Altoviti

A major contributor to this article appears to have a close connection with its subject. (November 2021) |

| Altoviti | |

|---|---|

| Noble family | |

| |

| Country | Florence, Italy |

| Founded | 1200 |

| Founder | Altovito Corbizzi (1200–1250) |

| Titles | Marquis Count Patriarch of Antioch Archbishop of Athens Archbishop of Fiesole Archbishop of Florence |

| Cadet branches | Altoviti Medici Altoviti Cybo Altoviti Avila Altoviti San Galletti |

The Altoviti are a prominent noble family of Florence, Italy. Since the medieval period they were one of the most distinguished banking and political families appointed to the highest offices of the Republic of Florence, friends and patrons of Galileo Galilei, Vasari, Raphael, and Michelangelo. They had a close personal relationship with the papacy. Through a predominant endogamous marriage policy they established alliances with dynasties of principal and papal nobility as the Medici, Cybo, Rospigliosi, Sacchetti, Corsini, and Aldobrandini.

Three popes have blood relations with the Altoviti; Innocent VIII, Clement IX and Clement XII. Pope Innocent VIII was the uncle of La Papessa Dianora Altoviti Cybo. Her son Bindo Altoviti became one of the most influential papal bankers and patron of the arts of the Renaissance. The Altoviti are still present and descendants continue to be involved in art and culture.

Origins

[edit]Pope Pius II presumed the family would be of Roman origin as in Fiesole was found a tomb with a Roman inscription quoting Furio Cammillo Altovita grandson of Furio Camillo, general, statesman and one of the most famous heroes of the early Roman Republic, honored with the title of Second Founder of Rome for his victory over the Gauls during the Gallic siege of Rome. According to the family legend, the silver Italian wolf on black background refers to the Roman origin of the family and is the mythical she-wolf Lupa Capitolina Romana who would have protected the founder of the dynasty Furio Camillo by devouring his enemies.[1]

Some believe the Altoviti were of Lombard heritage, descending from Tebalduolo Longobardo, baron and trusted advisor of king Alboin. The family came to Florence in the twelfth century. They engaged in the usual mix of culture, commerce (mainly wool and salt), banking and politics. Many were respected judges and diplomats in royal and papal courts. They belonged to the pro-papal elite of the Guelph faction. With an old military tradition, members of the family were considered supremely valiant captains in numerous decisive battles of the Florentine Republic. Therefore, scholars believe the heraldic wolf was granted by Emperor Frederick II as an award for brave captains.[2]

History, art, and culture

[edit]

In 1300 Rinaldo Altoviti was chosen with Dante Alighieri as chief of the Priors and possessed the supreme authority in the state. They were sent as ambassador to Boniface VIII to negotiate a truce between the rival Guelph factions cementing their position in the center of power of the Republic.[3] Bartolomea Altoviti was the wife of Salvestro de' Medici, Gonfalonier of Justice and cousin of Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, who established the Medicean domination in the affairs of Florence. Giovanna Altoviti married the rich merchant Benci Aldobrandini and became known as Madonna Aldobrandini. After her husband's death, she married the influential politician Giovanni Panciatichi.[4] One of their descendants was Giulio Rospigliosi, later Pope Clement IX. Still in 14th century, the family allied with the Salviati, Gucci, Pucci, Sacchetti and Bardi and became strong supporters of the war against Pope Gregory XI. The War of the Eight Saints contributed to the end of the Avignon Papacy, while Bardo Altoviti was one of the Eight Saints.[5]

In 1432 Oddo Altoviti married Giovanna Gherardini and their niece was Lisa Gherardini, identified as the model for Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. Oddo was named in the same year Gonfaloniere of Justice. He becomes an ally of Tommaso Soderini, father of Piero Soderini. Together with Luca Pitti, they use their influence to lift the ban of Cosimo de' Medici the Elder.[6] They established personal relationships and profitable links with the Papal Curia.

Antonio Altoviti married his cousin Dianora Altoviti Cybo. Known as La Papessa due to the influence she held over her uncle Giambattista Cybo, Pope Innocent VIII, Antonio was made papal Master of the Mint.[7] Like other Florentines banking families who provided loans to the popes in exchange for the rights to papal revenues, the Florentine, and Roman branch of the Altoviti prospected. The family supported the construction of the church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini and was a driving force behind the Compagnia della Misericordia. Some of the most famous members were Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci.[8]

As the Altoviti had family relationships with Cybo and Medici, and alliances with the della Rovere, Pope Julius II (Giuliano della Rovere) became a mentor to Antonio's son Bindo, as he was to his later papal successors Leo X (Giovanni de' Medici) and Clemente VII (Giulio de' Medici). Bindo was a close ally of his cousin Innocenzo Cybo, son of Maddalena de' Medici, the daughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent, and included among the young noblemen educated at the papal court, where he was in attendance of the hostage Federico Gonzaga, the son of Isabella d’Este and future duke of Mantua. During those years, he was introduced to Bramante, Raphael, and Michelangelo.

Bindo Altoviti's career flourished under the pontificate of Leo X and Clement VII. He was appointed as Depository General, the leading banker of the Papal States and chief commissioner for collecting taxes, mainly allocated for the reconstruction of the St. Peter's Basilica. After the death of Agostino Chigi and the sack of Rome in 1527, only a few wealthy banks had the capital to prevent economic chaos. Competing with fierce Genoese bankers and the Germans Fugger and Welser; the Strozzi, Salviati and Altoviti became the leading Florentine and curial bankers, given the chance to participate in massive credit transactions, controlling an enlarging sphere of papal finance.[9] Bindo's son Giovanni Battista Altoviti married Clarice Ridolfi, daughter of Lorenzo Ridolfi, grandson of Lorenzo il Magnifico de' Medici and Clarice Orsini, tighten the bond between the Altoviti and the houses of Medici and Strozzi.

Bindo Altoviti gradually expanded and diversified his financial activities, established dependences of the Altoviti Bank in foreign money markets as France, Netherlands, and England. Among his clients were duke Charles III of Savoy or king Henry II of France, and by shrewd political as well financial acumen he amassed one of the largest private fortunes in Italy. After the death of Clement VII and duke Alessandro de' Medici, the Altoviti sided with Catherine de' Medici and Pope Paul III, getting into an open confrontation with Cosimo I de' Medici.

One of Bindo's nieces became maid of honor of Catherine de' Medici. Before her marriage she was the mistress of the Duke of Anjou and future king Henri III of France. Another niece was one of the richest inhabitants of Marseille and mistress of Charles of Lorraine, Duke of Guise, governor of Provence. Her brother became the governor of Belle Ile and his godfather was Philippe Emmanuel of Lorraine, Duke of Mercœur, brother of the later Queen of France Louise of Lorraine, consolidating for the relationship with the royal court of France.

Bindo's son, Antonio was initiated to the ecclesiastical career, under the protection of one of the most authoritative Florentine prelates of the early sixteenth century, Cardinal Niccolò Ridolfi. Pope Paul III appointed Antonio Altoviti, as Archbishop of Florence. Furious by this open affront, Cosimo I retaliated by banning the new archbishop from setting foot in the city and even seized all the income and assets of the diocese.

After the death of Paul III (1549) Cosimo I lost no time in asking his successors to deliver the rebellious archbishop to him, but all refused. Nevertheless, within the next years, Cosimo I manifested a policy of rapprochement with the popes in anticipation of his request to obtain the title of Grand Duke. In 1564 Pope Pius IV, Giovanni Angelo de' Medici, asked Cosimo I to enforce the decree of the Council of Trent. Cosimo I responded to the plea by granting forgiveness to the Altoviti and writing to Antonio Altoviti, urging him to return to Florence to take command of his diocese and begin a process of reformation.

Antonio Altoviti finally took possession of the archdiocese in 1567. He entered the Florence with so much pomp, solemnity, and court of nobles, that Cosimo I was so irritated, understanding this triumphal event as a humiliation of his sovereign authority. Though in the same year Antonio Altoviti ordinated Cosimo's nephew Alessandro Ottaviano de' Medici and became his mentor. Alessandro Ottaviano de' Medici succeeded Antonio Altoviti as archbishop and became Pope Leo XI. The friendship between Antonio Altoviti and Alessandro Ottaviano de' Medici, continued the reconciliation between the Altoviti and the new ducal branch of the Medici. In 1569, Pius V finally conferred the title of grand duke of Tuscany on Cosimo I.

Bindo enjoyed the financial resources to undertake extensive renovations to the properties he inherited from his father including is suburban villa on the Tiber to indulge a growing passion for art. Known and endowed with a strong taste for art, he became a patron of the arts and friend to Vasari, Cellini, Raphael, and Michelangelo.[10]

Vasari frescoed the Triumph of Ceres in the main hall of the Villa Altoviti now shown in the National Museum of Palazzo Venezia.[11] For Bindo's suburban villa he also frescoed a vast loggia called the Vineyard decorated with statues and burial marbles from emperor Hadrian's Villa Adriana as he had bought most of the estate.[12] Andrea Sansovino also gave Bindo as a gift a terra-cotta model of the statue of St. Giovanni he sculptured for the Duomo in Florence.

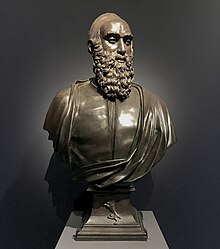

Immortalized by Raphael and Cellini, Bindo harbored Michelangelo when he fled from Florence to Rome.[13] Michelangelo had such a high esteem for him (while he despised his rival Agostino Chigi) that he gave him as a gift the cartoon of Noah's Blessing, used in the vault of the Sistine Chapel (lost) as well as a design of a Venus (lost) colored then by Vasari.[14]

In Florence on Piazza del Limbo they had a palazzo with a large family coat of arms on the façade and detained the patronage of the church Santi Apostoli. It was also Michelangelo who convinced Bindo, not to rebuild, but to preserve the church. Vasari painted the Allegory of the Immaculate Conception for the family chapel.[15] Bindo was buried in the church of Santa Trinità dei Monte in Rome and Giovanni Battista Naldini was commissioned to paint the cycle of frescoes concerning St. Giovanni the Baptist.

In the late 16th and 17th century, Alessandro Altoviti was the designated head of the Altoviti Bank in Rome. His brother-in-law was Giovanni Bonsi, Prime Minister of Ferdinando I de' Medici and created cardinal by Pope Paul V. The alliance with the Bonsi continued to stabilize the relationship between the Altoviti and the Medici and establishing a new alliance with the Borghese. Cardinal Bonsi also became a mentor to Iacopo Altoviti, who was later appointed Archbishop of Athens and Patriarch of Antioch by his close friend Pope Alexander VII.

Alessandro's daughter Francesca married Giovanni Battista Sacchetti, a trading partner of the Barberini family of Pope Urban VIII. The marriage had the effect of transferring to the Sacchetti financial resources, property including part of the collection of the Altoviti and profitable links with the curia, as well as client relations already established by the Altoviti.[16] Their son Giulio Cesare Sacchetti was an influential cardinal, supporter of Galileo Galilei and twice included in the French Court's list of acceptable candidates (papal conclave of 1644 and papal conclave of 1655) for the papacy. Their other son Marcello Sacchetti became papal treasurer to Urban VIII and his art agent. He continued to expand the family collection and became one of the most respected collectors of the Baroque and patron of Nicolas Poussin, Guido Reni and Pietro da Cortona. The family collection had over 800 paintings and later became the foundation for the Capitoline Museum in Rome.[17] Later the family inherited the principal titles of the Barberini and held until 1968 the hereditary title as Quartermaster General of the Sacred Apostolic Palace.

Their sister Clarice Sacchetti married her cousin Luigi Altoviti. Luigi was known as a skillful politician and became a senator as his father Alberto Altoviti or grandfathers Roberto Acciaioli and Niccolò Berardi, of the house of the Bosonids Counts of Marsi, before him. Their son Alberto Altoviti married Ottaviana de' Medici, cousin of Grand Duke Ferdinand II. Alberto was appointed senator and later Grand Chancellor of Tuscany. Emperor Ferdinand II elevated him to the title of Marquis of the Holy Roman Empire and later members of the family became actively involved in the Berlin salon culture.

Giulio Rospigliosi was a descendant of Giovanna Altoviti and created cardinal by Pope Alexander VII and succeed him as Pope Clement IX. He embellished the city of Rome with famous works commissioned to Bernini, including the angels of Ponte Sant'Angelo next to Palazzo Altoviti and the colonnade of Saint Peter's Basilica.

In the 18th century, Pope Clement XII also with blood ties to the Altoviti presided over the growth of a surplus in the papal finances. He thus became known for building the new façade of the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, beginning construction of the Trevi Fountain, and the purchase of Cardinal Alessandro Albani's collection of antiquities for the papal gallery. In his 1738 bull In eminenti apostolatus, he provides the first public papal condemnation of Freemasonry. One of the numerous Altoviti palazzos Florence was called dei Visacci with portraits of famous Florentine people such as Amerigo Vespucci, Francesco Guicciardini and Dante carved in the façade, and the halls frescoed by Lorenzo del Moro and Tommaso Redi. The palazzo became later home to the Florentine masonic lodge of the Grande Oriente d’Italia.

Giovambattista Altoviti was able to expand the family collection as he inherited at the request of his friend Pietro Paolo Avila, his palazzo in Rome together with his prestigious art collection and the name Avila was joined to the name Altoviti. When in the 19th century parts of the collection were sold, the portrait of Bindo Altoviti was sold to Ludwig I of Bavaria and the statues of the Villa Adriana to the Borghese family.

In the mid 19th century, descendants of the Altoviti married to the Radziwiłł family, magnates of Poland and Lithuania, instituting a relationship to the Imperial Court of Prussia. The Altoviti cultivated relationships with Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso, Edward Solly, Frédéric Chopin, Vincenzo Bellini, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Theodor Fontane. Later, they established relationships with other prominent individuals such as, Alexander von Humboldt, Franz Liszt, Ferdinand Lassalle, Fanny Lewald, Alexander von Humboldt, Paul Klee, or Hedwig Dohm, as their Berlin residence eventually became the Palais Pringsheim.

In the early 20th century, one descendant married a leading engineer involved in the Apollo space program and relative of Katja Mann, born Pringsheim wife of Thomas Mann. Contemporaneously, Prince Stanisław Albrecht Radziwiłł was one of the organizers of the Sikorski Historical Institute in London. He was married to Caroline Lee Radziwill, sister of the late First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, and sister-in-law of President John F. Kennedy.

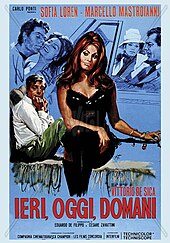

Marquis Antonio Altoviti Avila, married Maria Badoglio, daughter of Marshall of Italy Pietro Badoglio, Duke of Addis Abeba, Italian Ambassador to Brazil and first post-fascist Prime Minister of Italy. He produced the Academy Award-winning film Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow and the film Attila, while also contributing as a writer for The Thirteen Chairs.

Today, the descendants of the Altoviti remain active in various fields such as science, politics and culture, collaborating with Grammy and Academy-winning artist Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson of The Roots or Eumir Deodato.

Notable members

[edit]Frequently members of the family distinguished themselves in value, defending or serving the Florentine Republic holding prestigious public, political, military and religious offices.

- Giovanna Altoviti (1305–1395), known as Madonna Aldobrandini

- Iacopo Altoviti (1348–1403), Bishop of Fiesole

- Bardo di Altoviti (1342–1405), one of the Eight Saints

- Antonio Altoviti (1454–1507), papal banker and papal Master of the Mint

- Bindo Altoviti (1491–1557), papal banker and patron of the arts of the Renaissance

- Antonio Altoviti (1521–1573), Archbishop of Florence

- Giacomo Altoviti (1604–1693), Apostolic Nuncio to Venice, Patriarch of Antiochia and Archbishop of Athens

- Filippo Nero Altoviti (1634–1702), Bishop of Fiesole

- Antonio Altoviti Avila (1963, actor and producer, Academy Award-winning movie Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow)

References

[edit]- ^ Emil, O'Brien (2015). The Commentaries of Pope Pius II (1458–1464). Toronto University Press. p. 166.

- ^ Archivio della famiglia Altoviti

- ^ Santagata, Marco (2016). Dante – The Story of His Life. Harvard University Press. p. 63.

- ^ Passerini, Luigi (1871). Genealogia e Storia della Famiglia Altoviti. Cellini. p. 31.

- ^ Trexler, R. C. (1963). Renaissance News Vol. 16, No. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–94.

- ^ Passarini, Luigi (1871). Genealogia e storia della famiglia Altoviti. Cellini. p. 73.

- ^ von Reumont, Alfred. Geschichte der Stadt Rom: Dritter Band. Salzwasser Verlag. p. 401.

- ^ Polverini Fosi, Irene (1991). Pietà, devozione e politica: due confraternite fiorentine nella Roma del Rinascimento. Archivio Storico Italiano. p. 158.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ehrenberg, Richard (192). The Fuggers. Gustav Fischer. p. 274.

- ^ de Tolnay, Charles (1969). Michelangelo. Princeton University Press. p. 131.

- ^ Rubin, Patricia Lee (1995). Giorgio Vasari: Art and History. Yale University. pp. 11, 14, 117.

- ^ Rendina, Claudio. La grande enciclopedia di Roma. Newton & Compton. p. 62.

- ^ Goffen, Rona (2002). Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian. Yale University Press. p. 191.

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (1993). Vita di Michelangelo. Edizioni Studio Tesi. p. 118.

- ^ Giusti, Anna Maria (2006). Pierre Dure, The Art of Semiprecious Stonework. Thames & Hudson. p. 28.

- ^ Trevor Dean, & K. J. P. Lowe (1998). Marriage in Italy, 1300–1650. Cambridge University Press. p. 209.

- ^ Zirpolo, Lilian H. (2005). Ave Papa/Ave Papabile: The Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage, and Political Aspirations. CRRS Publications University of Toronto. p. 116.