Chase Strangio

Chase Strangio | |

|---|---|

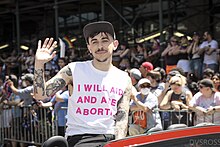

Strangio in 2022 | |

| Born | October 29, 1982 |

| Education | Grinnell College (BA) Northeastern University (JD) |

| Employer | American Civil Liberties Union |

| Known for | Transgender rights activism |

| Children | 1 |

Chase Strangio (/strænˈdʒiːoʊ/[1] born October 29, 1982)[2] is an American lawyer and transgender rights activist. He is the deputy director for transgender justice[3] and staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).[4][5] He is the first known transgender person to make oral arguments before the Supreme Court of the United States.[6]

Early life and education

Strangio grew up in a Jewish family outside of Boston, Massachusetts.[7]

Strangio attended Grinnell College, graduating in 2004.[8] After graduation, he worked as a paralegal at GLBTQ Legal Advocates & Defenders (GLAD).[5][7] He went on to attend Northeastern University School of Law.[9][8] Strangio came out as a transgender man while in law school.[7]

After graduating from Northeastern in 2010, Strangio received a fellowship from the Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP) to continue developing his legal skills.[5]

Career and activism

After law school, Strangio worked as a public defender for Dean Spade, the first openly trans law professor in the U.S.[7] Spade's work had inspired Strangio while he was in college.[5]

In 2012, Strangio and trans activist Lorena Borjas founded the Lorena Borjas Community Fund to provide bail and bond assistance to trans people.[9][5]

In 2013, Strangio began working for the ACLU.[8] Strangio served as lead counsel for the ACLU team representing transgender U.S. Army soldier Chelsea Manning.[4][5] He was also part of the team suing on behalf of trans student Gavin Grimm, who was denied access to the boys' restrooms at his school.[4][10]

In October 2019, Strangio was one of the lawyers representing Aimee Stephens, a trans woman who was fired from her job at a funeral home, in the U.S. Supreme Court case R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Those oral arguments were heard alongside Bostock v. Clayton County, on which Strangio was also a lawyer.[11][12] The previous month, trans actress Laverne Cox brought Strangio as her date to the 2019 Emmy Awards, and the pair spoke to reporters on the red carpet about the upcoming court case.[13][14][15]

In June 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court decided 6–3 in favor of Gerald Bostock, a gay man terminated from his job due to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, in Bostock v. Clayton County. The court ruled that it is illegal to discriminate in employment on the basis of transgender identity or sexual orientation.[16][17]

In November 2020, journalist Glenn Greenwald criticized Strangio's comments about the book Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters by Abigail Shrier. Strangio, who had tweeted that "stopping the circulation of this book and these ideas is 100% a hill I will die on," responded that he was not speaking for the ACLU and said he deleted his tweet because "there were relentless calls to have me fired, which I found exhausting as I was navigating work and childcare."[18][19] According to the New York Times, Strangio's tweet had "startled traditional backers [of the ACLU], who remembered its many fights against book censorship and banning".[20]

Strangio has appeared on television programs including The Rachel Maddow Show,[21] Democracy Now!,[22] For the Record with Greta,[23] AM Joy,[24] PBS NewsHour,[25] and Up.[26]

Since 2021, Strangio has worked with the ACLU to fight against state legislation seeking to prohibit children from accessing treatment for gender transition.[27] On December 4, 2024, he became the first known transgender person to make oral arguments before the Supreme Court of the United States in United States v. Skrmetti, a case brought to challenge a Tennessee law prohibiting certain forms of gender-affirming care (including puberty blockers and hormone therapy) for transgender minors.[28][29] In the days ahead of oral arguments, Strangio published an op-ed in the New York Times describing how having access to the forms of gender-affirming medical care prohibited by the Tennessee law saved his own life.[30]

Honors and recognition

In 2014, Strangio was named to the Trans 100 list for "outstanding contributions to the trans community".[31][32]

In June 2017, Strangio was one of those chosen for NBC Out's inaugural "#Pride30" list.[4]

In May 2018, Strangio was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws by his alma mater Grinnell College.[33]

In November 2019, he was awarded the American Bar Association's Commission on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity's 2020 Stonewall Award.[34]

Strangio was included in 2020's Time 100 most influential people in the world.[35]

Personal life

His partner is the art curator and writer Kimberly Drew (as of 2021).[36] As of 2022, Strangio lives in New York City and has one child.[27]

References

- ^ "Love Is: Revolutionary Joy | Chase Strangio". Uninterrupted. June 12, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ Strangio, Chase (October 29, 2021). ""Made it to 39"". Instagram. Archived from the original on 2021-12-25. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ "Chase Strangio". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ a b c d Compton, Julie (June 7, 2017). "#Pride30: ACLU Lawyer Chase Strangio Is Fighting for Trans Justice". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 19, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Tourjee, Diana (September 27, 2016). "The Trans Lawyer Fighting to Keep Her Community Alive". Broadly. Vice. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ Groppe, Maureen. "Transgender lawyer makes history, takes case on puberty blockers and hormone therapy to Supreme Court". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ a b c d Michaels, Samantha (May 2017). "Chelsea Manning's Lawyer Knows How to Fight Transgender Discrimination—He's Lived It". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Transforming Trans Justice". Grinnell College. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Chase Strangio". American Civil Liberties Union. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ Gordon-Loebl, Naomi (November 9, 2018). "Trump's War on Trans Rights: A Q&A With Chase Strangio". The Nation. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Wakefield, Lily (October 15, 2019). "The trans lawyer who defended trans rights in the landmark Supreme Court case has a sobering warning". PinkNews. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Fitzsimons, Tim (2019-10-09). "Central figures in Supreme Court LGBTQ discrimination cases speak out". NBC News. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

- ^ Fratti, Karen (September 22, 2019). "Laverne Cox's 2019 Emmys Date Is Bringing Attention To A Vital Court Case". Bustle. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ Vanderhoof, Erin (September 23, 2019). "Emmys 2019: Laverne Cox's Political Rainbow Purse Had a Secret Message". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ McDermott, Maeve (September 22, 2019). "Emmys 2019: Laverne Cox's clutch has an important pro-LGBTQ message". USA Today. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- ^ "What landmark Supreme Court ruling means for LGBTQ rights". PBS NewsHour. 2020-06-15. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ "Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ Greenwald, Glenn (November 15, 2020). "The Ongoing Death of Free Speech: Prominent ACLU Lawyer Cheers Suppression of a New Book". Substack. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ "'Mighty' Ira Glasser & the ACLU Foundation". Tablet Magazine. 2021-03-31. Retrieved 2021-06-27.

- ^ Powell, Michael (2021-06-06). "Once a Bastion of Free Speech, the A.C.L.U. Faces an Identity Crisis". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-07-04.

- ^ "Discrimination law puts North Carolina in legal hot seat". The Rachel Maddow Show. March 28, 2016. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "Shows featuring Chase Strangio". Democracy Now. Archived from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "Chelsea Manning's Attorney: 'This Has Saved Her Life'". MSNBC. January 17, 2017. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "Transgender rights under fire in Trump era". MSNBC. February 25, 2017. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ Feliciano, Ivette (January 12, 2019). "Is banning trans troops a legal tactic to reverse civil rights?". PBS NewsHour. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Gura, David (October 6, 2019). "Laverne Cox: We exist, we deserve human rights". Up with David Gura. MSNBC. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Larson, Erik (March 16, 2022). "This Lawyer Is Fighting a Deeply Personal Battle for Trans Rights". Bloomberg News. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ Hansford, Amelia (2024-12-03). "Trans attorney Chase Strangio to make Supreme Court history". PinkNews. Retrieved 2024-12-04.

- ^ Stein, Chris (December 4, 2024). "Supreme court begins hearing major case on trans youth healthcare ban – live". The Guardian. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Strangio, Chase (December 3, 2024). "May It Please the Court: Trans Health Saved My Life". The New York Times. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ "SRLP's Gabriel Foster, Chase Strangio and Bali White honored by the Trans 100!". Sylvia Rivera Law Project. April 7, 2014. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "Trans 100 2014" (PDF). The Trans 100. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- ^ "Commencement 2018 Is Complete | Grinnell College". www.grinnell.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2018-05-22.

- ^ "ACLU attorney Chase Strangio to receive 2020 Stonewall Award". www.americanbar.org. Retrieved 2020-06-19.

- ^ "Chase Strangio: The 100 Most Influential People of 2020". Time. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

- ^ "Also.Also.Also: Chase Strangio and Kimberly Drew Are the Cutest Queer Love Story You'll See Today!". 23 March 2021.

Further reading

- Gessen, Masha. "Chase Strangio's Victories for Transgender Rights". The New Yorker. October 12, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

External links

- Living people

- 1982 births

- American Civil Liberties Union people

- Grinnell College alumni

- Lawyers from Boston

- American LGBTQ lawyers

- American LGBTQ rights activists

- American transgender men

- Northeastern University School of Law alumni

- Transgender rights activists

- LGBTQ people from Massachusetts

- LGBTQ Jews

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people

- 21st-century American LGBTQ people

- Activists from Boston

- 21st-century American lawyers