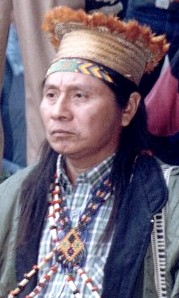

Berito Kuwaru'wa

Berito Kuwaru'wa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Barranquilla, Colombia |

| Nationality | Colombian |

| Known for | Spokesman for the U'wa people |

| Awards | Goldman Environmental Prize (1998) |

Berito Kuwaru'wa is a member of the Colombian U'wa people. He was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 1998[1] for his role as spokesperson in conflicts between the U'wa people and the petroleum industry.

Early life

[edit]In 1963, when he was a small child, Kuwaru’wa was kidnapped by Catholic missionaries to live at a mission and be indoctrinated into Western culture. He was given the name Roberto Cobraría and taught to read and write Spanish, until several years later where his mother managed to rescue him. Distressed by the experience and impassioned by the missionaries’ disregard for his people’s culture, Kuwaru’wa cites his time living in a mission as what began his campaign to fight for U’wa rights.[2][3]

Occidental Petroleum

[edit]In 1992, Occidental Petroleum, or Oxy, an American hydrocarbon exploration company, received a license from the Colombian government to search for oil in U’wa territory,[2][4] violating a 1991 ruling by the International Labor Convention that asserts that community consent must exist for resource exploitation to occur on their territory.[5]

In response, Kuwaru’wa and the U’wa people publicly and internationally expressed their opposition towards all oil operations.[1] In 1995, Kuwaru’wa led a legal challenge to the Colombian Supreme Court, persuading them to overturn the decision to allow Oxy to explore U’wa territories for oil, declaring a suicide pact.[4][6][7]

Kuwaru’wa would also take the campaign to the Inter-American Commission in 1997 to argue that Oxy’s exploration of U’wa land violated their rights to a clean environment and living conditions.[4][8]

Kuwaru’wa travelled to the United States in 1996, to demonstrate to Occidental executives through song that the traditional territory of the U’wa would not be ceded. This song related the U’wa creation mythology and sacred beliefs to petroleum, and how the U’wa consider petroleum extraction to be sacrilege.[1][4][9] Kuwaru’wa travelled internationally, gathering attention and support for his cause worldwide.

In 1997, Kuwaru’wa was attacked by hooded men, who threatened him with death to force him to sign an oil drilling authorization agreement. When he refused, he was beaten and pushed into a river, where he nearly drowned. The Organization of American States (OAS) subsequently ordered the Colombian government to protect Kuwaru’wa.[1]

Occidental Petroleum announced the end of their petroleum operations on U’wa territory in 1998, and withdrew from U’wa land in 2002.

EcoPetrol

[edit]To preemptively prevent U’wa territory to be exploited for oil, Kuwaru’wa used the funds he obtained from the Goldman Environmental Prize to purchase plots of land in a community known as La China, a place where he believed Oxy would explore next. Even though the purchased land was not the large source of oil that was anticipated to be drilled, the plot would prove to be an important asset for future U’wa resistance against another petroleum company known as Ecopetrol.[6]

In 2014, Ecopetrol, a Colombian petroleum refinery company, came to the Magallanes oil block to extract oil, located just outside the government-recognized U’wa reservation. In the same year, a section of Ecopetrol’s Caño Limón pipeline located in La China was illegally bombed by an unrelated party, the National Liberation Army,[10][11] resulting in additional pollution in the surrounding area.[12]

Exercising their legal rights of ownership of La China, the U'wa people occupied the damaged pipeline site, refusing to permit any repairs on the pipelines until the Colombian government addressed their demands to prohibit oil excavation companies to enter their territory.[10][13] In an effort to dissuade the Colombian government from forcibly removing them from their land, Kuwaru’wa reached out to their international partners to raise awareness and push for a peaceful resolution with the government.[10][13]

Activism and beliefs

[edit]As a spokesperson, Kuwaru’wa expressed the U’wa belief that God intended for the U’wa to protect the natural environment and that humanity’s survival depends on the health of the earth. To the U’wa people, oil is the earth’s blood, and to harvest it would be attacking earth and all of humanity.[2][3]

Kuwaru’wa asserted that the U’wa people would rather die protecting their cultural and religious values than allow petroleum companies to take from their land, a sentiment that would resonate with international conservationist activists.[14][15]

Kuwaru’wa urges petroleum companies and other stakeholders to reflect on the future impacts of oil drilling and other related industries. He warns of uncontrollable consequences such as irregular weather patterns, earthquakes, and hurricanes as a result of the earth’s disturbed equilibrium.[12][13]

Awards and recognition

[edit]In 1998, Berito Kuwaru’wa was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for his work as a spokesperson for the U’wa people, internationally spreading his culture’s conservationist message.. Additionally, he was awarded the Spanish Government’s Bartolome de las Casas Award, an award that recognizes leadership roles in protecting rights and values of indigenous people, at an unknown date.[16][17]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Goldman Environmental Prize: Berito Kuwaru'wa Archived 2007-12-04 at the Wayback Machine (Retrieved on November 28, 2007)

- ^ a b c "Berito Kuwaru'wa: 1998 Goldman Prize winner, Colombia". Youtube. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Voices of Amerikua I Berito Kuwaruwa (Cobaría), Pueblo U'Wa - Colombia". Youtube. 13 July 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Victoria (2020). Indigenous peoples: an encyclopedia of culture, history, and threats to survival. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, an Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC. pp. 1102–1103. ISBN 978-1-4408-6118-5.

- ^ "C169 - Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169)". International Labour Organization. 27 June 1989. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Berito's Vision | Amazon Watch". 2017-02-18. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Arellano Martinez, Juan Martin (2012). "Indigenous Peoples' Struggle for Autonomy: The Case of the U'wa People" (PDF). Paterson Review of International Affairs. 12: 109–122 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Report No. 33/15 Case 11.754" (PDF). Organization of American States. 22 July 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Werjayo Berito Kuwaru'wa and the Seeds Alliance in the UK". Inti & Waira Shop. 2020-08-22. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ a b "Colombia's U'Wa People Refuse to Permit Repairs on Broken Oil Pipeline until the Government Addresses their Demands". Goldman Environmental Prize. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ Bedoya, Nicolas (2014-06-02). "Northeast Colombia indigenous say government broke deal allowing oil pipeline repair". Colombia News | Colombia Reports. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ a b "A Message from the U'wa of Colombia". Youtube. 20 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Propuestas de la nación U'wa al gobierno colombiano" (PDF). Amazon Watch. 25 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "The Right to Decide: U'wa Bring Case to Court After 25 Years | Amazon Watch". 2023-04-20. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ "OCCIDENTAL PETROLEUM OFF U'WA LANDS". Earth First!. 19 (6). 31 July 1999. ProQuest 221820345 – via Proquest.

- ^ Pate II, William O. (2000-07-07). "U'wa in Crisis: Chronology 1988-2000". San Antonio Review.

- ^ Soltani, Atossa; Koenig, Kevin. "U'wa Overcome Oxy: How a Small Ecuadorian Indigenous Group and Global Solidarity Movement Defeated An Oil Giant, and the Struggles Ahead". Multinational Monitor. 25 (1–2): 9–12. ProQuest 208868317 – via ProQuest.