Blizna V-2 missile launch site

| |

| |

| Established | 2011 |

|---|---|

| Location | Blizna 68, 39–104 Ocieka, Ropczyce-Sędziszów, Poland |

| Coordinates | 50°11′0″N 21°36′0″E / 50.18333°N 21.60000°E |

| Type | War museum |

| Owner | Gmina Ostrów |

| Website | Park Historyczny Blizna |

| SS-Truppenübungsplatz Heidelager[1] | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

| Commandant | SS Oberführer Bernhardt Voss |

| Killed | 15,000 total: 7,000 Jews, 5,000 Soviets, 3,000 Polish[2][3] |

| Liberated by | Armia Krajowa, Red Army |

The Blizna V-2 missile launch site was the site of a World War II German V-2 missile firing range.[note 1] Today there is a small museum located in the Park Historyczny Blizna (Historical Park) in Blizna, Poland.[4] After the RAF strategic bombing of the V-2 rocket launch site in Peenemünde, Germany, in August 1943, some of the test and launch facilities were relocated to Blizna in November 1943.[5][6] The first of 139 V-2 launches was carried out from the Blizna launch site on 5 November 1943.[7]

History

[edit]After the air raid on Peenemünde on 17 August 1943, German strategic command decided to divide the work on the V-2 rocket among three independently operating centres.[5][6][8][9][10] Assembly plants were transferred to underground factories that had been built in a massive hollow cave complex in the Harz mountains in Germany.[8][11] The research, development, and design (codenamed "Project Cement") were handled by secret offices in Ebensee, near the banks of Lake Traunsee in Austria.[5][8][11] The main rocket testing, training, and launch site was transferred to Blizna in southeast Poland, outside of the range of Allied bombers.[5][8] An SS military base near Blizna was set up on 5 November 1943, from which 139 A4 (also known as V-2) rockets were launched for experimental purposes and for training.[5][7][8][12] The site was operational until early July 1944. Test launches also continued at Peenemünde until 21 February 1945.[6][12]

Before construction began in Blizna, there was nothing there but uncleared forest.[5] The Nazis used slave labour from the nearby SS Truppenübungsplatz Heidelager concentration camp in Pustków to build new infrastructure, starting with concrete roads, then a narrow-gauge railway line linking to the station at Kochanówka village.[5][8][13][14] They built barracks, bunkers, buildings and all the specialised equipment needed for the operation and firing of rockets.[5][8][15] In addition, efforts were made to disguise the site as much as possible. They did this by building an artificial village; cottages and barns were made of plywood, lines were hung with clothes and bed-sheets, and imitation people and animals were created using gypsum plaster.[8][15][9][10]

The site was considered to be of such high strategic importance that it attracted personal visits from many of the Nazi régime's most elite officers;[16] Heinrich Himmler and SS-Obergruppenführers Hans Kammler and Gottlob Berger visited in September 1943,[17] and Adolf Hitler visited in the spring of 1944.[5][8] The commander of the site was Major-General Dr Walter Dornberger, leader of Nazi Germany's V-2 rocket program.[16] Wernher von Braun, creator of the V-2, the central figure in Germany's pre-war rocket development program, and post-war director of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center,[18][19] worked at the Blizna test site and personally visited the test missile impact areas to troubleshoot any problems discovered during trials.[5][8][9][10][12][16][20]

.

British Intelligence were very keen to obtain information about the new V-2 missile site. The first reports came in October 1943 from the Polish underground Home Army (Armia Krajowa) Intelligence HQ in Warsaw, stating that a number of villages around Dębica were being forcibly evacuated.[21] This area was already known for its SS training centre SS-Truppenübungsplatz Heidelager. Further reports brought information about a new railway line being constructed in the same vicinity, leading to Blizna.[21] A report made on 14 February 1944 gave information about a sighting of a rocket "fourteen metres (46 feet) long and [with] a weight of seven tons". On 22 February the report was of a projectile "twelve metres (39 feet) long, [with] a diameter [of] one and a half metres (4.9 feet) and a weight of twelve tons". These missiles were being fired 24 hours a day.[21] The codebreakers at Bletchley Park in England also managed to decrypt vital information from German communications.[22] These made mention of "Versuchsstab (experimental staff) Komanndostelle Siegfried" and of "SS-Truppenübungsplatz Heidelager". Many more communications were intercepted and decrypted, which together with information from the Polish, helped British Intelligence build up a good picture of what was going on.[22][23]

The missile testing ground at Blizna was quickly located by the Polish resistance movement, the Armia Krajowa, thanks to reports from local farmers.[5][24] The site was constantly under observation by Armia Krajowa and the Polish Peasant Battalions.[5][13][25] Due to Blizna's perceived strategic importance, Armia Krajowa (AK) had many field agents operating covertly in the area;[13] these included AK Kolbuszowa (code name: "Kefir"), AK Dębica (code name: "Deser") and AK Mielec (code name: "Mleko").[13][25] These field agents even managed to obtain pieces of the fired rockets, by arriving on the scene before German patrols.[13][26] These fragments were then smuggled by AK agents to secret labs in Warsaw, where the rocket parts were analysed by specialist teams, headed by Professors Marceli Struszyński and Janusz Groszkowski, and glider constructor Antoni Kocjan.[27][28] Vital information about the rocket propellant was discovered when numerous reports came in of a strong smell of alcohol at the crash sites.[26][29][note 2][30] AK agent Aleksander Rusin (code name: "Rusal") was one of these witnesses. A V-2 missile crash-landed near to his observation location near Mielec.[29] Rusin ran up to the crash site and found an intact working motor, which he managed to measure and sketch shortly before it exploded.[26][29]

In early March 1944 British Intelligence Headquarters received a report of an Armia Krajowa agent (code name: "Makara") who had covertly surveyed the Blizna railway line and observed a freight car heavily guarded by SS troops containing "an object which, though covered by a tarpaulin, bore every resemblance to a monstrous torpedo".[13][31] Subsequently, a plan was formed to make an attempt to capture a whole unexploded V-2 rocket and transport it to Britain.[32][33] The plan was to stop the train in the forested area between Brzeskie and Tarnów.[32][33] Despite meticulous planning by Armia Krajowa, the security on the German supply trains had been increased dramatically and the plan had to be called off at the last minute, as it had become unfeasible.[32][33] Around 20 May 1944, a relatively undamaged V-2 rocket fell on the swampy bank of the Bug River near the village of Sarnaki, south of Siemiatycze, and local Poles managed to hide it before Germans arrived.[34] The rocket was then dismantled and smuggled across Poland.[34][35] During the night of 25–26 July 1944, the Polish resistance (Home Army and V1 and V2) secretly transported parts of the rocket out of Poland in Operation Most III (Bridge III or Wildhorn III),[12] for analysis by British Intelligence.[8][35] The missile fragments were picked up by a RAF C-47 Dakota aeroplane from an AK agent (code name: "Motyl") in an abandoned airfield between the villages of Jadowniki Mokre and Wał-Ruda, near Żabno, at the junction of the Dunajec and Wisła rivers, Poland.[28][35]

On 13 July 1944, the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wrote a letter to Joseph Stalin,[36] informing him about the German V-2 missiles being tested in Blizna. In his letter, Churchill asked Stalin to instruct his troops, who were about 50 kilometres (31 miles) away from Dębica, to search for and preserve safely any apparatus and installations found at the base after it was captured by the advancing Soviet Army.[12][36] He also asked Stalin to allow British experts to visit Dębica to examine the missile base. Stalin granted Churchill's requests; however, at the same time he instructed his army intelligence and USSR State Defense Committee People's Commissar for Aviation Industry, Alexei Shakhurin, to get ready for the examination of the German missiles.[12] Shakhurin was ordered to have his weaponry experts in Dębica long before the British arrived.[12] In late July 1944, the advance of the Red Army forced the Germans to evacuate the base at Blizna, and launch activities were moved to the Tuchola Forest.[8][12] The Red Army reached Blizna on 6 August 1944, about ten days after the Germans had moved out. Many of the first remnants of V-2 missiles were recovered by troops of the 60th Army commanded by General Pavel Alekseyevich Kurochkin.[12] British intelligence agents were eventually granted access to the launch site in September 1944.[8] Their mission was to collect as many remaining rocket parts and as much intel on the site as they could.[8] By then, the Red Army had already cleared out most of what the Germans had left and had shipped it to the Soviet Union, following Stalin's instructions.[12] However, the British did manage to fill several crates with some useful V-2 rocket parts, which were then transported to England with the full co-operation of the Soviets.[8] When the crates were opened in London, they did not have the expected contents; instead, they contained old rusty truck and tank parts,[8] which had probably been substituted by Soviet agents.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- List of Blizna V-2 test launches

- Rocket launch site

- SS-Truppenübungsplatz Heidelager

- Operation Osoaviakhim

Annotations

[edit]- First Launch: 1943-11-05. Last Launch: 1944-07-24. Number: 277 . Location: Blizna, Poland. Longitude: 21.6162 deg. Latitude: 50.1819 deg.

- Diver – a secret British Defence Instruction specified the code name: "Enemy Flying Bombs will be referred to or known as 'Diver' aircraft or pilotless planes" to alert defences of an imminent attack (often called Operation Diver, particularly post-war, without citation).

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The modern museum is built on the exact site of the former V-2 launch site. Phase II building of the museum was completed in 2011.

- ^ The V-2 propellant formula comprises: fuel, alcohol, liquid oxygen, hydrogen peroxide and sodium permanganate (catalyst).

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Historia poligonu Heidelager" [History of Heidelager military training base] (in Polish). Republika.pl. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Artilleriezielfeld Blizna" [Blizna (treść tablicy informacyjnej na terenie dawnego poligonu).] (in German). Archived from the original on 29 March 2009.

- ^ Metz, Kaj. "SS-Truppenübungsplatz Heidelager / Concentration Camp Pustkow". TracesofWar.com. Traces of War. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Park Historyczny Blizna".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jaskólski, Paweł (3 November 2014). "Polska, Blizna – Park Historyczny Blizna" [Historical Park in Blizna, Poland]. Alemuzea.Pl (in Polish). Projekt AleMuzea!. Archived from the original on 30 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Middlebrook 1982, p. 222.

- ^ a b Jena1806.Com: 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Puszkin, Piotr (26 April 2008). "Poligon V1/V2 Blizna" [Blizna V1/V2 facility] (in Polish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Glass 2000, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Dornberger 2004, p. 18.

- ^ a b Wnuk 2012, p. 26–29 (Bogdan Chrzanowski)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zak, Anatoly: RussianSpaceWeb.Com: 2011

- ^ a b c d e f Wiąk 2003, p. 435–439.

- ^ Wnuk 2012, p. 35 (Marek Flis, Mirosław Surdej)

- ^ a b Wnuk 2012, p. 36 (Marek Flis, Mirosław Surdej)

- ^ a b c Dornberger 2004 p. 18.

- ^ Wnuk 2012, p. 36,37 (Marek Flis, Mirosław Surdej)

- ^ "Wernher von Braun : Feature Articles". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 2 May 2001. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ "Biography of Wernher Von Braun". history.msfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 11 June 2002. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ^ Gatland, Kenneth William: Project Satellite: 1958 p. 82

- ^ a b c Campbell 2012, p. 187

- ^ a b Campbell 2012, p. 188

- ^ Aldrich 2010

- ^ Glass 2000, p. 26.

- ^ a b Wnuk 2012, p. 40. (Marek Flis, Mirosław Surdej)

- ^ a b c Wnuk 2012, p. 44. (Marek Flis, Mirosław Surdej)

- ^ "Antoni Kocjan". Nekropole. 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Polish Greatness". Polish Greatness.com. 7 December 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Relacja Aleksandra Rusina, 23 IX 2007, z zbiorach Marka Flisa. (in Polish)

- ^ "A-4/V-2 Makeup – Tech Data & Markings". V2 Rocket.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ McGovern, James (1964). Crossbow and Overcast. New York: W. Morrow. p. 42.

- ^ a b c Wnuk 2012, p. 48. (Marek Flis, Mirosław Surdej)

- ^ a b c Łubieński 1976 p. 157.

- ^ a b Wojewódzki, Michał (1984). Akcja V-1, V-2 (in Polish). Warsaw. ISBN 83-211-0521-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Breuer 1993, p. 55.

- ^ a b "Correspondence between the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Presidents of the USA and the Prime Ministers of Great Britain during the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945". J. V. Stalin Archive. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aldrich, Richard James (2010). GCHQ The Uncensored Story of Britain's Most Secret Intelligence Agency (PDF). HarperPress. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Breuer, William B. (1993). Race to the Moon: America's Duel with the Soviets. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-94481-6. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Campbell, Christy (29 March 2012). Target London: Under attack from the V-weapons during WWII. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-0-7481-2201-1. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Dornberger, Walter (2004) [1952 V2–Der Schuss ins Weltall]. V-2 superbroń Trzeciej Rzeszy 1930–1945 (in Polish). Moscow: Centropoligraf.

- Gatland, Kenneth William (1958). Project Satellite. John W. Wood (First ed.). London: Wingate. p. 169. OCLC 1183846. OL 6241939M. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- Glass, A.; et al. (2000). Wywiad Armii Krajowej w walce z V-1 i V-2 [Interview of the Home Army in the Fight Against the V-1 and V-2] (in Polish). Warsaw: Mirage Hobby W-wa.

- King, Benjamin; Kutta, Timothy (15 July 2003). Impact: The History of Germany's V-Weapons in World War II. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81292-7. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- Łubieński, Konstanty (1976). Kartki z wojny / Konstanty Łubieński (in Polish). Warsaw: Ośrodek Dokumentacji i Studiów Społecznych. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Middlebrook, Martin (1982). The Peenemünde Raid: The Night of 17–18 August 1943. New York: Bobbs-Merrill. ASIN 0304353469.

- Wiąk, W (2003). Struktura organizacyjna Armii Krajowej 1939–1944 (in Polish). Warsaw. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wnuk, Rafał; Zapart, Robert; Szkudliński, Jan (2012). Blińko, Beata (ed.). Tajemnice Blizny. Wywiad Armii Krajowej w walce z rakietami V-2 [Secrets of Blizna. Polish ‘Armia Krajowa’ in the fight against V-2 rockets] (in Polish). Vol. 1 (1 ed.). Gdańsk: Muzeum II Wojny Światowej w Gdańsku oraz Fundację Armii Krajowej im. Franciszka Miszczaka w Londynie. ISBN 978-83-63709-19-8. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Wojewódzki, M (1984). Akcja V-1,V-2 (in Polish). Warsaw: PAX W-wa.

Further reading

[edit]- Dungan, Tracy D. (2005). V-2: A Combat History of the First Ballistic Missile. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 1-59416-012-0.

- Góra, Władysław (1984). Wojna i okupacja ziemiach na Polskich 1939–1945 (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Książka i Wiedza. ISBN 83-05-11290-X.

- Huzel, Dieter K. (c. 1965). Peenemünde to Canaveral. Prentice Hall Inc.

- Piszkiewicz, Dennis (1995). The Nazi Rocketeers: Dreams of Space and Crimes of War. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-95217-7.

Sources

[edit]- Cooksley, Peter G (1979). Flying Bomb. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 102, 162, 197. ISBN 0-684-16284-9.: 61

- "List of V-2 test missile launches from Blizna". jena1806.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- "Eintrag über Blizna" [Entry on Blizna] (in German). v2rakete.de. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- Zak, Anatoly. "V-2 tests in Poland". RussianSpaceWeb.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Correspondence between the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Presidents of the USA and the Prime Ministers of Great Britain during the Great Patriotic War of 1941–1945". Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin Archive. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2013.:

| PERSONAL AND MOST SECRET MESSAGE FROM MR CHURCHILL TO MARSHAL STALIN

13 July 1944 1. There is firm evidence that the Germans have been conducting the trials of flying rockets from an experimental station at Dębice in Poland for a considerable time. According to our information this missile has an explosive charge of about twelve thousand pounds and the effectiveness of our counter-measures largely depends on how much we can find out about this weapon before it is launched against this country. Dębice is in the path of your victorious advancing armies and it may well be that you will overrun this place in the next few weeks. 2. Although the Germans will almost certainly destroy or remove as much of the equipment at Dębice as they can, it is probable that a considerable amount of information will become available when the area is in Russian hands. In particular we hope to learn how the rocket is discharged as this will enable us to locate the launching sites. 3. I should be grateful, therefore, Marshal Stalin, if you could give appropriate instructions for the preservation of such apparatus and installations at Dębice as your armies are able to ensure after the area has been overrun, and that thereafter you would afford us facilities for the examination of this experimental station by our experts. – Winston Churchill |

|---|

Gallery

[edit]-

V-2 rocket in Blizna, 1943

-

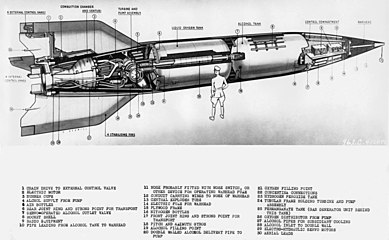

Layout of a V-2 rocket

-

Replica V-2 missile in Blizna V-2 War Museum

-

A V-2 missile being launched in summer 1943

-

Post-war 1946 Russian Antonov An-2 aeroplane at Blizna V-2 Museum

-

V-2 missile fragments Blizna V-2 War Museum

External links

[edit]- Park Historyczny Blizna live cam

- BLIZNA – Poligon rakietowy V-1 V-2 (in Polish) Video on YouTube

- Instagram photos

- Archived Truppenubungsplatz Heidelager. German test range for production V-2 missiles.

- Zdjęcia Parku Historycznego BLIZNA