Atsuta Shrine

| Atsuta Shrine 熱田神宮 | |

|---|---|

The haiden, or prayer hall, 2019 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Shinto |

| Deity | Atsuta no Ōkami Amaterasu Susanoo Yamatotakeru Miyazu-hime Takeinadane |

| Festival | Atsuta-sai; June 5th |

| Type | Chokusaisha Beppyo jinja, Shikinaisya Owari no Kuni sannomiya (Former kanpeitaisha) |

| Location | |

| Location | 1-1-1, Jingu, Atsuta-ku Nagoya, Aichi 456-8585 |

| Geographic coordinates | 35°07′39″N 136°54′30″E / 35.12750°N 136.90833°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Shinmei-zukuri |

| Website | |

| www | |

Atsuta Shrine (熱田神宮, Atsuta-jingū) is a Shinto shrine, home to the sacred sword Kusanagi no Tsurugi, one of the three Imperial Regalia of Japan—traditionally believed to have been established during the reign of Emperor Keikō (reigned 71–130 CE). It is located in Atsuta-ku, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture in Japan.[1] The shrine is familiarly known as Atsuta-Sama (Venerable Atsuta) or simply as Miya (the Shrine). Since ancient times, it has been especially revered, ranking with the Ise Shrine.[2]

The 200,000-square-metre (2,200,000 sq ft) shrine complex draws over 9 million visitors annually.[2]

History

[edit]

The Kojiki explains that Atsuta Shrine was founded to house the Kusanagi no Tsurugi, a legendary sword.

According to traditional sources, Yamato Takeru died in the 43rd year of Emperor Keiko's reign (景行天皇43年, equivalent 113 AD).[3] The possessions of the dead prince were gathered together along with the sword Kusanagi; and his widow venerated his memory in a shrine at her home. Sometime later, these relics and the sacred sword were moved to the current location of the Atsuta Shrine.[4] Nihonshoki explains that this move occurred in the 51st year of Keiko's reign, but shrine tradition also dates this event in the 1st year of Emperor Chūai's reign.[5]

The Owari clan had established the Atsuta Shrine in 192, and held the position of the shrine's high priest since ancient times, passing it down from generation to generation. However, in 1114, Kazumoto handed the position over to Fujiwara no Suenori, who was from the Fujiwara clan.[6] Since then, the Fujiwara clan became the head of Atsuta Shrine, while the Owari clan stepped down to the position of adjutant chief priest (gongūji).[7]

During the Northern and Southern Courts Period, because it was believed that the Kusanagi no Tsurugi was or had once been housed there, the Atsuta Shrine proved to be a significant site in the struggle between ousted Emperor Go-Daigo (Southern Court) and the new emperor, Takauji Ashikaga (Northern Court). Go-Daigo was a patron to Atsuta Masayoshi, the shrine's attendant, who subsequently fled with him to Mt. Hiei in 1336 and went on to command troops on Go-Daigo's behalf in 1337. In 1335, after rebelling against Go-Daigo, Takauji appointed a new shrine attendant. He later prayed there while advancing on the capital, mimicking the behavior of Minamoto no Yoritomo, who had done the same before founding the Kamakura shogunate.[8]

In 1338, the Southern Court had one more chance to occupy the shrine when Kitabatake Akiie led a large army down from the Southern Court's base on Mount Ryōzen.[8][9] In the first month of 1338, Akiie also prayed at the shrine. However, he was killed in battle soon after and the Ashikaga cemented their control over Atsuta Shrine.[8]

From 1872 through 1946, Atsuta Shrine was officially designated one of the Kanpei-taisha (官幣大社), meaning that it stood in the first rank of government supported shrines.[10]

The shrine area was originally much larger. To the northeast were vast ricefields that belonged to the shrine, they were later built over in what became Sanbonmatsu-chō (三本松町) and Mutsuno (六野) neighbourhoods, the Jingū Higashi Park (神宮東公園) established in the 1980's is a restoration of greenery to the site.[11][12]

Architecture

[edit]

The shrine's buildings were maintained by donations from a number of benefactors, including well-known Sengoku period figures like Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and the Tokugawas. For example, the Nobunaga-Bei, a 7.4 m high roofed mud wall, was donated to the shrine in 1560 by Nobunaga as a token of gratitude for his victory at the Battle of Okehazama.[13] A wooden gate called Kaijō-mon (海上門 lit. "Sea Gate") was made along with the mud wall. This gate was a National Treasure and was lost during the Pacific war bombings on 17 May 1945.[14][15] The west gate was a larger wooden structure called Chinkō-mon (鎮皇門) that was used for imperial processions.[16] It was dedicated by Kato Kiyomasa. This gate was also registered as a national treasure, it was lost 29 July 1945 in another air raid.[17][18] and replaced with a simple wooden torii. The east gate Shunkō-mon (春敲門) was dedicated to Yang Guifei, who according to legend found refuge here. A water spring is also connected to her legend.[19][20]

In 1893, it was remodeled using the Shinmeizukuri architectural style, the same style used in the building of Ise Shrine. Before a celebration in 1935, the shrine's buildings as well as other facilities were completely rearranged and improved in order to better reflect the history and cultural significance of the shrine.[2]

During the aerial raids of the Pacific War, however, many of Atsuta Shrine's buildings were destroyed by fire. The shrine's main buildings, such as the honden, were reconstructed and completed in 1955.[2] Following the completion of these buildings, construction of other buildings continued on the shrine grounds. In 1966 the Treasure Hall was completed in order to house the shrine's collection of objects, manuscripts and documents.[21]

Augmented reality was developed to see structures that have been lost over time.[22]

Shinto belief

[edit]This Shinto shrine is dedicated to the veneration of Atsuta-no-Ōkami. Also enshrined are the "Five Great Gods of Atsuta", all of whom are connected with the legendary narratives of the sacred sword — Amaterasu-Ōmikami, Takehaya Susanoo-no-mikoto, Yamato Takeru-no-mikoto, Miyazu-hime, and Take Inadane-no-mikoto.[23]

Atsuta is the traditional repository of Kusanagi no Tsurugi, the ancient sword that is considered one of the Three Sacred Treasures of Japan.[24] Central to the Shinto significance of Atsuta Shrine is the sacred sword which is understood to be a gift from Amaterasu Ōmikami. This unique object has represented the authority and stature of Japan's emperors since time immemorial. Kusanagi is imbued with Amaterasu's spirit.[25]

During the reign of Emperor Sujin, duplicate copies of the Imperial regalia were made in order to safeguard the originals from theft.[26] This fear of theft proved to be justified during the reign of Emperor Tenji when the sacred sword was stolen from Atsuta; and it was not to be returned until the reign of Emperor Tenmu.[3] There is also the purported loss of the Kusanagi during the 1185 Battle of Dan-no-ura, where it was presumed lost at sea when the Emperor Antoku committed suicide by drowning together with remnants of the Heike. Although not seen by the general public since that time, it is said to have remained in safekeeping at the shrine up to the present day.

Treasures

[edit]

The shrine's Bunkaden, or treasure hall, houses over 4,000 relics, which include 174 Important Cultural Properties and a dagger that is a designated National Treasure of Japan. Atsuta Jingu Museum preserves and displays a variety of historic material, including the koshinpō (sacred garments, furniture and utensils for use of the enshrined deities). A number of donated swords,[27] mirrors and other objects are held by the shrine, including Bugaku masks and other material associated with ancient court dances. The Bunkaden collection ranges from ancient documents to household articles. Aichi Prefecture has designated 174 items as important cultural assets.[28]

Festivals

[edit]

Over 70 ceremonies and festivals are held annually at the shrine.[21]

- Hatsu-Ebisu (January 5): Seeking good fortune in the new year from Ebisu, the kami of Fortune.[30]

- Yodameshi Shinji (January 7): The projected annual rainfall for the coming year is prophesied by measuring the amount of water in a pot kept underneath the floor of the Eastern Treasure House.[30]

- Touka Shinji (January 11): A variation on an annual ceremony (Touka-no-sechie) of the Imperial Court in the Heian period (10th-12th Century), the shrine dance becomes a prayer in movement hoping for bumper crops of the year.[30]

- Hosha Shinji (January 15): Ceremonial which involves shooting an arrow at a wooden piece called chigi fixed at the center of a huge mark.[30]

- Bugaku Shinji (May 1): A ceremonial dance from the Heian era is performed outdoors on a red painted stage.[30]

- Eyoudo Shinji (May 4): A festival to commemorate the return of the sacred sword in the reign of Emperor Tenji.[30]

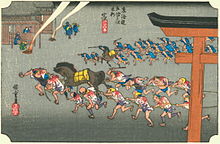

- Shinyo to Gyoshinji 神輿渡御神事 (lit. "Mikoshi passing ritual") (May 5): A festival in which portable shrine (mikoshi) is carried in a formal procession to the western gate Chinkō-mon, where ceremonies and prayers for the security of the Imperial Palace are performed in the open air.[31][30][32] In the Meiji and Taishō era, this procession moved in sober and solemn silence. The ceremony at the gate was brief, lasting only 20 minutes; and then the mikoshi and its attendants returned into the Shrine precincts. Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa provided a new mikoshi and a complete set of robes and other accouterments for this festival on the occasion of repairs to the shrine in the 1457-1459 (Chōroku 1-3).[33]

- Rei Sai (June 5): Portable tabernacles (mikoshi) in various styles are carried along the approaches to the shrine; and at night, groups of 365 lanterns (makiwara) appear lit at the gates.[30] This festival commemorates an Imperial proclamation (semmyō) issued in 1872 (Meiji 5). After 1906 (Meiji 39), exhibitions of judo, fencing (gekken), and archery (kyūdō) are presented for the gratification of the kami.[33]

Auxiliary shrines

[edit]The Atsuta Shrine has 1 betsugū, 8 sessha, and 19 massha inside the hongū, and 4 sessha and 12 massha outside hongū, 45 shrines in total (including the hongū).[34]

Betsugū

[edit]Sessha

[edit]- Ichinomisaki Shrine

- Hisakimiko Shrine

- Hikowakamiko Shrine

- Minamishingūsha

- Mita Shrine

- Shimochikama Shrine

- Kamichikama Shrine

- Ryū Shrine

Sessha outside hongū

[edit]- Takakuramusubimiko Shrine

- Hikamianego Shrine

- Aofusuma Shrine

- Matsugo Shrine

Massha

[edit]- Yako-no-Yashira

- Tōsu-no-Yashira

- Reinomimae-sha

- others

Gallery

[edit]-

Postcard of the east gate Shunkō-mon (春敲門) dedicated to Yang Guifei.[36] The gate was a National Treasure and was lost in the Pacific War.

-

Main torii

-

Kusanagi Square

Access

[edit]The subway stations Atsuta Jingu Temma-cho Station and Atsuta Jingu Nishi Station serve the area. Atsuta Station is a JR station. Jingū-mae Station is a Meitetsu station.

See also

[edit]- List of Shinto shrines

- List of Jingū

- Yaizu Shrine

- List of National Treasures of Japan (crafts-swords)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1962). Studies in Shinto and Shrines. pp. 429-453. ISBN 9780710310590

- ^ a b c d Atsuta-jingū org: Archived June 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine "Introduction." Archived April 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Ponsonby-Fane, p. 433.

- ^ Ponsonby-Fane, p. 434.

- ^ Ponsonby-Fane, p. 435.

- ^ Naito, Toho (1975). Choshu Zasshi (張州雑志). Aichi-ken Kyōdo Shiryō Kankō-kai. doi:10.11501/9537297.

- ^ Ota, Akira (1942). Seishi Kakei Daijiten (姓氏家系大辞典). Vol. 1. Kokuminsha. pp. 1038–1051. OCLC 21114789.

- ^ a b c Conlan, Thomas Donald (2011-08-11). From Sovereign to Symbol: An Age of Ritual Determinism in Fourteenth Century Japan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199778119.

- ^ ""Ryouzen Ima Mukashi Monogatari" Tourism Pamphlet" (PDF). date-shi.jp. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Shinto: Atsuta Shinkō

- ^ "Nic Walking Guides: Miya to Atsuta" (PDF). www.nic-nagoya.or.jp.

- ^ "Jinguhigasi" (PDF). www.city.nagoya.jp.

- ^ Atsuta-jingū org: "Precinct" (map). Archived April 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "大正時代の名古屋「熱田神宮 信長塀と海上門(国宝)」 : Network2010.org". コンテンツ投稿. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ a b haru_tsuji. "熱田神宮にあった国宝の門/海上門". 緑区周辺そぞろ歩き (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "『【 熱田神宮鎮皇門(あつたじんぐう ちんこうもん)】』". 八百万の神の浮世絵師 持田大輔 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "昭和初期の名古屋「熱田神宮鎮皇(ちんこう)門」 : Network2010.org". コンテンツ投稿. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "今昔写語". [愛知県]熱田神宮鎮皇門の古写真 | 昔の写真のあの場所は今どうなっている?昔と今を比較する写真ギャラリー「今昔写語」 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "<あいちの民話を訪ねて>(12)楊貴妃伝説(名古屋市熱田区):中日新聞Web". 中日新聞Web (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ shirotoshiseki (2021-10-16). "熱田神宮に楊貴妃の墓があった!清水社の場所と行き方を地図で説明". ゼロからはじめる愛知の城跡と御朱印、戦国史跡巡り講座 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ a b Organization, Japan National Tourism. "Atsuta-jingu Shrine | Travel Japan - Japan National Tourism Organization (Official Site)". Travel Japan. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "名古屋市:AR・VR技術を活用した、熱田区の歴史体感事業「熱田歴史探訪」が始まりました!(熱田区)". www.city.nagoya.jp. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ Ponsonby-Fane, p. 429.

- ^ JapanGuide.com: Atsuta Shrine

- ^ Ponsonby-Fane, pp. 438-439.

- ^ Ponsonby-Fane, pp. 430-431.

- ^ Sato, Yuji (29 November 2021). "Nagoya's Atsuta Jingu shrine puts its monster-size swords on show". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ "Treasure | ATSUTA JINGU". www.atsutajingu.or.jp. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "Festival of the Atsuta Shrine at Miya, no. 42 from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō". allenartcollection.oberlin.edu. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Festivals". Atsuta-jingū org. June 15, 2024.

- ^ "神輿渡御神事 | 催事・神事|熱田神宮 | 初えびす 七五三 お宮参り お祓い 名古屋". www.atsutajingu.or.jp. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "shin'yo togyo shinji". kikuko-nagoya.com. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ a b Ponsonby-Fane, p. 452.

- ^ "別宮・摂社・末社(熱田神宮公式サイト)" [Betsugu・Sessha・Massha (Atsuta Shrine official website)]. www.atsutajingu.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ^ "戦災で焼失した熱田神宮の海上門を、ARで復元。「調査のプロ」が明らかにした歴史の事実とは?|ナカシャクリエイテブ 文化情報部". note(ノート) (in Japanese). 2023-08-28. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "<あいちの民話を訪ねて>(12)楊貴妃伝説(名古屋市熱田区):中日新聞Web". 中日新聞Web (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-10-27.

References

[edit]- Iwao, Seiichi, Teizō Iyanaga, Susumu Ishii and Shôichirô Yoshida. (2002). Dictionnaire historique du Japon. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose. ISBN 978-2-7068-1575-1; OCLC 51096469

- Ponsonby-Fane, Richard Arthur Brabazon. (1962). Studies in Shinto and Shrines. Kyoto: Ponsonby Memorial Society. OCLC 3994492

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Atsuta Shrine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Atsuta Shrine at Wikimedia Commons

- (in Japanese) Atsuta-jingū website

- (in English) Atsuta-jingū website

- Beppyo shrines

- Jingū

- Shinto shrines in Nagoya

- National Treasures of Japan

- Important Cultural Properties of Japan

- Buildings and structures in Japan destroyed during World War II

- Yayoi period

- Religious buildings and structures completed in 1955

- Kanpei Taisha

- Myōjin Taisha

- Chokusaisha

- Atsuta Shrine

- Aichi Prefecture designated tangible cultural property

- Owari clan

- Yamato Takeru Legend

- Kusanagi no Tsurugi

- Shinmei-zukuri

![Postcard of the Kaijō-mon (海上門 lit. "Sea Gate") with the earthen Nobunaga-bei wall that remains. The gate was a National Treasure and was lost in the Pacific War. It can be seen through augmented reality.[35][15]](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Postcard_of_Gate_Kaijo-Mon_Atsuta_Shrine_Scan10007.jpg/120px-Postcard_of_Gate_Kaijo-Mon_Atsuta_Shrine_Scan10007.jpg)

![Postcard of the east gate Shunkō-mon (春敲門) dedicated to Yang Guifei.[36] The gate was a National Treasure and was lost in the Pacific War.](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e0/Postcard_of_gates_of_Atsuta_Shrine_02.jpg/120px-Postcard_of_gates_of_Atsuta_Shrine_02.jpg)