Bartol Kašić

Bartol Kašić | |

|---|---|

Kašić bust in the Town of Pag | |

| Born | August 15, 1575 |

| Died | December 28, 1650 (aged 75) Rome |

| Other names | Bartul Kašić Bogdančić (signature) Pažanin ("of Pag", signature) |

| Citizenship | Republic of Ragusa, Republic of Venice |

| Education | Illyric College in Loreto Rome |

Bartol Kašić (Croatian pronunciation: [bâːrtol kǎʃit͡ɕ]; Latin: Bartholomaeus Cassius, Italian: Bartolomeo Cassio; August 15, 1575 – December 28, 1650) was a Croatian Jesuit clergyman and grammarian during the Counter-Reformation, who wrote the first Illyrian grammar and translated the Bible and the Roman Rite[clarification needed] into Illyrian (a name used for the early Croatian or Serbo-Croatian language).

Life

[edit]Bartol was born in Pag, in the Republic of Venice (in modern Croatia) of his father Ivan Petar Kašić who participated in the 1571 Battle of Lepanto and mother Ivanica.[1] In 1574 Ivan Petar Kašić married for Ivanica Bogdančić and they had a son Bartol next year.[1] His father died when he was a small child, so he was raised by his uncle Luka Deodati Bogdančić, a priest from Pag, who taught him to read and write. He attended the municipal school in the town of Pag. After 1590 he studied at the Illyric College in Loreto near Ancona, in the Papal States (in modern Italy), managed by the Jesuits. As a gifted and industrious pupil, he was sent to further studies in Rome in 1593, where he joined the Society of Jesus in 1595. Kašić continued propaganda activities of Aleksandar Komulović after his death, being even greater Pan-Slav then Komulović was.[2] Kašić censored and edited Komulović's 1606 work (Zrcalo od Ispovijesti).[3]

Kašić was made a priest in 1606 and served as a confessor in the St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. He lived in Dubrovnik from 1609 to 1612. In 1612/13, disguised as a merchant, he went on a mission to the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia, central Serbia and eastern Slavonia (Valpovo, Osijek, Vukovar), which he reported to the pope. From 1614 to 1618 he was the Croatian confessor in Loreto. He went on his second mission in 1618/19. In old age, he described both missions in his incomplete autobiography. His second stay in Dubrovnik lasted from 1620 to 1633. Then he returned to Rome, where he spent the rest of his life.

Literary activity

[edit]Already as a student, Kašić started teaching Illyrian in the Illyric Academy in Rome, which awakened his interest in Illyrian. By 1599, he made a Illyrian-Italian dictionary, one of the first Croatian dictionaries, which has been preserved as a manuscript in Dubrovnik since the 18th century. Some experts[who?] believe it is one of three dictionaries made by Kašić and that the other two are archived in Perugia and Oxford.[citation needed]

Kašić's native dialect was Chakavian.[4] In the 16th century, the Chakavian dialect was prevalent in Croatian works, though it now shifted towards the Shtokavian.[5] Kašić opted for Shtokavian as it was the most common dialect among his South Slavic (Illyrian) people.[6]

The first Illyrian grammar

[edit]

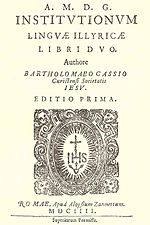

It qualified Kašić for further work in Illyrian. Since the Jesuits took care of the Christians in the Ottoman Empire and tried to teach in the local language, they needed an adequate textbook for working among the Croats. In 1582, Marin Temperica wrote a report to general Claudio Acquaviva in which he emphasized the importance of the Slavic language understandable all over the Balkans.[7] In this report of Temperica requested publishing of the Illyrian language dictionaries and grammars.[8] Based on this request, Kašić provided such a textbook; he published Institutionum linguae illyricae libri duo ("The Structure of the Illyrian Language in Two Books") in Rome in 1604. It was the first Slavic language grammar.[9]

In under 200 pages and two parts ("books"), he provided basic information on Illyrian and explained the Illyrian morphology in great detail. The language is basically Shtokavian with many Chakavian elements, mixing older and newer forms. For unknown reasons, the grammar was not accompanied by a dictionary, as was the practice with Jesuit dictionaries and grammars of Illyrian.

In 1612–1613 and then again in 1618–1620, Kašić visited various regions of Ottoman Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia.[10] After 1613 Kašić published several works of religious and instructive content and purpose (the lives of the saints Ignatius of Loyola and Francis Xavier, the lives of Jesus and Mary), a hagiographic collection Perivoj od djevstva (Virginal Garden; 1625 and 1628), two catechisms, and so on. In late 1627, he completed the spiritual tragedy St. Venefrida, subtitled triomfo od čistoće (a triumph of purity), which remained in manuscript until 1938.[clarification needed][citation needed]

Translation of the Bible

[edit]In 1622, Kašić started translating the New Testament into the local Slavic vernacular – more precisely, the Shtokavian dialect of Dubrovnik. In 1625, he was in charge of translating the entire Bible. He submitted the entire translation in Rome in 1633 to obtain the approval for printing, but he encountered difficulties because some Croatians were against translations in that vernacular.[citation needed]

Considering the fact that the translations of the Bible to local languages had a crucial role in the creation of the standard languages of many peoples, the ban on Kašić's translation has been described by Josip Lisac as "the greatest catastrophe in the history of Croatian".[11] The preserved manuscripts were used to publish the translation, with detailed expert notes, in 2000.

The great linguistic variety and invention of his translation can be seen from the comparison with the King James Version of the Bible. The King James Version, which has had a profound impact on English, was published in 1611, two decades before Kašić's translation. It has 12,143 different words. Kašić's Croatian translation, even incomplete (some parts of the Old Testament are missing), has around 20,000 different words – more than the English version and even more than the original Bible!

Roman Rite

[edit]

Ritual rimski ("Roman Rite", 1640),[clarification needed] covering more than 400 pages, was the most famous Kašić's work, which was used by all Croatian dioceses and archdioceses except for the one in Zagreb, which also accepted it in the 19th century.

Kašić called the language used in Ritual rimski as naški ("our language") or bosanski ("Bosnian"). He used the term "Bosnian" even though he was born in a Chakavian region: instead he decided to adopt a "common language" (lingua communis), a version of Shtokavian Ikavian, spoken by the majority the speakers of Serbo-Croatian. He used the terms dubrovački ("Dubrovnikan") for the Ijekavian version used in his Bible, and dalmatinski (Dalmatian) for the Chakavian version.

Works

[edit]- Razlika skladanja slovinska (Croatian-Italian dictionary), Rome, 1599

- Institutionum linguae illyricae libri duo (The Structure of the Illyrian (Croatian) Language in Two Books), Rome, 1604

- Various hagiographies; collection Perivoj od djevstva (Virginal Garden; 1625 and 1628) *Two catechisms

- Spiritual tragedy St Venefrida, 1627, published in 1938

- The Bible, 1633

- Ritual rimski (Roman Rite), 1640

References

[edit]- ^ a b "tzgpag"

- ^ Zlatar, Zdenko (1992). Between the Double Eagle and the Crescent: The Republic of Dubrovnik and the Origins of the Eastern Question. East European Monographs. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-88033-245-3.

After his death his propaganda activities were continued by an even greater Pan-Slav: Bartol Kasic.

- ^ Church, Catholic; Kašić, Bartol; Horvat, Vladimir (1640). Ritval Rimski: po Bartolomeu Kassichiu od Druxbae Yesusovae. Kršćanska sadašnjost. p. 457.

Ujedno je 1606. bio cenzor i redaktor djela Aleksandra Komulovića Zarcalo od ispovijesti, koje je objavljeno u Rimu 1606. i(li) 1616, pa opet u Veneciji 1634.

- ^ Harris, Robin (January 2006). Dubrovnik: A History. Saqi Books. p. 236. ISBN 9780863569593.

Kasic hailed from the Dalmatian island of Pag and so, like Komulovic, he spoke the Croatian variant known as cakavski (or cakavian).

- ^ Črnja, Zvane (1962). Cultural History of Croatia. p. 280.

- ^ Sugar, Peter F (1977). Southeastern Europe Under Ottoman Rule, 1354-1804. University of Washington Press. p. 260. ISBN 9780295803630.

- ^ Franičević, Marin (1986). Izabrana djela: Povijest hrvatske renesansne književnosti. Nakladni zavod Matice hrvatske. p. 190.

Osnivanje Ilirskih zavoda u Loretu i Rimu, spomenica koju će Marin Temperica, pošto je stupio u isusovački red, uputiti generalu reda Aquavivi, o potrebi jedinstvenoga slavenskog jezika koji bi mogli razumjeti »po cijelom Balkanu« (1582), ...

- ^ Franičević, Marin (1974). Pjesnici i stoljeća. Mladost. p. 252.

Tako se dogodilo da je isusovac Marin Temperica već u XVI stoljeću pisao spomenicu o potrebi zajedničkog jezika, tražeći da se napiše rječnik i gramatika.

- ^ Istoricheski pregled. Bŭlgarsko istorichesko druzhestvo. 1992. p. 9.

... езуит Марин Темперица предава на генерала на езуитите в Рим, Клаудио Аквавива, предложение за възприемане на един език за славяните на Балканите. Плод на това искане е първата славянска граматика

- ^ O'Neill, Charles E.; Domínguez, Joaquín María (2001). Diccionario histórico de la Compañía de Jesús: Infante de Santiago-Piatkiewicz. Univ Pontifica Comillas. p. 2899. ISBN 978-84-8468-039-0.

- ^ "Neizdavanje Kašićeve Biblije najveća katastrofa hrvatskoga jezika" (in Croatian). Zadarski list. 31 March 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

Sources

[edit]In Croatian:

- Hrvatska biblija Bartola Kašića (Croatian Bible of Bartol Kašić), Slobodna Dalmacija, December 5, 2000

- Zaslužni jezikoslovac Bartol Kašić (Bartol Kašić, the Great Linguist), Vjesnik, May 28, 1999[permanent dead link]

- Bartol Kašić

- Bartol Kašić i Biblija

- 1575 births

- 1650 deaths

- 16th-century Croatian Roman Catholic priests

- 17th-century Croatian Roman Catholic priests

- 16th-century Croatian Jesuits

- 17th-century Croatian Jesuits

- 17th-century Venetian writers

- Ragusan clergy

- Linguists from Croatia

- Croatian lexicographers

- Croatian Jesuits

- Translators of the Bible into Croatian

- History of the Serbo-Croatian language

- Republic of Venice clergy

- Venetian Slavs

- Ragusan Jesuits

- Venetian Jesuits

- 17th-century Italian Jesuits

- Roman Catholic missionaries in Croatia

- Missionary linguists

- Italian–Croatian translators

- 17th-century Croatian writers

- 17th-century male writers

- 17th-century Jesuits

- 16th-century Jesuits

- Roman Catholic biblical scholars