Wirephoto

Belinograph BEP2V wirephoto machine by Édouard Belin, 1930 | |

| Process type | Physical, Analogue |

|---|---|

| Industrial sector(s) | Wire Service, Photojournalism |

| Main technologies or sub-processes | Telegraph, Telephone, Photography |

| Product(s) | Fax, photography |

| Leading companies | Western Union, AT&T, Associated Press, others |

| Year of invention | 1920s |

Wirephoto, telephotography or radiophoto is the sending of photographs by telegraph, telephone or radio.

History

[edit]

Technologically and commercially, the wirephoto was the successor to Ernest A. Hummel's Telediagraph of 1895, which had transmitted electrically scanned shellac-on-foil originals over a dedicated circuit connecting the New York Herald and the Chicago Times Herald, the St. Louis Republic, the Boston Herald, and the Philadelphia Inquirer.[1][2]

Édouard Belin's Bélinographe of 1913, which scanned using a photocell and transmitted over ordinary phone lines, formed the basis for the Wirephoto service. In Europe, services similar to a wirephoto were called a Belino.

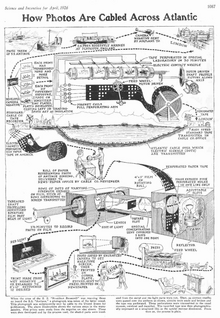

The Bartlane system, invented by Harry G. Bartholomew and Maynard D. McFarlane, was a technique invented in 1920 to transmit digitized newspaper images over submarine cable lines between London and New York.[3] and was first used to transmit a picture across the Atlantic in 1921.[4]

Western Union transmitted its first photograph in 1921. AT&T followed in 1924,[5] and RCA began sending Radiophotos in 1926.[6]

The first wirephoto systems were slow and did not reproduce well. In 1929, Vladimir Zworykin, an electronics engineer working for Western Electric, came up with a system that produced a better reproduction and could transmit a full page in approximately one minute.[7]

In the 1930s, wirephoto machines of any reasonable speed were very large and expensive and required a dedicated phone line. News media firms like Associated Press used expensive leased telephone lines to transmit wirephotos. In the mid-1930s a technology battle began for less expensive portable wirephoto equipment that could transmit photos over standard phone lines.

The Associated Press began its Wirephoto service in 1935 and held a trademark on the term "AP Wirephoto" from 1963 to 2004. The first AP photo sent by wire depicted the December 1934 crash of a small plane in New York's Adirondack Mountains.[8][9]

When the U.S. Navy airship USS ZRS-5 crashed into the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California, the AP Wirephoto transmitted its first drawing — a conceptual sketch by staff artist Noel Sickles of the crash and search for survivors. According to Sickles, the Wirephoto staff initially did not want to transmit the drawing because it was not a photo.[10] The New York Times's Wide World News Photo Service had just installed a prototype photo transmitting machine in San Francisco the day of the crash. A photo was taken of the Macon's survivors when they came ashore and quickly transmitted to New York City over regular phone lines for publication the following morning.[11] By 1936, a wirephoto copier and transmitter that could be carried anywhere and needed only a standard long-distance phone line was put into use by International News Photos.[11]

During the United States's leaflet dropping campaign over the Empire of Japan near the end of World War II, Honolulu would transmit some radiophoto images to Saipan depicting proposed leaflet messages for the printing press on Saipan to produce.[12]

After World War II at haute couture shows in Paris, Frederick L. Milton would sketch runway designs and transmit his sketches via Bélinographe to his subscribers, who could then copy Parisian fashions.[13] In 1955, four major French couturiers (Lanvin, Dior, Patou, and Jacques Fath) sued Milton for piracy, and the case went to the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court.[14] Wirephoto enabled a speed of transmission that the French designers argued damaged their businesses.[15]

See also

[edit]- Frederick Bakewell

- Alexander Bain (inventor)

- Giovanni Caselli

- Fax

- Hellschreiber

- Pantelegraph

- Slow-scan television

References

[edit]- ^ Cook, Charles Emerson (April 1900). "Pictures by Telegraph (HTML transcription)". Pearson's Magazine. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ "From Pearson's Magazine, April 1900 Pictures by Telegraph". Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ "The Bartlane Transmission System". DigicamHistory.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ Rensen, Marius. "The Bartlane System". hffax.de. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ^ "1924: Fax Service". AT&T Labs timeline. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Hotaling, Burton L. (June 1948). "Facsimile Broadcasting: Problems and Possibilities". Journalism Quarterly. 25 (2): 139–144. doi:10.1177/107769904802500204. ISSN 0022-5533. S2CID 67332802.

- ^ "Photo Letters Sent in a Minute by Radio". Popular Science. September 1929. p. 62. Retrieved 2012-04-28 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tramz, Mia (January 1, 2015). "Celebrating 80 Years of Associated Press' Wirephoto". Lightbox. Time. eISSN 2169-1665. ISSN 0040-781X. OCLC 1311479. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015.

The first AP Wirephoto with original caption affixed: 'The wreckage of a small plane lies in a wooded area near Morehousville, N.Y., on Dec. 31, 1934.'

- ^ "AP History 1901-1950: The Modern Cooperative Grows". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2005-04-17. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ^ Canwell, Bruce (2011-10-16). "'Macon' Something of It". The Library of American Comics. Archived from the original on 2015-09-09.

- ^ a b Schnurmacher, Emile C (July 1937). "Wire That Photo". Popular Mechanics. pp. 392–395, 128A – 133A. Retrieved 2012-04-28.

- ^ The Information War in the Pacific, 1945 Paths to Peace, Josette H. Williams.

- ^ Grumbach, Didier (2015). History of international fashion. Northampton, MA: Interlink Publishing Group. pp. 101–3. ISBN 978-1-56656-076-4. OCLC 921187802.

- ^ Nathaus, Klaus (2016-01-22). Made in Europe: The Production of Popular Culture in the Twentieth-Century. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-317-63742-4.

- ^ Goncourt, Edmond de; Goncourt, Jules de (1956). Records and Briefs New York State Appellate Division. New York. p. 136.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

[edit]- "Pictorial Telegraphy," Literary Digest, vol. 10, no. 19 (March 9, 1895), pg. 14.

External links

[edit] Media related to Telephotography at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Telephotography at Wikimedia Commons- 1930s How Photographs Were Transmitted by Wire: Spot News (1937) - CharlieDeanArchives on YouTube