54th Ohio Infantry Regiment

| 54th Ohio Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

Memorial at Vicksburg National Military Park | |

| Active | October 1861 to August 15, 1865[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch | Infantry |

| Size | 200 |

| Engagements |

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

| Ohio U.S. Volunteer Infantry Regiments 1861-1865 | ||||

|

The 54th Ohio Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War. They wore Zouave[2] uniforms that were identical to those of the 34th Ohio Infantry Regiment (Piatts Zouaves.)[3][4]

Service

[edit]The 54th Ohio Infantry Regiment was organized at Camp Dennison near Cincinnati, Ohio, in October 1861[5] and mustered in for three years service under the command of Colonel Thomas Kilby Smith[6] as a Zouave regiment.[7] The regiment was recruited in Allen, Auglaize, Champaign, Clinton, Cuyahoga, Fayette, Greene, Highland, Lake, Logan, Morgan, and Preble counties.

While Col. Smith and his staff were still training the regimen, an army led by Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant won two battles that were the most significant Union victories, at that time, of the American Civil War,[8] the battles of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers respectively. These victories shut off the rivers to the Confederacy as transportation routes, and opened the way to restore federal authority at Nashville, an ironworks center, a major producer of gunpowder, a major supply depot, a major agricultural crop collection point, and a converging point for railroads.[9][note 1] Grant's Army of the Tennessee (AoT) continued its push into Confederate territory, Union troops arrived at the Tennessee River town of Savannah, TN, on March 11.[12] Within a week, a significant force was there and at landings further south. Meanwhile, the Army of the Ohio (AoO), under Buell, who had taken Nashville was moving southwest to join Grant's army force on the river.[13]

The Confederacy's defeats Fort Henry and Donelson made it abandon Kentucky and parts of Tennessee.[14] Their last troops in Nashville left on February 23.[15] Their Western Theater commander, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, made the controversial decision to quit the region, and despite political unhappiness in Richmond, his consolidation of troops further south precluded being could cut off in Kentucky and major portions of Tennessee.[16] He planned to consolidate forces in Corinth, MS just over the state line.[17][note 2] By the end of March, Johnston had over 40,000 Confederate troops at Corinth.

Realizing that its troops were too spread out, the War Department decided to concentrate troops at Pittsburg Landing,[19]9 miles (14 km) upriver (south) of Savannah, where the armies could advance on a good road to the rail center of Corinth, Mississippi.[20]

Shiloh

[edit]

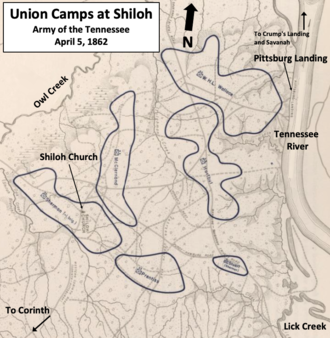

On Monday, February 17, 1862, the 850 men of the 54th Ohio Zouaves left Cincinnati via the Ohio River and sailed downriver reaching Paducah, KY, three days later, February 20. There, Col. Smith and his regiment were assigned to Col Stuart's 2nd Brigade in Brig. Gen. Sherman's 5th Division.[21][note 3] Two weeks later, March 6, the 54th Ohio boarded river steamers and sailed up the Tennessee River. After joining the AoT at Savannah from Wednesday through Friday, March 12-14, the 54th and its division disembarked at Pittsburg Landing Monday, March 17. After organizing itself at the landing, Sherman's division marched west 3 miles (4.8 km), and camped near Shiloh Church.[22] The men noted the army's position was somewhat shaped like a triangle, with the sides formed by various creeks and the river. The land was mostly wooded, with scattered cotton fields, peach orchards, and a few small structures.[23] They camped with their brigade to the east and left of the main Corinth road. The regiment spent the next fortnight in camp training, drilling, preparing for the expected advance, and patrolling south in the woods towards Corinth.[6] After a few days, the 54th as part of Stuart's brigade shifted camp closer to the Tennessee[24] at Bell Field to guard the ford over Lick Creek.[25]

In between the 54th Ohio and Sherman's three other brigades was Brig. Gen Prentiss' 6th Division, and between the Shiloh Church area and the river were Maj. Gen. McClernand's 1st Division and Brig. Gen. Hurlbut's 4th Division. Behind the 54th Ohio in Stuart's brigade and closest to the landing was Brig. Gen. W.H.L. Wallace's 2nd Division.[22][note 4]

The Union plan was to combine Grant's and Buell's armies and continue south[28] and capture Corinth, which would be a springboard to take Memphis, Vicksburg, and large portions of Confederate territory.[13] While most of the AoT was near Pittsburg Landing in early April, one division was 5 miles (8.0 km) downstream (north) at Crump's Landing, and the army headquarters remained further north in Savannah.[26] Buell's army was on the way from Nashville to Savannah.[16][note 5]

Johnston realized he could soon be outnumbered with 42,000 men at Corinth, and 15,000 more on the way,[note 6] while the not–yet–combined Union force could number 75,000 men.[28] Seizing the initiative, Johnston decided to surprise Grant on April 4 before Buell arrived from Nashville. Inexperience and bad weather caused the 20 miles (32 km) march north to take longer than he expected, and his troops were not in position until Saturday afternoon, April 5.[31] On Friday, April 4, pickets under Col. Ralph P. Buckland[32] made contact with some of Johnston's cavalry who drove them back to about a 1.5 miles (2.4 km) in advance of his center, on the 54th Ohio's right on the main Corinth road. Sherman sent his cavalry at them in pursuit driving them back about 5 miles (8.0 km).[25] The cavalry did not see the rest of Johnston's army, and Sherman and Grant were not concerned by their presence, with Sherman writing, "yet I did not believe that he designed anything but a strong demonstration."[33][25] This may have been fueled by lack of contact by other patrols such as the six companies Stuart sent out on the Hamburg road, with a squadron of cavalry sent forward by General McClernand, to reconnoiter beyond Hamburg on Saturday.[34]

The Confederates spent Saturday night, April 5 in the woods south of the Union campsites. Johnston's plan was to attack the Union left, pushing it northwest against the swampy land adjacent to Snake and Owl creeks. Confederate troops along the Tennessee River would prevent Union reinforcements and resupply.[35] Despite the cavalry skirmish on Friday,[36] the AoT did not expect a fight at that location and did not form a defensive line nor make any entrenchments.[37] Sherman dismissed the April 4 contact as a reconnaissance.[38] Grant had ordered all his commanders to be careful to avoid a battle before Buell arrived. [39] Further sightings and incidents throughout Saturday were likewise dismissed.[40] After hearing of sightings of Confederates at Seay Field, Col. Everett Peabody, commanding Prentiss' 1st Brigade, grew concerned, and around midnight Saturday, sent a five company patrol to investigate.[41] Prentiss was not informed, and the patrol advanced from their camp on the 54th Ohio's right southwest down a farm road leading to Pittsburg-Corinth Road.[42]

First Day's Battle

[edit]Around 5:00 a.m., Sunday, April 6, Confederate pickets from a battalion in Brig. Gen. Wood's 3rd Brigade of Maj. Gen. Hardee's 3rd Corps [note 7] of the battalion, where the Confederates opened fireleading to a fiece fight between these two small forces fighting for over an hour.[44][45]

By 5:30 a.m., Johnston and his staff heard the firing and ordered a general attack.[44] Keeping Beauregard in the rear directing men and supplies, he rode to the front to lead his men, effectively ceding control of the battle to Beauregard.[46][note 8] Meanwhile, Powell sent word back to Peabody that he was being driven back by an enemy force of several thousand.[48] Meanwhile Prentiss was outraged to learn Peabody had sent out a patrol and accused him violating Grant's order to avoid provoking a major engagement. However, he soon realized a large Confederate force was attacking and sent reinforcements forward.[49] The five-company patrol partially spoiled the Confederate element of surprise and gave Stuart's brigade on the AoT's left, and the rest of the army, time albeit brief to stand to arms and form up.[50] As the Zouaves and other regiments stood to arms, some Union commanders still were unconvinced that they were under attack, and Sherman himself was not convinced until his 7:00 a.m. ride to investigate the commotion near Rea Field.[51] In response, Sherman quickly and sent word to McClernand asking him to support his left and to Hurlbut, asking him to support Prentiss. [25][note 9] It became impossible for Johnston to control the intermingled units, so his corps commanders decided to divide the battlefield and lead their battlefield portion instead of their own corps.[53] The rebel attack went forward as a broad frontal assault.[54] Johnston and Beauregard did not put more strength on their right, which, fortunately for the 54th Ohio, meant they did not focus on turning the Union left.[55]

Grant, at his Savannah headquarters having breakfast, heard the distant sounds of artillery fire.[56] Grant was waiting for more of Buell's army to arrive in Savannah. Ahead of most of his divisions, Buell and his 4th Division under Brig. Gen. Nelson had already arrived in Savannah, and they were walking to Grant's headquarters when Grant departed by boat for Pittsburg Landing.[57] Grant ordered Nelson to march his division along the east side of the river to a point opposite Pittsburg Landing, where it could be ferried over to the battlefield.[58] Grant then took his steamboat, Tigress, south, stopping at Crump's Landing to tell Lew Wallace to get his division ready to move,[59] and Grant arrived at Pittsburg Landing around 9:00 a.m.[60][note 10] Grant rode inland and confirmed that Johnston had launched a full-scale attack. He sent a message to back to Lew Wallace at Crump's Landing to bring his division to the battlefield.[63][note 11]

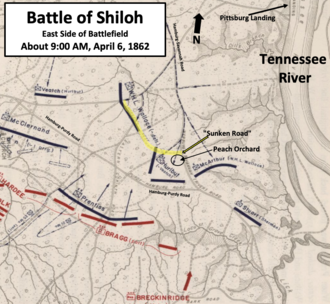

After initial contact, McLernand and Hurlbut had pushed forward in line with Sherman and behind Prentiss who was locked in a contest slightly forward of the rest of the AoT. The 54th Ohio in Stuart's brigade remained separated from Sherman on the extreme left of the AoT. At 7:30 a.m., Stuart received word from Prentiss that he had the enemy in his front in force followed by reports from his pickets that rebel infantry with artillery coming toward their position. Soon after that, Stuart saw the Pelican flag of Bragg's Louisiana troops advancing in the rear of Prentiss. He quickly sent his adjutant, 1st Lieut. Charles Loomis,[65] of the 54th Ohio, to tell Hurlbut Prentiss' left was turned, and to ask him to advance. Hurlburt replied thathe would advance immediately and within fifteen minutes one of Hurlbut's battery took position on the road immediately by Mason's 71st Ohio, Sturat's rightmost regiment, followed by the 41st Illinois in line on the right of this battery.[34] W.H.L. Wallace hadf seen the same gap and sent a brigade forward from the landing to fill a gap between Hurlbut's position at a peach orchard and Stuart's brigade.[66] Wallace's remaining brigades moved into positions near Duncan Field and what is now called the "Sunken Road," between McClernand's and Hurlbut's divisions.[67]

Meanwhile the Zouaves of the 54th Ohio had heard musketry early in the morning, but did not realize they were under attack until they heard artillery.[68] At 9:30 a.m., Johnston received reports that Union soldiers were deploying on his right flank. In response, he sent two brigades from Bragg's Corps there and called up Breckinridge's Reserve Corps. What his scouts had actually found was the 54th Ohio's and their brigade's camp.[69] Around 9:40 a.m., the 54th Ohio began receiving artillery fire, and twenty minutes later, they and their brigade were attacked by Confederate infantry.[70]

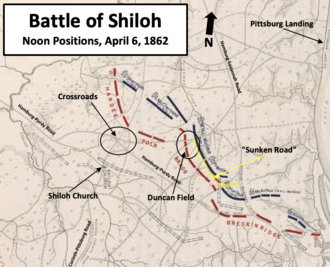

Stuart abandoned his camps and formed his line up on the north side of the ravine between the Savannah-Purdy Road and the river - 71st Ohio right, 55th Illinois center, and 54th left -with two companies of the 55th and two of the 54th out as skirmishers on the lower hills across the ravine overlooking the Savannah-Purdy Road. Meanwhile the Zouaves of the 54th Ohio had heard musketry on their right, but did not realize they were under attack until they heard artillery.[68] At 9:30 a.m., Johnston received reports that Union soldiers were deploying on his right flank, so he sent two brigades from Bragg's Corps there and called up Breckinridge's Reserve Corps. What his scouts had actually found was the 54th Ohio's brigade forming up.[69] Around 9:40 a.m., the Zouaves began receiving artillery fire, and twenty minutes later, they and their brigade were attacked by Confederate infantry who drove the skirmishers back to their regiments.[70] The Confederate onslaught gradually pushed the AoT's line back inflicting significant losses on the AoT,[71] but southeast of the Sunken Road, Stuart still held the Union left. Chalmers' and Jackson's brigades attacked Stuart's three regiments. When the rebels succeeded in placing the battery on the hills formerly occupied by his skirmishers, Stuart went in search of the battery on his right to counter it, but the battery and the infantry on its right had disappeared.[34]

He saw no organized units, only disorganized men streaming to the rear, between him and Hurlbut's troops. He could see a large body of the enemy's troops approaching and that his position would inevitably be flanked.[34] When he returned to his brigade, the enemy was making gains. The intensity of the fight increased around 11:15 a.m,, causing most of the 71st Ohio Infantry Regiment to flee to the rear.[72][note 12] Before he could reposition to cover their absence, the 55th Illinois and 54th Ohio were heavily engaged.[73]

As soon as possible, Stuart withdrew the remaining 800 men of the two regiments to a higher, more defensible position where they brought the rebels to a standstill. When rebel infantry tried to flanking his left through the woods by the Tennessee, Stuart extended his flank with four companies of the 54th under Major Cyrus W. Fisher,[65] who held them in check.[73] The two lines at the extreme left, about 150 yards (140 m) apart, fought for upwards of two hours. The rebels were protected by trees while within the grove, but an open, level, and smooth field lay between them and the four companies of Zouaves. Stuart knew he was outnumbered but fought on and held to keep the Confederates from advancing to the Tennessee, and secondly because he received a message from Brig. Gen. McArthur, commander of W. H. L. Wallace's 2nd Brigade. He had ridden forward from Pittsburg Landing to investigate in person, and promised to fill the gap on Stuart's right.[74]

During the action, the two regiments observed a battery to their southeast in position to enfilade their line, but it had little effect by firing too high. McArthur's promised support never appeared on their right. The men's ammunition was exhausted, and they had emptied the cartridge boxes of the killed and wounded, leading to a slackening of their fire.[75] Stuart was worried of a further rebel advance which could have easily shattered the survivors of the brigade. After consulting Smith and Malmborg, Stuart ordered a withdrawal back through the next ravine to a hill on their right. After an orderly retreat to that point, they found a rebel battery had moved up to a commanding position within 600 yards (550 m) on their left.[75] Stuart repositioned his remaining two regiments, but eventually they began panicking. When some men from the 54th Ohio broke and fled, Col. Smith went to the landing to bring them, and any other brigade members, back, leaving Lieut. Col. Farden in command.[72]

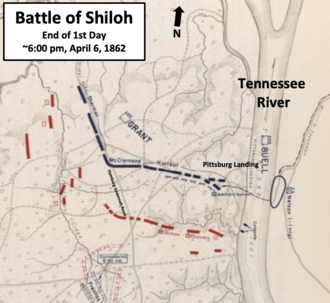

By noon, the Union right was a disorganized group of individual soldiers and portions of regiments. Still, Sherman and McClernand fought on with the remnants of their divisions. [76] The situation at the Union center was much better. Prentiss repelled multiple attacks,[77] and Confederate losses were considerable.[78] The Union left, even more so than the right, was pushed back. The 55th Illinois and 54th Ohio fought on and made several stands east of Bell Field against two of Bragg's brigades.[79] The continued shelling compelled Stuart to withdraw further, sheltering the command as well as possible by ravines and circuitous paths, finally reaching a cavalry camp just south of the landing where the brigade reformed.[75]

On their way, a small remnant of the 71st Ohio, under command of its adjutant, 1st Lieut. James H. Hart.[80] Fortunately for the 54th Ohio and the rest of the Union army, Bragg's hungry men had exhausted their ammunition and pillaged food from the Union camps instead of continuing the attack.[79] Finding the rebels had broken contact and fearing ammunition resupply would never reach his brigade, Stuart ordered the brigade to march to toward the landing. A quarter of a mile short of the batteries, one of Grant's staff officers stated that ammunition was on the way and ordered all movement to the rear stop.[75]

Although Stuart restored order, he was wounded in the shoulder and turned the command over to Smith, the next senior in rank, and went to the landing for treatment.[75] Smith temporarily left command fell to the 55th Illinois' Lieut. Col. Malmborg[81] as Smith went in search of Fisher's Zouaves who had become detached.[75]

Meanwhile Grant, passing by, ordered Malmborg to form a line near some batteries lined up south of the landing. Around 2:15 p.m., Smith returned with Major Fisher and his men and took command.[82] Through Malmborg's efforts, Smith commanded a line of over 3,000 men composed of the brigade augmented by remnants of other regiments who had retreated towards the landing.[75] At this point, Major George W. Andrews,[80] of the 71st, rejoined the brigade with about 150 men.[note 13] By 2:30 p.m., the 54th Ohio was done fighting for the day.[82] At this time, south of the battlefield, Johnston, the rebel commander had bled to death from wounds.[83] Much of the brigade who had broken had rallied and were in the last engagement near the batteries.[75] }}

Instead of bypassing Prentiss and Wallace in the Hornet's Nest, the Confederates spent time and resources assaulting them. Shortly after 4:00 p.m., realizing that they were going to be surrounded, Wallace began leading his division north, and 15 minutes later, he was mortally wounded as most of his division escaped encirclement.[84] By 4:45 p.m,, Prentiss was left alone,[85] and within 45 minutes Prentiss and his command were captured. [86]The Hornet's Nest bought Grant precious time to stabilize and prepare a defensive line from Pittsburg Landing to the Hamburg-Savannah Road and further north.[87][note 14]

Sherman commanded the right of the line, and McClernand took the center. On the left were the remnants of W.H.L. Wallace's and Hurlbut's division.[88] At the landing were 10,000 to 15,000 stragglers and noncombatants.[87] The line included the artillery bolstered by the two gunboats in the river.[89] Grant rode up and down the line, urging the men to keep firing at their enemy.[90] The 54th Ohio and its brigade regrouped back within these lines. The stabilization let Sherman reunite his division and he had Smith move the brigade down the line to take up his divison's left flank near the center of the line.[6]

Second Day's Battle

[edit]Commands

[edit]The regiment was attached to District of Paducah, Kentucky, to March 1862. 2nd Brigade, 5th Division, Army of the Tennessee, to May 1862.[6] 1st Brigade, 5th Division, Army of the Tennessee, to July 1862. 1st Brigade, 5th Division, District of Memphis, Tennessee, to November 1862. 1st Brigade, 5th Division, District of Memphis, Tennessee, Right Wing, XIII Corps, Department of the Tennessee, November 1862. 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, Right Wing, XIII Corps, to December 1862. 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, Sherman's Yazoo Expedition, to January 1863. 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, XV Corps, Army of the Tennessee, to July 1865. Department of Arkansas to August 1865.

The 54th Ohio Infantry mustered out of service on August 15, 1865, in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Affiliations, battle honors, detailed service, and casualties

[edit]Organizational affiliation

[edit]Attached to:[1]

- District of Paducah, KY, to March, 1862

- 2nd Brigade, 5th Division, Army of the Tennessee (AoT), to May, 1862

- 1st Brigade, 5th Division, AoT to July 1862

- 1st Brigade, 5th Division, District of Memphis, to November, 1862

- 1st Brigade, 5th Division, Right Wing XIII Corps (Old), AoT, November, 1862

- 1st Brigade, 2nd Division, Right Wing XIII Corps AoT, to December, 1862

- 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, XV Corps, AoT, to July, 1865

- Department of Arkansas to August, 1865.

List of battles

[edit]The official list of battles in which the regiment bore a part:[1]

- Battle of Shiloh

- Siege of Corinth

- Battle of Chickasaw Bayou

- Battle of Fort Hindman

- Battle of Champion Hill

- Siege of Vicksburg

- Siege of Jackson

- Battle of Missionary Ridge

- Atlanta Campaign

- Battle of Resaca

- Battle of Dallas

- Battle of New Hope Church

- Battle of Allatoona

- Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

- Battle of Atlanta

- Siege of Atlanta

- Battle of Jonesboro

- Battle of Lovejoy's Station

- Sherman's March to the Sea

- Carolinas Campaign

- Battle of Bentonville

Detailed service

[edit]The regiment's detailed service was as follows:[91]

1862

[edit]- Left Ohio for Paducah, Ky., February 17, 1862.

- Moved from Paducah to Savannah, Tenn., March 6–12, 1862.

- Expedition to Yellow Creek, Miss., and occupation of Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., March 14–17.

- Battle of Shiloh, Tenn., April 6–7.[92][5]

- Advance on and siege of Corinth, Miss., April 29-May 30.

- Russell's House, near Corinth, May 17.

- March to Memphis, Tenn., via LaGrange, Grand Junction and Holly Springs, June 1-July 21.

- Duty at Memphis until November.

- Expedition from Memphis to Coldwater and Hermando, Miss., September 8–13.

- Grant's Central Mississippi Campaign, "Tallahatchie March," November 26-December 13.

- Sherman's Yazoo Expedition December 20, 1862, to January 3, 1863.

- Chickasaw Bayou December 26–28, 1862.

- Chickasaw Bluff December 29.

1863

[edit]- Expedition to Arkansas Post, Ark., January 3–10, 1863.

- Assault and capture of Fort Hindman, Arkansas Post, January 10–11.

- Moved to Young's Point, La., January 17–21, and duty there until March.

- Expedition up Rolling Fork via Muddy, Steele's and Black Bayous and Deer Creek, March 14–27.

- Demonstrations on Haines and Drumgould's Bluffs April 29-May 2. Moved to join army in rear of Vicksburg, Miss., May 2–14, via Richmond and Grand Gulf.

- Battle of Champion Hill May 16.

- Siege of Vicksburg, Miss., May 18-July 4.[5]

- Assaults on Vicksburg May 19 and 22.

- Advance on Jackson, Miss., July 4–10.

- Siege of Jackson, Miss., July 10–17.

- Camp at Big Black until September 26.

- Moved to Memphis, Tenn., then march to Chattanooga, Tenn., September 26-November 21.

- Operations on Memphis & Charleston Railroad in Alabama October 20–29.

- Bear Creek, Tuscumbia, October 27.

- Chattanooga-Ringgold Campaign November 23–27.[93]

- Tunnel Hill November 23–24.

- Missionary Ridge November 25.[93]

- Pursuit to Graysville November 26–27.

- March to relief of Knoxville November 28-December 8.

- March to Chattanooga, Tenn., then to Bridgeport, Ala., Bellefonte, Ala., and Larkinsville, Ala., December 13–31.

1864

[edit]- Duty at Larkinsville, Ala., to May 1, 1864.

- Expedition toward Rome, Ga., January 25-February 5.

- Atlanta Campaign May 1 to September 8.

- Demonstration on Resaca May 8–13.

- Near Resaca May 13.

- Battle of Resaca May 14–15.[5]

- Movements on Dallas May 18–25.

- Operations on line of Pumpkin Vine Creek and battles about Dallas, New Hope Church and Allatoona Hills May 25-June 5.

- Operations about Marietta and against Kennesaw Mountain June 10-July 2.

- Assault on Kennesaw June 27.

- Nickajack Creek July 2–5.

- Chattahoochie River July 6–17.

- Battle of Atlanta July 22.

- Siege of Atlanta July 22-August 25.

- Ezra Chapel, Hood's 2nd sortie, July 28.

- Flank movement on Jonesboro August 25–30.

- Battle of Jonesboro August 31-September 1.

- Lovejoy's Station September 2–6.

- Operations in northern Georgia and northern Alabama against Hood September 29-November 3.

- March to the sea November 15-December 10.

- Siege of Savannah December 10–21.

- Fort McAllister December 13.

1865

[edit]- Campaign of the Carolinas January to April 1865.

- Salkehatchie Swamps, S.C., February 2–5.

- Cannon's Bridge, South Edisto River, February 9.

- North Edisto River, February 11–13.

- Columbia February 16–17.

- Battle of Bentonville, N.C., March 20–21.

- Occupation of Goldsboro March 24.

- Advance on Raleigh April 10–14.

- Bennett's House April 26.

- Surrender of Johnston and his army.

- March to Washington, D.C., via Richmond, Va., April 29-May 19.

- Grand Review of the Armies May 24.

- Moved to Louisville, Ky., June 2, thence to Little Rock, Ark., and duty there until August.

Casualties

[edit]The regiment lost a total of 233 men during service; 4 officers and 83 enlisted men killed or mortally wounded, 3 officers and 143 enlisted men died of disease.[91]

Commanders

[edit]- Colonel Thomas Kilby Smith - promoted

- Colonel Cyrus W. Fisher

- Lieutenant Colonel James A. Farden - commanded at the Battle of Shiloh after Col Smith succeeded to brigade command

- Major Robert Williams Jr. - commanded at the Battle of Missionary Ridge

- Private Henry G. Buhrman, Company E - Medal of Honor — Participating in a diversionary "forlorn hope" attack on Confederate defenses, May 22, 1863.

- Sergeant James Jardine, Company F - Medal of Honor — Participating in the same "forlorn hope."

- Private David Jones, Company C - Medal of Honor — Participating in the same "forlorn hope."

- Private Edward McGinn, Company K - Medal of Honor — Participating in the same "forlorn hope."

- Private Jacob Swegheimer, Company I - Medal of Honor — Participating in the same "forlorn hope."

- Private Edward Welsh, Company D - Medal of Honor — Participating in the same "forlorn hope."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The Union army increased its firepower in those battles by receiving assistance from ironclad U.S. Navy gunboats[10] that carried up to 13 artillery pieces. Grant, rewarded by promotion to major general making him senior to all generals in the Western Theater (between the Appalachian Mountains and Mississippi River) save Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck.[11]

- ^ The town of Corinth had strategic value because it was at the intersection of two railroads, including one that was part of the rail network used to move Confederate supplies and troops between Tennessee and Virginia.[18]

- ^ The brigade contained 55th Illinois (Lieut, Col. Oscar Malmborg)and the 71st Ohio (Col. Rodney Mason) as well as the 54th Ohio.

- ^ Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace 's 3rd Division was at Crump's Landing, five miles (8.0 km) downstream (north) of the Union campsites.[26] While on his mid-March mission to damage a railroad, his men learned that a large Confederate force was nearby. Because of this, his division remained near Crump's Landing. [27]

- ^ The Union army move from Nashville to Savannah was delayed by the slow construction of a bridge across the Duck River at Columbia. Eventually, one division forded the river before the bridge was completed, and that division would be the first to arrive in Savannah.[29]

- ^ Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn's small Confederate army of 15,000 men was ordered to Corinth, but would not arrive in time for the Battle of Shiloh.[30]

- ^ Hardee's corps like Breckenridge's had only three brigades unlike Polk's and Bragg's which had two divisions of three brigades each.CITEREFU.S._War_Dept.,_Official_Records,_Vol._10/1 opened fire on Powell's men in the southeast corner of James J. Fraley's 40-acre (16 ha) cotton field before withdrawing.[43] Unaware that rebel skirmish lines were already behind his left and right rear, Powell advanced within {from {convert

- ^ Under tremendous pressure to perform well after the losses in Tennessee,[30] Johnston thought he could make his army more effective by inspiring his inexperienced troops in person.[47]

- ^ After Johnston's 5:30 order for a general attack, it took an hour before all Confederate troops were ready. Another hour was lost skirmishing at Seay Field (close to Fraley Field) which reduced his advantage of surprise.[52] The Confederate army alignment was another issue that helped reduce the attack's effectiveness. Hardee's and Bragg's corps began the assault with their divisions in one line that was nearly 3 miles (4.8 km) wide.[53] At 7:30 a.m,, Beauregard sent Polk's and Breckinridge's corps forward on the left and right of the line, which only extended the line and diluted the effectiveness of the two attacking corps.[47]

- ^ Sources have slight differences for Grant's Pittsburg Landing arrival time. Cunningham says around 8:00 a.m.[61] Esposito says 8:30 a.m.[47] Daniel and McPherson say 9:00 a.m.[62] Chernow says Grant disembarked around 9:00 a.m.[56]

- ^ This order would be the subject of controversy, as Lew Wallace disputed where he was told to go and by what route, and claimed the copy of the order was lost.[64]

- ^ Col. Rodney Mason, commander of the 71st Ohio, fled to the rear, and many of his men followed him. His Lieut. Col. Barton S. Kyle was killed when he attempted to rally the regiment. After another incident that occurred in August 1862, Mason was cashiered.[72]

- ^ Andrews had rallied this group at the Tennessee riverbank, where he hailed the gunboats, relating them of the approach of the enemy.[75]

- ^ Daniels uses the term "Grant's Last Line" for Grant's defensive position in his map showing positions at 6:00 pm on the first day of the battle.[88]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Dyer (1908), p. 1522; Federal Publishing Company (1908), p. 393.

- ^ Center for Archival Collections (2008).

- ^ NPS 54th Regiment, Ohio Infantry (2007).

- ^ CWA, 54th Ohio Regiment Infantry (2016).

- ^ a b c d Roster Commission (1897), p. 2, Vol. V.

- ^ a b c d Reid (1868), p. 327, Vol. II.

- ^ Smith (1898), p. 11.

- ^ Shaara (2006), p. 5.

- ^ McPherson (1988), p. 393.

- ^ McPherson (1988), p. 392.

- ^ Chernow (2017), p. 186.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 71.

- ^ a b Chernow (2017), p. 195.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith 2007, p. 54.

- ^ McPherson (1988), p. 402.

- ^ a b Shaara (2006), p. 6.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 219.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 68.

- ^ Daniel (1997), pp. 104–105.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 70.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1, pp. 93–98, 100–108.

- ^ a b Esposito (1959), p. 32.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), pp. 85–87.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 131.

- ^ a b c d U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1, p. 248 - Report of Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, U. S. Army, commanding Fifth Division, April 10, 1862, pp.248-254

- ^ a b Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 222.

- ^ Gudmens & Combat Studies Institute (U.S.), Staff Ride Team (2005), p. 83.

- ^ a b McPherson (1988), p. 406.

- ^ Daniel (1997), pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b McPherson (1988), p. 405.

- ^ McPherson (1988), pp. 406–407.

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1, p. 89 - Report of Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, U. S. Army, commanding Fifth Division, April 5, 1862, pp.89-90

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 141.

- ^ a b c d U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1, p. 257 - Report of Col. David Stuart, Fifty-fifth Illinois Infantry, commanding Second Brigade, April 10, 1862, pp.257-260

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 224.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 223.

- ^ McPherson (1988), p. 408.

- ^ Shaara (2006), p. 8.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 138.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 137.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 142.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 144.

- ^ Daniel (1997), pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b Daniel (1997), p. 144.

- ^ NPS Fraley Field (2023).

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 226.

- ^ a b c Esposito (1959), p. 34.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 145.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 147.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 154.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 158.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 149.

- ^ a b Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 200.

- ^ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), pp. 224–226.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 119.

- ^ a b Chernow (2017), p. 200.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 158.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 242.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 174.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 175.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 159.

- ^ McPherson (1988), p. 409.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), pp. 159–160.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 160.

- ^ a b Reid (1868), p. 325, Vol. II.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 238.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), pp. 238–240.

- ^ a b Daniel (1997), p. 198.

- ^ a b Daniel (1997), pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b Daniel (1997), p. 199.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 241.

- ^ a b c Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 211.

- ^ a b U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1, p. 258 - Report of Col. David Stuart, Fifty-fifth Illinois Infantry, commanding Second Brigade, April 10, 1862, pp.257-260 Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEU.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1258" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1, pp. 258–259 - Report of Col. David Stuart, Fifty-fifth Illinois Infantry, commanding Second Brigade, April 10, 1862, pp.257-260

- ^ a b c d e f g h i U.S. War Dept., Official Records, Vol. 10/1, p. 259 - Report of Col. David Stuart, Fifty-fifth Illinois Infantry, commanding Second Brigade, April 10, 1862, pp.257-260

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), pp. 254–256.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), pp. 256–261.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b Daniel (1997), p. 200.

- ^ a b Reid (1868), p. 407, Vol. II.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 212.

- ^ a b Daniel (1997), pp. 223–224.

- ^ Daniel (1997), pp. 226–227.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 232.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 233.

- ^ Daniel (1997), p. 236.

- ^ a b Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 308; Daniel (1997), p. 237.

- ^ a b Daniel (1997), p. 247.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 308.

- ^ Cunningham, Joiner & Smith (2007), p. 322.

- ^ a b Dyer (1908), p. 1522.

- ^ Smith (1898), p. 13.

- ^ a b Reid (1868), p. 328, Vol. II.

- ^ CMOHS (2014).

- ^ VCOnline (2020).

Sources

[edit]- Cunningham, Edward; Joiner, Gary D. & Smith, Timothy B. (2007). Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 (1st ed.). New York, NY: Savas Beatie. p. 413-414. ISBN 978-1-932714-27-2. LCCN 2010292585. OCLC 312626871. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York, New York: Penguin Press. p. 1104. ISBN 978-1-59420-487-6. LCCN 2017027493. OCLC 989726874. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

- Daniel, Larry J. (1997). Shiloh: The Battle That Changed the Civil War. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-684-80375-3. LCCN 96051539. OCLC 36011722. OL 7721685M.

- Dyer, Frederick H. (1908). A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion (pdf). Des Moines, IA: Dyer Publishing Company. p. 1522. hdl:2027/mdp.39015026937642. LCCN 09005239. OCLC 1403309. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Eicher, David J.; McPherson, James M. & McPherson, James Alan (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War (PDF) (1st ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. p. 990. ISBN 978-0-7432-1846-7. LCCN 2001034153. OCLC 231931020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Esposito, Vincent J. (1959). West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York City: Frederick A. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8050-3391-5. OCLC 60298522. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Federal Publishing Company (1908). Military Affairs and Regimental Histories of New York, Maryland, West Virginia, And Ohio (PDF). The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861–65 – Records of the Regiments in the Union army – Cyclopedia of battles – Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers. Vol. II. Madison, WI: Federal Publishing Company. p. 393. hdl:2027/uva.x001496379. LCCN 09005239. OCLC 1086145633. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Gudmens, Jeffrey J.; Combat Studies Institute (U.S.), Staff Ride Team (2005). Staff Ride Handbook for the Battle of Shiloh, 6-7 April 1862 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. p. 170. OCLC 57007739. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - McPherson, James M. (1988). Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (PDF). Oxford History of the United States (1st ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 904. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7. OCLC 7577667.

- Roster Commission, Ohio (1897). 54th–69th Regiments—Infantry. Official Roster of the Soldiers of the State of Ohio in the War on the Rebellion, 1861–1865. Vol. V. Akron, OH: The Werner Ptg. and Mfg. Co. p. 828. OCLC 1744402.

- Reid, Whitelaw (1868). The History of Her Regiments, and Other Military Organizations. Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers. Vol. II. Cincinnati, OH: Moore, Wilstach, & Baldwin. p. 1002. ISBN 9781154801965. OCLC 11632330.

- Shaara, Jeff (2006). Jeff Shaara's Civil War Battlefields: Discovering America's Hallowed Ground. New York, New York: Ballantine Books. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-34546-488-0. LCCN 2005054589. OCLC 1267611677. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- Smith, Walter George (1898). Life and letters of Thomas Kilby Smith: Brevet Major-General, United States Volunteers, 1820-1887. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 487. OCLC 971016460.

- U.S. War Department (1880). Operations in Kentucky, Tennessee, North Mississippi, North Alabama, and Southwest Virginia. Mar 4-Jun 10, 1862. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. X-XXII-I. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 93–98, 100–108, 248, 253, 257–261, 841, 857. hdl:2027/coo.31924077730160. OCLC 427057.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "54th Ohio Regiment Infantry". The Civil War Archive. 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- "Battle Unit Details, 54th Regiment, Ohio Infantry". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. January 19, 2007. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Fraley Field". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2023. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Congressional Medal of Honor Society". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. CMOHS. 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- "Medal of Honor Recipients—sorted alphabetically". THE COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE TO THE VICTORIA & GEORGE CROSS. VCOnline. 2020. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- "Infantry Units: 54th Ohio Volunteer Infantry". www.bgsu.edu. Center for Archival Collections. 2019. Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2008-03-20.