Arakkal kingdom

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Arakkal Kingdom | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1545–1819 | |||||||||

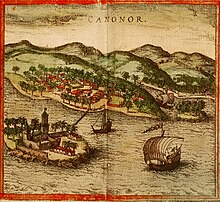

| Capital | Cannanore, Konni (now Kannur) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Malayalam | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1545 | ||||||||

• Annexed to British India | 1819 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Arakkal Kingdom (Malayalam: [ɐrɐjkːɐl]) was a Muslim kingdom in Kannur town in Kannur district, in the state of Kerala, South India. The king was called Ali Raja and the ruling queen was called Arakkal Beevi.[1] Arakkal kingdom included little more than the Cannanore town and the southern Laccadive Islands (Agatti, Kavaratti, Androth and Kalpeni, as well as Minicoy), originally leased from the Kolattiri. They owed allegiance to the Kolattiri rulers, whose ministers they had been at one time. The rulers followed the Marumakkathayam system of matrilineal inheritance, a system that is unique to a section of Hindus of Kerala. Under Marumakkathayam, the succession passes to the male offspring of its female members, in other words from a man to his sister's son and so forth. As the only Muslim rulers in Malabar, they saw the rise of Hyder Ali, de facto ruler of the Mysore Sultanate as the opportunity to increase their own power at the expense of Chirakkal, and invited him to invade Kerala.

The Bibi received no special treatment after the treaties of Srirangapatam, and settlement negotiations were long and difficult but she finally signed an agreement in 1796 that guaranteed continued possession of the city of Cannanore and the Laccadive Islands but deprived her of any claim to sovereignty. Yet, as late as 1864, the Bibi of Cannanore was included in an official list of "native sovereigns and chiefs" as being entitled to a seven-gun salute. Because of the outbreak of the war with France shortly after the 1796 agreement, as well as other considerations, the Laccadive Islands remained unnoticed and the Bibi continued to rule them with no restrictions. The islands were misgoverned throughout the 19th century, and the British Government had to assume their administration at least twice, from 1854 to 1861, and again (permanently as it turned out) in 1875. In 1905, in exchange for the remission of overdue tribute, the payment of an annual pension to the head of the family, and the title of Sultan, the Ali Raja at last agreed to cede all rights, whether as sovereign or tenant, to the Laccadive Islands, including Minicoy, which the family claimed as their private property.

The king's palace, which he purchased from the Dutch in 1663, was named Arakkal Palace after the ruling dynasty.

Origins

[edit]

As per legend, the last ruler of the Chera Empire, Rama Varma Kulashekhara Perumal, is said to have been converted to Islam at the hands of Malik Bin Dinar,[2] an Islamic missionary. Perumal along with Malik Deenar came from Mahodyapuram (Old name of Kodungallur -The capital of the Chera Empire) to Thalassery, to visit Perumal's sister and nephew residing there. Perumal's sister Sridevi and nephew Mabeli were residing in a place called Dharmadam north of Thalassery. The relics of their fort is located in the vicinity of Govt. Brennan College, Thalassery. Mabeli was converted to Islam and he accepted the name Muhammad Ali, who later became the first Arakkal Ali Raja.[3] [4][5][6] According to folklore, Cheraman Perumal went to Mecca from an erstwhile province named Poya Nadu(Governed by feudal governors named Randuthara Achanmar. The region comprises Edakkad, Anjarakkandy, Mavilayi etc.) now in Kannur district. Malik Deenar built a mosque in Madayi north of Kannur, the third oldest mosque in Kerala.[7]

Perumal's nephew Mabeli was an Arayankulangara Nair, and hence the Nair matrilineal system is observed by the Arakkal royal family.[8] His wife was the daughter of Kolathiri, and they later came to be known as Arakkal Beevi.[8] Muhammad Ali continued in the service of the Kolathiris even after his conversion, and his successors known as the Mammali Kidavus were the hereditary Padanairs of the Kolathiri.[8] Around this time, many Muslim merchant families became financially influential in the Malabar region. When the Arakkal family took control of Laccadives, they achieved near-royal status.

The British Military was very eager to make Dharmadam as their base and built a fort there. This small island village was strategically more secure than any surrounding place as it is a hilly island, however, it was governed by Arakkal kingdom, being the first Ali Raja's hometown. Arakkal kingdom was so powerful at that time as an ally of Mysore, even to defy the British. British East India Company was not allowed by the Arakkal kingdom to build a military garrison in Dharmadam. So they were forced to build their base in Thalassery where there was a strong presence of French forces stationed few kilometers away in Mahé.[2]

Location

[edit]The palace is three kilometers from Kannur, Kerala, India, in what is now called Kannur town. The Arakkal family was the only Muslim royal family in Kerala.

Ali Rajas and Arakkal Beevis

[edit]

The Arakkal family followed a matrilineal system of descent: the eldest member of the family, whether male or female, became its head and ruler. While male rulers were called Ali Rajas, female rulers were known as Arakkal Beevis.

Hameed Hussain Koyamma Ali Raja, became the new head of the Arakkal royal family on 2nd Dec 2021.[9]

Reigning Arakkal rajas and Arakkal beevis

[edit]The list of rulers of Arakkal:[10]

- Ali Raja Ali (1545–1591)

- Ali Raja Abubakar I (1591–1607)

- Ali Raja Abubakar II (1607–1610)

- Ali Raja Muhammad Ali I (1610–1647)

- Ali Raja Muhammad Ali II (1647–1655)

- Ali Raja Kamal (1655–1656)

- Ali Raja Muhammad Ali III (1656–1691)

- Ali Raja Ali II (1691–1704)

- Ali Raja Kunhi Amsa I (1704–1720)

- Ali Raja Muhammad Ali IV (1720–1728)

- Ali Raja Bibi Harrabichi Kadavube (1728–1732)

- Ali Raja Bibi Junumabe I (1732–1745)

- Ali Raja Kunhi Amsa II (1745–1777)

- Ali Raja Bibi Junumabe II (1777–1819)

History

[edit]There had been considerable trade relations between Middle East and Malabar Coast even before the time of Muhammad (c. 570 - 632 AD).[11][12] Muslim tombstones with ancient dates, short inscriptions in medieval mosques, and rare Arab coin collections are the major sources of early Muslim presence on the Malabar Coast.[citation needed] Islam arrived in Kerala, a part of the larger Indian Ocean rim, via spice and silk traders from the Middle East. Historians do not rule out the possibility of Islam being introduced to Kerala as early as the seventh century CE.[13][14] Notable has been the occurrence of Cheraman Perumal Tajuddin, the Hindu King that moved to Arabia from Dharmadom near Kannur to meet Muhammad and converted to Islam.[15][16][17] According to the Legend of Cheraman Perumals, the first Indian mosque was built in 624 AD at Kodungallur with the mandate of the last the ruler (the Cheraman Perumal) of Chera dynasty, who converted to Islam during the lifetime of Muhammad (c. 570–632).[18][19][20][21] According to Qissat Shakarwati Farmad, the Masjids at Kodungallur, Kollam, Madayi, Barkur, Mangalore, Kasaragod, Kannur, Dharmadam, Panthalayini, and Chaliyam, were built during the era of Malik Dinar, and they are among the oldest Masjids in the Indian subcontinent.[22] It is believed that Malik Dinar died at Thalangara in Kasaragod town.[23] According to popular tradition, Islam was brought to Lakshadweep islands, situated just to the west of Malabar Coast, by Ubaidullah in 661 CE. His grave is believed to be located on the island of Andrott.[24] The Arabic inscription on a copper slab within the Madayi Mosque in Kannur records its foundation year as 1124 CE.[25]

Thus history of Muslims in Kerala is closely intertwined with the history of Muslims in the nearby Laccadives islands. Kerala's only Muslim kingdom was Kannur's Arakkal family. Historians however, disagree about the time period of Arakkal rulers. They see the Arakkal kings come to power in the 16th or 17th century.

By 1909, Arakkal rulers had lost Kannur and the Cannanore Cantonment. By 1911, there was a further decline with the loss of chenkol (sceptre) and udaval (sword).[26] They allied and clashed with the Portuguese, the Dutch, the French and the British. The British played the biggest part in removing all vestiges of titles and power from the Arakkal rulers. One of the last kings, Abdu Rahiman Ali Raja (1881–1946), was active in helping his subjects. The last ruler was Ali Raja Mariumma Beevi Thangal. After her rule, the family broke up.

During the time of the Samuthiries the Muslims of Kerala played a major role in the local army and navy, as well as acting as ambassadors to Arabia and China. Even before this period they had settlements in Perumathura, Thakkala, Thengapattanam, Poovar and Thiruvankottu. Muslims from Pandi Desham migrated to trade with Aruvithura, Kanjirappalli, Mundakayam, Peruvanthanam, Muvattupuzha and Vandiperiyar in and around Kottayam district of Kerala. In the 17th century, trade links were established with places like Kayamkulam and Alappuzha in the west. It was during the time of Samuthiris that the title of Marakkar was created. Muslim influence reached its peak at the time of Kunjali Marakkar, the fourth in the line.

Thalassocracy in the Arabian Sea

[edit]The Arakkal Ali Rajas sure put their navy to good use. Ali Moossa, the fifth ruler is said to have conquered some of the Maladweep (Maldives) islands in 1183-84 CE. Generally, these Rajas were known by different titles, viz. Adi Raja (the first king), Azhi Raja (Lord of the seas), Aliraja (noble king), and Aali Raja, which shows the origin from the first king Mammali. The connection with the Maldives and Lakshadweep (Laccadives) was well-known to the Portuguese and other Europeans, with the 9° channel separating Minicoy from the Laccadive group being referred to as the 'Mammali’s Channel'. Even during the beginning of the 16th century, the king of Maldives was a tributary of this House. The Jagir of Laccadive islands, received by the Ali Rajas from Kolathiris in the 16th century, enhanced the status of the House.[27] Kannur (Cannanore) could effectively be characterised as a Muslim thalassocracy, acknowledging that the religious identity of the Ali Rajas had a significant role in their political prominence. A link can be made of the income from importing horses from West Asia to the political power of the Ali Rajas throughout the sixteenth century.[28]

Relations with the Kingdom of Mysore

[edit]After being appointed the Naval Chief of Hyder Ali's army, Ali Raja Kunhi Amsa II's first course of action was to capture the unfortunate Sultan of the Maldives Hasan 'Izz ud-din and present him to Hyder Ali after having gouged out his eyes, he had also defeated Sultan Muhammad Imaduddin III of the Maldives, who died in captivity.[29]

Foreign relations of the Arakkal

[edit]In the year 1777 a letter was sent to the Ottomans by Ali Raja Kunhi Amsa II, a dedicated ally of Hyder Ali of the Sultanate of Mysore and mentioned how the region received Ottoman assistance two hundred and forty years ago by Hadim Suleiman Pasha. Ali Raja Kunhi Amsa II also stated that the dynasty had been fighting for its authority for the last forty years against various hostile forces and also requested assistance against the British East India Company, two years later in 1780 another letter was sent by his sister Ali Raja Bibi Junumabe II requesting urgent assistance against Portuguese and British encroachments during the Second Anglo-Mysore War.[30]

Arakkal Museum

[edit]

The Durbar Hall section of the Arakkalkettu (Arakkal Palace) has been converted into a museum housing artifacts from the times of the Arakkal dynasty. The work was carried out by the Government of Kerala at a cost of Rs. 9,000,000. The museum opened in July 2005.

The Arakkalkettu is owned by the Arakkal Trust, which includes some members Arakkal royal family. The government had taken a keen interest in preserving the heritage of the Arakkal Family, which had played a prominent role in the history of Malabar. A nominal entry fee is charged by the Arakkal Trust.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Logan, William (2006). Malabar Manual, Mathrubhumi Books, Calicut. ISBN 978-81-8264-046-7

- ^ a b Malabar Manual, Volume 1, William Logan

- ^ Kerala Muslim History – P A Syed Mohammed

- ^ A. Sreedhara Menon (1967). A Survey of Kerala History. Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society. p. 204.

- ^ N. S. Mannadiar (1977). Lakshadweep. Administration of the Union Territory of Lakshadweep. p. 52.

- ^ Ke. Si. Māmmanmāppiḷa (1980). Reminiscences. Malayala Manorama Pub. House. p. 75.

- ^ "Madayi Mosque". Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Kerala District Gazetteers: Malappuram, A. Sreedhara Menon, Superintendent of Govt. Presses, 1972, p. 92

- ^ "Kerala: Head of Arakkal royal family dies | Kozhikode News - Times of India". The Times of India. 30 November 2021.

- ^ Truhart, Peter [in German] (23 October 2017). Regents of Nations / Regenten der Nationen, Part 2, Asia, Australia-Oceania / Asien, Australien-Ozeanien (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 1504. ISBN 978-3-11-161625-4.

- ^ Fuller, C. J. (March 1976). "Kerala Christians and the Caste System". Man. New Series. 11 (1). Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland: 53–70. doi:10.2307/2800388. JSTOR 2800388.

- ^ P. P., Razak Abdul "Colonialism and community formation in Malabar: a study of muslims of Malabar" Unpublished PhD thesis (2013) Department of History, University of Calicut [1]

- ^ Sethi, Atul (24 June 2007). "Trade, not invasion brought Islam to India". Times of India. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Katz 2000; Koder 1973; Thomas Puthiakunnel 1973; David de Beth Hillel, 1832; Lord, James Henry 1977.

- ^ Varghese, Theresa (2006). Stark World Kerala. Stark World Pub. ISBN 9788190250511.

- ^ Kumar, Satish (27 February 2012). India's National Security: Annual Review 2009. Routledge. ISBN 9781136704918.

- ^ Minu Ittyipe; Solomon to Cheraman; Outlook Indian Magazine; 2012

- ^ Jonathan Goldstein (1999). The Jews of China. M. E. Sharpe. p. 123. ISBN 9780765601049.

- ^ Edward Simpson; Kai Kresse (2008). Struggling with History: Islam and Cosmopolitanism in the Western Indian Ocean. Columbia University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-231-70024-5. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Uri M. Kupferschmidt (1987). The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine. Brill. pp. 458–459. ISBN 978-90-04-07929-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Husain Raṇṭattāṇi (2007). Mappila Muslims: A Study on Society and Anti Colonial Struggles. Other Books. pp. 179–. ISBN 978-81-903887-8-8. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Prange, Sebastian R. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press, 2018. 98.

- ^ Pg 58, Cultural heritage of Kerala: an introduction, A. Sreedhara Menon, East-West Publications, 1978

- ^ "History". lakshadweep.nic.in. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Charles Alexander Innes (1908). Madras District Gazetteers Malabar (Volume-I). Madras Government Press. pp. 423–424.

- ^ Kerala Source Book. India, Cruz Consultants for Kerala NRI Association, 2003. p25.

- ^ Kurup, KKN (1970). "Ali Rajas of Cannanore, English East India Company and Laccadive Islands". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 32: 44–53. JSTOR 44138504. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Prange, Sebastian. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast.

- ^ Logan, William. Malabar Manual. Vol. 1. p. 408.

- ^ Özcan, Azmi (1997). Pan-Islamism: Indian Muslims, the Ottomans and Britain, 1877-1924. BRILL. ISBN 9004106324.