Chicago Picasso

| Chicago Picasso | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Pablo Picasso |

| Year | 1967 |

| Medium | Sculpture, COR-TEN steel Fabricator: American Bridge Company |

| Dimensions | 15 m (50 ft) |

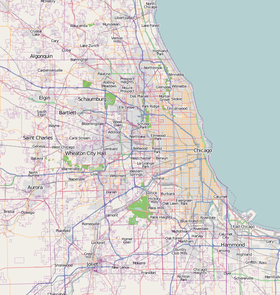

| Location | Daley Plaza, Chicago |

| 41°53′01″N 87°37′48″W / 41.88361°N 87.62997°W | |

The Chicago Picasso (often just The Picasso) is an untitled monumental sculpture by Pablo Picasso in Daley Plaza in Chicago, Illinois. The 1967 installation of The Picasso, "precipitated an aesthetic shift in civic and urban planning, broadening the idea of public art beyond the commemorative."[1]

The COR-TEN steel structure, dedicated on August 15, 1967, in the civic plaza in the Chicago Loop, is 50 feet (15.2 m) tall and weighs 162 short tons (147 t).[2] The Cubist sculpture by Picasso, who later said that it represented the head of his Afghan Hound Kabul,[3] was the first monumental abstract public artwork in Downtown Chicago, and has become a well-known landmark. Publicly accessible, it is known for its inviting jungle gym-like characteristics.[4] Visitors to Daley Plaza can often be seen climbing on and sliding down the base of the sculpture.

The sculpture was commissioned in 1963 by the architects of the Chicago Civic Center (now known as the Richard J. Daley Center), a modernist government office building and courthouse (also clad in COR-TEN), with an open granite-paved plaza. The commission was facilitated by the architect William Hartmann of the architectural firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.[5] Picasso completed a maquette of the sculpture in 1965, and approved a final model of the sculpture in 1966. The cost of constructing the sculpture was $351,959.17 (equivalent to $3.2 million in 2022[6]), paid mostly by three charitable foundations: the Woods Charitable Fund, the Chauncey and Marion Deering McCormick Foundation, and the Field Foundation of Illinois. Picasso himself was offered payment of $100,000 but refused, stating that he wanted to make his work a gift to the city.[7]

History

[edit]

An architect who worked on the Daley Center project, Richard Bennett, wrote Picasso a poem asking him to make the sculpture.[8] Picasso accepted saying "You know I never accept commissions to do any sort of work, but in this case I am involved in projects for the two great gangster cities" (the other being Marseille, France).

The sculpture was fabricated by the American Bridge Company division of the United States Steel Corporation in Gary, Indiana using COR-TEN steel, before being disassembled and relocated to Chicago.[2] The steel for this statue was rolled in the USS Gary Works 160/210" plate mill, then the largest rolling mill of its kind in the world. Before fabrication of the final steel sculpture was started, a 3.5 meter (~12 feet) tall wooden model was constructed for Picasso to approve; this was eventually sent to the Gary Career Center.[9] Ground was broken in Daley Plaza for the construction of the sculpture on May 25, 1967.[10]

The efforts of the City of Chicago to publicize the sculpture — staging a number of press events before the sculpture was completed, and displaying the maquette without a copyright notice — were cited as evidence in a 1970 U.S. District Court case where the judge ruled that the city's actions had resulted in the sculpture being dedicated to the public domain.[7]

Controversy

[edit]The sculpture was initially met with controversy.[11] Before the Picasso sculpture, public sculptural artwork in Chicago was mainly of historical figures.[5] One derisive Chicago City Council alderman, John Hoellen, immediately proposed replacing it with a statue of Chicago Cubs baseball great Ernie Banks,[12] and publicist Algis Budrys erected a giant pickle on the proposed site for his client, Pickle Packers International.[13] There was speculation on the subject, which has ranged from a bird, or aardvark to Picasso's pet Afghan Hound, a baboon head,[14] the Egyptian deity Anubis,[15] or Sylvette David, one of his models.

Newspaper columnist Mike Royko, covering the unveiling of the sculpture, wrote: "Interesting design, I'm sure. But the fact is, it has a long stupid face and looks like some giant insect that is about to eat a smaller, weaker insect." Royko did credit Picasso with understanding the soul of Chicago. "Its eyes are like the eyes of every slum owner who made a buck off the small and weak. And of every building inspector who took a wad from a slum owner to make it all possible. ... You'd think he'd been riding the L all his life."[16]

Inspiration

[edit]

At a reception for the unveiling of a large piece of public sculpture commissioned by a New York University, Picasso told Stanley Coren that the head of the sculpture is an abstract representation of his Afghan Hound named Kabul.[17]

Right now I have an Afghan Hound named Kabul. He is elegant, with graceful proportions, and I love the way he moves. I put a representation of his head on a statue that I created for Daley Plaza in Chicago and I do think of him sometimes while I am in my studio.[3]

Some have speculated it may have been inspired by a French woman, Sylvette David, now known as Lydia Corbett, who posed for Picasso in 1954. Then 19 years old and living in Vallauris, France, Corbett would accompany her artist boyfriend as he delivered chairs made of metal, wood and rope. One of those deliveries was to Picasso, who was struck by her high ponytail and long neck. "He made many portraits of her. At the time, most people thought he was drawing the actress Brigitte Bardot. But in fact, he was inspired by [Corbett]", Picasso's grandson Olivier Widmaier Picasso told the Chicago Sun-Times in 2004.[citation needed]

"I think the Chicago Sculpture was inspired by her", said the grandson, author of Picasso, the Real Family Story. Picasso made 40 works inspired by her, said the grandson, including The Girl Who Said No, reflecting their platonic relationship. The quality of the Picasso sculpture inspired other artists such as Alexander Calder, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Claes Oldenburg and Henry Moore.[citation needed]

In the 1970s Jacqueline Picasso explained to Neil Thomas, an Australian lady, it was simply a male baboon viewed from head-on. "Picasso loved the way the creature changed as you viewed it from different angles"; it was part of a continuation of his lifelong inspiration from Africa.[citation needed]

There was an ongoing dialogue between Picasso's sculpture and his painting.[18] A further possible influence could lie in his portraits of Jacqueline herself, made in the early 1960s, specifically Bust of a Woman (Jacqueline) from May 1962 (Zervos XX, 243, Private Collection).[19] The historian Patricia Stratton has made a convincing case for Jacqueline Roque Picasso as the model for the Chicago sculpture.[20]

Local and pop culture

[edit]

The Picasso was the site of an August 23, 1968, press conference in which Yippies Jerry Rubin, Phil Ochs, and others were arrested after nominating a pig — Pigasus — for president of the United States. This event was held days before the opening of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, which became known for its anti-Vietnam war protests.[21]

The sculpture was mentioned (and appears) in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers during the chase scene leading to the Richard J. Daley Center. It can also be seen briefly in the 1993 film The Fugitive, as Harrison Ford, playing Richard Kimble, and his pursuers run across the plaza, and in the 1986 film Ferris Bueller's Day Off as people in and under a reviewing stand dance to a song sung by Matthew Broderick, who plays Bueller. The sculpture also makes an appearance in the 1988 film Switching Channels starring Kathleen Turner, Burt Reynolds and Christopher Reeve.

The Chicago Picasso became and continues to be a well-known meeting spot for Chicagoans. Depending on the season and time of the month, there are musical performances, farmers' markets, a Christkindlmarkt, and other Chicago affairs which are held around the Picasso in Daley Plaza.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Lopez, Ruth (August 7, 2017). "The story behind the 'controversial' Picasso sculpture that became a symbol of Chicago". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ a b 1967 August 15—Picasso Statue Unveiled In Civic Center Plaza. Chicago Public Library (URL accessed August 14, 2005).

- ^ a b Coren, Stanley (June 15, 2011). "Picasso's Dogs". Modern Dog. Vancouver. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- ^ Artner, Alan G. (July 18, 2004). "Unfinished, but engaging, public art – 'Cloud Gate' and Crown Fountain intrigue". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ a b "Picasso: Pablo and the Boss: The Amazing Story of Chicago's Picasso – WTTW". www.wttw.com.

- ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- ^ a b The Letter Edged in Black Press, Inc. v. Public Building Commission of Chicago 320 F. Supp. 1303 (1970)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Davich, Jerry (January 5, 2006). "Unveiling Picasso's steel city beginnings". The Times of Northwest Indiana. Lee Enterprises. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ Barry, Edward (May 26, 1967). "Break Ground for Big Statue in Civic Center". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Company.

- ^ "Artropolis". Merchandise Mart Properties, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on March 15, 2008. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "An Old Maestro's Magic". Time. August 25, 1967. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Zeldes, Leah A. (July 26, 2010). "The Picasso put Chicago in a pickle". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Archived from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ "Pablo Picasso – Other Works – Art Gallery Svetlana & Lubos Jelinek". Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ "Chicago...Picasso...Anubis?". 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Persky, Mort (January 27, 2012). "Inch by Column Inch". Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ^ Coren, Stanley. "Muse and mascot: the artist's life-long love affair with his canine companions". Modern Dog. Archived from the original.

- ^ Wilson, Simon (1994) Picasso: Sculptor/Painter, A Brief Guide, London: Tate Gallery.

- ^ Rubin, William (ed) (1996) Picasso and portraiture: representation and transformation, New York: Museum of Modern Art, plate, p.475.

- ^ Stratton, Patricia S., "The Chicago Picasso: A Point of Departure (Chicago: Ampersand, Inc., 2017).

- ^ Mailer, Norman. Miami and the Siege of Chicago: An Informal History of the Republican and Democratic Conventions of 1968. New York: New American Library, 1968.

References

[edit]- Herrmann, Andrew, "The Woman Who Inspired City's Picasso", Chicago Sun-Times (November 11, 2004)

- Artner, Alan G., "Chicago's Picasso sculpture: The unveiling of the puzzling sculpture changes the public art landscape". Chicago Tribune (August 15, 1967)

- Stratton, Patricia S. "The Chicago Picasso: A Point of Departure" (Chicago: Ampersand Inc., 2017).