Cultural depictions of bears

Bears have been depicted throughout history by many different cultures and societies. Bears are very popular animals that feature in many stories, folklores, mythology and legends from across the world, ranging from North America, Europe and Asia. In the 20th century bears have been very popular in pop culture with several high profile characters and stories with depictions of bears e.g. Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Rupert Bear, Paddington Bear and Winnie the Pooh.

Religion, folklore and mythology

[edit]

There is evidence of prehistoric bear worship, though archaeologists dispute the details.[1] It is possible that bear worship existed in early Chinese and Ainu cultures.[2] The prehistoric Finns,[3] Siberian peoples[4] and more recently Koreans considered the bear as the spirit of their forefathers.[5][need quotation to verify] In many Native American cultures the bear symbolizes rebirth because of its hibernation and re-emergence.[6] The image of the mother bear was prevalent throughout societies in North America and Eurasia, based on the female's devotion to and protection of her cubs.[7] Japanese folklore features the Onikuma, a "demon bear" that walks upright.[8] The Ainu of northern Japan, as ethnically distinct from the Japanese, saw the bear instead as sacred; Hirasawa Byozan painted a scene in documentary style of a bear sacrifice in an Ainu temple, complete with offerings to the dead animal's spirit.[9]

In Korean mythology, a tiger and a bear prayed to Hwanung, the son of the Lord of Heaven, that they might become human. Upon hearing their prayers, Hwanung gave them 20 cloves of garlic and a bundle of mugwort, ordering them to eat only this sacred food and to remain out of the sunlight for 100 days. The tiger gave up after about twenty days and left the cave. However, the bear persevered and was transformed into a woman. The bear and the tiger are said[by whom?] to represent two tribes that sought the favor of the heavenly prince.[10] The bear-woman (Ungnyeo; 웅녀/熊女) was grateful and made offerings to Hwanung. However, she lacked a husband, and soon became sad and prayed beneath a "divine birch" tree (Korean: 신단수; Hanja: 神檀樹; RR: sindansu) to be blessed with a child. Hwanung, moved by her prayers, took her for his wife and soon she gave birth to a son named Dangun Wanggeom – who was the legendary founder of Gojoseon, the first ever Korean kingdom.[11]

Artio (Dea Artio in the Gallo-Roman religion) was a Celtic bear-goddess. Evidence of her worship has notably been found at Bern, itself named for the bear. Her name is derived from the Celtic word for "bear", artos.[12] In ancient Greece, the archaic cult of Artemis in bear form survived into Classical times at Brauron, where young Athenian girls passed an initiation right as arktai "she bears".[13] For Artemis and one of her nymphs as a she-bear, see the myth of Callisto.

In pagan myths of the Russian lands the bear was considered to be a mystical master/owner of forests. Consequently the original Indo-European name for such mystical heavyweights became taboo, and Russian speakers came to use the euphemism medved (Russian: медведь), literally meaning "honey-eater".[14] In post-Christian Russian folklore, the bear often appears semi-anthropomorphized as Mikhailo Ivanovich, or even more familiarly as Misha.[15] Mikhailo Ivanovich, though respected for his strength, often falls victim to tricks and cunning ploys, planned (for example) by a fox.

Bears are mentioned in the Bible: the Second Book of Kings relates the story of the prophet Elisha calling on them to eat the youths who taunted him.[16] Legends of saints taming bears are common in the Alpine zone. In the coat of arms of the bishopric of Freising, the bear is the dangerous totem animal tamed by St. Corbinian and made to carry his civilized[clarification needed] baggage over the mountains. Bears similarly feature in the legends of St. Romedius, Saint Gall and Saint Columbanus. This church used this recurrent motif as a symbol of the victory of Christianity over paganism.[17] In the Norse settlements of northern England during the 10th century, a type of "hogback" grave-cover of a long narrow block of stone, with a shaped apex like the roof beam of a long house, is carved with a muzzled (and thus Christianized) bear clasping each gable end, as in the church at Brompton, North Yorkshire and across the British Isles.[18]

Lāčplēsis, meaning "Bear-slayer", is a Latvian legendary hero who is said to have killed a bear by ripping its jaws apart with his bare hands. However, as revealed in the end of the long epic describing his life, Lāčplēsis' own mother had been a she-bear, and his superhuman strength resided in his bear ears. The modern Latvian military award Order of Lāčplēsis, named for the hero, is also known as The Order of the Bear-Slayer.[citation needed]

In the Hindu epic poem The Ramayana, the sloth bear or Asian black bear Jambavan is depicted as the king of bears and helps the title-hero Rama defeat the epic's antagonist Ravana and reunite with his queen Sita.[19][20]

In French folklore, Jean de l'Ours is a hero born half-bear, half-human. He obtains a weapon, usually a heavy iron cane, and on his journey, bands up with two or three companions. At a castle the hero defeats an adversary, pursues him to a hole, discovers an underworld, and rescues three princesses. The companions abandon him in the hole, taking the princesses for themselves. The hero escapes, finds the companions and gets rid of them. He marries the most beautiful princess of the three, but not before going through certain ordeal(s) set by the king.[21]

National and regional symbolism

[edit]

Bears, like other animals, may symbolize nations. The Eurasian brown bear has been used to personify Russia since the early 19th century.[22] In 1911, the British satirical magazine Punch published a cartoon about the Anglo-Russian Entente by Leonard Raven-Hill in which the British lion watches as the Russian bear sits on the tail of the Persian cat.[23] The Russian Bear has been a common national personification for Russia from the 16th century onward.[24] Smokey Bear has become a part of American culture since his introduction in 1944, with his message "Only you can prevent forest fires".[25] In the United Kingdom, the bear and staff feature on the heraldic arms of the county of Warwickshire.[26] Bears appear in the canting arms of two cities, Bern and Berlin.[27]

In Finland, the brown bear, which is also nicknamed as the "king of the forest" by the Finns,[28][29] is even so common that it is the country's official national mammal,[30] and occur on the coat of arms of the Satakunta region is a crown-headed black bear carrying a sword,[31] possibly referring to the regional capital city of Pori, whose Swedish name Björneborg and the Latin name Arctopolis literally means "bear city" or "bear fortress".[32]

In Madrid, Spain, the east side of the Puerta del Sol has the Statue of the Bear and the Strawberry Tree, the statue is created by sculptor Antonio Navarro Santafé and inaugurated on 19 January 1967.[33] It presents a bear supports his paws on the strawberry tree and directs his attention towards one of the fruits, represents in a real-life form the coat of arms of Madrid.

Literature and media

[edit]Bears are popular in children's stories, including Winnie the Pooh,[34] Paddington Bear,[35] Gentle Ben[36] and The Brown Bear of Norway.[37] An early version of Goldilocks and the Three Bears,[38] was originally published as The Three Bears in 1837 by Robert Southey, many times retold, and illustrated in 1918 by Arthur Rackham.[39] In a continuation of the anthropomorphic themes of Goldilocks are the Berenstain Bears, which behave and act like a human family.

Teddy Bears' Picnic remains a popular children's song. In fact, bears are frequently depicted in children's media as cuddly and friendly companions, such as the depiction of Baloo in Disney's version of The Jungle Book.

The Hanna-Barbera character Yogi Bear has appeared in numerous comic books, animated television shows and films.[40][41] The Care Bears began as greeting cards in 1982, and were featured as toys, on clothing and in film.[42] Around the world, many children—and some adults—have teddy bears, stuffed toys in the form of bears, named after the American statesman Theodore Roosevelt when in 1902 he had refused to shoot an American black bear tied to a tree.[43]

In both Brave and Brother Bear, the bears depicted are used as a supernatural story telling device – the bears in the two movies swap bodies with a human character in order to teach them a lesson about familial bonds.

In the TTRPG Dungeons & Dragons, bears have become a species of fish with the advent of 5th edition. This is because the trident of fish command says it works on any beast with an innate swimming speed which includes several bears within the edition.[44]

Cosmology

[edit]

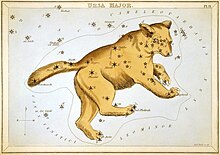

The constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the great and little bears, are named for their supposed resemblance to bears, from the time of Ptolemy.[a][46] The nearby star Arcturus means "guardian of the bear", as if it were watching the two constellations.[47] Ursa Major has been associated with a bear for as much as 13,000 years since Paleolithic times, in the widespread Cosmic Hunt myths. These are found on both sides of the Bering land bridge, which was lost to the sea some 11,000 years ago.[48]

Berserkers – bear warriors

[edit]It is proposed by some authors that the Old Norse warriors, the berserkers, drew their power from the bear and were devoted to the bear cult, which was once widespread across the northern hemisphere.[49] [50] The berserkers maintained their religious observances despite their fighting prowess, as the Svarfdæla saga tells of a challenge to single-combat that was postponed by a berserker until three days after Yule.[51] The bodies of dead berserkers were laid out in bearskins prior to their funeral rites.[52] The bear-warrior symbolism survives to this day in the form of the bearskin caps worn by the guards of the Danish monarchs.[51]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wunn, Ina (2000). "Beginning of Religion". Numen. 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612. S2CID 53595088.

- ^ Kindaichi, Kyōsuke; Yoshida, Minori (Winter 1949). "The Concepts behind the Ainu Bear Festival (Kumamatsuri)". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 5 (4): 345–350. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.5.4.3628594. JSTOR 3628594. S2CID 155380619.

- ^ Bonser, Wilfrid (1928). "The mythology of the Kalevala, with notes on bear-worship among the Finns". Folklore. 39 (4): 344–358. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1928.9716794. JSTOR 1255969.

- ^ Chaussonnet, Valerie (1995). Native Cultures of Alaska and Siberia. Washington, D.C.: Arctic Studies Center. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-56098-661-4.

- ^ Lee, Jung Young (1981). Korean Shamanistic Rituals. Mouton De Gruyter. pp. 14, 20. ISBN 978-90-279-3378-2.

- ^ Ward, P.; Kynaston, S. (1995). Wild Bears of the World. Facts on File, Inc. pp. 12–13, 17. ISBN 978-0-8160-3245-7.

- ^ Ward and Kynaston, pp. 12–13

- ^ Davisson, Zack (28 May 2013). "Onikuma – Demon Bear". Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai. Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Davidson, Peter (2005). The Idea of North. Reaktion Books. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-86189-230-0.

in the Meiji period .. handscroll of paintings of Ainu dwellings and customs .. The painter was Hirasawa Byozan and he titled the work Scenes of the Daily Life of the Ezo. His paintings are documentary, even anthropological in intent, for all their beauty.

- ^ "The Myth of Gojoseon's Founding-King Dan-gun". Archived from the original on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2017-08-29.

- ^ Tudor, Daniel (2013). Korea: The Impossible Country: The Impossible Country. Tuttle Publishing. pp. [1]. ISBN 978-1462910229.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features, and Historic Sites. McFarland. p. 57. ISBN 9780786422487.

- ^ Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion, 1985:263.

- ^

Vasmer, Max (1959–1961) [1950-1958]. Etimologicheskij slovar' russkogo yazyka Этимологический словарь русского языка [Etymological dictionary of the Russian language] (in Russian). Moscow: Прогресс. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

Праслав. *medvědь (первонач. 'поедатель меда', от мёд и *ěd-) представляет собой табуистическую замену исчезнувшего и.-е. *r̥kþos, др.-инд. r̥kṣas, греч. ἄρκτος, лат. ursus [...].

- ^ See for example the Russian folk-tales collected by Aleksandr Afansyev.

- ^ Second Book of Kings, 2:23–25

- ^ Pastoreau, Michel (2007). L'ours. Historie d'un roi déchu (in French). Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-021542-8.

- ^ Hall, Richard (1995). Viking Age Archaeology. Bloomsbury USA. pp. 43 and fig. 22. ISBN 978-0-7478-0063-7.

- ^ Patricia Turner, Charles Russell Coulter. Dictionary of ancient deities. 2001, page 248

- ^ "Jambavan: The only one who saw Lord Rama and Krishna".

- ^ Delarue, Paul (1949), "Le Conte populaire français: Inventaire analytique et méthodique", Nouvelle revue des traditions populaires, 1 (4), Presses Universitaires de France: 318–320, ISBN 9782706806346 JSTOR 40991689 (in French)

- ^ Żakowska, Magdalena (2013). "Bear in the European Salons: Russia in German Caricature, 1848–1914".

- ^ Raven-Hill, Leonard (13 December 1911). "As Between Friends". Punch. 141: 429. Archived from the original on 2017-02-20. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "What the West thinks about Russia is not necessarily true". Telegraph. 23 April 2009. Archived from the original on 2015-12-06. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ "Forest Fire Prevention – Smokey Bear (1944–Present)". Ad Council. 1944-08-09. Archived from the original on 2010-12-02. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ "Civic Heraldry of England and Wales-Warwickshire". Archived from the original on 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

- ^ "The first Buddy Bears in Berlin". Buddy Bär Berlin. 2008. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Väätäinen, Erika (2022-02-28). "Exploring Finnish Mythology Creatures And Finnish Folklore". Scandification. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ "The Kalevala: Rune XLVI. Otso the Honey-eater". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2023-01-26.

- ^ https://finland.fi/life-society/iconic-finnish-nature-symbols-stand-out/ ICONIC FINNISH NATURE SYMBOLS STAND OUT

- ^ Iltanen, Jussi: Suomen kuntavaakunat (2013), Karttakeskus, ISBN 951-593-915-1

- ^ https://memphismagazine.com/travel/savoring-heritage/ Savoring Heritage: A Memphis Writer explores her daughter's Finnish roots.

- ^ Domingo, M.R. (27 January 2015). "El «cambio de sexo» del Oso y el Madroño". ABC.

- ^ "Pooh celebrates his 80th birthday". BBC News. 24 December 2005. Archived from the original on 2006-04-25. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ "About". Paddington.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Walt Morey, 84; Author of 'Gentle Ben'". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 14 January 1992. Archived from the original on 2016-10-23. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ^ Kennedy, Patrick, ed. (1866). "The Brown Bear of Norway". Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts. Macmillan. pp. 57–67.

- ^ Elms, Alan C. (July–September 1977). ""The Three Bears": Four Interpretations". The Journal of American Folklore. 90 (357): 257–273. doi:10.2307/539519. JSTOR 539519.

- ^ Ashliman, D. L. (2004). Folk and Fairy Tales: A Handbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-0-313-32810-7.

- ^ Mallory, Michael (1998). Hanna-Barbera Cartoons. Hugh Lauter Levin. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-88363-108-9.

- ^ Browne, Ray B.; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. p. 944. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- ^ Holmes, Elizabeth (9 February 2007). "Care Bears Receive a (Gentle) Makeover". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2018-01-18. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- ^ Cannadine, David (1 February 2013). "A Point of View: The grownups with teddy bears". BBC. Archived from the original on 2017-04-25. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Wizards of the Coast, Inc, ed. (2021). Dungeon master's guide =: Guía del dungeon master. Renton, WA: Wizards of the Coast. ISBN 978-0-7869-6753-7. OCLC 1256628187.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Ptolemy's Almagest First printed edition, 1515". Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "The Great Bear Constellation Ursa Major". Archived from the original on 30 November 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "Ἀρκτοῦρος". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus. Archived from the original on 2017-03-07. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Schaefer, Bradley E. (November 2006). "The Origin of the Greek Constellations: Was the Great Bear constellation named before hunter nomads first reached the Americas more than 13,000 years ago?". Scientific American, reviewed at Brown, Miland (30 October 2006). "The Origin of the Greek Constellations". World History Blog. Archived from the original on 2017-04-01. Retrieved 9 April 2017; Berezkin, Yuri (2005). "The cosmic hunt: variants of a Siberian – North-American myth". Folklore. 31: 79–100. doi:10.7592/FEJF2005.31.berezkin.

- ^ A. Irving Hallowell (1925). "Bear Ceremonialism in the Northern Hemisphere". American Anthropologist. 28: 2. doi:10.1525/aa.1926.28.1.02a00020.

- ^ Nioradze, Georg. "Der Schamanismus bei den sibirischen Völkern", Strecker und Schröder, 1925.

- ^ a b Prudence Jones & Nigel Pennick (1997). "Late Germanic Religion". A History of Pagan Europe. Routledge; Revised edition. pp. 154–56. ISBN 978-0415158046.

- ^ Danielli, M, "Initiation Ceremonial from Norse Literature", Folk-Lore, v56, 1945 pp. 229–45.