Address of the International Working Men's Association to Abraham Lincoln

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

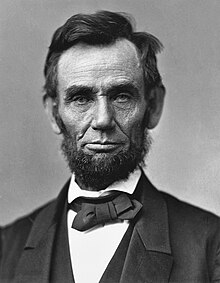

Address of the International Working Men's Association to Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America is a letter written by Karl Marx between November 22 to 29, 1864 that was addressed to then-United States President Abraham Lincoln by United States Ambassador Charles Francis Adams Sr.[1] The letter was written on behalf of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), an international organization of socialists, communists, anarchists and trade unionists.[1][2][3] In the letter, Marx congratulates Lincoln on his re-election victory in the 1864 United States presidential election and congratulates him and the Union for fighting against slavery in the United States.[1][2][4] Adams Sr. conveyed Lincoln's response to the letter, in which Lincoln briefly thanked the IWA for their support of the Union. The response was addressed to Randal Cremer, an abolitionist and trade unionist, although the response was also delivered to Marx and his friends.[3][4][5][6] The letter was among thousands of congratulatory letters received by Lincoln from abroad.[6]

The letter was first published in Germany on 30 December 1864 in Der Socialdemokrat, a German socialist publication, and was first published in English on January 7, 1865, in The Bee-Hive, a British trade unionist journal.[1]

Background

[edit]Shortly before and during the American Civil War, Marx became interested in and started writing about the struggles of American slaves and the issue of American slavery as it pertained to the Civil War.[2][4] Marx supported the Union in the Civil War, but argued that the Union would only win the war if they adopted more revolutionary abolitionist measures. Despite this support, there is no evidence that his commentary on the Civil War swayed British opinion on the war or assisted the Union war effort.[4][6] There is also evidence that Marx disliked Lincoln and the Union's cause unless they met Marx's objective of fomenting a communist revolution:[6][7]

The way in which the North is waging the war is none other than might be expected of a bourgeois republic, where humbug has reigned supreme for so long. The South, an oligarchy, is better suited to the purpose, especially an oligarchy where all productive labour devolves on the niggers and where the 4 million 'white trash' are flibustiers by calling. For all that, I'm prepared to bet my life on it that these fellows will come off worst, 'Stonewall Jackson' notwithstanding. It is, of course, possible that some sort of revolution will occur beforehand in the North itself.

— Karl Marx

While Marx and Lincoln held different opinions on businesses and wage labor, they both hated what they saw as exploitation and considered the value of labor to be more important than the value of capital.[4] However, Lincoln's labor advocacy was in favor of the free labor doctrine in particular, rather than the labor theory of value that Marx advocated for:[6]

The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him.

— Abraham Lincoln

In January 1860, Marx told his friend Friedrich Engels that the two most important things happening in the world were "on the one hand the movement of the slaves in America started by the death of John Brown, and on the other the movement of the serfs in Russia."[2] Marx equated slaveholders in the Southern United States with European aristocrats and argued that the end of slavery "would not destroy capitalism, but it would create conditions far more favorable to organizing and elevating labor, whether white or black."[2]

During the mid-19th century, Marx was friends with Charles A. Dana, an American socialist who was the managing editor of the New-York Tribune. Marx met Dana in Cologne, Germany in 1848, and in 1852, Dana hired Marx to be the Tribune's British correspondent. Marx would go on to write around 500 articles for the newspaper over the next decade, with most of them being published under his name. However, most of these articles were also brief news summaries about events in Europe, with only a small minority of the articles containing anything resembling Marxian economic analysis. Marx remained relatively unknown in the United States during the time he wrote these articles, with only a small number of contemporary newspapers noticing or reprinting Marx's Tribune articles. The newspapers that did reprint his articles suspected that the "Karl Marx" byline was a pseudonym used to expand on the output of other writers employed by the newspaper.[2][4][6]

Like several Republicans at the time, Lincoln was an "avid reader" of the Tribune, meaning it is possible that Lincoln had read Marx's articles during this time. Lincoln read the newspaper for its coverage of American politics and the Tribune's editorial stance supported the Republican and Whig economic doctrines of abolitionism, industrialisation, and protectionism in trade. During Lincoln's presidency, Marx urged Lincoln to take a more hardline stance against slavery in articles Marx wrote for the Tribune. In 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, giving Marx and the abolitionists what they wanted.[2][4][6]

Marx also wrote several articles for European newspapers during the Civil War. These articles explained what was at stake in the war, as well as arguing against the claim that slavery had nothing to do with the war. Marx argued that the war was also caused by Southern elites fearing that they were losing their power in American federal institutions.[4]

Contents

[edit]The letter starts by "congratulat[ing] the American people" upon Lincoln's re-election following his victory in the 1864 presidential election, adding that "If resistance to the Slave Power was the reserved watchword of your first election, the triumphant war cry of your re-election is Death to Slavery."[1][2]

The letter condemns "an oligarchy of 300,000 slaveholders" for tainting the United States and argued that the war against slavery would lift the working class of the country up in the same way that the American Revolutionary War did for the middle class.[1][2] The letter also says that the abolition of slavery would allow African-Americans to "attain the true freedom of labor".[1]

The letter ends by saying that Lincoln would "lead his country through the matchless struggle for the rescue of an enchained race and the reconstruction of a social world."[1]

Response

[edit]Lincoln's response starts by thanking the IWA for their support and declared that the defeat of the South would be a victory for all of humanity.[3][4]

The response declared that the United States would abstain from "unlawful intervention", but added that because nations exist to "promote the welfare and happiness of mankind by benevolent intercourse and example.", this motivated the country's conflict over slavery.[3][4]

Contemporary interpretations

[edit]In July 2019, Gillian Brockell, writing for The Washington Post, argued that Marx's letter to Lincoln, among other pieces of historical evidence, proved that "The two men were friendly and influenced each other", that "Lincoln was regularly reading Karl Marx", and that Lincoln "was surrounded by socialists and looked to them for counsel."[2]

Phillip W. Magness, writing for the American Institute for Economic Research (AIER), argued that Brockell's interpretation of the historical evidence is wrong, saying that she "badly misreads her sources and reaches faulty conclusions about the relationship between the two historical contemporaries. Contrary to her assertion, there is no evidence that Lincoln ever read or absorbed Marx's economic theories. In fact, it's unlikely that Lincoln even knew who Karl Marx was, as distinct from the thousands of well-wishers who sent him congratulatory notes after his reelection."[6]

In March 2022, Boyd Cathey, writing for the Abbeville Institute (an organization sympathetic to the Confederacy), argued that Lincoln's ties to Marx, including the letter from Marx addressed to Lincoln, "should be alarming for conservative Americans." and "for genuine believers in the Framers' Constitution."[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Marx, Karl (November 1864). "Address of the International Working Men's Association to Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brockell, Gillian (July 27, 2019). "You know who was into Karl Marx? No, not AOC. Abraham Lincoln". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Nichols, John (September 2011). "Reading Karl Marx with Abraham Lincoln". International Socialist Review. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Blackburn, Robin (August 28, 2012). "Lincoln and Marx". Jacobin. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ Blackburn, Robin. "Marx and Lincoln: An Unfinished Revolution" (PDF). Libcom.org. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Magness, Phillip W. (July 30, 2019). "Was Lincoln Really Into Marx?". American Institute for Economic Research. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ Marx, Karl (September 10, 1862). "Marx-Engels Correspondence 1862". History Is A Weapon. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ Cathey, Boyd (March 14, 2022). "Abraham Lincoln and the Ghost of Karl Marx". Abbeville Institute. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

External links

[edit]"Address of the International Working Men's Association to Abraham Lincoln" on the Marxists Internet Archive (English)