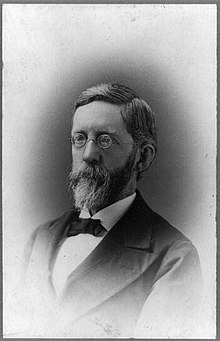

Adams Sherman Hill

Adams Sherman Hill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 30 January 1833 |

| Died | 25 December 1910 |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Journalist and academic |

| Employer | |

Adams Sherman Hill (30 January 1833 – 25 December 1910) was an American newspaper journalist and rhetorician. As Boylston Professor of Rhetoric at Harvard University from 1876 to 1904, Hill oversaw and implemented curriculum that came to effect first-year composition in classrooms across the United States. His most widely known works include The Principles of Rhetoric, Foundations of Rhetoric, and Our English.

Life and career

[edit]Hill was born in Boston, Massachusetts. After the death of his father in 1838 and his mother in 1846, Hill was raised by his uncle, Alonzo Hill.[1] His uncle encouraged Hill to become a minister, but he chose instead to attend Harvard, graduating with a law degree in 1855.[2] After working as a law reporter and night editor for the New York Tribune until 1872, he returned to Harvard to become an assistant professor of rhetoric.[3] In 1876, he was promoted to Boylston Professor of Rhetoric, a position he held until 1904.[4]

Reconstruction-Era education and culture

[edit]Hill's tenure as Boylston Professor coincided with a widely growing cultural desire for education in Reconstruction-Era America. The number of colleges in America, particularly small, religious colleges, rose rapidly after 1865, and universities across the country saw their student populations increase in turn.[5] As the industrial revolution began to move more and more people to cities, many individuals saw college as an opportunity to make themselves marketable for jobs.

This influx of students, coupled with the expanded number of composition programs across the country, meant that more and more teachers were brought in from secondary schools to teach these newly created composition classes. Overworked, teaching students who frequently needed more help with their compositions, (because they were generally not as classically educated as the “elite” students colleges had traditionally been set up to teach) composition instructors began to seek help in the form of textbooks. This cultural expansion, along with newly improved printing presses, helped give rise to the expanded usage of textbooks in American composition classrooms.[6]

At the same time, the use of newspapers became more widespread.[7] With the mass influx of newspapers meant more journalists, many who lacked college education, and in fact thought it unhelpful to their careers.[8] This highly consumed, but less educated style of writing clashed, however, with that of nineteenth-century intellectuals, who considered criticism vital to defining and upholding the standards of taste.[9] Because persons not considered "elite" had access to a large body of readers, intellectuals' authority, and thus importance, was deteriorating in American culture.[10]

Hill's views on culture sided him with the intellectuals of his time. As early as 1856, Hill vocalized about the dangers of "uneducated" newspaper journalists,[11] bemoaning the lack of control he as an "educated" man, was able to exert over the minds of his readers. By 1876, when Hill assumed the Boylston Professorship, it had already become cliche that the newspaper had replaced the rostrum and the pulpit.[12] During his time at Harvard, Hill saw the university as the place to educate individuals of the moral and linguistic dangers of journalism.[13]

Rhetorical theory

[edit]Much of Hill's writing focuses on rhetoric as a set of principles behind the skills of writing.[14] It always wasn't enough to be lectured, Hill required his students to practice their writing.[15] Hill's work was also heavily focused on grammar usage.

Hill's theories are deeply rooted in Current Traditionalist rhetoric, which at its heart involves a pedagogical focus on finding and correcting mechanical errors in writing.[16] Hill's theories also center on creating an American identity around a "properly used" English language, one that rejected "classical" standards of taste, and focused instead around a current understanding of English.[17]

The Principles of Rhetoric

[edit]In probably his most influential work,[18] Hill argues for a focus on rhetoric as an art, not a science. Therefore, The Principles of Rhetoric is only concerned with two elements: grammar and style. The text ignores Invention, and like many current traditional textbooks, places a heavy focus on exposition, which, according to the current-traditionalists, sets up the rational and empirical evidence in order to appeal to reason and understanding.[19] Hill's Principles follows this definition fairly strictly. He sees rhetoric as style, not substance; it doesn't offer any new meaning or understanding. Therefore, what one needs to understand is how to use rhetoric to create more intellectual arguments, not to generate new knowledge.

Much of the early focus in The Principles of Rhetoric is devoted primarily to Grammatical Purity. Hill offers many examples and rules on proper usage, including the three main ideas that language must be: reputable, national, and present.[20] Figurative language is considered inferior to exposition.

Hill also discusses the modes of writing in The Principles of Rhetoric, choosing to focus extensively on narration, description, and argumentation. Hill believed that movement and method in narration are “the life and logic of discourse”,[21] a view that his journalist background may have helped develop. Description brings "before the mind of the reader persons or things as they appear to the writer".[22] Argument and persuasion, for Hill, are closely linked, with persuasion acting as "an adjunct" to argument; its main emphasis on feelings, not intellect.[23]

Cultural impact

[edit]The substantial impact that The Principles of Rhetoric had was largely aided by Hill's position at Harvard, which, from 1875 to 1900, was the most influential English program in the United States.[24] Harvard’s university model was copied across the country, and Hill's words carried a lot of weight because he was the head of the Department of English. As a result, The Principles of Rhetoric remained in print from 1878 to 1923,[25] and current traditionalism was largely influential in English classrooms until the 1960s.[26]

Selected works

[edit]Beginnings of Rhetoric and Composition: Including Practical Exercises in English, New York: American Book Company, 1902.

Our English, New York: Chautauqua Press, 1890.

The Foundations of Rhetoric, New York: American Book Company, 1893.

The Principles of Rhetoric and Their Application, New York: Harper and Brothers, 1893.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Paine, Charles (1999). The Resistant Writer: Rhetoric as Immunity, 1850 to the Present. New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 90–91.

- ^ Bizzell and Herzberg (2001). The Rhetorical Tradition, 2nd Edition. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 1143.

- ^ Bizzell and Herzberg, 1143

- ^ "Death of Professor A. S. Hill '53". The Crimson. 3 January 1911.

- ^ Paine, "The Composition Course", 286

- ^ Connors, Robert (May 1986). "Textbooks and the Evolution of the Discipline". College Composition and Communication. 37 (2): 187. doi:10.2307/357516. JSTOR 357516.

- ^ Paine, "The Resistant Writer", 107

- ^ Paine, "The Resistant Writer", 109

- ^ Johnson, Nan (1991). Nineteenth-Century Rhetoric in North America. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 215.

- ^ Paine, "The Resistant Writer", 120

- ^ Paine, "The Resistant Writer", 94

- ^ Paine, Charles (Spring 1997). "The Composition Course and Public Discourse: The Case of Adams Sherman Hill, Popular Culture, and Cultural Inoculation". Rhetoric Review. 15 (2): 282–299. doi:10.1080/07350199709359220. JSTOR 465645.

- ^ Paine "The Resistant Writer" 134

- ^ Ried, Paul (1960). "The Boylston Chair of Rhetoric and Oratory". Western Speech. 24: 83–88.

- ^ Reid, Ronald (October 1959). "The Boylston Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory, 1806-1904: A Case Study in Changing Concepts of Rhetoric and Pedagogy". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 45 (3): 239–257. doi:10.1080/00335635909382357.

- ^ Berlin, James (1984). Writing Instruction in Nineteenth Century American Colleges. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 62.

- ^ Bizzell and Herzberg, 1143

- ^ Berlin, 67

- ^ Berlin, 66

- ^ Bizzell and Herzberg, 1143

- ^ Hill, Adams Sherman (1895). The Principles of Rhetoric. Harper and Brothers.

- ^ Hill, 248

- ^ Berlin 67

- ^ Jolliffe, David (1989). "The Moral Subject in College Composition: A Conceptual Framework and the Case of Harvard, 1865-1900". College English. 51 (2): 163–173. doi:10.2307/377432. JSTOR 377432.

- ^ Connors, 187

- ^ Berlin, 75