2013 FQ28

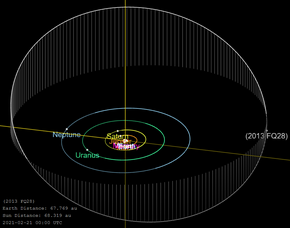

Orbit of 2013 FQ28 | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | CTIO |

| Discovery site | CTIO (first observed only) |

| Discovery date | 17 March 2013 |

| Designations | |

| 2013 FQ28 | |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| Epoch 27 April 2019 (JD 2458600.5) | |

Uncertainty parameter

| |

| Observation arc | 2.09 yr (764 d) |

| Aphelion | 80.096 AU |

| Perihelion | 45.801 AU |

| 62.948 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.2724 |

| 499.44 yr (182,422 d) | |

| 92.132° | |

| 0° 0m 7.2s / day | |

| Inclination | 25.705° |

| 214.89° | |

| 229.51° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 24.49[8] | |

| 6.0[1][2] | |

2013 FQ28 is a trans-Neptunian object, both considered a scattered and detached object, located in the outermost region of the Solar System. It was first observed on 17 March 2013, by a team of astronomers at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. It orbits the Sun in a moderate inclined, moderate-eccentricity orbit. The weak dwarf planet candidate measures approximately 260 kilometers (160 miles) in diameter.

Orbit and classification

[edit]

2013 FQ28 orbits the Sun at a distance of 45.8–80.1 AU once every 499 years and 5 months (182,422 days; semi-major axis of 62.95 AU). Its orbit has an eccentricity of 0.27 and an inclination of 26° with respect to the ecliptic.[2]

With an orbital period of 499 years, and similar to 2015 FJ345, it seems to be a resonant trans-Neptunian objects in a 1:3 resonance with Neptune,[6]: 12 as several other objects,[5] but with a lower eccentricity (0.27 instead of more than 0.60) and a higher perihelia (at 45.8 AU rather than 31–41 AU).

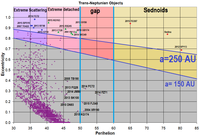

Considered both a scattered and detached object,[3][4][5] 2013 FQ28 is particularly unusual as it has a relatively circular orbit for a scattered-disc object (SDO). Although it is thought that typical SDOs have been ejected into their current orbits by gravitational interactions with Neptune, the low eccentricity of its orbit and the distance of its perihelion (SDOs generally have highly eccentric orbits and perihelia less than 38 AU) seems hard to reconcile with such celestial mechanics. This has led to some uncertainty as to the current theoretical understanding of the outer Solar System. The theories include close stellar passages, unseen planet/rogue planets/planetary embryos in the early Kuiper belt, and resonance interaction with an outward-migrating Neptune. The Kozai mechanism is capable of transferring orbital eccentricity to a higher inclination.[9]

Physical characteristics

[edit]A survey for objects beyond the Kuiper Cliff by Scott Sheppard, Chadwick Trujillo and David Tholen gives a diameter of 250 kilometers assuming a moderate albedo of 0.10.[6] Johnston's archive estimates a diameter of 280 kilometers based on an assumed albedo of 0.09, while American astronomer Michael Brown, calculates a diameter of 266 kilometers, using an estimated albedo of 0.08 and an absolute magnitude of 6.3.[5][7] This is approximately half the size of 2005 TB190, which is estimated at 500 kilometres (310 mi), roughly a quarter the size of Pluto.

On his website, Brown lists this object as a "possible" dwarf planet (200–400 km), which is the category with the lowest certainty in his 5-class taxonomic system.[7] As of 2018, no spectral type and color indices, nor a rotational lightcurve have been obtained from spectroscopic and photometric observations. The body's color, rotation period, pole and shape remain unknown.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "2013 FQ28". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2013 FQ28)" (2015-04-20 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ a b Jewitt, David, Morbidelli, Alessandro, & Rauer, Heike. (2007). Trans-Neptunian Objects and Comets: Saas-Fee Advanced Course 35. Swiss Society for Astrophysics and Astronomy. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-71957-1.

- ^ a b Lykawka, Patryk Sofia; Mukai, Tadashi (July 2007). "Dynamical classification of trans-neptunian objects: Probing their origin, evolution, and interrelation". Icarus. 189 (1): 213–232. Bibcode:2007Icar..189..213L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.01.001. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnston, Wm. Robert (7 October 2018). "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d Sheppard, Scott S.; Trujillo, Chadwick; Tholen, David J. (July 2016). "Beyond the Kuiper Belt Edge: New High Perihelion Trans-Neptunian Objects with Moderate Semimajor Axes and Eccentricities". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 825 (1): 7. arXiv:1606.02294. Bibcode:2016ApJ...825L..13S. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/825/1/L13. S2CID 118630570.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Michael E. "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system?". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ "2013 FQ28 – Ephemerides". AstDyS-2, Asteroids – Dynamic Site, Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Allen, R. L.; Gladman, B.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Petit, J.-M.; Parker, J. W.; Nicholson, P. (March 2006). "Discovery of a Low-Eccentricity, High-Inclination Kuiper Belt Object at 58 AU". The Astrophysical Journal. 640 (1): L83 – L86. arXiv:astro-ph/0512430. Bibcode:2006ApJ...640L..83A. doi:10.1086/503098. S2CID 15588453. (Discovery paper)

External links

[edit]- List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects, Minor Planet Center

- Discovery Circumstances: Numbered Minor Planets (1)–(5000) – Minor Planet Center

- List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects, Johnston's Archive

- 2013 FQ28 at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 2013 FQ28 at the JPL Small-Body Database