2020s in European history

The history of Europe during the 2020s covers political events on the continent, other than elections, from 2020 to the present, culminating when the year 2029 ends.

International events in Europe

[edit]During the early 2020s, a major concern was the pandemic of Covid-19, and different concerns and restrictions, as countries sought ways to prevent or limit the spread of the disease.

The outcomes of European national elections varied, with shifts in political power and the emergence of new leaders. Issues such as immigration, economic policies (especially concerning with inflation), the invasion of Ukraine and its impacts played significant roles in shaping European political agendas. Populist movements continued to have an impact on European politics.[1] Some countries like Italy, the Netherlands and Slovakia experienced the rise of populist leaders and parties.[2]

History by country or other governmental entity

[edit]EU

[edit]EU executive leaders

[edit]

Ursula Gertrud von der Leyen (German: [ˈʊʁzula ˈɡɛʁtʁuːt fɔn deːɐ̯ ˈlaɪən] ⓘ; née Albrecht; born 8 October 1958) is a German politician, serving as the 13th president of the European Commission since 2019. She served in the German federal government between 2005 and 2019, holding positions in Angela Merkel's cabinet, most recently as federal minister of defence. She is a member of the centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its affiliated European political party, the European People's Party (EPP). On 7 March 2024, the EPP elected her as its Spitzenkandidat to lead the campaign for the 2024 European Parliament elections. She was re-elected to head the Commission in July 2024.[3]

Albrecht was born and raised in Brussels, Belgium, to German parents. Her father, Ernst Albrecht, was one of the first European civil servants. She was brought up bilingually in German and French, and moved to Germany in 1971 when her father became involved in German politics. She graduated from the London School of Economics in 1978, and in 1987, she acquired her medical license from Hanover Medical School. After marrying fellow physician Heiko von der Leyen, she lived for four years in the United States with her family in the 1990s. After returning to Germany she became involved in local politics in the Hanover region in the late 1990s, and she served as a cabinet minister in the state government of Lower Saxony from 2003 to 2005.

In 2005, von der Leyen joined the federal cabinet, first as minister for family affairs and youth from 2005 to 2009, then as minister for labour and social affairs from 2009 to 2013, and finally as minister for defence from 2013 to 2019, the first woman to serve as German defence minister.[4] When she left office she was the only minister to have served continuously in Merkel's cabinet since Merkel became chancellor. She served as a deputy leader of the CDU from 2010 to 2019, and was regarded as a leading contender to succeed Merkel as chancellor of Germany and as the favourite to become secretary general of NATO after Jens Stoltenberg. British defence secretary Michael Fallon described her in 2019 as "a star presence" in the NATO community and "the doyenne of NATO ministers for over five years".[5] In 2023, she was again regarded as the favourite to take the role.[6]

On 2 July 2019, von der Leyen was proposed by the European Council as the candidate for president of the European Commission.[7][8] She was then elected by the European Parliament on 16 July;[9][a] she took office on 1 December, becoming the first woman to hold the office. In November 2022 she announced that her commission would work to establish an International Criminal Tribunal for the Russian Federation.[11] She was named the most powerful woman in the world by Forbes in 2022, 2023 and 2024.[12][13][14]

On 18 July 2024, von der Leyen was re-elected as President of the European Commission by the European Parliament with an absolute majority of 401 members of the European Parliament out of 720. Her absolute majority was strengthened by around thirty votes compared to her election in 2019.[15]Austria

[edit]The Greens became a governing party for the first time in January 2020 as part of a coalition deal with the right-wing Austrian People's Party.[16] On 6 October 2021, Austrian anti-corruption prosecutors conducted a raid on the offices of Federal Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, the headquarters of the Austrian People's Party and the Federal Ministry of Finance.[17] Kurz has been accused of embezzlement and bribery, along with nine high-profile politicians and newspaper executives.[17] As a result of the raid, Kurz has sustained heavy criticism from his junior The Greens, as well as the opposition.[18] On 9 October 2021, Kurz announced his resignation,[19] with Alexander Schallenberg to serve as his replacement.[20] As a result of the resignation, Kogler announced his intention to continue the governing coalition.[20]

In the 2022 Austrian presidential election, incumbent Green president Van der Bellen was re-elected in the first round with 57% of the vote. Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) candidate Walter Rosenkranz placed second with 18% of the votes, a significant decline from the party's result in the 2016 presidential election.[21]

Belarus

[edit]

Presidential election

[edit]The 2020 Belarusian presidential election was held on Sunday, 9 August 2020. Early voting began on 4 August and ran until 8 August.[22] Incumbent Alexander Lukashenko was reelected to the sixth term in office, with official results crediting him with 80% of the vote. Lukashenko has won every presidential election since 1994,[23] with all but the first being labelled by international monitors as neither free nor fair.[24]

Opposition candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya claimed to have won a decisive first-round victory with at least 60% of the vote, and called on Lukashenko to start negotiations. Her campaign subsequently formed the Coordination Council to facilitate a transfer of power and stated that it was ready to organize "long-term protests" against the official results.[25][26] All seven members of the Coordination Council Presidium were subsequently arrested or went into exile. Numerous countries refused to accept the result of the election, as did the European Union, which imposed sanctions on Belarusian officials deemed to be responsible for "violence, repression and election fraud".[27]

Alexander Grigoryevich Lukashenko[b] (also transliterated as Alyaksandr Ryhoravich Lukashenka;[c] born 30 August 1954) is a Belarusian politician who has been the first and to date, only president of Belarus since the office's establishment in 1994,[29] making him the current longest-serving head of state in Europe.[30]

Before embarking on his political career, Lukashenko worked as the director of a state farm (sovkhoz) and served in both the Soviet Border Troops and the Soviet Army. In 1990, Lukashenko was elected to the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he assumed the position of head of the interim anti-corruption committee of the Supreme Council of Belarus. In 1994, he won the presidency in the country's inaugural presidential election after the adoption of a new constitution.

Lukashenko opposed economic shock therapy during the 1990s post-Soviet transition, maintaining state ownership of key industries in Belarus. This spared Belarus from recessions as devastating as those in other post-Soviet states and the former Eastern Bloc countries which prevented the rise of oligarchy. Lukashenko's maintenance of socialist economic model is consistent with the retaining of Soviet-era symbolism, including the Russian language, coat of arms and national flag. These symbols were adopted after a controversial 1995 referendum.

Subsequent to the same referendum, Lukashenko acquired increased power, including the authority to dismiss the Supreme Council. Another referendum in 1996 further facilitated his consolidation of power. Lukashenko has since presided over an authoritarian government and has been labeled by the media as "Europe's last dictator".[31] International monitors have not regarded Belarusian elections as free and fair, except for his initial win. The government suppresses opponents and limits media freedom.[32] This has resulted in multiple Western governments imposing sanctions on Lukashenko and other Belarusian officials.[33] Lukashenko's contested victory in the 2020 presidential election preceded allegations of vote-rigging, amplifying anti-government protests, the largest seen during his rule.[30] Consequently, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the United States do not recognise Lukashenko as the legitimate president of Belarus following the disputed election.[34][35]

Such isolation from parts of the West has increased his dependence on Russia, with whom Lukashenko had already maintained close ties despite some disagreements related to trade. This has been particularly the case following the rise to power of Vladimir Putin, replacing reformist president Boris Yeltsin. Lukashenko played a crucial role in creating the Union State of Russia and Belarus, enabling Belarusians and Russians to travel, work, and study freely between the two countries. He also reportedly played a crucial role in brokering a deal to end the Russian Wagner Group rebellion in 2023, allowing some Wagner soldiers into Belarus.[36]

Anti-government protests

[edit]The largest anti-government protests in the history of Belarus began in the lead-up to and during the election. Initially moderate, the protests intensified nationwide after official election results were announced on the night of 10 August, in which Lukashenko was declared the winner. Following the forced landing of Ryanair Flight 4978 to arrest opposition activist and journalist Roman Protasevich and his girlfriend Sofia Sapega, the European Union agreed to ban EU-based airlines from flying through Belarusian airspace, to ban Belarusian carriers from flying into EU airspace, and to implement a fresh round of sanctions.[37]

Border crisis

[edit]The 2021 Belarus–European Union border crisis was a migrant crisis manifested in a massive influx of Middle Eastern and African migrants (mainly from Iraq) to Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland via those countries' borders with Belarus. The crisis was triggered by the severe deterioration in Belarus–European Union relations, following the 2020 Belarusian presidential election, the 2020–2021 Belarusian protests, the Ryanair Flight 4978 incident, and the attempted repatriation of Krystsina Tsimanouskaya. The three EU nations have described the crisis as hybrid warfare by human trafficking of migrants, waged by Belarus against the European Union, and called on Brussels to intervene.[38][39]

Bulgaria

[edit]Protests

[edit]The 2020–2021 Bulgarian protests were a series of demonstrations held in Bulgaria, mainly in the capital Sofia, as well as cities with a large Bulgarian diaspora, such as Brussels,[40] Paris,[40] Madrid,[40] Barcelona,[40] Berlin[40] and London.[40] The protest movement was the culmination of long-standing grievances against endemic corruption and state capture, particularly associated with prime minister Boyko Borisov's governments, in power since 2009.

Elections

[edit]Snap parliamentary elections were held in Bulgaria on 11 July 2021 after no party was able or willing to form a government following the April 2021 elections.[41] The populist party There Is Such a People (ITN), led by musician and television host Slavi Trifonov, narrowly won the most seats over a coalition of the conservative GERB and Union of Democratic Forces parties. ITN's success was propelled primarily by young voters.

The 2022 Bulgarian parliamentary election was won by the conservative GERB with 25.3% of the vote. We Continue the Change (PP) came in second with 20.2% of the vote. Support for the far-right and ultranationalist Revival party significantly increased from 4.9% to 10.2%. It was the country's fourth general election in two years, after the collapse of the government led by Kiril Petkov in June.[42][43]

Croatia

[edit]In the 2020 Croatian parliamentary election, the conservative Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) emerged as the winner, securing the most seats in the parliament. The HDZ, led by Prime Minister Andrej Plenković, won 66 out of 151 seats in the Croatian Parliament, solidifying its position as the ruling party. The Social Democratic Party (SDP), the main opposition, trailed behind with 41 seats. Turnout was lower than in the last election, 46.3 percent compared to 52.6 percent in 2016.[44] Following the election, the HDZ successfully negotiated a coalition with smaller parties, including the Croatian People's Party (HNS), ensuring a parliamentary majority. The election addressed national issues, including economic recovery, healthcare reform, anti-corruption measures, and responses to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[45]

Czech Republic

[edit]In the 2021 Czech parliamentary election voters elected the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Republic. The three-party, center-right SPOLU coalition narrowly won the election with 27.8% of the vote. The populist ANO party of Prime Minister Andrej Babiš suffered a surprise defeat with 27.1% of the vote.[46] The liberal Pirates and Mayors (PirStan) electoral coalition came third with 15.6%. Right-wing Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) came fourth with 9.5%. The Social Democrats and the Communists, two of the ANO-led coalition government partners failed to reach the 5 percent threshold required to enter parliament.[47] After the results, SPOLU and PirStan signed a memorandum to form a coalition government with Petr Fiala as prime minister.[48]

In the 2023 Czech presidential election, retired general Petr Pavel defeated former prime minister and businessman Andrej Babiš with over 58% of the popular vote in the second round.[49] Petr Pavel, former chair of the NATO Military Committee, ran as an independent on a pro-Western, pro-European platform, and was backed by the centre-right governing alliance Spolu.[50] He won the first round of the election with 35.40% of the popular vote, ahead of Andrej Babiš, the former Czech prime minister running as the candidate of populist ANO 2011, who finished second with 34.99%.[51] Voter turnout in the second round was a little above 70%, the highest in a direct Czech presidential election and the highest in any national Czech election since 1998.[52][53]

Cyprus

[edit]The 2021 Cypriot legislative election was won by the Democratic Rally, a Christian-democratic party. The party won 27.77% of the popular vote, taking 17 seats in the parliament and remaining the party with the largest representation.[54] The left-wing Progressive Party of Working People came in second place with 22.34% of the vote and 15 seats in parliament. ELAM, an anti-migrant nationalist party, almost doubled its vote share compared to the 2016 election to about 6.8% of the vote, placing it fourth in voter preferences.[55]

In the 2023 Cypriot presidential election, centrist Nikos Christodoulides was elected President of Cyprus with 51.97% of the vote against left-wing Andreas Mavroyiannis with 48.03% on the second round.[56]

Denmark

[edit]In the 2022 Danish general election, the governing Social Democrats achieved their best result in 20 years, with 28% of the vote. Leading opposition party Venstre suffered major losses in the election, losing 20 seats in parliament. Two new parties standing in the elections, the Moderates and the Denmark Democrats, won 16 and 14 seats respectively, making them the third- and fifth-largest parties. The Social Liberals experienced one of their worst ever results with 7 seats in parliament from 16 in the last election.[57] After negotiations, a coalition government composed of the Social Democrats, Venstre and the Moderates was formed, the first time since 1977 where both main parties were part of a coalition government.[58]

Estonia

[edit]Kaja Kallas became the first female prime minister after the previous government fell after a corruption scandal.[59]

In the 2023 Estonian parliamentary election incumbent Prime Minister Kaja Kallas' center-right Reform Party was the clear winner with 31.2% of the vote and 37 seats in the Riigikogu.[60] In second place, the right-wing eurosceptic EKRE party won 16.1 percent of the vote. Support for the Centre Party, traditionally supported by Estonia's ethnic-Russian minority, fell to 14.7 percent from 23.1 percent in the last election.[61] The biggest surprise of the election was the emergence of Estonia 200, a centrist liberal pro-EU party and a parliament newcomer following the election. It won 13.3% of the vote and 14 seats in the Riigikogu.[62]

Finland

[edit]The government of Prime Minister Sanna Marin fell following the 2023 Finnish parliamentary election.[63] after her center-left Social Democratic Party (SDP) was narrowly defeated into third place in the 2023 Finnish parliamentary election by conservative and far-right challengers. The pro-business NCP gained 48 of the 200 parliamentary seats, narrowly defeating Marin's Social Democrats with 43 seats and the nationalist Finns Party with 46 seats.[64]

Following the election, a new right wing coalition government was formed by Petteri Orpo.[65] with the Finns Party and two additional small parties: the Swedish People's Party and the Christian Democrats.[66]

France

[edit]Islamism

[edit]The murder of Samuel Paty reignited the controversy surrounding depictions of Muhammad, and was followed by the 2020 Nice stabbing committed by another jihadist, as well as a far-right attack in Avignon on the same day.[67] Before the attacks, the Charlie Hebdo depiction had been republished on September 1, and the trial over the Charlie Hebdo shooting in 2015 had begun on September 2.[68] There had also been a second attack on Charlie Hebdo's former headquarters in Paris on September 25, and on October 2, President Emmanuel Macron had called Islam a 'religion in crisis'.[68] Following Macron's remarks, the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan suggested he needed "mental treatment", leading France to withdraw its ambassador.[69] Saudi Arabia and Iran condemned France, while tens of thousands marched against in protest in Bangladesh.[70] The French government demanded that the representative body for the religion in the country accept a 'charter of republican values', rejecting political Islam and foreign interference, as well as establishing a system of official licenses for imams.[71] Overseas, the French military intervention in the Sahel continued fighting against the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara.[72]

AUKUS reaction

[edit]On 17 September 2021, Macron and his foreign minister Jean-Yves Le Drian recalled the French ambassadors to the U.S. and Australia after the formation of the AUKUS defense technology between the U.S., Australia, and UK (from which France was excluded). As part of the 2021 security agreement, the U.S. decided to provide nuclear-powered submarines to Australia, to counter China in the Pacific and Indo-Pacific region, and Australia canceled a US$66 billion (A$billion) deal from 2016 to purchase twelve French-built conventionally powered (diesel) submarines.[73][74][75] The French government was furious at the cancellation of the submarine agreement and said that it had been blindsided, calling the decision a 'stab in the back'.[73][74][75] On September 22, Biden and Macron pledged to improve the relationship between the two countries.[76]

2022 presidential election

[edit]In the 2022 French presidential election, Emmanuel Macron was re-elected as the president of France, the first sitting French president to have been so in 20 years. In the second round of voting, Macron, a centrist, secured 58.5% of the vote over the nationalist-populist Marine Le Pen.[77][78]

In the first round of voting, Macron led by a margin of about four percentage points over Le Pen. In the first round of the 2017 election, Macron was ahead of Le Pen by just three percentage points. Far-left leader Jean-Luc Melenchon came in third, less than half a million votes from Marine Le Pen. Far-right polemicist Eric Zemmour came in fourth. Right-wing candidate Valerie Pecresse and green candidate Yannick Jadot each finished with less than 5% of the votes.[79]

The results of the first round showed a significant geographical divide between the three leading candidates. The incumbent, Emmanuel Macron's support was the strongest in large, affluent cities such as Toulouse and Paris, in addition to the west of France. Le Pen's strongest showings were in the post-industrial northeast, the south, and rural areas more broadly. Mélenchon's heartlands were in less prosperous suburbs around Paris, but otherwise he had relative success across the country.[80]

Protests

[edit]Thousands of people across France came to the streets in October 2022, launching a statewide strike against the rise in the cost of living. The demonstrations were described by Reuters as the "stiffest challenge" for Emmanuel Macron since his re-election in May 2022.[81] In March 2023, the French government used Article 49.3 of the constitution to force a pension reform bill, which would increase the retirement age from 62 to 64 years, through the French Parliament, sparking protests and two failed no confidence votes.

A further series of civil disturbances in France began on 27 June 2023 following the killing of Nahel Merzouk by a police officer in Nanterre, a suburb of Paris. Residents started a protest outside the police headquarters on 27 June, which later escalated into a riot as demonstrators set cars alight, destroyed bus stops, and shot fireworks at police.[82] By 29 June, over 150 people had been arrested,[83] 24 officers had been injured, and 40 cars had been torched.[84][85] Fearing greater unrest, Gérald Darmanin, Interior Minister of France, deployed 1,200 riot police and gendarmes in and around Paris, later adding an additional 2,000.

Macron Presidency

[edit]

Emmanuel Jean-Michel Frédéric Macron (French: [emanɥɛl makʁɔ̃] ⓘ; born 21 December 1977) is a French politician who has served as President of France since 2017. He previously was Minister of Economics, Industry and Digital Affairs under President François Hollande from 2014 to 2016 and deputy secretary-general to the president from 2012 to 2014. He has been a member of Renaissance since he founded it in 2016.

Born in Amiens, Macron studied philosophy at Paris Nanterre University. He completed a master's degree in public affairs at Sciences Po and graduated from the École nationale d'administration in 2004. He worked as a senior civil servant at the Inspectorate General of Finances and as an investment banker at Rothschild & Co. Appointed Élysée deputy secretary-general by President François Hollande shortly after his election in May 2012, Macron was one of Hollande's senior advisers. Appointed Minister of Economics, Industry and Digital Affairs in August 2014 in the second Valls government, he led a number of business-friendly reforms. He resigned in August 2016, in order to launch his 2017 presidential campaign. A member of the Socialist Party from 2006 to 2009, he ran in the election under the banner of En Marche, a centrist and pro-European political movement he founded in April 2016.

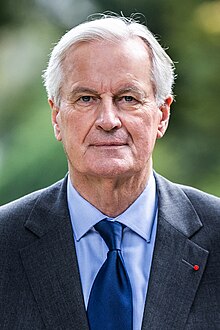

Partly as a result of the Fillon affair which sank the Republican nominee François Fillon's chances, Macron topped the ballot in the first round of voting, and was elected President of France on 7 May 2017 with 66.1% of the vote in the second round, defeating Marine Le Pen of the National Front. At the age of 39, he became the youngest president in French history. In the 2017 legislative election in June, his party, renamed La République En Marche! (LREM), secured a majority in the National Assembly. Macron was elected to a second term in the 2022 presidential election, again defeating Le Pen, thus becoming the first French presidential candidate to win reelection since Jacques Chirac defeated Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002. His centrist coalition lost its absolute majority in the 2022 legislative election, resulting in a hung parliament and the formation of France's first minority government since the fall of the Bérégovoy government in 1993. In early 2024, Macron appointed Gabriel Attal as Prime Minister, youngest head of government in French history and first openly gay man to hold the office, to replace Élisabeth Borne, the second female Prime Minister of France, after a major government crisis. Following crushing defeat at the 2024 European Parliament elections, Macron dissolved the National Assembly and called for a snap legislative election which resulted in another hung parliament and electoral defeat for his ruling coalition. It was only the third time in the French Republic's history that a president lost an election he called of his own initiative. 59 days after the election, Macron appointed Michel Barnier, a conservative political figure and former chief Brexit negotiator, as Prime Minister.

During his presidency, Macron has overseen several reforms to labour laws, taxation, and pensions; and has pursued a renewable energy transition. Dubbed "president of the rich" by political opponents, increasing protests against his domestic reforms and demanding his resignation marked the first years of his presidency, culminating in 2018–2020 with the yellow vests protests and the pension reform strike. In foreign policy, he called for reforms to the European Union (EU) and signed bilateral treaties with Italy and Germany. Macron conducted €40 billion in trade and business agreements with China during the China–United States trade war and oversaw a dispute with Australia and the United States over the AUKUS security pact. From 2020, he led France's response to the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination rollout. In 2023, the government of his prime minister, Élisabeth Borne, passed legislation raising the retirement age from 62 to 64; the pension reforms proved controversial and led to public sector strikes and violent protests. He continued Opération Chammal in the war against the Islamic State and joined in the international condemnation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

2024 government change

[edit]

The Barnier government (French: gouvernement Barnier) was the 45th government of France during the period of the French Fifth Republic. It was formed in September 2024 after President Emmanuel Macron appointed Michel Barnier as Prime Minister on 5 September, replacing Gabriel Attal. It was a caretaker government from 5 December until its dissolution on 13 December 2024.

On 5 September, Barnier was invited by Emmanuel Macron to "form a unity government".[87] With only 212 out of 577 seats in the National Assembly, the centre-right coalition began as one of the smallest minority governments in French history, having to rely in the lower house on support or neutrality from other parties, including the National Rally. Its taking office also marked the first time under the Fifth Republic a government had a majority in the Senate, but not in the National Assembly.[88]

On 4 December 2024, the Barnier government collapsed after the National Assembly passed a motion of no confidence in a 331–244 vote.[89] It was the first French government to be toppled by Parliament since 1962. Following the vote, Barnier and his government resigned the following day and continued as caretaker government until a new government was formed.[90][91]Germany

[edit]The 2021 German federal election made significant shifts in the German political landscape. With 25.7% of total votes, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) recorded their best result since 2005, and emerged as the largest party for the first time since 2002. The ruling CDU/CSU, which had led a grand coalition with the SPD since 2013, recorded their worst ever result with 24.1%, a significant decline from 32.9% in 2017. Alliance 90/The Greens achieved their best result in history at 14.8%, while the Free Democratic Party (FDP) made small gains and finished on 11.5%. The Alternative for Germany (AfD) fell from third to fifth place with 10.3%, a decline of 2.3 percentage points. The Left suffered their worst showing since their official formation in 2007, failing to cross the 5% electoral threshold by just over one-tenth of a percentage point. Nevertheless, the party was entitled to full proportional representation due to the fact that it won three direct constituencies.[92][93]

In terms of geographical distribution, the SPD made the most consequential gains in eastern Germany in addition to increasing their vote share in their traditional heartlands in the Rhineland and the northwest. Despite losing ground overall, the AfD made some gains in Thuringia and other parts of the east. The CDU saw its vote share almost everywhere, but their partner party in Bavaria, the CSU, proved slightly more resilient. In the east, Die Linke suffered big declines in Brandenburg and eastern Berlin. [94]

With a fifth grand coalition being dismissed by both the CDU/CSU and the SPD, the FDP and the Greens were considered kingmakers. On 23 November, following complex coalition talks, the SPD, FDP and Greens formalized an agreement to form a traffic light coalition, which was approved by all three parties. Olaf Scholz and his cabinet were elected by the Bundestag on 8 December.[95]

Scholz government

[edit]

Olaf Scholz (German: [ˈoːlaf ˈʃɔlts] ⓘ; born 14 June 1958) is a German politician who has been Chancellor of Germany since 2021. A member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), he previously served as vice chancellor in the fourth Merkel cabinet and as Federal Minister of Finance from 2018 to 2021. He was also First Mayor of Hamburg from 2011 to 2018, deputy leader of the SPD from 2009 to 2019, and Federal Minister of Labour and Social Affairs from 2007 to 2009.

Scholz began his career as a lawyer specialising in labour and employment law. He became a member of the SPD in the 1970s and was a member of the Bundestag from 1998 to 2011. Scholz served in the Hamburg Government under First Mayor Ortwin Runde in 2001 and became general secretary of the SPD in 2002, where he served alongside SPD leader and then-chancellor Gerhard Schröder. He became his party's chief whip in the Bundestag, later entering the First Merkel Government in 2007 as Federal Minister for Labour and Social Affairs. After the SPD moved into the opposition following the 2009 election, Scholz returned to lead the SPD in Hamburg. He was then elected deputy leader of the SPD. He led his party to victory in the 2011 Hamburg state election and became first mayor, a position he held until 2018.

After the Social Democratic Party entered the fourth Merkel government in 2018, Scholz was appointed as both minister of finance and Vice Chancellor of Germany. In 2020, he was nominated as the SPD's candidate for Chancellor of Germany for the 2021 federal election. The party won a plurality of seats in the Bundestag and formed a "traffic light coalition" with Alliance 90/The Greens and the Free Democratic Party. On 8 December 2021, Scholz was elected and sworn in as chancellor by the Bundestag, succeeding Angela Merkel.

As chancellor, Scholz has overseen Germany's response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Despite giving a restrained and timid response compared to many other Western leaders, Scholz oversaw a significant increase in the German defence budget, weapons shipments to Ukraine, and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline was put on hold. Three days after the invasion, Scholz set out the principles of a new German defence policy in his Zeitenwende speech. In September 2022, three of the four Nord Stream pipelines were destroyed. During the Israel–Hamas war, he authorized substantial German military and medical aid to Israel, and denounced the actions of Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups. In November 2023, the Federal Constitutional Court demanded budget cuts totaling €60 billion to ensure the government would not surpass debt limits as set in the constitution;[96] this proved a significant challenge for Scholz's cabinet and contributed to the 2023–2024 protests.[97]

On 6 November 2024, his government majority collapsed as he dismissed Christian Lindner from the post of Federal Minister of Finance and broke up the coalition agreement. On 16 December 2024, Scholz lost a vote of no confidence. On the same day, he requested the President of Germany to dissolve the Bundestag; the President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, did so and called out new elections for 23 February 2025.Greece

[edit]Following a surge of migrant arrivals from Turkey, Greece suspended all asylum applications in March 2020.[98] The freeze was lifted a month later.[99]

The 2021 Greek protests broke out in response to a proposed government bill that would allow police presence on university campuses for the first time in decades.

At the June parliamentary elections in 2023, the main center-right party in Greece, incumbent New Democracy performed strongly by securing an absolute majority. The political left struggled with the main opposition Syriza losing more than 20 seats and far-right minor parties like Victory and Spartans entered parliament for the first time, giving the Greek parliament its strongest rightward tilt since the restoration of democracy in 1974.[100][101]

Under the new voting system, which grants the winning party 50 additional seats, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis' New Democracy party was able to increase its double-digit advantage over its main challenger, the left-wing Syriza party, and win 158 seats in the 300-seat legislature.[102][103] Four minor new parties, mainly from the far right, succeeded in surpassing the 3 percent requirement to enter parliament.[104]

Premierships

[edit]

Kyriakos Mitsotakis (Greek: Κυριάκος Μητσοτάκης, IPA: [cirˈʝakoz mit͡soˈtacis]; born 4 March 1968) is a Greek politician currently serving as the prime minister of Greece since July 2019, except for a month between May and June 2023. Mitsotakis has been president of the New Democracy party since 2016. He is generally associated with the centre-right, espousing economically liberal policies.

Mitsotakis previously was Leader of the Opposition from 2016 to 2019, and Minister of Administrative Reform from 2013 to 2015. He is the son of the late Konstantinos Mitsotakis, who was Prime Minister of Greece from 1990 to 1993. He was first elected to the Hellenic Parliament for the Athens B constituency in 2004. After New Democracy suffered two election defeats in 2015, he was elected the party's leader in January 2016. Three years later, he led his party to a majority in the 2019 Greek legislative election.

Following the May 2023 Greek legislative election in which no party won a majority and no coalition government was formed by any of the parties eligible to do so, Mitsotakis called for a snap election in June. On 24 May 2023, as required by Greece's constitution, the Greek president Katerina Sakellaropoulou appointed Ioannis Sarmas to be the caretaker prime minister for the interim period.[105] In the June 2023 Greek legislative election, he once again led his party to a majority and was sworn in as prime minister, having received the order to form a government from the Greek president.[106][107][108][109]

During his terms as Prime Minister, Mitsotakis has received both praise and criticism for his pro-European, technocratic governance, austerity measures,[110] and his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece.[111][112] He has been credited with the modernization and digital transformation of the country's public administration,[113] and has been remarked for his overall management of the Greek economy, with Greece being named the Top Economic Performer for 2022 by The Economist,[114] which was in particular due to Greece in 2022 being able to repay ahead of schedule 2.7 billion euros ($2.87 billion) of loans owed to Eurozone countries under the first bailout it received during its decade-long debt crisis, along with being on the verge of reaching investment-grade rating.[115][116] He has been commended for furthering LGBT rights in Greece through the legalization of same-sex adoption and same-sex marriage in Greece.[117][118] He has also received both praise and criticism for his handling of migration, including aid from the European Union,[119] but criticism from journalists and activists for pushbacks, which his government has denied.[120] Additionally, Mitsotakis has received criticism for heightened corruption during his term,[121][122] as well as a deterioration of freedom of the press in Greece.[123][124][125] His term was impacted by the 2022 wiretapping scandal,[126] the Tempi Train crash,[127] and the wildfires in 2021 and 2023.[128][129][130] In 2024 he received criticism by the European Parliament in a resolution addressing concerns over the state of the rule of law in Greece.[131][132][133]Hungary

[edit]At the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary election voters elected the 199 members of Hungary's National Assembly. Viktor Orbán's right-wing Fidesz party won a fourth consecutive term, consolidating a super majority in the Assembly by gaining over two-thirds of seats. The scale of his victory shocked his opponents, who had united to challenge him as the United Opposition.[134]

Viktor Mihály Orbán[135] (Hungarian: [ˈviktor ˈorbaːn] ⓘ; born 31 May 1963) is a Hungarian lawyer and politician who has been Prime Minister of Hungary since 2010, previously holding the office from 1998 to 2002. He has also led the Fidesz political party since 2003, and previously from 1993 to 2000. He was re-elected as prime minister in 2014, 2018, and 2022. On 29 November 2020, he became the country's longest-serving prime minister.

Orbán was first elected to the National Assembly in 1990 and led Fidesz's parliamentary group until 1993. During his first term as prime minister and head of the conservative coalition government, from 1998 to 2002, inflation and the fiscal deficit shrank, and Hungary joined NATO. After losing reelection, however, Orbán led the opposition party from 2002 to 2010.

Since 2010, when he resumed office, his policies have undermined democracy, weakened judicial independence, increased corruption, and curtailed press freedom in Hungary.[136][137] During his second premiership, several controversial constitutional and legislative reforms were made, including the 2013 amendments to the Constitution of Hungary. He frequently styles himself as a defender of Christian values in the face of the European Union, which he claims is anti-nationalist and anti-Christian. His portrayal of the EU as a political foe—as he accepts its money and funnels it to his allies and relatives—has led to accusations that his government is a kleptocracy.[138] It has also been characterized as a hybrid regime, dominant-party system, and mafia state.[139][140][141][142]

Orbán defends his policies as "illiberal Christian democracy."[143][144] As a result, Fidesz was suspended from the European People's Party from March 2019;[145] in March 2021, Fidesz left the EPP over a dispute over new rule-of-law language in the latter's bylaws.[146] His tenure has seen Hungary's government shift towards what he has called "illiberal democracy," while simultaneously promoting Euroscepticism and opposition to liberal democracy and establishment of closer ties with China and Russia.[147][148]Italy

[edit]Government crisis

[edit]During the 2021 Italian government crisis, the Conte II Cabinet fell after Matteo Renzi, leader of Italia Viva (IV) and former Prime Minister, that he would revoke IV's support to the government of Giuseppe Conte.[149] On 18 and 19 January, Renzi's party abstained and the government won the key confidence votes in the Chamber and in the Senate, but it failed in reaching an absolute majority in the Senate.[150] On 26 January, Prime Minister Conte resigned from his office, prompting President Sergio Mattarella to start consultations for the formation of a new government. On 13 February, Mario Draghi was sworn in as prime minister, leading to the Draghi Cabinet.[151] During the 2022 Italian government crisis on 14 July, despite having largely won the confidence vote, Prime Minister Draghi offered his resignation, which was rejected by President Sergio Mattarella.[152][153][154] On 21 July, Draghi resigned again after a new confidence vote in the Senate failed to pass with an absolute majority, following the defections of M5S, Lega, and Forza Italia;[155][156][157] President Mattarella accepted Draghi's resignation and asked Draghi to remain in place to handle current affairs.[158] A snap election was called for 25 September 2022.[159]

2022 presidential election

[edit]

The 2022 Italian presidential election was held in between 24 and 29 January 2022 and culminated in incumbent president Sergio Mattarella being confirmed for a second term, with a total of 759 votes out of 1009 on the eighth ballot.[160] This was the second most votes ever received by a presidential candidate. Mattarella became the second president to be re-elected, his predecessor Giorgio Napolitano being the first. The president of Italy was elected by a joint assembly composed of the Italian Parliament and regional representatives. The election process extended over multiple days.[161]

2022 general election

[edit]The 2022 Italian general election, which saw record-low voter turnout, was won by the centre-right coalition, headed by the Brothers of Italy party with their leader Giorgia Meloni.[162] Meloni was sworn as Italy's first female prime minister as well as the furthest right wing leader of the country since Mussolini.[163][164]

Ireland

[edit]The 2020 Irish general election was called following the collapse of the Fine Gael-led minority government, led by Prime Minister Leo Varadkar, in January 2020. The election resulted in a historic win for the left-wing nacionalist Sinn Féin, making it the second largest party of the Dáil Éireann.[165] The result was seen as a historic shift in Ireland's political landscape, effectively ending the two-party system of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil.[166] Sinn Féin secured the most first-preference votes, winning 37 seats. Fianna Fáil won 38 seats, and Fine Gael won 35 seats. The Green Party, which focused on environmental issues, increased its representation significantly from 2 seats to 12 seats in parliament.[167] The reason for the electoral upset for these parties was believed to be in voter dissatisfaction on issues of health, housing and homelessness.[168] On 27 June 2020, Micheál Martin was elected as Taoiseach, in an historic coalition agreement that saw his party Fianna Fáil go into government with the Green Party and Fianna Fáil's historical rivals, Fine Gael.[169][170]

In 2023 immigration became a large issue in Ireland following a mass stabbing in Dublin and rioting in response.[171][172] In 2024, diplomatic relations with Israel soured amid the conflict in the Middle East.[173][174] The role of Taoiseach moved to Simon Harris in April 2024.[175] 2024 was a big year for Irish politics with a general election, local elections and constitutional referendums being held throughout the year.[176] Following the general election, makeup of the different parties in the 34th Dáil remained similar but Fianna Fáil performed strongly against their coalition partners in Fine Gael.[177] As a result Harris tendered his resignation.[178]

Irish governments

[edit]There have been three governments of the 33rd Dáil to date, being coalition governments of Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Green Party. This followed the 2020 general election to Dáil Éireann held on 8 February, and negotiations on a programme for government that lasted till June. The parties agreed on a rotation, with the two major party leaders alternating as Taoiseach.[179][180] The makeup of the parties resulted in a centre-right coalition.[181] It was the first time that Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael have participated in the same government, which Leo Varadkar described as the end of what has often been referred to as Civil War politics.[182][183]

The 32nd government of Ireland (27 June 2020 to 17 December 2022) was led by Micheál Martin, leader of Fianna Fáil, as Taoiseach, and Leo Varadkar, leader of Fine Gael, as Tánaiste. It lasted 906 days.

The 33rd government of Ireland (17 December 2022 to 9 April 2024) was led by Varadkar as Taoiseach and Martin as Tánaiste. It lasted 480 days. Varadkar resigned as leader of Fine Gael on 20 March 2024 and was succeeded on 24 March by Simon Harris. Varadkar resigned as Taoiseach on 8 April.[184]

The 34th government of Ireland (9 April 2024 to present) is led by Simon Harris as Taoiseach and Martin as Tánaiste. It has lasted 287 days to date. Harris resigned as Taoiseach on 18 December 2024 on the morning of the first meeting of the 34th Dáil after the 2024 general election. Harris and the other members of the government will continue to carry out their duties until the appointment of their successors.Kosovo

[edit]Triggered by the Government of Kosovo's decision to reciprocally ban Serbian license plates, a series of protests by Serbs in North Kosovo—consisting mostly of blocking traffic near border crossings— began on 20 September 2021. During the crisis, two government vehicle registration centers in Zvečan and Zubin Potok were targeted by arsonists. The protests caused relations between Serbia and Kosovo—which had been improving—to worsen, and led to the Serbian Armed Forces being placed on heightened alert. On 30 September, an agreement was reached to end the license plate ban, taking effect on 4 October. In return, the protesters agreed to disperse. Pursuant to the terms of the agreement, Kosovar license plates in Serbia and Serbian license plates in Kosovo had their national symbols and country codes covered with a temporary sticker.

Beginning on 31 July 2022, tensions between Serbia and Kosovo heightened again due to the expiration of the eleven-year validity period of documents for cars on 1 August 2022, between the government of Kosovo and the Serbs in North Kosovo. On 26 May 2023, Kosovo took control of the North Kosovo municipal buildings by force, to enable the newly elected ethnic Albanian mayors to physically assume office, as they had won the 23 April local elections – based on an extremely low number of votes, due to an election boycott by the Serb population. A civil disturbance occurred, and Serbia put its armed forces on alert. The decision of Kosovo to use force was condemned by the United States and the EU.

Latvia

[edit]The 2022 Latvian parliamentary election resulted in a historic defeat of the centre-left Harmony party which lost all of its parliamentary seats after failing to surpass the electoral threshold of 5%.[185] It traditionally represented Latvia's Russian minority and was the largest political group in Saeima since the 2011 Latvian parliamentary election. The New Unity party led by the incumbent Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš won the most votes.[186] Kariņš subsequently formed a centre-right coalition with the United List and the National Alliance and was re-elected as prime minister for the second term.[187]

On 31 May 2023, Edgars Rinkēvičs, Latvia's long-serving Minister of Foreign Affairs, was elected new President of Latvia, becoming the EU's first openly gay head of state.[188] His candidacy was supported by his own party New Unity and two opposition parties – Union of Greens and Farmers and The Progressives. This undermined the stability of governing coalition and eventually resulted in the collapse of second Kariņš' cabinet on 14 August 2023.[189]

On 15 September 2023, the Saeima approved the new government, headed by Evika Siliņa, a former lawyer who previously served as a Minister of Welfare.[190] She became the second-ever female to hold the position of Prime Minister, following Laimdota Straujuma in 2014–2016. Her appointment also marked a historic moment, with all three Baltic states, including Estonia and Lithuania, being led by female prime ministers.[191] The new coalition was labelled by some as the "first-ever centre-left" government since the restoration of independence in 1991.[192] On 9 November 2023, the Saeima adopted amendments to eight laws envisaging the introduction of a new Partnership institution in Latvia which will grant cohabiting adults, including same-sex partnerships, a degree of legal recognition and protection, starting from 1 July 2024.[193] The same month, the parliament ratified the Istanbul Convention.[194]

Lithuania

[edit]In the Lithuanian parliamentary election of October 11, 2020, the Homeland Union, a center-right party, emerged as the largest party in the Seimas.[195] Coalition negotiations ensued, leading to the formation of a new government under Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė, which became the second-ever female Prime Minister of Lithuania in 2020.[196] The coalition included the Homeland Union, the Liberal Movement, and the Freedom Party.[197] The election, conducted amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, saw increased provisions for early and postal voting.[198] Key campaign issues encompassed economic policies, healthcare, social welfare, and the nation's response to the ongoing health crisis.

Luxembourg

[edit]In 2023 Luxembourg general election, the christian democrat CSV party remained the largest party in parliament with 21 seats, having won 29.2% of the vote. The Democratic Party (DP) and the Luxembourg Socialist Workers' Party (LSAP) remained the second and third largest parties in parliament, respectively. The Greens suffered a significant loss by winning just 4 seats compared with 9 in the last election.[199] On 13 November Luc Frieden announced a coalition agreement between the CSV and DP. The new cabinet was sworn in by the Grand Duke and Frieden assumed the office of Prime Minister on 17 November.[200]

Montenegro

[edit]The 2020 Montenegrin parliamentary election resulted in a victory for the opposition parties and the fall from power of the ruling DPS, which had ruled the country since the introduction of the multi-party system in 1990. On 31 August, the leaders of three opposition coalitions, For the Future of Montenegro, Peace is Our Nation and In Black and White, agreed to form an expert government, and to continue to work on the European Union accession process. The period before the election was marked by the high polarization of the electorate. Several corruption scandals of the ruling party triggered 2019 anti-government protests, while a controversial religion law sparked another wave of protests.

In April 2021, a wave of protests, dubbed by its organizers as the Montenegrin Spring,[201][202] or the Montenegrin Response/Montenegrin Answer[203][204][205] was launched in Montenegro against the announced adoption of regulations that will make it easier to acquire Montenegrin citizenship, but also take away the citizenship of some Montenegrin emigrants, which the protesters consider as an "attempt of the government to change the ethnic structure of Montenegro" and against the newly formed technocratic government of Montenegro, which the protesters accuse of being "treacherous" and the "satellite of Serbia".[206]

The 2021 Montenegrin episcopal enthronement protests are a series of violent protests against the installation (enthronement) of Joanikije Mićović of the Serbian Orthodox Church as the Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral that took place at the historic Cetinje Monastery on 5 September 2021. Following the enthronement, by mid-September 2021, divisions within the Krivokapić Cabinet led some of the ruling coalition members such as the Democratic Front and Democratic Montenegro to demand that the government be reconstructed or a snap election be held.[207]

Poland

[edit]Protests

[edit]On 7 August 2020, a protest against the arrest of LGBT activist Margot led to a confrontation with police in central Warsaw and resulted in the arrest of 47 others, some of whom were peacefully protesting and others who were bystanders to the event, dubbed "Polish Stonewall" in an analogy to the 1969 Stonewall riots.

The October–December 2020 Polish protests, commonly known as the Women's Strike (Polish: Strajk Kobiet)[citation needed], are the ongoing anti-government demonstrations and protests in Poland that began on 22 October 2020, in reaction to a ruling of the Constitutional Tribunal, mainly consisting of judges who were appointed by the ruling Law and Justice (Polish: Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) dominated United Right, which tightened the law on abortion in Poland. The ruling made almost all cases of abortion illegal, including those cases in which the foetus had a severe and permanent disability, or an incurable and life-threatening disease.[208][209] It was the biggest protest in the country since the end of the People's Republic during the revolutions of 1989.[210][211]

2024 officeholders

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism in Poland |

|---|

|

Donald Franciszek Tusk[d] (born 22 April 1957) is a Polish politician and historian who has served as the prime minister of Poland since 2023, previously holding the office from 2007 to 2014. From 2014 to 2019 Tusk was President of the European Council, and from 2019 to 2022 he was the president of the European People's Party (EPP). He co-founded the Civic Platform (PO) party in 2001 and has been its longtime leader, first from 2003 to 2014 and again since 2021.

Tusk has been officially involved in Polish politics since 1989, having co-founded multiple political parties, such as the free market–oriented Liberal Democratic Congress party (KLD). He first entered the Sejm in 1991 but lost his seat in 1993. In 1994, the KLD merged with the Democratic Union to form the Freedom Union. In 1997, Tusk was elected to the Senate and became its deputy marshal. In 2001, he co-founded another centre-right liberal conservative party, the PO, and was again elected to the Sejm, becoming its deputy marshal.[212] Tusk stood unsuccessfully for President of Poland in the 2005 election and would also suffer defeat in the 2005 Polish parliamentary election.

Leading the PO to victory at the 2007 parliamentary election, he was appointed prime minister, and scored a second victory in the 2011 election, becoming the first Polish prime minister to be re-elected since the fall of communism in 1989.[213] In 2014, he left Polish politics to accept appointment as president of the European Council. The Civic Platform would lose control of both the presidency and parliament to the rival Law and Justice (PiS) party in the 2015 Polish parliamentary election and 2015 Polish presidential election. Tusk was President of the European Council until 2019; although initially remaining in Brussels as leader of the EPP, he later returned to Polish politics in 2021, becoming leader of the Civic Platform again. In the 2023 election, his Civic Coalition won 157 seats in the Sejm to become the second-largest bloc in the chamber. Following the President-appointed Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki's failure to secure a vote of confidence on 11 December, Tusk was elected by the Sejm to become prime minister for a third time. His cabinet was sworn in on 13 December, ending eight years of government by the PiS party.[214]

Having been the longest-serving prime minister of the Third Republic, Tusk oversaw in his first term the reduction and digitization of the public sector, wishing to present himself as a pragmatic liberal realist and technocrat. In the lead-up to the co-organization by Poland of Euro 2012, he invested strongly in infrastructure, expanding the highway network at the cost of the rail sector. In his second term, various scandals, unfulfilled promises and a cooling of the economy in 2012–2014 as a result of his European debt crisis-related austerity policies led to a drop in public support.[215] In the landscape dominated by the PiS after its electoral victories, as an influential holdout he opposed what he considered its democratic backsliding. Returning to power in 2023, he has focused on improving the rule of law and warming up relations between Poland and the EU. Since then, as PM, Tusk has continued aid to Ukraine after the Russian invasion. In 2024, he surprised the public with his appropriation of right-wing themes, such as opposition to illegal migration, prioritizing border security, going as far as to suspend the right of asylum for those who cross the Belarus–Poland border illegally.[216]

Andrzej Sebastian Duda[e] (born 16 May 1972) is a Polish lawyer and politician who has been the sixth and current president of Poland since 2015. Before becoming president, he served as Member of the Sejm (MP) from 2011 to 2014 and as Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2014 to 2015.

Duda was the presidential candidate for the Law and Justice party (PiS) during the presidential election in May 2015. In the first round of voting, he received 5,179,092 votes – 34.76% of valid votes. In the second round of voting, he received 51.55% of the vote, beating the incumbent president Bronisław Komorowski, who received 48.45% of the vote. On 26 May 2015, Duda resigned his party membership as the president-elect.

On 24 October 2019, he received the official support of PiS ahead of his re-election campaign in 2020. He finished first in the first round and then went on to defeat Rafał Trzaskowski in the runoff with 10,440,648 votes or 51.03% of the vote.[217] Throughout his first and second terms, Duda has largely aligned himself with the right-wing ideologies espoused by PiS and its leader Jarosław Kaczyński. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Duda has played an important role in coordinating international efforts to support Ukraine's military.[218]Portugal

[edit]2021 presidential election

[edit]Portugal's center-right president, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, won a second five-year term with around 61 percent of the vote. In unprecedented circumstances, the 2021 presidential election was held less than two weeks after the Portuguese government had placed the nation under lockdown.[219] The results indicated that André Ventura, a far-right, ultranationalist candidate, received close to 12 percent of the vote, while the socialist candidate, Ana Gomes, received nearly 13 percent of the vote.[220]

2022 legislative election

[edit]The 2022 portuguese legislative elections were called when two far-left parties that had supported Antonio Costa's minority government allied with right-wing parties in October to reject his draft budget for 2022.[221] In the election, contrary to expectations, Portugal's ruling center-left Socialist Party secured an absolute parliamentary majority in the snap general election, giving Antonio Costa a solid new mandate as prime minister.[222] The centre-right Social Democrats finished far behind the Socialist Party, who received roughly 42% of the vote, with less than 30% of the vote.[223] As the third-largest legislative force, the far-right party Chega increased substantially from having just one seat in the previous legislative cycle to at 12. Turnout did surpass the previous year's record low of 49%.[224]

Prime Minister resignation

[edit]On 7 November 2023, Prime Minister António Costa submitted his official resignation which was accepted by the President on the same day.[225] The prime minister's resignation came after Portugal's national police executed searches of Costa's residence and various government ministry buildings. The sweeps were a part of a corruption probe related to lithium mining projects in the north of Portugal in addition to a green hydrogen production mega-project in Sines. President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa decided to dissolve parliament and call new elections on 10 March 2024.[226] Costa's government remains in office in a caretaker capacity until a new government is sworn in following the elections.[227]

Romania

[edit]A political crisis began in Romania on 1 September 2021 engulfing both major coalition partners of the Cîțu Cabinet, namely the conservative-liberal National Liberal Party (PNL) and the progressive-liberal Save Romania Union (USR), then USR PLUS.[228] The crisis was sparked by disagreements over the so-called Anghel Saligny investment program meant to develop Romanian settlements,[229] which was supported by Prime Minister Cîțu but was severely criticized by USR PLUS (referring to it as a "brand new OUG 13 abuse")[230][231] whose ministers boycotted a government meeting.[229] In response, Prime Minister Cîțu sacked Justice Minister Stelian Ion (USR)[232] and named Interior Minister Lucian Bode (PNL) as interim, igniting a crisis.[233][234] In retaliation, USR PLUS submitted a motion of no confidence (also known as a motion of censure) against the Cîțu Cabinet together with the nationalist opposition party Alliance for the Unity of Romanians (AUR)[235][236] and by 7 September, all USR PLUS ministers resigned on their own.[237] Negotiations between PSD, PNL and UDMR for a new majority took place throughout most of November 2021, after which Ciucă was designated again by Iohannis as prime minister on 22 November. The crisis finally ended on 25 November, with the Ciucă Cabinet taking office.

The 2024 Romanian parliamentary election and the 2024–25 Romanian presidential election resulted in uncertainty.[238]

Russia

[edit]President

[edit]

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin[f] (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Russia from 1999 to 2000[g] and again from 2008 to 2012.[h][239] At 25 years and 20 days, he is the longest-serving Russian or Soviet leader since the 30-year tenure of Joseph Stalin.

Putin worked as a KGB foreign intelligence officer for 16 years, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He resigned in 1991 to begin a political career in Saint Petersburg. In 1996, he moved to Moscow to join the administration of President Boris Yeltsin. He briefly served as the director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) and then as secretary of the Security Council of Russia before being appointed prime minister in August 1999. Following Yeltsin's resignation, Putin became acting president and, in less than four months, was elected to his first term as president. He was reelected in 2004. Due to constitutional limitations of two consecutive presidential terms, Putin served as prime minister again from 2008 to 2012 under Dmitry Medvedev. He returned to the presidency in 2012, following an election marked by allegations of fraud and protests, and was reelected in 2018.

During Putin's initial presidential tenure, the Russian economy grew on average by seven percent per year,[240] driven by economic reforms and a fivefold increase in the price of oil and gas.[241][242] Additionally, Putin led Russia in a conflict against Chechen separatists, reestablishing federal control over the region.[243][244] While serving as prime minister under Medvedev, he oversaw a military conflict with Georgia and enacted military and police reforms. In his third presidential term, Russia annexed Crimea and supported a war in eastern Ukraine through several military incursions, resulting in international sanctions and a financial crisis in Russia. He also ordered a military intervention in Syria to support his ally Bashar al-Assad during the Syrian civil war, with the aim of obtaining naval bases in the Eastern Mediterranean.[245][246][247]

In February 2022, during his fourth presidential term, Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which prompted international condemnation and led to expanded sanctions. In September 2022, he announced a partial mobilization and forcibly annexed four Ukrainian oblasts into Russia. In March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin for war crimes[248] related to his alleged criminal responsibility for illegal child abductions during the war.[249] In April 2021, after a referendum, he signed into law constitutional amendments that included one allowing him to run for reelection twice more, potentially extending his presidency to 2036.[250][251] In March 2024, he was reelected to another term.

Under Putin's rule, the Russian political system has been transformed into an authoritarian dictatorship with a personality cult.[252][253][254] His rule has been marked by endemic corruption and widespread human rights violations, including the imprisonment and suppression of political opponents, intimidation and censorship of independent media in Russia, and a lack of free and fair elections.[255][256][257] Russia has consistently received very low scores on Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, The Economist Democracy Index, Freedom House's Freedom in the World index, and the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index.Consolidation of Putin's power

[edit]The entire Russian cabinet resigned in January 2020, with a new Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin soon sworn in.[258] Following this, a constitutional referendum was held in Russia in 2020.[259] The draft amendments to the Constitution were submitted to a referendum in accordance with article 2 of the Law on Amendments to the Constitution.[260] The referendum was criticized for extending the rule of Vladimir Putin, as well as for not following the normal rules for referendums in Russia (by being labelled an "all-Russian vote" instead).[261][262]

The anti-corruption activist and politician Alexei Navalny was the target of an attempted assassination by the Russian Federal Security Service, whose members involved in the attempt he exposed together with the investigative journalism outlet Bellingcat.[263] Following his return to Russia, he was arrested and immediately placed in pre-trial detention.[264] This, and the release of his film A Palace for Putin, led to the 2021 Russian protests. Navalny was ultimately sentenced to two-and-a-half years in a penal colony.[265] A court ordered the Anti-Corruption Foundation, linked to Navalny, to cease its activities.[266]

Repercussions of the invasion of Ukraine

[edit]Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, daily anti-war demonstrations and protests broke out across Russia.[267] The protests have been met with widespread repression by the Russian authorities, with over 8,000 arrests being made[268][269][270] from 24 February to 4 March.[271][272][273] By 27 February, 4,000 scientists and science journalists, 6,200 medics, 5,000 architects and 6,700 artists in Russia had signed electronic petitions against the invasion.[274] On 6 March, the monitoring group OVD-Info reported over 5,000 arrests throughout the day,[275][276] bringing the total number of arrests since the start to over 12,000.

On 26 February 2022, Russia's communications regulator, Roskomnadzor, ordered independent media outlets to take down reports that described the Russian invasion of Ukraine as an "assault, invasion, or declaration of war", otherwise fines and blocks would be issued.[277] From 1 March, Russian schools started war-themed social studies classes for teenagers based on the Russian government's position on history; one teaching manual (publicized by independent media outlet MediaZona) for such classes asserted that "genocide" had been occurring in eastern Ukraine for eight years, and that Russia in this case was responding with a "special peacekeeping operation" in Ukraine, which was "not a war".[278] On 22 February 2023 the monitoring group OVD-Info reported that there was almost 20,000 arrests due to anti-war position and protests.[279] Also by 15 April 2023 they report that in Russia there are 528 being persecuted under criminal law.[280]

Internal power struggles

[edit]On 23 June 2023, the Wagner Group, a Russian government-funded paramilitary and private military company, staged a rebellion. The rebellion occurred after a period of increasing tensions between the Russian Ministry of Defence and the leader of Wagner, Yevgeny Prigozhin. At least thirteen servicemen of the Russian military were killed during the rebellion. On the rebels' side, several Wagner members were reported injured and two military defectors were killed according to Prigozhin.[281] While Prigozhin was supportive of the Russian invasion of Ukraine,[282] he had previously publicly criticized Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov, blaming them for the country's military shortcomings and accusing them of handing over "Russian territories" to Ukraine.[283] Prigozhin portrayed the rebellion as a response to an alleged attack on his forces by the ministry, and demanded that Shoigu and Gerasimov be turned over to him.[284] In a televised address on 24 June, Russian president Vladimir Putin denounced Wagner's actions as treason and pledged to quell the rebellion.

Prigozhin's forces took control of Rostov-on-Don and the headquarters of the Southern Military District in the city. An armored column of Wagner troops advanced through Voronezh Oblast towards Moscow. Armed with mobile anti-aircraft systems, the rebels repelled the air attacks of the Russian military, whose actions did not deter the progress of the column. Ground defenses were concentrated on the approach to Moscow. Before Wagner reached the defenses, Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko brokered a settlement with Prigozhin, who agreed to end the rebellion. On the late evening of 24 June, Wagner forces turned around, and those that had remained in Rostov-on-Don began withdrawing. As per the agreement, the Federal Security Service, which had initiated a case for armed rebellion under Article 279 of the Criminal Code closed the case on 27 June 2023, dropping the charges.

An Embraer Legacy 600 crashed near Kuzhenkino in Tver Oblast, approximately 100 kilometres north of its departure point in Moscow, on 25 August 2023. Among the ten victims were Yevgeny Prigozhin and Dmitry Utkin, key figures associated with the Wagner Group, a Russian state-funded private military company.[285][286][287][288] The circumstances of the crash led to widespread speculation and numerous theories, with many pointing to political motivations and possible involvement of powerful entities in Russia. While official Russian sources downplayed the incident, many observers, including international leaders, implied or openly suggested that the crash was a politically motivated assassination.

Serbia

[edit]On 7 July 2020, a series of protests and riots began over the government announcement of the reimplementation of the curfew and the government's allegedly poor handling of the COVID-19 situation, as well as being a partial continuation of the "One of Five Million" movement. The initial demand of the protesters had been to cancel the planned reintroduction of curfew in Serbia during July, which was successfully achieved in less than 48 hours of the protest.[289] Among other causes, the protests were driven by the crisis of democratic institutions under Aleksandar Vučić's rule and the growing concern that the President is concentrating all powers in his hands at the expense of the parliament.[290]

Slovakia

[edit]In the 2023 Slovak parliamentary election, the left-wing populist, social conservative and Pro-Russia, Smer-SD (Direction – Social Democracy), led by former Prime Minister Robert Fico, emerged as the largest party, winning 42 seats. The social-liberal and pro-European, PS (Progressive Slovakia) came in second, with 32 seats. Former Prime Minister Peter Pellegrini's social-democratic, Hlas-SD (Voice – Social Democracy), which split from Smer-SD in 2020, came in third with 27 seats, making Pellegrini the kingmaker in government formation negotiations.[291] On 11 October, Smer-SD, Hlas-SD, and ultranationalist SNS ratified their coalition agreement, according to which they were to receive 6, 7, and 3 ministerial portfolios, respectively.[292]

Slovenia

[edit]A series of protests broke out after the formation of Janez Janša's government in early 2020, with protestors demanding Janša's resignation and early elections.[293] Janša was accused of eroding freedom of media since assuming office. According to a report by International Press Institute Slovenia experienced a swift downturn in media and press freedom. IPI accused Janša of creating a hostile environment for journalists by his tweets, which IPI described as "vitriolic attacks".[294][295] He was also accused of usurping power and corruption and compared to Viktor Orbán.[296][297] In the 2022 Slovenian parliamentary election, the Freedom Movement led by Robert Golob won 41 seats in its first election. It had campaigned on a transition to green energy, an open society and the rule of law. It won the highest number of seats for a single party in the elections since the independence of Slovenia.

Spain

[edit]Premierships

[edit]

The premiership of Pedro Sánchez began when Sánchez was sworn in as Prime Minister of Spain by King Felipe VI on 2 June 2018 and is currently ongoing.[298] He is the first prime minister in the recent Spanish history to reach the premiership after succeeding in a vote of no confidence against a ruling prime minister.[299][300] He was also the first prime minister elected by Parliament without being a member of parliament.[299]

During his speech as alternative candidate in the vote of no confidence, he said he planned to form a government that would eventually dissolve the Cortes Generales and call for a general election, but he did not specify when he would do it[301] while also saying that before calling for an election he intended take a series of measures like increasing unemployment benefits and proposing a law of equal pay between the sexes.[302] However, he also said he would uphold the 2018 budget made by the Rajoy government, a condition the Basque Nationalist Party imposed to vote for the motion of no-confidence.[303] Eventually, Sánchez was forced to resign when Parliament rejected the 2019 budget bill[304] and he called for snap election.[305]

After two general elections, in January 2020 Sánchez reached an agreement with the far-left Unidas Podemos electoral alliance,[306] forming Spain's first coalition government since the Second Republic (1931–1939).[307] On 7 October 2020, Sanchez presented a financial plan for the remainder of his term in office that went beyond drafting a new budget and predicted the creation of 800,000 jobs over the next three years.[308] He did not manage to finish his term, as he resigned again after the bad electoral results of the May 2023 local and regional elections, and asked the King to dissolve Parliament.[309] Following the general election on 23 July 2023, Sánchez once again formed a coalition government, this time with Sumar (successors of Unidas Podemos).[310]

Sánchez's premiership has been marked by several international events that have harmed Spanish interests, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the fall of Kabul, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the political instability in Latin America and the conflict between Hamas and Israel, among others. At the same time, domestic events such as the Storm Filomena and the Cumbre Vieja volcanic eruption has also caused trouble to his premiership. In any case, Sánchez's policies have had a markedly pro-European character,[311] and the prime minister's economic policy has been characterized by an increase in public spending and taxes, as well as direct opposition to the austerity policy carried out during the 2008–2014 Spanish financial crisis. Equality has been one of the most important elements, having promoted new laws against sexual assaults, an expansion of the abortion law and the approval of the trans law. In this sense, Sánchez has always maintained a balanced cabinet of men and women.[312][313][314]

Sánchez's premiership has been one of continuous confrontations with the opposition, which has harshly criticized criticized for his pacts with regional parties, mainly of pro-independence or nationalist ideology.[315][316][317][318] These criticisms increased with the formation of his third government, since measures such as an amnesty law for Catalan independentists condemned by the 2017 illegal independence referendum caused numerous protests in the streets.[319][320][321]Sweden

[edit]A government crisis started on 21 June 2021 in Sweden after the Riksdag ousted Prime Minister Stefan Löfven with a no-confidence vote.[322][323] This was the first time in Swedish history a Prime Minister was ousted by a no-confidence vote.[324][325] Löfven was narrowly re-elected to stay in power later.[326] In November, the Riksdag voted for Social Democrat leader Magdalena Andersson to become the first female prime minister of Sweden. However, Andersson resigned several hours later, after the Green Party quit the coalition because the opposition budget was approved by the Riksdag.[327][328] Andersson took office several days later after a confirmation vote in the Riksdag.[329]

The 2022 Swedish general election saw Andersson's government lose its majority, with the Sweden Democrats becoming the second-largest party.[330] Overall the right-leaning bloc won a majority of seats, with Moderate Party leader Ulf Kristersson widely expected to become prime minister.[331]

Ukraine

[edit]

On 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which had started in 2014. The invasion, the largest and deadliest conflict in Europe since World War II,[332][333][334] has caused hundreds of thousands of military casualties and tens of thousands of Ukrainian civilian casualties. As of 2024, Russian troops occupy about 20% of Ukraine. From a population of 41 million, about 8 million Ukrainians had been internally displaced and more than 8.2 million had fled the country by April 2023, creating Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II.