1944 Jamaica hurricane

Surface weather analysis conducted by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project of the storm near peak intensity approaching Jamaica on August 20 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 16, 1944 |

| Dissipated | August 24, 1944 |

| Category 3 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | ≤973 mbar (hPa); ≤28.73 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 116 direct |

| Areas affected | Windward Islands, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Mexico (Yucatán Peninsula and Veracruz), Texas |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1944 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1944 Jamaica hurricane was a deadly major hurricane that swept across the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico in August 1944. Conservative estimates placed the storm's death toll at 116. The storm was already well-developed when it was first noted passing westward over the Windward Islands into the Caribbean Sea on August 16. A ship near Grenada with 74 occupants was lost, constituting a majority of the deaths associated with the storm. The following day, the storm intensified into a hurricane, reaching its peak strength on August 20 with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). At this intensity, the major hurricane made landfall on Jamaica later that day, traversing the length of the island. The damage wrought was extensive, with the strong winds destroying 90 percent of banana trees and 41 percent of coconut trees in Jamaica; the overall damage toll was estimated at "several millions of dollars". The northern coast of Jamaica saw the most severe damage, with widespread structural damage and numerous homes destroyed across several parishes. In Port Maria, the storm was considered the worst since 1903.

Land interaction weakened the hurricane, and the storm maintained this lessened intensity as it passed the Cayman Islands, producing measured gusts of 80–90 mph (130–140 km/h). On August 22, the hurricane moved ashore the Yucatán Peninsula near Cozumel and eventually emerged into the Bay of Campeche as a tropical storm. On August 24, the storm made landfall for a final time near Tampico, Mexico, bringing with it heavy rains that caused flooding throughout the coasts of Veracruz and Texas, killing 12. The storm dissipated over the mountainous terrain of inland Mexico later that day. Heavy rains were reported across the Rio Grande Valley, causing minor flooding. A tornado produced by the storms killed one person in McCook, Texas and injured fifteen others.

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On August 16, 1944, decreased pressures just east of Barbados were indicative of a passing tropical storm.[1][2] The storm's first entry in the official Atlantic hurricane database lists the system as already possessing winds of 50 mph (80 km/h);[3] the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project noted that the possibility that the tropical cyclone forming east of the Lesser Antilles remains ambiguous due to a lack of observations over the open Atlantic. Not long after its first detection, the tropical storm intensified into a hurricane on August 17 as it crossed into the Caribbean Sea near Grenada. Gradual intensification took hold as the storm progressed west-northwestwards across the Caribbean.[2] A ship en route to Buenos Aires, Argentina crossed the eye of the hurricane 180 mi (290 km) south of Puerto Rico the following day, recording a central pressure of 973 mbar (hPa; 28.73 inHg); this was the lowest pressure measured in connection with the storm.[4] On the following day, the small tropical cyclone strengthened into the equivalent of a Category 3 hurricane on the modern Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale, making the storm a major hurricane.[2]

At around 16:00 UTC on August 20, the hurricane made landfall in the vicinity of Boston Bay along the coast of Jamaica with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). At landfall, the hurricane's eye spanned 5 mi (8.0 km) across, resulting in a 15–20 minute lull in winds over eastern portions of Jamaica as the eye passed overhead.[2] The storm traversed the island over several hours, emerging near Montego Bay by 23:00 UTC that day as a weakened system equivalent to a Category 1 hurricane.[2][3] The storm largely maintained its strength in the western Caribbean Sea, passing near Grand Cayman on August 21 with the same intensity with which it departed from Jamaica.[1][3] The following morning, the hurricane struck the Yucatán Peninsula near Cozumel Island and degenerated into a tropical storm over the peninsula. Despite reemerging over the Bay of Campeche, weakening continued; the system ultimately moved ashore near Tuxpan, Mexico as a minimal tropical storm early on August 24 before dissipating inland later that day.[2]

Preparations, impact, and aftermath

[edit]Jamaica

[edit]

On August 19, the United States Weather Bureau issued a hurricane alert for Jamaica and advised precaution to points in the Caribbean west and northwest of the island.[5] Waves began buffeting the Jamaican coast in advance of the storm: a "very heavy" swell was noted along Palisadoes with the center still 70 mi (110 km) away.[2] Early reports, although scant, suggested that the hurricane was one of the most significant in Jamaica's history, with no comparable storm in the preceding two decades.[6] The most powerful effects were felt in the Blue Mountains,[6] resulting in a swath of devastation on the northern shore of Jamaica.[7] The island sustained heavy losses to its banana and coconut crop, with an estimated damage toll of several millions of dollars. An estimated 90 percent of banana trees and 41 percent of coconut trees were lost.[1] These crops were primarily located in the parishes of Clarendon, Portland, Saint Thomas, Saint Catherine, and Trelawny, as well as in the Montego Bay valley.[7] Within the core coconut-producing region between Saint Thomas and Saint Ann, 30 percent of coconuts were either blown down or destroyed.[8] Entire coconut plantations were denuded by the strong winds.[1] Heavy rains caused the reservoir at Hermitage Dam to overflow—the reservoir's water level was initially 53 ft (16 m) below the spillway. The 10.88 in (276 mm) of rainfall measured in the dam's watershed was a record for the area.[9]

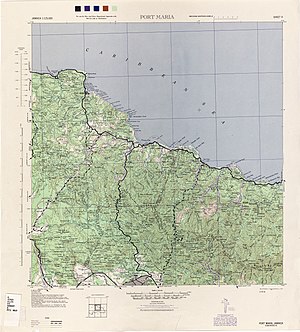

In total, over 30 fatalities occurred in Jamaica, primarily as a result of the hurricane's strong winds. The severest damage was inflicted upon Portland, Saint Ann, and Saint Mary parishes.[2] Five people were killed and many others reportedly injured in Saint Mary Parish.[10] Numerous homes were destroyed in the parish, leaving hundreds of people displaced.[11] In the parish's capital town of Port Maria, nearly all buildings sustained damage and hundreds of people including infants and schoolchildren required immediate assistance;[10][7] a hospital was destroyed in nearby Annotto Bay,[10] injuring 40 people.[7] The Daily Gleaner called the hurricane Port Maria's worst storm since 1903, as an estimated 75 percent of buildings in the town were at least heavily damaged. The parish's church sustained significant damage, with both of its transepts unroofed and clergy house destroyed.[12] The overturning of two 14.5 long tons (14.7 t) railway cars in Annotto Bay suggested that winds reached 100–120 mph (160–190 km/h) there.[2] A copra factory in the adjacent communities of Frontier and Wentworth was also badly damaged.[12]

At least six people were killed in Saint Ann Parish. Most homes located on the parish waterfront were destroyed. In Saint Ann's Bay, the court house and parish church all sustained heavy damage. Sugar stores and factories in the town were damaged.[13] Port Antonio in Portland Parish was heavily damaged by the hurricane—nearly all buildings were damaged, with most flattened and others unroofed.[7] Several public buildings, including the city's town hall and court house, were either damaged or destroyed.[14] A five-ward poorhouse was destroyed and several schools lost their roofs.[7] Two people were killed in the port by flying debris.[12] All telecommunication lines were downed in Port Antonio and electricity and transportation service was hampered.[14] Virtually all homes in Buff Bay were damaged, and three churches were destroyed. Ninety-five percent of coconut trees in the settlement were blown down, as well as local banana and breadfruit plantations. Many other communities in Portland Parish suffered similar effects, reporting the destruction of most of their buildings;[7] thousands were left homeless.[14] The Member of Parliament for the parish, H. E. Allen, conservatively estimated the number of homeless persons at 6,000, along with the complete loss of the banana industry and significant loss to coconut trees.[15] Three people were killed and several others injured in Skibo, with considerable losses to livestock reported throughout the parish.[7] At Famouth in Trelawny Parish, the Rose Hall Sugar Factory lost its chimney, and a police station 2 mi (3.2 km) away was destroyed; 500–600 people were rendered homeless in the parish. Other communities in Trelawny reported numerous destroyed homes and an 80–100 percent loss of bananas.[16] Small houses were destroyed and a girls' school severely damaged in Montego Bay in Saint James Parish by 60 mph (97 km/h) winds, with the storm's severest effects lasting for roughly two hours. One indirect death was reported in the city.[17]

Winds in the capital city of Kingston topped out at 60 mph (97 km/h).[1] Damage to buildings in the capital city was relatively minor,[18] though transportation and electrical service was disrupted. Fallen trees and fencing tore wires and laid across tramways and streets. Flooding rivers exacerbated the traffic disruptions, submerging or destroying bridges across several parishes.[7] Communications between Kingston and the rest of Jamaica were also severed.[19] Elsewhere in Saint Andrew Parish, widespread crop and infrastructure damage occurred in Swains Spring, Coopers Hill, and Padmore.[7] At Spanish Town in Saint Catherine Parish, trees were uprooted and communications lost between the town and Kingston. While businesses there otherwise avoided significant impacts, their roofs were damaged.[20] Most homes and plantations were destroyed in districts in western Saint Andrew Parish, displacing hundreds of people.[21]

Following the storm, The Daily Gleaner initiated a relief fund to aid in the storm's aftermath;[22] the fund was later managed by the Central Council of Voluntary Social Services.[23] On August 22, Governor of Jamaica Sir John Huggins compelled a conference at Hibbert House with all heads of the colony's ministries, establishing a Central Relief Committee to coordinate with local relief operations and serve as the government's principal communications channel vis-à-vis hurricane relief.[24]

Elsewhere

[edit]Across the Caribbean outside of Jamaica, the hurricane's effects were scattered. A British vessel near Grenada with 74 people on board was lost. Gusts of 80–90 mph (130–140 km/h) swept over the Cayman Islands.[1] One station documented a gust of 90 mph (140 km/h) early on August 21.[2] A ship was lost off the Yucatán Peninsula, though information on its crew and effects was unknown. Twelve people were killed in Veracruz as a result of flooding from the hurricane's third and final landfall near Tuxpan.[1][25] Others–their numbers unknown–were missing following a surge of meltwater from Pico de Orizaba triggered by the tropical storm.[25] Communication lines were downed in Tampico, delaying early damage reports.[26]

The U.S. Weather Bureau issued a storm warning for the lower Texas coast from Matagorda Bay to Brownsville, anticipating that the hurricane would eventually make landfall in the Brownsville area. Aircraft stationed at coastal airfields were moved farther inland, and small craft northwards to the Louisiana coast were brought to port.[27] The passing storm brought heavy rains to the Rio Grande Valley, with rainfall totals reaching over 5 in (130 mm) in Brownsville.[28][29] Roma reported 5.1 in (130 mm) on the night of August 22, marking the first rainfall event of that magnitude in nearly a decade. A slightly rain-swollen Rio Grande resulted in minor flooding downstream, disrupting transportation between the United States–Mexico border southward to Monterrey, Mexico.[28] Projections suggested that a few hundred acres of crops in the immediate floodplain would be inundated, with marginal effects elsewhere. Five oil wells in Wilacy County were suspended after the flooding cut off their water supplies.[30] A tornado struck McCook, killing one person and injuring fifteen others; fourteen of the injured were located in a single home. Crop damage was also reported in connection with the tornado.[31]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Sources

- Sumner, H. C. (December 1944). "North Atlantic Hurricanes and Tropical Disturbances of 1944" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 72 (12). Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society: 237–240. Bibcode:1944MWRv...72..237S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1944)072<0237:NAHATD>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Sumner 1944, p. 238.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- ^ a b c "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 11, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ Sumner 1944, p. 240.

- ^ "Hurricane Heads Towards Jamaica; Shipping Warned". Lancaster New Era. Vol. 66, no. 843. Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. August 19, 1944. p. 6. Retrieved July 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Hurricane". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 179. Kingston, Jamaica. August 22, 1944. p. 6 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Northside Hit Hard by Devastating Storm". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 179. Kingston, Jamaica. August 22, 1944. pp. 1, 8 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Death Toll Mounts in Worst Storm Since 1903". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Reservoir Full; Restrictions Lifted". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 179. Kingston, Jamaica. August 22, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c "Five Dead, Many Hurt, Damage of Millions in Jamaica Storm". The Journal. No. 214. Montreal, Quebec. Canadian Press. August 21, 1944. p. 9. Retrieved July 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "2 Killed, Wide Damage in Jamaica Hurricane". The Gazette. Vol. 173, no. 201. Montreal, Quebec. Canadian Press. August 21, 1944. p. 7. Retrieved July 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Death, Damage, and Destruction in St. Mary and Portland". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 179. Kingston, Jamaica. August 22, 1944. pp. 1, 8 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "St. Ann's Bay Shattered; Six Perish in Parish". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b c "Portland's Dismal Story". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. pp. 1, 9 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "M.L.C. for Portland Sees Havoc; 6,000 Estimated Homeless". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Trelawny: Falmouth in Ruins". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. p. 9 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Montego Bay: Heavy Damage". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 179. Kingston, Jamaica. August 22, 1944. p. 8 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Storm Heads Towards Cuba". The Windsor Daily Star. Vol. 52, no. 146. Windsor, Ontario. August 21, 1944. p. 9. Retrieved July 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bananas Hit". Mansfield News-Journal. Vol. 60, no. 168. Mansfield, Ohio. International News Service. August 21, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved July 1, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Spanish Town". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 179. Kingston, Jamaica. August 22, 1944. p. 8 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "St. Andrew Districts Badly Hit". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. p. 9 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Fund Opened For Relief of Island Storm Sufferers". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 179. Kingston, Jamaica. August 22, 1944. pp. 1, 8 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Storm Relief Committee Set Up". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. p. 3 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ "Governor Names Central Storm Relief Committee". The Daily Gleaner. Vol. 110, no. 180. Kingston, Jamaica. August 23, 1944. p. 1 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Plays Out Into Rain". The Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 31, no. 85. Austin, Texas. Associated Press. August 25, 1944. p. 18. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Storm Goes Into Mexico". The Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 73, no. 299. Austin, Texas. United Press. August 24, 1944. p. 8. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gulf Town Under Storm Wraps As Storm Nears". Jefferson City Post-Tribune. Vol. 78, no. 81. Jefferson City, Missouri. United Press. August 22, 1944. p. 5. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Blows Into Mexico As River Mounts". Valley Evening Monitor. No. 47. McAllen, Texas. August 24, 1944. pp. 1–2. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Texas Squalls to Continue; New Hurricane to Strike North of Tampico Tonight". The Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 73, no. 298. Austin, Texas. August 23, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Rio Grande to Flood Waters". The Austin American-Statesman. Vol. 31, no. 86. Austin, Texas. Associated Press. August 26, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "One Killed As Hurricane Shifts Course". The El Paso Drives. No. 237. El Paso, Texas. Associated Press. August 24, 1944. p. 1. Retrieved July 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.