Chanois Coal Mine

| |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Coordinates | 47°41′33″N 06°37′44″E / 47.69250°N 6.62889°E[1] |

| Production | |

| Products | Coal |

| Type | Coal mine |

| Greatest depth | 588 m (1,929 ft) |

| History | |

| Discovered | 1873 |

| Opened | August 25th,1873 |

| Active | 1895–1951 |

| Closed | 1958 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Ronchamp coal mines, Électricité de France group |

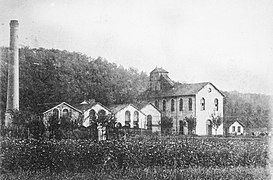

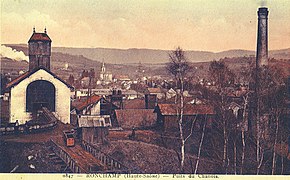

The Chanois coal mine is one of the main shafts of the Ronchamp coal mines, in the French commune of Ronchamp, within the Haute-Saône department, belonging to the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region. It was the center of Ronchamp's coal mining operations from the late 19th century until the mines closed in 1958. It was therefore chosen as the site for the coal mine's ancillary facilities, including a coal preparation plant, a coking plant, and a power station. It succeeded the Saint Joseph shaft in 1895 and ceased mining in 1951.

At the beginning of the 21st century, many remnants of these facilities (ruins, a large concrete hopper, converted buildings, and two imposing spoil tips) remain.

Excavation

[edit]Before 1873, the Ronchamp coal mining company operated in the center of the Ronchamp and Champagney coalfields. But the shafts used for this task reached the end of their production life and had to be replaced. This was the role of the Magny and Chanois shafts.[2]

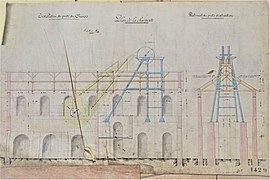

Excavation of the latter began on August 25, 1873, with a useful diameter of 3.20 meters. The ventilation shaft was sunk 25 meters from the former, with a diameter of 2.20 meters. A 120-meter-high casing was added to mitigate the 300 hectoliters-per-hour inflow of water. In addition to the casing, Neut et Dumont pumps were installed.[2]

On February 16, 1877, the shaft encountered coal at depths of 580 meters, but the layer was unusable. The drilling stopped at 588 meters in the transitional ground. Research was made impossible by heavy water inflows, and the shaft remained inactive until 1895.[2]

Exploitation

[edit]Mining began in the 20th century, with production rising steadily from 100 tonnes a day in 1895 to 250 tonnes a day in 1900,[3] and finally reaching 12,587 tonnes in 1901. Following restoration, the 120 hp[4] Sainte-Pauline[2] shaft winding engine was installed on the site, using special aloe wire ropes. This type of cable was used until the end of operations.[2] The recette jour building was installed more than six meters above ground level, as evidenced by old postcards, plans, and the wide stone wall visible until 2014.[5]

The compressed air used at the Magny and Chanois wells was generated by two Burckardt compressors and an older Sommeiller compressor. By 1897, these had to be replaced by new five-cubic-meter compressors powered by a 150-horsepower steam engine.[6]

In 1902, a pump and electric lighting were installed at the bottom.[7] Between 1904 and 1910, a fire raged at the bottom of the mine, causing no casualties.[2]

In 1928, an assembly was dug to the Sainte Marie Coal Mine, and in 1929, the 1,500-meter-long "Cameroun" bowette (rock tunnel) linked it to the Notre-Dame shaft. These two shafts still had exploitable coal seams, but were not equipped for extraction.[5] In 1933, the steam engine was replaced by an electric one.[8]

When the French coal industry was nationalized in 1946, under the impetus of the Provisional Government led initially by Charles de Gaulle, the Ronchamp coalfield was entrusted to Électricité de France (EDF), as it was too far from the other major coalfields and included a major thermal power station.[9]

The Chanois shaft closed in 1951, before the Arthur de Buyer Coal Mine. In 1958, both shafts were backfilled with shale and covered with a concrete slabs.[2][10]

Reconversion

[edit]After closure, the installations were dismantled, and the muffler and air compressor were reassembled on the Etançon shaft.[11] The buildings were demolished between 1960 and 1963 to make way for the Germinal housing estate, comprising three blocks of flats.[12] All that remains is the ruined extraction building and the lamp factory, which retains its roof. The extraction building was finally demolished in 1980.[13]

In the 2000s, the ruins consisted of the dilapidated lamproom building, a remnant wall from the well building, and several blocks of masonry and concrete in a wasteland strewn with bricks and stones.[5] From 2011 to 2013, a construction site for six pavilions required the destruction of several remnants.[14] One of the three buildings of the Germinal housing estate was also demolished following authorization obtained on November 15, 2012.[15]

- The worksite in February 2013.

-

The shaft wall.

-

View of the Germinal company town.

-

Location of a future home.

-

Brick from old buildings.

-

Remains of a building.

-

Location of a former compressor .

In 2013, only a section of the wall of the recette jour building and the lamppost building remained intact, next to the housing estate built on the site of several of the pit's buildings.

As of 2014, this wall no longer exists.

Annex facilities

[edit]

The sorting-washing-screening workshops were built in 1898, replacing the small workshops from the Magny shaft. A coking plant was built between 1900 and 1920 to replace the furnaces in the Saint-Joseph shaft. It closed in 1933, while the rest of the installations remained in operation until the mines closed in 1958. The power station was operated by the Ronchamp coal mines from its construction between 1906 and 1907 until its nationalization in 1946, when it became the property of Électricité de France until its closure in 1958. The plant was expanded twice between 1910 and 1924, to reach a capacity of 30 MW. Annual production varied between 5 and 37 GWh until 1950.[16] A few ruins of these installations (including one hopper) remained at the beginning of the 21st century,[17] whereas the second hopper was dynamited by the army in the 1960s and left in place.[18]

The company town

[edit]The mining company town was built, in 1919, after World War I, initially to accommodate troops, before being used between 1923 and 1925 to house Polish immigrants. It consisted of small, temporary barracks that were still inhabited after the mine closed.[19][20] During the nationalization of the mine, the housing estate was the property of EDF, then taken over by the municipality, which rehoused the inhabitants elsewhere. It was demolished in early 1976 and replaced by a housing project in the northern part and a low-cost apartment (HLM) block in the southern part.[21]

The spoil tips

[edit]47°41′36″N 6°37′49″E / 47.69333°N 6.63028°E

Formation in mining times

[edit]The Chanois shaft had a coal preparation plant, which also received products from the Magny and Arthur de Buyer Coal Mine, as well as the Etançon outcrops. As a result, there are numerous conical and flat slag heaps around these facilities, located on the Chanois plain.[22] Before their exploitation in 2010, the total volume of mine waste was estimated at 1 million tonnes.[23] Some of these spoil tips undergo spontaneous internal combustion over several decades, giving them a red color.[24]

Exploitation

[edit]These slag heaps, still rich in coal, were exploited by the Escaut-Énergie company between March 1985 and December 1986.[25] Most of the slag heaps on the Chanois plain have disappeared (exploited as a quarry),[26] particularly those near the shaft.[27]

On May 17, 2010, the Prefect of Haute-Saône authorized the exploitation of the slag heap's shales as a quarry by the limited company GDFC (granulats de Franche-Comté), on condition that the protected natural environments remain intact and that the historic sites are respected (certain slag heaps, buildings and the concrete hopper).[28] The same company had already been operating the slag heap ("Le Triage") since 1994.[29]

- Remains of Escaut-Énergie facilities.

Fossils

[edit]The spoil tips contain numerous fossils dating back to the Carboniferous period, and are unique because they group together plants living in a dry, mountain environment (Blackthorn, Ferns, Cordaites, and the first flowering plants, which are only found in the most recent layers) and in marshy lowland environments (Lepidodendron buttercup, Sigillaria, Calamites, Sphenophyllum), as well as freshwater fish.[30]

Natural area

[edit]In the early 2000s, the SMPM association carried out an inventory of the mycoflora on the Chanois slag heaps area, which had been overtaken by birch and willow, discovering several rare species such as Pisolithus arhizus, Lactarius fuscus, and Stropharia rugosoannulata, demonstrating the importance of conserving these slag heaps. On June 19, 2007, the Ronchamp town council officially announced the conservation of the north-western section of the Plaine du Chanois slag heaps and those of the Etançon mine shaft.[31][32] At the same time, the non-vegetated part of the site (nicknamed the "crassier") is regularly used for motocross, but this is prohibited by the Ronchamp town council due to the noise pollution it causes, offenders risk a €135 fine and confiscation of the motorcycle and its transport vehicle.[33]

-

The red slag heap (Ronchamp) on the left and the black slag heap (Magny-Danigon) on the right.

-

Red slag heap (Ronchamp).

-

The quarried slag heap (Magny-Danigon).

-

Exploited area.

Reception area for travellers

[edit]From 2013 to 2014, the Rahin et Chérimont Community of Communes built a reception area for Travellers to the northeast of the remaining slag heaps, next to the former coking plant. It includes eight parking areas of 80 m2 each, and three platforms for long-stay travelers, with a total usable surface area of 9,200 m2.[34][35]

-

The formation of the red slag heap

-

The quarried slag heap near the shaft

-

Travellers' reception area

-

The three platforms

Photovoltaic plant

[edit]In 2021, a project to build a 5.9-hectare photovoltaic power plant on the Chanois slag heaps was initiated jointly by the communes of Ronchamp and Magny-Danigon, with the support of the Rahin et Chérimont Communauté de Communes and the Pays de Lure Communauté de Communes, in collaboration with TotalEnergies and Altergie. The plant is to be located in two zones: the Ronchamp zone (2.6 hectares) will be set up at the top of the red slag heap, near the Chanois well and the former coal-fired power station -whose former substation will be used for power distribution- and the Magny-Danigon zone (3.3 hectares) will be located on the former slag heap sorted by Escaut-Énergie and mined for aggregates. Work is scheduled to start in 2023–2024, with commissioning scheduled for 2025. The project comprises a total of 9,256 potential modules with a maximum output of 4.99 MWp, enough to cover the electricity consumption of 3,480 inhabitants.[36][37][38]

References

[edit]- ^ – Puits du Chanois [1]. BRGM is the leading French public body in the field of earth sciences for the management of soil and subsoil resources and risks.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Les puits de Ronchamp" archive, on Les Amis du Musée de la Mine (accessed August 7, 2012).

- ^ Jean-Jacques Parietti 1999 (2), p. 15.

- ^ Édouard Thirria 1869, p. 186.

- ^ a b c "Le puits du Chanois" archive, on Les Amis du Musée de la Mine (accessed on August 7, 2012).

- ^ Jean-Jacques Parietti 1999 (2), p. 11.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Parietti 2001, p. 48.

- ^ "La machine électrique" archive, on Les Amis du Musée de la Mine.

- ^ Parietti 2001, p. 73.

- ^ Parietti et Petitot 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Parietti 2017, p. 17.

- ^ "Vue sur la cité Germinal " archive, on abamm.org.

- ^ Aerial photography missions available on Géoportail by year.

- ^ "Le Chanois and Recologne under the microscope" archive, on Le Pays.

- ^ "La démolition de l'immeuble actée" archive, on L'Est républicain.

- ^ "Les ateliers dans la plaine du Chanois" archive, on Les Amis du Musée de la Mine (accessed August 8, 2012).

- ^ Alain Banach, "Les vestiges du triage Archived 2023-01-29 at the Wayback Machine" archive, on Les Amis du Musée de la Mine (accessed December 19, 2020).

- ^ (fr) "La trémie dynamitée" archive.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Parietti 2010, p. 101.

- ^ "La cité du Chanois" archive.

- ^ "Les corons du quartier du Chanois Archived 2023-03-25 at the Wayback Machine" [archive].

- ^ "Image des terrils" archive.

- ^ "Les terrils du bassin houiller de Ronchamp et Champagney" archive, on abamm.org (accessed on September 5, 2015).

- ^ "Le terril rouge" archive.

- ^ "Escaut-Énergie in Magny-Danigon" archive.

- ^ "The disappearance of the spoil heaps" archive.

- ^ "Les terrils aujourd'hui disparus" archive.

- ^ "Autorisation d'exploitation des terrils du Chanois" archive [PDF], on haute-saone.gouv.fr.

- ^ DREAL Franche-Comté, "Études préalables à la révision des quatre schémas départementaux des carrières Archived 2011-09-08 at the Wayback Machine" archive Archived August 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine [PDF], on franche-comte.developpement-durable.gouv.fr, March 2011.

- ^ [PDF] Yves Clerget, Once upon a time... an ancient landscape: the Ronchamp coal-mining forest, Educational Service of the Cuvier Museum in Montbéliard (read online [][http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.mineronchamp.fr%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2014%2F12%2F3For--tHouill--re-Rchp2018.pdf archive] Archived January 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Les terrils de Ronchamp : de la banalisation au sentier d'interprétation, SMPM (read online).

- ^ [PDF] Liste rouge des champignons supérieurs de Franche-Comté, DREAL Franche-Comté, 2013 (read online Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine archive Archived August 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine), p. 18.

- ^ "Le crassier de Ronchamp" archive, on ronchamp.fr (accessed on September 5, 2015).

- ^ "L'aire d'accueil des gens du voyage alimentée en électricité" archive, on L'Est républicain, January 7, 2014 (accessed September 2, 2015).

- ^ [PDF] Communauté de communes Rahin et Chérimont, Création d'une aire d'accueil pour les Gens du voyage et d'une aire de grand passage, Ronchamp, January 7, 2013 (read online Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine archive Archived August 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Ch.L., "Une centrale photovoltaïque sur l'ancien terril" archive, in L'Est républicain, January 29, 2020 (accessed November 14, 2021).

- ^ "Une centrale photovoltaïque sur les terrils en projet" archive, in L'Est républicain, November 7, 2021 (accessed November 14, 2021).

- ^ Guillaume Minaux, "Une centrale solaire en projet près de Lure" archive, in L'Est républicain, December 11, 2021 (accessed December 15, 2021).

See also

[edit]Related articles

[edit]- fr:Mining in France

- Ronchamp coal mines

- Mining basin of Ronchamp and Champagney

- Thermal power station of Ronchamp

- fr:Chanois coking and washing plant

External links

[edit]- "Friends of the Mine Museum website" archive*"Le puits du Chanois" archive, on http://www.abamm.org/

- "Le ateliers du ChanoisArchived 2022-05-29 at Wikiwix" archive, on http://www.abamm.org/ archive

- "Old postcards from the Chanois shaft" archive, on http://jtaiclet.free.fr/ archive Ronchamp in the last century.

- "Old postcards from the Chanois workshops" archive, on http://jtaiclet.free.fr/ archiveArchived November 22, 2018, at Wikiwix Ronchamp in the last century.

- "Old postcards of the power plant" archive, on http://jtaiclet.free.fr/ archive Ronchamp in the last century.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jean-Jacques Parietti, Les Houillères de Ronchamp vol. I: La mine, Vesoul, Éditions Comtoises, 2001, 87 p. (ISBN 2-914425-08-2).

- Jean-Jacques Parietti, Les Houillères de Ronchamp vol. II: Les mineurs, Noidans-lès-Vesoul, fc culture & patrimoine, 2010, 115 p. (ISBN 978-2-36230-001-1)

- Jean-Jacques Parietti, Les dossiers de la Houillère 1: Le puits Sainte marie, Association des amis du musée de la mine, 1999 (read online archive).

- Jean-Jacques Parietti, Les dossiers de la Houillère 5: Le puits du Magny, Association des amis du musée de la mine, 1999 (2).

- Jean-Jacques Parietti, Les dossiers de la Houillère 6: Le puits de l'Étançon, Association des amis du musée de la mine, 2017.

- Jean-Jacques Parietti and Christiane Petitot, Géomètre aux houillères de Ronchamp, Association des amis du musée de la mine, 2005.

- Conseil général du Territoire de Belfort, Vivre le Territoire : Le magazine de conseil général du Territoire de Belfort, Belfort, October 2013, 142nd ed., 31 p.

- Édouard Thirria, Manuel à l'usage de l'habitant du département de la Haute-Saône, 1869 (read online archive), p. 182–186.