached $60,000 before his high school graduation.[2]

He attended Worcester Polytechnic Institute, but in 1976[7] quit before graduating, after five years of private advanced research for the insulin pump AutoSyringe.[8][9]

Career

[edit]

Inventions

[edit]Kamen is known best for inventing the product that eventually became known as the Segway PT, an electric, self-balancing human transporter with a computer-controlled gyroscopic stabilization and control system. The device is balanced on two parallel wheels and is controlled by moving body weight. The machine's development was the object of much speculation and hype after segments of a book quoting Steve Jobs and other notable information technology visionaries espousing its society-revolutionizing potential were leaked in December 2001.[10]

Kamen was already a successful inventor: his company Auto Syringe manufactures and markets the first drug infusion pump.[11]: 13 His company DEKA also holds patents for the technology used in portable dialysis machines, an insulin pump (based on the drug infusion pump technology),[11]: 19 and an all-terrain electric wheelchair known as the iBOT, using many of the same gyroscopic balancing technologies that later made their way into the Segway.

Kamen has worked extensively on a project involving Stirling engine designs, attempting to create two machines: one that would generate power, and the Slingshot[12] that would serve as a water purification system.[13] He hopes the project will help improve living standards in developing countries.[14][15] Kamen has a patent on his water purifier,[16] and other patents pending. In 2014, the film SlingShot was released, detailing Kamen's quest to use his vapor compression distiller to fix the world's water crisis.[17]

Kamen is also the co-inventor of a compressed air device that would launch a human into the air in order to quickly launch SWAT teams or other emergency workers to the roofs of tall, inaccessible buildings.[18][19]

In 2009 Kamen stated that his company DEKA was now working on solar powered inventions.[15]

Kamen and DEKA also developed the DEKA Arm System or "Luke", a prosthetic arm replacement that offers its user much more fine motor control than traditional prosthetic limbs. It was approved for use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in May 2014, and DEKA is looking for partners to mass-produce the prosthesis.[20]

FIRST

[edit]In 1989, Kamen founded FIRST (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology), an organization intended to build students' interests in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). In 1992, working with MIT Professor Emeritus Woodie Flowers, Kamen created the FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC), which evolved into an international competition that by 2020 had drawn 3,647 teams and more than 91,000 students.[21][4][22]

FIRST organizes robotics competition leagues for students in grades K-12, including FIRST LEGO League Discover for ages 4–6, FIRST LEGO League Explore for younger elementary school students, FIRST LEGO League Challenge for older elementary school and middle school students, FIRST Tech Challenge (FTC) for middle and high school students, and FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC) for high school students.[23] In 2017, FIRST held its first Olympics-style competition – FGC (FIRST Global Challenge) – in Washington, D.C.

In 2010, Kamen called FIRST the invention he is most proud of, and said that 1 million students had taken part in the contests.[24]

Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute

[edit]In 2017, Kamen founded the Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute (ARMI)[25] and launched BioFabUSA,[26] a Manufacturing USA Innovation Institute with an $80 million grant from the Department of Defense. BioFabUSA's mission is to "...make practical the large-scale manufacturing of engineered tissues and tissue-related technologies, to benefit existing industries and grow new ones"[25] In addition to DoD funding, Kamen brought together a consortium of private sector entities to form a public-private partnership which pledged $214M additional private dollars.[27]

In early 2020, ARMI was awarded a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services to establish the first Foundry for American Biotechnology,[28] known as NextFab[29] "to produce technological solutions that help the United States protect against and respond to health security threats, enhance daily medical care, and add to the U.S. bioeconomy".[28][30]

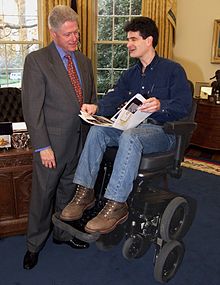

Awards

[edit]Kamen has won numerous awards. He was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 1997 for inventing and commercializing biomedical devices and fluid measurement and control systems, and for popularizing engineering among young people. In 1999 he was awarded the 5th Annual Heinz Award in Technology, the Economy and Employment,[31] and in 2000 received the National Medal of Technology from then President Clinton for inventions that have advanced medical care worldwide. In April 2002, Kamen was awarded the Lemelson-MIT Prize for inventors, for his invention of the Segway and of an infusion pump for diabetics. In 2003 his "Project Slingshot", an inexpensive portable water purification system, was named a runner-up for "coolest invention of 2003" by Time magazine.[32]

In 2005 he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for his invention of the AutoSyringe. In 2006 Kamen was awarded the "Global Humanitarian Action Award" by the United Nations. In 2007 he received the ASME Medal, the highest award from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers,[33] in 2008 he was the recipient of the IRI Achievement Award from the Industrial Research Institute,[34] and in 2011 Kamen was awarded the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Mechanical Engineering of the Franklin Institute.[35]

Kamen received an honorary Doctor of Engineering degree from Worcester Polytechnic Institute in 1992,[36] Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute May 17, 1996,[37] a Doctor of Engineering degree from Kettering University in 2001,[citation needed] an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Clarkson University on May 13, 2001,[citation needed] an honorary "Doctor of Science" degree from the University of Arizona on May 16, 2009,[citation needed] and an honorary doctorate from the Wentworth Institute of Technology when he spoke at the college's centennial celebration in 2004,[citation needed] and other honorary doctorates from North Carolina State University in 2005,[citation needed] Bates College in 2007,[38] the Georgia Institute of Technology in 2008,[39] the Illinois Institute of Technology in 2008[citation needed] the Plymouth State University in May 2008[citation needed] and Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in 2012.[40] In 2015, Kamen received an honorary Doctor of Engineering and Technology degree from Yale University.[41] In 2017, Kamen was honored with an institutional honorary degree from Université de Sherbrooke.[42]

Kamen received the Stevens Honor Award on November 6, 2009, given by the Stevens Institute of Technology and the Stevens Alumni Association.[43] On November 14, 2013, he received the James C. Morgan Global Humanitarian Award.[44]

Kamen received the 2018 Public Service Award from the National Science Board, honoring his exemplary public service and contributions to the public's understanding of science and engineering.[45]

Trivia

[edit]

In 2007, his residence was a hexagonal, shed style mansion he dubbed Westwind,[14] located in Bedford, New Hampshire, just outside Manchester. The house has at least four levels and is very eclectically conceived, with such things as: hallways resembling mine shafts; 1960s novelty furniture; a collection of vintage wheelchairs; spiral staircases; at least one secret passage; an observation tower; a fully equipped machine shop; and a huge cast iron steam engine which once belonged to Henry Ford (built into the multi-story center atrium of the house) which Kamen is working to convert into a Stirling engine-powered kinetic sculpture.[citation needed] Kamen owns and pilots an Embraer Phenom 300 light jet aircraft[46] and three Enstrom helicopters, including a 280FX, a 480, and a 480B.[47][48][49] He regularly commutes to work via his helicopters and had a hangar built into his house.[50] In 2016 he flew as a passenger in a B-2 Spirit bomber at Whiteman AFB, marking the opening of the 2016 FRC World Championship in St. Louis.[51]

He is the main subject of Code Name Ginger: the Story Behind Segway and Dean Kamen's Quest to Invent a New World, a nonfiction narrative book by journalist Steve Kemper published by Harvard Business School Press in 2003 (released in paperback as Reinventing the Wheel).[11]

His company, DEKA, annually creates intricate mechanical presents for him. The company has created a robotic chess player, which is a mechanical arm attached to a chess board, and a vintage-looking computer with antique wood, and a converted typewriter as a keyboard. In addition, DEKA has received funding from DARPA to work on a brain-controlled prosthetic limb called the Luke Arm.[52]

Kamen is a member of the USA Science and Engineering Festival's Advisory Board[53] and is also a member of the Xconomists, an ad hoc team of editorial advisors for the tech news and media company, Xconomy.[54] He is also on the Board of Trustees of the X Prize Foundation.

Dean of Invention, a TV show on Planet Green, premiered on October 22, 2010. It starred Kamen and correspondent Joanne Colan, in which they investigate new technologies,[55]

Kamen was a keynote speaker at the 2015 Congress of Future Science and Technology Leaders.[56]

In the 2016 United States Senate election in New Hampshire, Kamen endorsed Kelly Ayotte, appearing in an ad supporting her. [57]

See also

[edit]Index

[edit]- ^ a b "Dean Kamen". Lemelson–MIT Prize. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ a b "Dean Kamen | Biography, Pictures and Facts". Famous Entrepreneurs. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Longley, Robert. "Biography of Dean Kamen, American Engineer and Inventor".

- ^ a b Cullinane, Maeve. "Afterhours with Woodie Flowers". The Tech. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Dean Kamen Doesn't Have 450 Patents (He Has Way More)". PCMAG. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Kraft, Dina (April 24, 2008). "Segway inventor Dean Kamen brings his high-tech vision to Israel". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "Pure Genius: How Dean Kamen's Invention Could Bring Clean Water To Millions | Richard Dawkins Foundation". www.richarddawkins.net. June 17, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ "AutoSyringe". freepatentsonline.com. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ "$500,000 Lemelson-MIT Prize Awarded To Dean Kamen". mit.edu. Massachusetts Institute of Technology School of Engineering. Archived from the original on March 6, 2003. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ Heilemann, John (December 2, 2001). "Reinventing the Wheel". Time. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c Kemper, Steve (2003). Code Name Ginger: the story behind Segway and Dean Kamen's quest to invent a new world. Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 1-57851-673-0.

- ^ "Pure Genius: How Dean Kamen's Invention Could Bring Clean Water To Millions". Popular Science. June 16, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- ^ Whitesides, Loretta Hidalgo (March 25, 2008). "Colbert and Kamen Solve the World's Water Problems". WIRED. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Kirsner, Scott (January 9, 2000). "Breakout Artist". WIRED. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Harris, Mark (July 22, 2009). "Segway inventor on future technology". The Guardian. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ U.S. patent 7,340,879

- ^ "About|SlingShot". slingshotdoc.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ Williams, Chris (May 16, 2006). "DARPA plots emergency man-cannon". The Register. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ US Patent Application No. 20060086349

- ^ Lawler, Richard (September 5, 2014). "FDA approves a life-like prosthetic arm from the man who invented the Segway". Engadget. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ Stone 2007, pp. 204–205.

- ^ "2020 Season Facts" (PDF). FIRST. January 2, 2020.

- ^ FIRST Official Website Archived October 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine – accessed December 23, 2009

- ^ Harris, Mark (June 10, 2010). "Brain scan: Mr Segway's difficult path". The Economist. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ a b "Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute". Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "BioFabUSA". Manufacturing USA. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "DOD-funded Advanced Regenerative Manufacturing Institute opens its doors to the future". www.army.mil. August 24, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ a b "HHS Pioneers First Foundry for American Biotechnology". HHS.gov. February 10, 2020. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "First Foundry for American Biotechnology Launched in New Hampshire | Governor Christopher T. Sununu". www.governor.nh.gov. Retrieved April 16, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Bookman, Todd (November 19, 2023). "Dean Kamen's private companies reap millions from the federally funded nonprofit he runs". New Hampshire Public Radio. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Dean Kamen". heinzawards.net. The Heinz Awards.

- ^ "The Gartner Fellows: Dean Kamen Interview". Gartner.com. October 30, 2003. Archived from the original on December 21, 2003. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ^ "ASME Medal". American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ "Dean Kamen Honored with IRI 2008 Achievement Award". Industrial Research Institute. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2012.Add'l archive URLs as primary is glitchy and numeric IP-based: , https://archive.today/20130503043538/http://www.iriweb.org/Main/About_IRI/IRI_Awards/IRI_Achievement_Award/

- ^ "Benjamin Franklin Medal in Mechanical Engineering". Franklin Institute. 2011. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2011.

- ^ "Symposium Keynote". wpi.edu. Worcester Polytechnic Institute. March 3, 2017. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "Commencement Speakers & Honorary Degree Recipients | Institute Archives and Special Collections". archives.rpi.edu. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ^ "Citation for Dean Kamen". Bates College. April 26, 2010. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Two Hundredth And Thirtieth Commencement Exercise" (PDF). Georgia Institute of Technology. May 3, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ "Graduation 'responsibility': Rose-Hulman stages 134th commencement exercises". Tribune Star. May 27, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "Yale awards nine honorary degrees at Commencement 2015". Yale University. May 15, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ "La 58e promotion et Dean Kamen à l'honneur" (in French). Université de Sherbrooke. September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "The Heinz Awards :: Dean Kamen receives the Stevens Honor Award". www.heinzawards.net. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ "Pioneering health-care technologist Dean Kamen named 2013 James C. Morgan Global Humanitarian Award recipient". TheTech.org. The Tech Museum of Innovation. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- ^ "National Science Board". National Science Board. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- ^ "N-Number Inquiry Results". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ "N-Number Inquiry Results". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ "N-Number Inquiry Results". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ "N-Number Inquiry Results". Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ Iconoclasts, Season 2, Show #10. Isabella Rossellini and Dean Kamen, November 16, 2006.

- ^ "FIRST founder, Dean Kamen, flies in B-2 Spirit At Whiteman AFB maintained by FIRST alumni". businesswire.com. April 26, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ^ "New Luke Arm Video". Medgadget.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ^ "Advisors". usasciencefestival.org. USA Science and Engineering Festival. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2015. retrieved July 5, 2010

- ^ "About Our Mission, Team, and Editorial Ethics". Xconomy.com. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ "About Dean Of Invention: A New Show Dedicated To The World's Greatest Scientific Breakthroughs Of Today". planetgreen.discovery.com.

- ^ "Speaker Lineup Confirmed for Congress of Future Scientists and Technologists". PRWeb. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ ""One of Us" | Kelly Ayotte | New Hampshire". YouTube.

Works cited

[edit]- Stone, Brad (2007). Gearheads: The Turbulent Rise of Robotic Sports. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-8732-3.

External links

[edit]- Dean Kamen at IMDb

- Dean Kamen at TED

- 1951 births

- American inventors

- 20th-century American Jews

- American mechanical engineers

- American technology chief executives

- American technology company founders

- American transhumanists

- ASME Medal recipients

- Fellows of the American Institute for Medical and Biological Engineering

- For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology

- Henry Laurence Gantt Medal recipients

- Jewish engineers

- Lemelson–MIT Prize

- Living people

- Members of the United States National Academy of Engineering

- Micronational leaders

- National Medal of Technology recipients

- People from Bedford, New Hampshire

- People from Long Island

- Sustainable transport pioneers

- Worcester Polytechnic Institute alumni

- 21st-century American Jews

- Benjamin Franklin Medal (Franklin Institute) laureates