Coldingham Priory

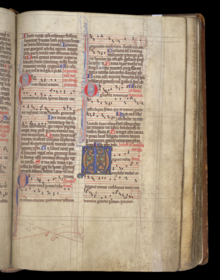

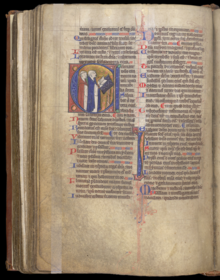

Remains of the priory | |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | x 1139 |

| Disestablished | 1606 |

| Mother house | Durham Cathedral Priory Dunfermline Abbey from 1378 |

| Diocese | Diocese of St Andrews |

| Controlled churches | Aldcambus; Ayton; Berwick Holy Trinity; Berwick St Laurence; Berwick St Mary's; Bondington; Coldingham; Earlston; Ednam; Edrom; Fishwick; Foulden; Gordon; Lamberton; Mordington; Nenthorn; Smailholm; Stichill; Swinton |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | David I of Scotland |

| Site | |

| Coordinates | 55°53′11.4″N 2°9′18.8″W / 55.886500°N 2.155222°W |

Coldingham Priory was a house of Benedictine monks. It lies on the south-east coast of Scotland, in the village of Coldingham, Berwickshire. Coldingham Priory was founded in the reign of David I of Scotland, although his older brother and predecessor King Edgar of Scotland had granted the land of Coldingham to the Church of Durham in 1098, and a church was constructed by him and presented in 1100. The first prior of Coldingham is on record by the year 1147, although it is likely that the foundation was much earlier. The earlier monastery at Coldingham was founded by St Æbbe sometime c. AD 640. Although the monastery was largely destroyed by Oliver Cromwell in 1650,[1] some remains of the priory exist, the choir of which forms the present parish church of Coldingham and is serviced by the Church of Scotland.

Early Middle Ages

[edit]St Æbbe the Elder

[edit]Early life

[edit]Æbbe was born c. AD 615 into both royal houses of Northumbria, the daughter of King Æthelfrith of Bernicia, (the first king of Northumbria from c. 604) and Acha, a daughter of Ælla of Deira. In 616, she and her family were forced to flee with her family to Dál Riata following the death of her father at the Battle of the River Idle which was fought against Rædwald of East Anglia. The defeat led to the succession of Æbbe's uncle, Edwin of Northumbria.

At the court of Eochaid Buide she and her brothers converted to Christianity. King Eochaid's father, Áedán mac Gabráin had been a contemporary of St Columba, and his grandfather, Conall mac Comgaill, had given the saint leave to build his mission on Iona. (Eochaid's father, Áedán had been comprehensively defeated by the forces of Æthelfrith at the Battle of Degsastan in AD 603.)

Following the defeat of Edwin at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633 against Penda of Mercia and Cadwallon ap Cadfan, and the subsequent despoliation of Northumbria, Æbbe's brother Oswald gained control of the kingdom by AD 635, enabling the return of his family.

Abbess Æbbe

[edit]

In c. 635 King Oswald introduced Columban monks to the island of Lindisfarne, opposite his fortress of Bebbanburg, in order to Christianise his mainly pagan peoples. Under these auspices, Æbbe first founded a monastery at Ebchester, then at what Bede refers to as Urbs Coludi (Sax. Coldingaham). It is uncertain when these establishments were founded, although Æbbe first appears in records of the Lindisfarne by AD 642, the date of her brother's death. Oswald was succeeded by a younger brother, Oswiu. Both brothers were given the title of Bretwalda by Bede. The abbey was sited on what is now called Kirk-Hill, but is commonly called the Brugh (a corruption of Sax. burh- fort), on the headland at present-day St Abbs, separated from the world by a deep trench and a high palisade. This religious house lasted for about 40 years and was a double monastery of both monks and nuns governed by Æbbe.

Around 660 St Æthelthryth, Queen of Æbbe's nephew, Ecgfrith of Northumbria took the veil as a nun,[1] under the tutelage of St Wilfrid. Æthelthryth was later to found Ely Cathedral. Saint Cuthbert arrived at Coldingham in 661 to instruct the community.

Æbbe presumably had difficulties maintaining discipline. One of the monks, Adomnán by name (not the same man as St Adomnán the abbot of Iona), prophesied the house's destruction. The abbey at Coldingham burnt down in 679[1] soon after Æbbe's death and was rebuilt.[1] Æbbe is remembered as a religieuse of great piety who helped to spread Christianity in Northumbria and beyond. Her feast day is on 25 August.

All that remains today at the Kirk-hill is the trench, a few grassy mounds and the ruin of a 14th-century church erected by monks of the later priory. There are few references to the house at Coldingham from its destruction until its revival in the 11th century, excepting tales of a later superior also called Æbbe. It is likely that the house was reformed as a community of nuns at some point in the 8th or 9th centuries, as by the formation of the Benedictine priory in AD 1100 there was a thriving cult of St Æbbe at the site. The house appears to have moved from its original site at St Abb's Head to its present location around this time.

St Æbbe the Younger

[edit]St Æbbe the Younger is a semi-mythological abbess of Coldingham. In AD 870 a raiding party of Danes landed at the coast near the house and sacked it. Legend has it that faced with the dishonour that St Æbbe and her sisters expected, they mutilated themselves by cutting off their noses and lips. The nuns made themselves as unappealing as possible to the marauders, thereby foregoing rape and accepting martyrs' deaths. The story is somewhat unreliable as there are no near-contemporary accounts, and it is first recorded by Matthew Paris some 250 years later.

Founding of the Priory Church

[edit]In 1097, Étgar mac Maíl Choluim had gained control of Scotland from his uncle Domnall Bán. The son of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, he attacked and deposed King Domnall with the backing of William Rufus of England. According to a charter of 1095, he was given the "land of Lothian" by the English king before securing possession of Scotland-proper. Following his takeover of Lothian and Scotland, in 1098 he confirmed possession of the lands of Coldingham by the monks of Durham, and attended the consecration of the new church to St Mary in 1100. In the following years, the brethren of Coldingham were to gain many charters of land, so that within fifty years they were able to assume the dignity of a Priory.

The Priory

[edit]The years up to 1376 appear to have been normal: the sacristan submitted his usual account roll for the accounting year 1375-6 but there is, thereafter, no Coldingham account roll surviving in the Durham muniments until 1399.[2] The crisis of 1378-9 is explained in the Scotichronicon, which has the text of a charter of Robert II, dated at Perth on 25 July 1378 granting Coldingham Priory to another Benedictine house, Dunfermline Abbey, on the stated grounds that English monks were a threat to the king and country and had damaged the neighbourhood.[3] The Scotichronicon adds that Prior William Claxton had been convicted as a spy, revealing Scottish secrets and illegally transporting money out of the kingdom.[4] The king's charter apparently followed an attempt by Durham Priory to block the formal appointment of A[dam] of C[rail], [Monk of Dunfermline], to whom Robert II had given possession of its Coldingham cell.[5]

Coldingham Priory had been established by, and had for centuries belonged to, Durham Priory but, at this critical point, English monks were unable to defend a long-established position by an appeal to the pope, since just before Robert II issued his charter, Scotland became subject to a different pope (Clement VII) who was not recognised in England (which followed Urban VI).[6] In 1379 Clement VII commissioned two Scottish bishops to summon Prior Claxton to answer criminal charges (allegedly of sacrilege, robbery, homicide, rapine and devastation, as well as felonies against King Robert).[7] The charges, which also included one of reducing the size of the Coldingham convent to a prior and two or three resident monks, resulted, after a hearing at Holyrood on 28 April 1379 before the bishop of St Andrews in full consistory, in Claxton being deprived and replaced as Prior of Coldingham by Michael of Inverkeithing, monk of Dunfermline.[8] Dunfermline Abbey certainly gained actual control and the Abbot of Dunfermline and Prior Michael were able to give Coldingham lands to George Dunbar, Earl of March in 1380 and, probably in 1382, to Sir John Swinton.[9] Prior Claxton, nominally still the lawful Prior in English eyes, lived (certainly from 1381 to 1382) as a lodger in the Durham cell nearest Scotland, Holy Island Priory, paying 2s. 6d. a week for his board.[10]

In the wake of this crisis, the Priory was made the head (caput) for the Barony of Coldingham, the Prior being the feudal lord. On 2 January 1392 Sir Robert de Lawedre of The Bass was a witness to a royal charter to the Priory of Coldingham confirming them in all of their ancient possessions, and signed at Linlithgow.[11]

In conflict

[edit]In November 1528 the Earl of Angus stayed at the Priory and wrote letters to the Earl of Northumberland and Henry VIII about his success against the forces of James V who were besieging Tantallon Castle.[12]

In April 1544, during the war known as the Rough Wooing, a garrison put in by George Douglas (an ally of the English) was driven out by John Hume.[13] In June 1544, an English force led by Sir George Bowes, John Widdrington, Henry Eure (a son of William Eure), and Lionel Grey burnt the claustral buildings.[14]

Regent Arran briefly established a garrison of six gunners in the Priory in October 1544.[15] Henry VIII gave orders for Coldingham to be taken and fortified. In November, George Bowes retook the Priory. William Eure then sent George Bowes and the Italian military engineer Archangelo Arcano to set up a fort at Coldingham. George Bowes was made the "petty-captain" with 100 men, and some gunners from the Berwick garrison, and ten Irish arquebusiers.[16]

Priors

[edit]Please see main article:Prior of Coldingham

Reformation and the end of Monasticism

[edit]

After the Reformation the Priory and Barony passed into secular hands. In 1592 the Priory became the possession of Alexander Home, 1st Earl of Home and in November he and his wife Christian Douglas moved in, organising repairs and moving furniture in the hall and chamber.[17] The barony of Coldingham, previously the possession of the Priory, was erected as a temporal lordship, under the Great Seal, dated 16 October 1621, upon John Stewart, second son of Francis Stewart, 1st Earl of Bothwell, who was the last Commendator of Coldingham Priory. He personally received from the Crown a charter dated 19 October 1621, of the lands and baronies belonging to the Priory, united into one barony. Feu charters in the hands of many of the small proprietors in the neighbourhood were originally granted by him, either as Commendator or Lord. John Stewart disponed these lands and the barony on 16 June 1622 to Francis Stewart, eldest son of the Earl.

Negotiations subsequently took place between the Earl of Home and the Stewarts for the Earl's acquisition of the Barony and its possessions. These apparently failed through the Earl's inability to provide the purchase price.[18]

It is an interesting reflection on feudal superiors to note that in a petition to King Charles I dated 4 April 1636 the feuars and tenants still refer to themselves as "the vassals of the Abbacy of Coldingham". In this petition the vassals plead the oppression of the Stewarts and ask for the King to become the only superior lord of Coldingham.[19]

In Cromwell's time, the Homes of Renton seem to have taken the barony of Coldingham from the Stewarts in lieu of debt, as Harry Home, natural son of John Home of Renton apprised the barony and its lands on 26 November 1656 from Robert Stewart, lawful son of the now-deceased Francis Stewart. Harry Home subsequently assigned his right to Alexander Home, eldest lawful son of said John Home of Renton, the Precept by Oliver Cromwell being dated at Edinburgh, 10 August 1658.[20]

In 1857 there were about 70 'heritors' or feu-holders in the barony.[21] Today there are many more, all converted into freeholders with the abolition of feudal land tenure by the Scottish Parliament in November 2005.

Today

[edit]

Today Coldingham Priory is still home to the local Church of Scotland parish church for Coldingham, which meets within the restored choir of the Priory and as such the church building includes remnants of a 13th-century building. Coldingham Priory is the only major medieval church in South-East Scotland to have its remains continue in use as an active present-day church.

Outside of the church building the ruins were in a very poor state, badly eroded, overgrown and at risk of collapse. But with the help of the Heritage Lottery Fund the site has been rejuvenated: the ruins conserved, footpaths reinstated and a wasteland transformed into a community garden with a monastic theme, concentrating on plants with culinary, medicinal and aromatic properties. There are also interpretation boards, explaining the hundreds of years of history contained within its walls, while a year-long education programme engaged schools and community groups in many diverse activities relating to the Priory and its conservation.

A partnership consisting of Historic Scotland, Scottish Borders Council, Scottish Natural Heritage, Archaeology Scotland, the Friends of Coldingham Priory, and the Tweed Forum was awarded a grant of £237,500 from HLF to conserve the ruins of Coldingham Priory and encourage community use of this site.[22]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Richard Barrie Dobson (1967), "The Last English Monks on Scottish Soil: The Severance of Coldingham Priory from the Monastery of Durham 1461-78", The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 46, No. 141, Part 1 (Apr., 1967), pp. 1–25 JSTOR 25528677

- Alfred Lawson Brown (1972), "The Priory of Coldingham in the late fourteenth century", Innes Review, vol. 23(2) pp. 91–101 doi:10.3366/inr.1972.23.2.91

- Norman Macdougall (1972), "The Struggle for the priory of Coldingham, 1472-1488", Innes Review, vol. 23(2), pp. 102–114 doi:10.3366/inr.1972.23.2.102

- Rev. Mark Dilworth (1972), "Coldingham Priory and the Reformation: Notes on Monks and Priors"", Innes Review, vol. 23(2), pp. 115-37 doi:10.3366/inr.1972.23.2.115

Older works

[edit]- The following may no longer reflect current scholarship

- George Chalmers (1810), Caledonia, vol 2; republished edn (Paisley, 1888), vol 3, 323-5.

- Alexander William Carr (1836), A history of Coldingham priory. (IA second copy)

- William King Hunter (1858), History of the Priory of Coldingham (Edinburgh, 1858);

- Rev J.L. Low (1885), "Coldingham", Archaeologica Aeliana vol 11, Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, p. 186.

- Andrew Thomson (1908), Coldingham: Parish and Priory (Galashiels, 1908)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d ""History of Coldingham", Coldingham Village History". Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ A.L. Brown, 'The Priory of Coldingham in the late fourteenth century', Innes Review, vol. 23 (1972) pp. 91-101 doi:10.3366/inr.1972.23.2.91, at p. 92.

- ^ Johannis de Fordun Scotichronicon, ed. W. Goodall (Edinburgh, 1759), vol. ii, 161-3); Brown, 'Priory of Coldingham', p. 91.

- ^ Brown, 'Priory of Coldingham', p. 91.

- ^ Undated letter, Prior Robert [Walworth] of Durham to Bishop William [Landel] of St Andrews, in The Correspondence, Inventories, Account Rolls, and Law Proceedings of the Priory of Coldingham, ed., James Raine, Surtees Society, vol. xii, (1841), available as https://books.google.pl/books/about/The_Correspondence_Inventories_Account_R.html?id=LCtSAAAAcAAJ&redir_esc=y (editor named, incorrectly, as Joseph Stevenson), no. xlviii, pp. 44-5; according to Brown, 'Priory of Coldingham', p. 92, Walworth’s letter dates 1374x8, probably 1375x8 and before Robert II’s charter.

- ^ Brown, 'Priory of Coldingham', p. 92.

- ^ Calendar of Papal Registers Relating to Great Britain and Ireland: Volume 4, 1362-1404, ed. W. H. Bliss and J. A. Twemlow (London, 1902), p. 236.

- ^ Brown, 'Priory of Coldingham', pp. 92-3.

- ^ Brown, 'Priory of Coldingham', p. 93.

- ^ Rollason, D. and L., eds., Durham Liber vitae : London, British Library, MS Cotton Domitian A.VII : edition and digital facsimile with introduction, codicological, prosopographical and linguistic commentary, and indexes including the Biographical Register of Durham Cathedral Priory (1083–1539) by A. J. Piper, (London: British Library, 2007), vol. iii, 274; Brown, 'Priory of Coldingham', p. 93.

- ^ The Great Seal of Scotland, confirmed 16 March 1391/2, number 839

- ^ State Papers Henry Eighth, vol. 4 part 4 (London, 1836), pp. 521-3.

- ^ Joseph Bain, Hamilton Papers, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1890), p. 722.

- ^ A. F. Pollard, Tudor Tracts (London: Archibald Constable, 1903), p. 50.

- ^ James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1908), pp. 325, 329.

- ^ Joseph Bain, Hamilton Papers, 2 (Edinburgh, 1892), pp. xxvii, 513 no. 367: Edmund Lodge, Illustrations of British History, vol. 1 (London, 1828), pp. 78–79, 81–82

- ^ Michael Pearce, 'A French Furniture Maker and the 'Courtly Style' in Sixteenth-Century Scotland', Regional Furniture vol. XXXII (2018), p. 132.

- ^ Historic Manuscripts Commission, Manuscripts of Colonel David Milne-Home of Wedderburn Castle, N.B., London, 1902: 13, 197-199

- ^ Historic Manuscripts Commission, Manuscripts of Colonel David Milne-Home of Wedderburn Castle, N.B., London, 1902: 201 - 202

- ^ Historic Manuscripts Commission, Manuscripts of Colonel David Milne-Home of Wedderburn Castle, N.B., London, 1902: 13, and 202-4

- ^ King Hunter, William (1858). History of the Priory of Coldingham. Edinburgh: Sutherland and Knox. pp. 105–6. ISBN 978-1-01-954568-3.

- ^ http://www.britarch.ac.uk/news/090116-coldingham The Council for British Archaeology, Coldingham Priory Project Goes Live

External links

[edit]- Historic Environment Scotland. "Coldingham Priory, claustral remains (SM383)".

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Coldingham Priory Church including former hearse house and store, graveyard, boundary walls, gatepiers and gates and excluding scheduled monument SM383, Coldingham (Category A Listed Building) (LB4059)".

- 640s establishments

- Christian monasteries established in the 7th century

- Double monasteries

- 680s disestablishments

- 1139 establishments in Scotland

- Benedictine monasteries in Scotland

- Berwickshire

- History of the Scottish Borders

- Category A listed buildings in the Scottish Borders

- Listed monasteries in Scotland

- Christian monasteries established in the 1130s

- Archaeological sites in the Scottish Borders

- 1606 disestablishments

- 1600s disestablishments in Scotland

- Burial sites of the Royal House of Northumbria

- Scheduled monuments in the Scottish Borders

- Former Christian monasteries in Scotland

- 7th-century church buildings in England