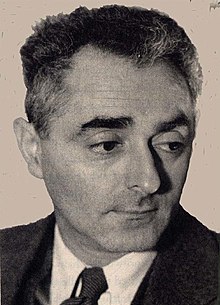

Albert Boni

Albert Boni | |

|---|---|

c. 1928 | |

| Born | October 21, 1892 New York City, United States |

| Died | July 31, 1981 (aged 88) Ormond Beach, Florida, United States |

| Education | Harvard (1 year), Cornell (2 years) |

| Occupation | Publisher |

| Years active | 1912–1974 |

| Notable work | Microprinting |

| Children | William, of Carmel, N.Y., and three granddaughters, Karin Fisher of St. Paul, Minn., Mariette Bock of Chester, Vt., and Nell Hughes of Rochelle Park, N. J.[1] |

| Parent(s) | Charles Boni Sr & Bertha Seltzer Boni, Her brother was Thomas Seltzer, their uncle and fellow publisher |

| Relatives | Charles F Boni |

Albert Boni (October 21, 1892 – July 31, 1981[2][3]) was co-founder of the publishing company Boni & Liveright and a pioneering publisher in paperbacks and book clubs.[1]

Biography

[edit]Born in 1892 to a Jewish family in New York City, Albert Boni moved, at an early age, with his family to Newark and completed his secondary school education there at Barringer High School.[4] He completed two years of college at Cornell University and one year at Harvard University. Instead of starting his senior year at Harvard, Boni convinced his father to finance the establishment (originally at 95 Fifth Avenue[5] and then at 135 MacDougal Street) of the Washington Square Bookshop[6] with Albert's brother Charles as a partner. The Boni brothers' book store became a meeting place for leftist, Greenwich Village writers and intellectuals. The Boni brothers, with two other partners, created the Little Leather Library of pocket-sized editions of literary classics bound in imitation leather. These editions were hugely successful – the Woolworth stores sold a million copies in one year. In 1913–1914, the Boni brothers published the short-lived literary magazine The Glebe. In 1914, Boni, with Lawrence Langner and others, founded the Washington Square Players.[1] In 1915, the Boni brothers sold the Washington Square Bookshop to Frank Shay.[7]

In 1917, Boni married Cornelia 'Nell' van Leeuwen, a widow with a young son, who was adopted by Boni upon the marriage.[8] With financial backing from Horace Liveright's father-in-law, paper executive Herman Elsas, the two partners Boni and Horace Liveright incorporated the publishing house Boni & Liveright on February 16, 1917. Boni & Liveright founded the Modern Library (originally called Modern Library of the World's Best Classics), which was eventually acquired by Random House. The Modern Library was financed by $25,000 from Felix M. Warburg and the Boni brothers' uncle Thomas Seltzer.[5] A year and a half after incorporating, Boni sold his interest in Boni & Liveright to Horace Liveright in 1919. However, the name of the firm remained "Boni & Liveright" until 1928, when the name of the publishing house was changed to "Horace Liveright, Inc."

Sometime between 1920 and 1925, the Boni brothers signed The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door at Frank Shay's Bookshop on Christopher Street. The door came to serve as an autograph book of notable 20th-century authors, artists, publishers, and other creatives. The door is now held by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, and Albert's signature can be found on front panel 2.[9]

In 1923, the Boni brothers purchased the publishing company Lieber & Lewis and renamed it the "Albert and Charles Boni Publishing Company." In 1926, they purchased the publishing business of their uncle, Thomas Seltzer. In 1929, the Boni brothers created Boni Paper Books, which offered one soft-cover book per month for 12 months for a yearly subscription price of $5. Boni Paper Books failed during the Great Depression. In 1939, Boni founded the Readex Microprint Corporation, a microfilm publisher of reference materials. When Boni retired in 1974, his only son, William, took over as president of Readex.[8] Boni died in Florida in 1981 and was survived by his wife, his son, and his son's three daughters.[1]

Microprint

[edit]While microphotography precedes microprint, microprint was conceived by Boni in 1934 when he was inspired by his friend, writer and editor Manuel Komroff who was showing his experimentation's related to the enlarging of photographs. It occurred to Boni that if he could reduce rather than enlarge photographs, this technology may enable publication companies and libraries to access much greater quantities of data at a minimum cost of material and storage space. Over the following decade, Boni worked to develop microprint, a micro-opaque process in which pages were photographed using 35mm microfilm and printed on cards using offset lithography. U.S. patent 2260551AU.S. patent 2260552A This process proved to produce a 6" by 9" index card which stored 100 pages of text from the normal sized publications he was reproducing. Boni began the Readex Microprint company to produce and license this technology. He also published an article A Guide to the Literature of Photography and Related Subjects (1943) which appeared in a supplemental 18th issue of the Photo-Lab Index.[10][11][12][13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mitgang, Herbert (August 1, 1981). "Albert Boni, Publisher, Dies; Founder of Boni & Liveright". NY Times.

- ^ Sterling, Guy (November 15, 2014). The Famous, the Familiar and the Forgotten: 350 Notable Newarkers. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4990-7991-3.

- ^ "Albert Boni in the Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998". Ancestry.com.

- ^ Imholtz, Jr., August A. (2006). Albert Boni: A Sketch of a Life in Micro-Opaque (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. pp. 253–277.

- ^ a b Imholtz, Jr, August (2006). "Albert Boni: A Sketch of a Life in Micro-Opaque" (PDF). American Antiquarian Society.

- ^ "..regarding the historic significance of 133–139 MacDougal St" (PDF). Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. May 2008.

- ^ "The Shop: The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door". norman.hrc.utexas.edu.

- ^ a b Albert Boni: An Inventor of His Readex Microprint Corporation Collection at the Harry Ransom Center

- ^ "Albert Boni: The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ^ Metcalf, K. D. (March 1, 1945). "The Promise of Microprint: A Symposium Based on The Scholar and the Future of the Research Library". College & Research Libraries. 6 (2): 170–183. doi:10.5860/crl_06_02_170. hdl:2142/35340. ISSN 2150-6701. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Erickson, Edgar L (March 1951). "Microprint: A Revolution in Printing". Journal of Documentation. 7 (3): 184–187. doi:10.1108/eb026173. ISSN 0022-0418.(subscription required)

- ^ Boni, Albert (Summer 1951). "Microprint" (PDF). American Documentation. 2 (3): 150. doi:10.1002/asi.5090020304. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ Raney, M. Llewellyn (April 1940). "The Minicam turns scholar". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 26 (2): 180–186. doi:10.1080/00335634009380548.

External links

[edit]- Bonibooks (Paper Books) at seriesofseries.com