Caenagnathidae

| Caenagnathids Temporal range: Early-Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skull of Anzu wyliei | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Caenagnathoidea |

| Family: | †Caenagnathidae Sternberg, 1940 |

| Type species | |

| †Caenagnathus collinsi Sternberg, 1940

| |

| Genera | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Caenagnathidae is a family of derived caenagnathoid dinosaurs from the Cretaceous of North America and Asia. They are a member of the Oviraptorosauria, and relatives of the Oviraptoridae.[2] Like other oviraptorosaurs, caenagnathids had specialized beaks,[3] long necks,[4] and short tails,[5] and would have been covered in feathers. The relationships of caenagnathids were long a puzzle. The family was originally named by Raymond Martin Sternberg in 1940 [6] as a family of flightless birds. The discovery of skeletons of the related oviraptorids revealed that they were in fact non-avian theropods,[7] and the discovery of more complete caenagnathid remains [4][8] revealed that Chirostenotes pergracilis, originally named on the basis of a pair of hands, and Citipes elegans, originally thought to be an ornithomimid, named from a foot, were caenagnathids as well.

Discovery

[edit]The name Caenagnathus (and hence Caenagnathidae) means "recent jaws"—when first discovered, it was thought that caenagnathids were close relatives of paleognath birds (such as the ostrich) based on features of the lower jaw. Since it would be unusual to find a recent group of birds in the Cretaceous, the name "recent jaws" was applied. Most paleontologists, however, now think that the birdlike features of the jaw were acquired convergently with modern birds.[9][10]

Description

[edit]

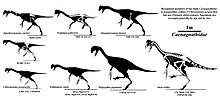

Caenagnathids were some of the largest oviraptorosaurs that ever existed. The largest members are represented by the enormous Beibeilong and Gigantoraptor, estimated around 7.5–8 m (25–26 ft) in length.[11][12][13] Other caenagnathids were slightly smaller, such as the 3 m (9.8 ft) long Hagryphus,[14] or the 3.5 m (11 ft) long Anzu.[15]

Overall, the anatomy of the caenagnathids is similar to that of the closely related Oviraptoridae, but there are a number of differences. In particular, caenagnathid jaws exhibited a distinct suite of specializations not seen in other oviraptorosaurs. Compared to the oviraptorids, the jaws tended to be relatively long and shallow, suggesting that the bite was not as powerful. The inside of the lower jaws also bore a complex series of ridges and toothlike processes, as well as a pair of horizontal, shelf-like structures. Furthermore, the jaws were unusual in being hollow and air filled, apparently being connected to the air sac system.[3]

Analysis of oviraptorosaur functional morphology reveals that caenagnathids were not as well suited to herbivory as more primitive oviraptorosaurs, and their close relatives, the oviraptorids. Their mandibles have a lower mechanical advantage anteriorly but not posteriorly, similar to the dromaeosaurids, and are less robust, which makes them more suited to quicker prey capture, with their pointed beaks aiding in slashing prey.[16]

Caenagnathids also tended to be more lightly built than the oviraptorids. They had slender arms and long, gracile legs,[8] although they lacked the extreme cursorial specializations seen in avimimids and Caudipteryx.

Classification

[edit]The family Caenagnathidae, together with its sister group the Oviraptoridae, comprises the superfamily Caenagnathoidea. In phylogenetic taxonomy, the clade Caenagnathidae is defined as the most inclusive group containing Caenagnathus collinsi but not Oviraptor philoceratops.[17] While before 2010s only about two to six species were commonly recognized as belonging to the Caenagnathidae, currently that number may be much greater, with new discoveries and theories about older species that may inflate this number to up to ten. Much of this historical difference centers on the first caenagnathid to be described, Chirostenotes pergracilis. Due to the poor preservation of most caenagnathid remains and resulting misidentifications, different bones and different specimens of Chirostenotes have historically been assigned to a number of different species. For example, the feet of one species, named Macrophalangia canadensis,[18] were known from the same region from which Chirostenotes pergracilis was recovered, but the discovery of a new specimen with both hands and feet preserved[8] provided the support to combine them, while the later discovery of a partial skull with hands and feet [4] suggested that Chirostenotes and Caenagnathus were the same animal, and current studies of caenagnathid relationships continue to find them as closely related genera.[19]

Hendrickx and colleagues (2015) defined a subgroup of Caenagnathidae, the Caenagnathinae, as all caenagnathids more closely related to Caenagnathus collinsi than to Elmisaurus rarus.[20] The group Elmisaurinae is defined as including all species more closely related to Elmisaurus rarus than to Caenagnathus collinsi.[20][21]

The cladogram below follows an analysis by Gregory Funston in 2020.[22]

| Caenagnathidae | |

Evolution

[edit]

The earliest known caenagnathid is Microvenator celer, from the Early Cretaceous Cloverly Formation. Caenagnathids likely dispersed to Asia from North America with some caenagnathids later reappearing in western North America, during the Campanian. Caenagnathids showed considerable variation in form. The tiny jaws of Caenagnathasia suggest a small animal, perhaps the size of a turkey. Anzu wyliei, from the Hell Creek Formation is a much larger animal, considerably larger than a human. If Gigantoraptor erlianensis is a caenagnathid, then it would represent far and away the largest member of the group, measuring up to 8 meters (26 ft) in length and weighing up to 2 metric tons (2.2 short tons).[23]

Their beaks also show considerable variation; that of Caenagnathasia is relatively short and deep, while that of Caenagnathus is long and shovel-shaped. This variation in size and beak shape suggests that caenagnathids evolved to exploit a range of ecological niches. Caenagnathids persisted up until the end of the Cretaceous period, as shown by the presence of Anzu and another, unnamed species of elmisaurine (all caenagnathids closer to Elmisaurus than to Caenagnathus) in the late Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation, before vanishing at the end of the Cretaceous along with all other non-avian dinosaurs.[15]

Species

[edit]Roughly a dozen caenagnathid species have been named, but it remains unclear how many are valid. Many species are known from fragmentary remains, such as jaws, hands, or feet, making comparisons between them difficult. Caenagnathus sternbergi, for example, was described on the basis of a jaw bone. It has been interpreted as either the jaws of Chirostenotes pergracilis (described on the basis of a pair of hands) or Chirostenotes elegans[4] (described on the basis of a foot), but because no complete skeleton is known, it is difficult to be certain which animal it belongs to. The relationships of other species remain in doubt. Gigantoraptor was originally interpreted as an oviraptorid, but may in fact represent a primitive caenagnathid.[24]

- Anzu wyliei - (Hell Creek Formation, North Dakota and South Dakota, United States)[15]

- Apatoraptor pennatus - (Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Alberta)

- Beibeilong sinensis - (Gaogou Formation, China)[12]

- Caenagnathasia martinsoni - (Bissekty Formation, Uzbekistan)

- Citipes elegans - (Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada)

- Chirostenotes pergracilis - (Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada)

- Caenagnathus collinsi - (Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada)

- Elmisaurus rarus - (Nemegt Formation, Mongolia)

- Eoneophron infernalis - (Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota)

- Epichirostenotes curriei - (Horseshoe Canyon Formation, Alberta, Canada)

- Gigantoraptor erlianensis - (Iren Dabasu Formation, Inner Mongolia, China)

- Hagryphus giganteus - (Kaiparowits Formation, Utah, United States)

- Leptorhynchos gaddisi - (Aguja Formation, Texas, United States)[19]

- Nomingia gobiensis - (Nemegt Formation, Mongolia)

- Ojoraptorsaurus boerei - (Ojo Alamo Formation, New Mexico, United States)

Caenagnathids are only known from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia.[25] The earliest and most primitive known caenagnathid is Caenagnathasia martinsoni, from the Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Atkins-Weltman, K. L.; Simon, D. J.; Woodward, H. N.; Funston, G. F.; Snively, E. (2024). "A new oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the end-Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation of North America". PLOS ONE. 19 (1). e0294901. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0294901. PMC 10807829.

- ^ Osmólska, H., P. J. Currie, et al. (2004). Oviraptorosauria. The Dinosauria. D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson and H. Osmolska. Berkeley, University of California Press: 165-183.

- ^ a b Currie, P. J.; Godfrey, S. J.; et al. (1993). "New caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) specimens from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10–11): 2255–2272. Bibcode:1993CaJES..30.2255C. doi:10.1139/e93-196.

- ^ a b c d Sues, H. D. (1997). "On Chirostenotes, a Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from western North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (4): 698–716. Bibcode:1997JVPal..17..698S. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011018.

- ^ Barsbold, R.; Osmolska, H.; Watabe, M.; Currie, P. J.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (2000). "New oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Mongolia: The first dinosaur with a pygostyle" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 45 (2): 97–106.

- ^ Sternberg, R.M. (1940). "A toothless bird from the Cretaceous of Alberta". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (1): 81–85.

- ^ Osmólska, H (1976). "New light on the skull anatomy and systematic position of Oviraptor". Nature. 262 (5570): 683–684. Bibcode:1976Natur.262..683O. doi:10.1038/262683a0. S2CID 4180155.

- ^ a b c Currie, P.J.; Russell, D.A. (1988). "Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River Oldman Formation of Alberta". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 25 (3): 972–986. doi:10.1139/e88-097.

- ^ Cracraft, J. (1971). "Caenagnathiformes: Cretaceous birds convergent in jaw mechanism to dicynodont reptiles". Journal of Paleontology. 45: 805–809.

- ^ Barsbold, R., Maryańska, T., and Osmólska, H. (1990). "Oviraptorosauria." pg. 249-258 in Weishampel, Dodson, and Osmolska (eds.) The Dinosauria, University of California Press (Berkeley).

- ^ Xing, X.; Tan, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Tan, L. (2007). "A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of China". Nature. 447 (7146): 844−847. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..844X. doi:10.1038/nature05849. PMID 17565365. S2CID 6649123. Supplementary Information

- ^ a b Pu, H.; Zelenitsky, D. K.; Lü, J.; Currie, P. J.; Carpenter, K.; Xu, L.; Koppelhus, E. B.; Jia, S.; Xiao, L.; Chuang, H.; Li, T.; Kundrát, M.; Shen, C. (2017). "Perinate and eggs of a giant caenagnathid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of central China". Nature Communications. 8 (14952): 14952. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814952P. doi:10.1038/ncomms14952. PMC 5477524. PMID 28486442. Supplementary Information.

- ^ Engelhaupt, E. (2017). "'Baby Dragon' Dinosaur Found Inside Giant Egg". National Geographic. Culture & History.

- ^ Zanno, L. E.; Sampson, S. D. (2005). "A new oviraptorosaur (Theropoda; Maniraptora) from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 897–904. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0897:anotmf]2.0.co;2. S2CID 131302174.

- ^ a b c Lamanna, M. C.; Sues, H.-D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014). "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e92022. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...992022L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022. PMC 3960162. PMID 24647078.

- ^ Pittman, Michael; Xu, Xing (2020-08-21). "Pennaraptoran Theropod Dinosaurs Past Progress and New Frontiers". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 440 (1): 1. doi:10.1206/0003-0090.440.1.1. ISSN 0003-0090.

- ^ Sereno, Paul C. (1998-11-10). "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria [41-83 ]". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 210 (1): 41–83. doi:10.1127/njgpa/210/1998/41. ISSN 0077-7749.

- ^ Sternberg, C. H. (1932). "Two new theropod dinosaurs from the Belly River Formation of Alberta". The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 46: 99–105.

- ^ a b Longrich, N. R.; Barnes, K.; Clark, S.; Millar, L. (2013). "Caenagnathidae from the Upper Campanian Aguja Formation of West Texas, and a Revision of the Caenagnathinae". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 54: 23–49. doi:10.3374/014.054.0102. S2CID 128444961.

- ^ a b Hendrickx, Christophe; Hartman, Scott A.; Mateus, Octávio (2015). "An overview of non-avian theropod discoveries and classification" (PDF). PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 12 (1): 1–73.

- ^ Currie, P.J.; Funston, G.F.; Osmólska, H.† (2015). "New specimens of the crested theropod dinosaur Elmisaurus rarus from Mongolia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (1): 143–157 (2014–2016). doi:10.4202/app.00130.2014. S2CID 55254194.

- ^ Funston, Gregory (2020-07-27). "Caenagnathids of the Dinosaur Park Formation (Campanian) of Alberta, Canada: anatomy, osteohistology, taxonomy, and evolution". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 8: 105–153. doi:10.18435/vamp29362. ISSN 2292-1389.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2010). "Theropods". The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 67–162. doi:10.1515/9781400836154.67b. ISBN 9781400836154.

- ^ Nicholas R. Longrich; Philip J. Currie; Dong Zhi-Ming (2010). "A new oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia". Palaeontology. 53 (5): 945–960. Bibcode:2010Palgy..53..945L. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00968.x.

- ^ Serrano-Brañas, Claudia Inés; Espinosa-Chávez, Belinda; Maccracken, S. Augusta; Barrera Guevara, Daniela; Torres-Rodríguez, Esperanza (November 2022). "First record of caenagnathid dinosaurs (Theropoda, Oviraptorosauria) from the Cerro del Pueblo Formation (Campanian, Upper Cretaceous), Coahuila, Mexico". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 119: 104046. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2022.104046. Retrieved 11 November 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Currie, P.J.; Godfrey, S.J.; Nesov, L.A. (1994). "New caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) specimens from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10): 2255–2272. Bibcode:1993CaJES..30.2255C. doi:10.1139/e93-196.