Cuban Spanish

| Cuban Spanish | |

|---|---|

| español cubano (Spanish) | |

| Pronunciation | [espaˈɲol kuˈβano] |

| Ethnicity | Cubans |

Native speakers | 11 million (2011)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Academia Cubana de la Lengua |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | cuba1237 |

| IETF | es-CU |

Cuban Spanish is the variety of the Spanish language as it is spoken in Cuba. As a Caribbean variety of Spanish, Cuban Spanish shares a number of features with nearby varieties, including coda weakening and neutralization, non-inversion of Wh-questions, and a lower rate of dropping of subject pronouns compared to other Spanish varieties. As a variety spoken in Latin America, it has seseo and lacks the vosotros pronoun.

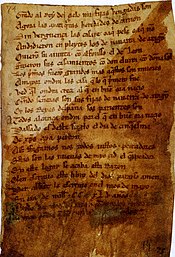

Origins

[edit]Cuban Spanish is most similar to, and originates largely from, the Spanish that is spoken in the Canary Islands and Andalusia. Cuba owes much of its speech patterns to the heavy Canarian migrations of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The accent of La Palma is the closest of the Canary Island accents to the Cuban accent. Many Cubans and returning Canarians settled in the Canary Islands after the revolution of 1959. Migration of other Spanish settlers (Asturians, Catalans, Castilians), and especially Galicians[2] also occurred, but left less influence on the accent.

Much of the typical Cuban vocabulary stems from Canarian lexicon. For example, guagua ('bus') differs from standard Spanish autobús. An example of Canarian usage for a Spanish word is the verb fajarse ('to fight').[3] In Spain, the verb would be pelearse, and fajar exists as a non-reflexive verb related to the hemming of a skirt.

Much of the vocabulary that is peculiar to Cuban Spanish comes from the different historic influences on the island. Many words come from the Canary Islands, but some words are of West African, French, or indigenous Taino origin, as well as peninsular Spanish influence from outside the Canary Islands, such as Andalusian or Galician.

The West African influence is due to the large Afro-Cuban population, most of whom are descended from African slaves imported in the 19th century. Some Cuban words of African origin include chévere 'wonderful', asere 'friend', and orishá 'Yoruba deity'. In addition, different Afro-Cuban religions and secret societies also different African languages in their practices and liturgies.[4]

Many Afro-Cubans in the 19th century also spoke Bozal Spanish, derived from the term bozales, which originally referred to muzzles for wild dogs and horses, and came to be used to refer to enslaved Africans who spoke little Spanish. Some elements of Bozal Spanish can still be found in the speech of elderly Afro-Cubans in remote rural areas, in Palo Mayombe chants, and in trance states during possession rituals in Santería.[4]

Due to historical commercial ties between the US and Cuba, American English has lent several words, including some for clothing, such as pulóver (which is used to mean "T-shirt") and chor ("shorts", with the typical Spanish change from English sh to ch, like mentioned above, ⟨ch⟩ may be pronounced [ʃ], the pronunciation of English "sh"). Anglicisms related to baseball, such as strike and foul, are frequently employed, with Spanish pronunciation.[4]

Phonology

[edit]Cuban Spanish is marked by a variety of phonological features that make it similar to, and distinct from, many other dialects of Spanish. Like other Latin American Spanish varieties, this dialect is seseante, meaning there is no distinction between ⟨s⟩, ⟨z⟩, and soft ⟨c⟩ sounds, differing from a Peninsular Spanish dialect. Cuban Spanish is also similar to most other Latin American dialects by using yeísmo; the letters ⟨y⟩ and ⟨ll⟩ are both pronounced [ʝ].[5]

Similar to speakers of other Caribbean dialects, Cuban Spanish speakers exhibit the weak pronunciation of consonants, especially at the end of a syllable. A syllable-final /s/ may either be aspirated and be pronounced as [h] or may even be deleted, in a process known as elision. Where some speakers would pronounce a word like estar ('to be') as [esˈtaɾ], pronouncing /s/ as alveolar, many Caribbean Spanish speakers aspirate the /s/ and produce [ehˈtaɾ],[6] or elide it altogether, pronouncing [eˈtaɾ].[5][6] This trait is shared with most American varieties of Spanish spoken in coastal and low areas (Lowland Spanish), as well as with Canarian Spanish and the Spanish spoken in the southern half of the Iberian Peninsula.

Take for example, the following sentence:

Esos perros no tienen dueños (Eso' perro' no tienen dueño')

[ˈesoh ˈperoh no ˈtjeneŋ ˈdweɲoh]

('Those dogs do not have owners')

Also, because this feature has variable realizations, any or all instances of [h] in the above example may be dropped, potentially rendering [ˈeso ˈpero no ˈtjeneŋ ˈdweɲo]. Other examples: disfrutar ("to enjoy") is pronounced [dihfɾuˈtaɾ], and fresco ("fresh") becomes [ˈfɾehko]. In Havana, después ("after[ward]") is typically pronounced [dehˈpwe] (de'pué'/despué').

Another instance of consonant weakening in Cuban Spanish (as in many other dialects) is the deletion of intervocalic /d/ in the participle ending -ado (-ao/-a'o), as in cansado (cansao/cansa'o) [kanˈsao] ("tired"). More typical of Cuba and the Caribbean is the elision of final /r/ in some verb infinitives, or merger with -/l/; e.g. parar, 'to stop', can be realized as [paˈɾal] or [paˈɾa] (paral/pará).

The voiceless velar fricative [x] (spelled ⟨g⟩ before ⟨e⟩ or ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩) is usually aspirated or pronounced [h], which is also common in Andalusian and Canarian dialects and some Latin American dialects.

Another common characteristic of Caribbean Spanish is the tendency for other processes to affect consonants in the final position such as /n/ velarization and neutralization of liquid consonants.[5] Word-final /n/ becomes [ŋ], such as in the word hablan (“they talk”), pronounced [a βlaŋ #].[5][7] Syllable-final /r/ may become [l] or [j], or even become entirely silent. Final /r/ more frequently becomes /l/ in the eastern and central regions of Cuba.[8] For example, in words such as carne (“meat”) or amor (“love”) many speakers of this dialect will produce the words as [kalne] or [amol].[9] Postvocalic [ð] tends to disappear entirely. All of these characteristics occur to one degree or another in other Caribbean varieties, as well as in many dialects in Andalusia (in southern Spain)—the place of historical origin of these characteristics.

In some areas of Cuba, the voiceless affricate [tʃ] (spelled ch) is deaffricated to [ʃ].

The Spanish of the eastern provinces (the five provinces comprising what was formerly Oriente Province) is closer to that of the Dominican Republic than to the Spanish spoken in Havana.[10]

There also exists a phonological feature unique to Cuba called the toque or golpe (“tap” or “hit”). This phonological process occurs within a consonant cluster that is composed of a liquid consonant, i.e., [ɾ] or [l], and an occlusive or nasal consonant, i.e., [p][t][g][b][t][k][n][m]. Instead of producing the liquid, a Cuban speaker may produce the glottal stop consonant [ʔ].[5] For example, a word like algodón ('cotton') will have the [l] phoneme substituted for the [ʔ] sound, producing [aʔ-go-ˈðon].

In western Cuba /l/ and /ɾ/ in a syllable coda can be merged with each other and assimilated to the following consonant, resulting in geminates. At the same time, the non-assimilated and unmerged pronunciations are more common. Example pronunciations, according to the analysis of Arias (2019) which transcribes the merged, underlying phoneme as /d/:[11]

| /l/ or /r/ + /f/ | > | /d/ + /f/: | [ff] | a[ff]iler, hue[ff]ano | (Sp. 'alfiler', 'huérfano') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /s/ | > | /d/ + /s/: | [ds] | fa[ds]a, du[ds]e | (Sp. 'falsa or farsa', 'dulce') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /h/ | > | /d/ + /h/: | [ɦh] | ana[ɦh]ésico, vi[ɦh]en | (Sp. 'analgésico', 'virgen') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /b/ | > | /d/ + /b/: | [b˺b] | si[b˺b]a, cu[b˺b]a | (Sp. 'silba or sirva', 'curva') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /d/ | > | /d/ + /d/: | [d˺d] | ce[d˺d]a, acue[d˺d]o | (Sp. 'celda or cerda', 'acuerdo') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /g/ | > | /d/ + /g/: | [g˺g] | pu[g˺g]a, la[g˺g]a | (Sp. 'pulga or purga', 'larga') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /p/ | > | /d/ + /p/: | [b˺p] | cu[b˺p]a, cue[b˺p]o | (Sp. 'culpa', 'cuerpo') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /t/ | > | /d/ + /t/: | [d˺t] | sue[d˺t]e, co[d˺t]a | (Sp. 'suelte o suerte', 'corta') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /ʧ/ | > | /d/ + /ʧ/: | [d˺ʧ] | co[d˺ʧ]a, ma[d˺ʧ]arse | (Sp. 'colcha o corcha', 'marcharse') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /k/ | > | /d/ + /k/: | [g˺k] | vo[g˺k]ar, ba[g˺k]o | (Sp. 'volcar', 'barco') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /m/ | > | /d/ + /m/: | [mm] | ca[mm]a, a[mm]a | (Sp. 'calma', 'alma o arma') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /n/ | > | /d/ + /n/: | [nn] | pie[nn]a, ba[nn]eario | (Sp. 'pierna', 'balneario') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /l/ | > | /d/ + /l/: | [ll] | bu[ll]a, cha[ll]a | (Sp. 'burla', 'charla') |

| /l/ or /r/ + /r/ | > | /d/ + /r/: | [r] | a[r]ededor | (Sp. 'alrededor') |

Morphology and syntax

[edit]

Cuban Spanish typically uses the diminutive endings -ico and -ica (instead of the standard -ito and -ita) with stems that end in /t/. For example, plato ("plate") > platico (instead of platito), and momentico instead of momentito; but cara ("face") becomes carita.[12] This form is common to the Venezuelan, Cuban, Costa Rican, Dominican, and Colombian dialects.

The suffix -ero is often used with a place name to refer to a person from that place; thus habanero, guantanamera, etc.[12] A person from Santiago de Cuba is santiaguero (compare santiagués "from Santiago de Compostela (Galicia, Spain)", santiaguino "from Santiago de Chile").

Wh-questions, when the subject is a pronoun, are usually not inverted. Where speakers of most other varieties of Spanish would ask "¿Qué quieres?" or "¿Qué quieres tú?", Cuban speakers would more often ask "¿Qué tú quieres?"[12] (This form is also characteristic of Dominican, Isleño, and Puerto Rican Spanish.[12][13])

Cuban Spanish also frequently uses expressions with personal infinitives, a combined preposition, noun or pronoun, and verbal infinitive where speakers in other dialects would typically use a conjugated subjunctive form. For example, eso sucedió antes de yo llegar aquí, instead of …antes de que yo llegara… 'that happened before I arrived here'. This type of construction is found elsewhere in the Caribbean and occurs in all speech styles.[8]

Cuban Spanish uses the familiar second-person pronoun tú in many contexts where other varieties of Spanish would use the formal usted. While Cuban Spanish has always preferred tú to usted, the use of usted has become increasingly rare after the Revolution.[8] Voseo is practically non-existent in Cuba.[12] It was historically present in the countryside of eastern Cuba. Pedro Henríquez Ureña alleged that it often used the object and possessive pronouns os and vuestro instead of te and tuyo. Its present-tense conjugations ending in -áis, -éis, and -ís, and future-tense conjugations in -éis.[14][15]

In keeping with the socialist polity of the country, the term compañero/compañera ("comrade" or "friend") is often used instead of the traditional señor/señora.[16][17] However, Corbett (2007:137) states that the term compañero has failed to enter the popular language, and is rejected by many Cubans opposed to the current regime, citing a misunderstanding with a Cuban who refused to be addressed as compañera.

Influence of the Canary Islands

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

Many words in traditional Cuban Spanish can be traced to those of the Spanish spoken in the Canary Islands.[18] Many Canary Islanders emigrated to Cuba and had one of the largest parts in the formation of the Cuban dialect and accent. There are also many elements from other areas of Spain such as Andalusian, Galician, Asturian, Catalan, as well as some African influence. Cuban Spanish is very close to Canarian Spanish. Canarian emigration has been going on for centuries to Cuba, and were also very numerous in emigration of the 19th, and 20th centuries.

Through cross emigration of Canarians and Cubans, many of the customs of Canarians have become Cuban traditions and vice versa.

The music of Cuba has become part of the Canarian culture as well, such as mambo, salsa, son, and punto Cubano. Because of Cuban emigration to the Canary Islands, the dish "moros y cristianos" (black beans and rice mixed together with traditional spices, different from "frijoles negros", which is a thick black bean soup served over white rice), also known as simply "moros", can be found as one of the foods of the Canary Islands; especially the island of La Palma. Canary Islanders were the driving force in the cigar industry in Cuba, and were called "Vegueros". Many of the big cigar factories in Cuba were owned by Canary Islanders. After the Castro revolution, many Cubans and returning Canarians settled in the Canary islands, among whom were many cigar factory owners such as the Garcia family. The cigar business made its way to the Canary Islands from Cuba, and now the Canary Islands are one of the places that are known for cigars alongside Cuba, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Honduras. The island of La Palma has the greatest Cuban influence out of all seven islands. Also, La Palma has the closest Canarian accent to the Cuban accent, due to the most Cuban emigration to that island.

Many of the typical Cuban replacements for standard Spanish vocabulary stem from Canarian lexicon. For example, guagua (bus) differs from standard Spanish autobús the former originated in the Canaries and is an onomatopoeia stemming from the sound of a Klaxon horn (wah-wah!). The term of endearment "socio" is from the Canary Islands. An example of Canarian usage for a Spanish word is the verb fajarse[19] ("to fight"). In standard Spanish the verb would be pelearse, while fajar exists as a non-reflexive verb related to the hemming of a skirt. Cuban Spanish shows strong heritage to the Spanish of the Canary Islands.

Many names for food items come from the Canary Islands as well. The Cuban sauce mojo, is based on the mojos of the Canary Islands where the mojo was invented. Also, Canarian ropa vieja is the father to Cuban ropa vieja through Canarian emigration. Gofio is a Canarian food also known by Cubans, along with many other kinds.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Spanish (Cuba) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Lipski (2011:540)

- ^ fajar at Diccionario de la Real Academia Española.

- ^ a b c Lipski (2011:541–542)

- ^ a b c d e Schwegler, Armin (2010). Fonética y fonolgía españolas [Spanish phonetics and phonology] (in Spanish). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 408–410.

- ^ a b Terrell, Tracy. "Final /s/ in Cuban Spanish". Hispania. 62 (4): 599–612. doi:10.2307/340142. JSTOR 340142.

- ^ Canfield (1981:42)

- ^ a b c Lipski (2011:542)

- ^ Alfaraz, Gabriela. "The lateral variant of (r) in Cuban Spanish". Selected Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics.

- ^ Lipski (1994:227)

- ^ Arias (2019).

- ^ a b c d e Lipski (1994:233)

- ^ Lipski (1994:335)

- ^ Henríquez Ureña (1940:49)

- ^ Real Academia Española. "voseo | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas". «Diccionario panhispánico de dudas» (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Brumfield, Brittany; Carpenter, Lisa; Sloan, Loren. "Social Life in Cuba". Archived from the original on 12 February 2019.

In a social setting, the use of compañero/compañera has almost entirely replaced the more formal senor/senora. This does not apply when speaking to elderly or strangers, where Cubans use formal speech as a sign of respect.

- ^ Sánchez-Boudy, José (1978). Diccionario de cubanismos más usuales (Cómo habla el cubano) (in Spanish). Miami: Ediciones Universal.

En Cuba, hoy en día, se llama a todo el mundo «compañero».

- ^ BBC Spanish Mundo: La poderosa influencia de las Canarias en el español caribeño (y qué hace que los canarios suenen como cubanos o venezolanos) (in Spanish)

- ^ fajar Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine at Diccionario de la Real Academia Española.

Bibliography

[edit]- Arias, Álvaro (2019). "Fonética y fonología de las consonantes geminadas en el español de Cuba". Moenia. 25: 465–497.

- Canfield, D. Lincoln (1981), Spanish Pronunciation in the Americas, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-09263-1

- Corbett, Ben (2007). This Is Cuba: an Outlaw Culture Survives. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465009961. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Guitart, Jorge M. (1997), "Variability, Multilectalism, and the Organization of Phonology in Caribbean Spanish Dialects", in Martínez-Gil, Fernando; Morales-Front, Alfonso (eds.), Issues in the Phonology and Morphology of the Major Iberian Languages, Georgetown University Press, pp. 515–536

- Henríquez Ureña, Pedro (1940). El Español en Santo Domingo (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Instituto de Filología de la Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Lipski, John M. (1994), Latin American Spanish, Longman, ISBN 978-0-582-08761-3

- Lipski, John M. (2011). "Language: Spanish" (PDF). In West-Durán, Alan (ed.). Cuba: People, Culture, History. Cengage Gale. pp. 539–543. ISBN 9780684316819. Retrieved 8 February 2022.