William Willoughby, 5th Baron Willoughby de Eresby

William Willoughby, 5th Baron Willoughby de Eresby | |

|---|---|

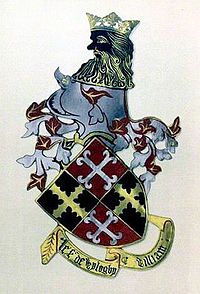

Arms of Sir William de Willoughby, 5th Baron Willoughby d'Eresby, KG | |

| Born | c.1370 |

| Died | 4 December 1409 Newcastle upon Tyne |

| Noble family | Willoughby de Eresby |

| Spouse(s) | Hon. Lucy le Strange Lady Joan Holland |

| Issue | Robert Willoughby, 6th Baron Willoughby de Eresby Sir Thomas Willoughby Elizabeth Willoughby, Baroness Beaumont Margery Willoughby, Baroness FitzHugh Margaret Willoughby, Lady Skipwith |

| Father | Robert Willoughby, 4th Baron Willoughby de Eresby |

| Mother | Alice de Skipwith |

William Willoughby, 5th Baron Willoughby de Eresby KG (c.1370 – 4 December 1409) was an English baron.

Origins

[edit]William Willoughby was the son of Robert Willoughby, 4th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, by his first wife, Alice de Skipwith, daughter of Sir William de Skipwith, Chief Baron of the Exchequer.[2] He had four half-brothers by his father's second wife, Margery la Zouche: Robert, Thomas, John and Brian.[3]

After the death of Margery la Zouche (d. 18 October 1391), his father married thirdly Elizabeth le Latimer (d. 5 November 1395), suo jure 5th Baroness Latimer, daughter of William Latimer, 4th Baron Latimer, and widow of John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby. By this marriage, William had a half-sister, Margaret Willoughby, who died unmarried. By her first marriage Elizabeth Latimer had a son, John Neville, 6th Baron Latimer (c.1382 – 10 December 1430), and a daughter, Elizabeth Neville, who married her step-brother, Sir Thomas Willoughby (died c. 20 August 1417).[4]

Career

[edit]The 4th Baron died on 9 August 1396, and Willoughby inherited the title as 5th Baron. He was given seisin of his lands on 27 September.[5]

Hicks notes that the Willoughby family had a tradition of military service, but that the 5th Baron 'lived during an intermission in foreign war and served principally against the Welsh and northern rebels of Henry IV'.[6] Willoughby joined Bolingbroke, the future King Henry IV, soon after his landing at Ravenspur, was present at the abdication of Richard II in the Tower on 29 September 1399, and was one of the peers who consented to King Richard's imprisonment. In the following year he is said to have taken part in Henry IV's expedition to Scotland.[7]

In 1401 he was admitted to the Order of the Garter, and on 13 October 1402 was among those appointed to negotiate with the Welsh rebel, Owain Glyndŵr. When Henry IV's former allies the Percy Family rebelled in 1403, Willoughby remained loyal to the King. In the July of that year, he was granted lands that had been in the custody of Henry Percy, who had been killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury on 21 July 1403. Willoughby was appointed to the King's council in March 1404. On 21 February 1404 he was among the commissioners appointed to expel aliens from England.[8]

In 1405 Hotspur's father, Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland, again took up arms against the King, joined by Lord Bardolf, and on 27 May Richard Scrope, Archbishop of York, perhaps in conjunction with Northumberland's rebellion, assembled a force of some 8,000 men on Shipton Moor. Scrope was tricked into disbanding his army on 29 May, and he and his allies were arrested. Henry IV denied them trial by their peers, and Willoughby was among the commissioners[9] who sat in judgment on Scrope in his own hall at his manor of Bishopthorpe, some three miles south of York. The Chief Justice, Sir William Gascoigne, refused to participate in such irregular proceedings and to pronounce judgment on a prelate, and it was thus left to the lawyer Sir William Fulthorpe to condemn Scrope to death for treason. Scrope was beheaded under the walls of York before a great crowd on 8 June 1405, 'the first English prelate to suffer judicial execution'.[10] On 12 July 1405 Willoughby was granted lands forfeited by the rebel Earl of Northumberland.[11]

In 1406 Willoughby was again appointed to the Council. On 7 June and 22 December of that year he was among the lords who sealed the settlement of the crown.[12]

Marriages and issue

[edit]Willoughby married twice:

- Firstly, soon after 3 January 1383, Lucy le Strange, daughter of Roger le Strange, 5th Baron Strange of Knockin, by Aline, daughter of Edmund FitzAlan, 9th Earl of Arundel, by whom he had two sons and three daughters:[13]

- Robert Willoughby, 6th Baron Willoughby de Eresby, who married firstly, Elizabeth Montagu, and, secondly, Maud Stanhope.

- Sir Thomas Willoughby, who married Joan Arundel, daughter and co-heiress of Sir Richard Arundel by his wife, Alice. Their descendants, who include Catherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk, inherited the barony. Catherine became the 12th baroness and the title descended through her children by her second husband, Richard Bertie.

- Elizabeth Willoughby, who married Henry Beaumont, 5th Baron Beaumont (d.1413).

- Margery Willoughby, who married William FitzHugh, 4th Baron FitzHugh. Their son, the 5th Baron, would marry Lady Alice Neville, sister of Warwick the Kingmaker. Alice was a grandniece of Willoughby's second wife, Lady Joan Holland. The 5th baron and his wife Alice were great-grandparents to queen consort Catherine Parr.

- Margaret Willoughby, who married Sir Thomas Skipwith.

- Secondly, to Lady Joan Holland (d. 12 April 1434), widow of Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, and daughter of Thomas Holland, 2nd Earl of Kent, by Lady Alice FitzAlan, daughter of Richard FitzAlan, 10th Earl of Arundel, by whom he had no issue.[14] After Willoughby's death his widow married, thirdly, Henry Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Masham, who was beheaded on 5 August 1415 after the discovery of the Southampton Plot on the eve of King Henry V's invasion of France. She married, fourthly, Sir Henry Bromflete, Baron Vessy (d. 16 January 1469).[15]

Death and burial

[edit]

Willoughby died at Edgefield, Norfolk on 4 December 1409 and was buried in the Church of St James in Spilsby, Lincolnshire, with his first wife.[16] A chapel in the church at Spilsby still contains the monuments and brasses of several early members of the Willoughby family, including the 5th baron and his first wife.[17]

Sources

[edit]- Cokayne, George Edward (1936). The Complete Peerage, edited by H.A Doubleday and Lord Howard de Walden. Vol. IX. London: St. Catherine Press.

- Cokayne, G.E. (1959). The Complete Peerage, edited by Geoffrey H. White. Vol. XII (Part II). London: St. Catherine Press.

- Harriss, G.L. (2004). "Willoughby, Robert (III), sixth Baron Willoughby (1385–1452)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50229. Retrieved 5 December 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- Hicks, Michael (2004). "Willoughby family (per. c.1300–1523)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52801. Retrieved 6 December 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- Holmes, George (2004). "Latimer, William, fourth Baron Latimer (1330–1381)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16103. Retrieved 6 December 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- McNiven, Peter (2004). "Scrope, Richard (c.1350–1405)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24964. Retrieved 7 December 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ISBN 1449966373 - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham. Vol. III (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ISBN 144996639X - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham. Vol. IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ISBN 1460992709

References

[edit]- ^ Hope, W. H. St. John, The Stall Plates of the Knights of the Order of the Garter 1348 – 1485: A Series of Ninety Full-Sized Coloured Facsimiles with Descriptive Notes and Historical Introductions, Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company, 1901

- ^ "The complete peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, extant, extinct, or dormant; Vol. 12 Part 2". www.familysearch.org. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, pp. 661–2; Richardson III 2011, pp. 450–2; Richardson IV 2011, pp. 332–3, 422–5; Hicks 2004.

- ^ Cokayne 1936, p. 503; Cokayne 1959, pp. 661–2; Richardson I 2011, p. 333; Richardson III 2011, pp. 242–6; Richardson IV 2011, pp. 332–3; Holmes 2004.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 662; Richardson I 2011, p. 334.

- ^ Hicks 2004.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 662; Richardson I 2011, p. 334.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 662.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 662.

- ^ McNiven 2004.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 662.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, pp. 662–3.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 663; Richardson IV 2011, pp. 334–7.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 663; Richardson IV 2011, p. 334.

- ^ Cokayne 1959, p. 663; Richardson IV 2011, p. 334.

- ^ Richardson IV 2011, p. 334.

- ^ Hicks 2004.