Whatley, Alabama race riot of 1919

| Part of Red Summer | |

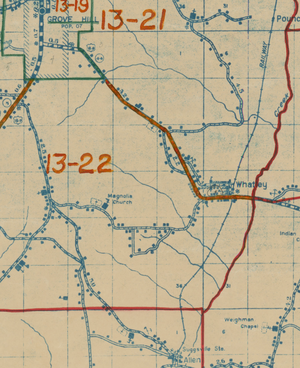

Map of Whatley, Clarke County, Alabama | |

| Date | Friday, August 1, 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Whatley, Alabama, United States |

| Non-fatal injuries | Multiple gunshots |

The Whatley, Alabama race riot of 1919 was a riot, gun battle between the local Black and White community on August 1, 1919.

Background

[edit]From July 27, 1919, to August 3, 1919, there was a Chicago Race Riot that was covered extensively in national media. This increased tension in both the Black and White communities. Also, in July 1919 there were a number of racial incidents in Alabama including a race riot in Tuscaloosa, Alabama and in Hobson City, Alabama the black mayor, Newman O'Neal, faced death threats and was assaulted forcing him to flee.

Race riot

[edit]On August 1, 1919, a fight broke out between a White man and a group of Black youths. The violence quickly spiralled out of control and a gun battle broke out between White and Black communities where two white men and one Black man were shot but not seriously. However on August 2, 1919, a black man by the name of Archie Robinson and another black man were taken from their home and lynched. They are memorialized in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. [1] A few of those wounded were Fred Bates and Charles Chapman who received a bullet in the hip.[2] [3] The Chattanooga News reported that at one point a white mob had surrounded a group of Blacks in the woods.[3] Media reports later said that local Sheriff C. E. Cox, of Clarke County was able to suppress the riot with his police presence.[3]

Alabama Senate

[edit]At the time the Alabama legislature was worried about racial strife and passed a resolution. This resolution says:

Be it resolved by the house of representatives of the state of Alabama, the Senate concurring:

- That the legislature of Alabama views with much concern and anxiety the highly disordered condition of various communities in the north and the middle west, particularly as evidenced by the race riots taking place in the cities of Washington and Chicago, in which there was large loss of human life and property.

- That the apparent hatred which exists between the races in these communities is to be deeply deplored, and the sympathy of the people of the United States Is extended the conservative and law-abiding citizens of those sections, and who are believed to be wholly out of sympathy with such conditions.

- That the people of this state believe that the political and business leaders of these sections ought to be animated by a better spirit of fraternity and high mindedness and fair dealing in their conduct toward the large number of colored people which have migrated into their midst.

- That it is believed that if those leaders and the people of those states generally were prompted more by human considerations and a sense of Justice, which would manifest themselves in a practical way rather than in a course of conduct based on purely idealistic and theoretical conditions a better spirit would prevail.

- That as an example of a nearly ideal approach to cordial and friendly relations, they are referred to the fine spirit of mutual understanding which exists between the races In the south.

-Representative Dickson of Jefferson county[3]

The resolution went to the senate at once and was adopted by that body.

Aftermath

[edit]This uprising was one of several incidents of civil unrest that began in the so-called American Red Summer of 1919. Terrorist attacks on black communities and white oppression in over three dozen cities and counties. In most cases, white mobs attacked African American neighborhoods. In some cases, black community groups resisted the attacks, especially during the Chicago Race Riot and Washington D.C. race riot which killed 38 and 39 people respectively. Most deaths occurred in rural areas during events like the Elaine Race Riot in Arkansas, where an estimated 100 to 240 black people and 5 white people were killed.[4]

See also

[edit]- Chicago Race Riot of 1919

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

Bibliography

[edit]Notes

- ^ The Pensacola Journal 1919, p. 1.

- ^ The News Scimitar 1919, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d The Chattanooga News 1919, p. 10.

- ^ The New York Times 1919.

References

- The Chattanooga News (August 2, 1919). "Quell Alabama Race Riot Solons Praise Amity". The Chattanooga News. Chattanooga, Tennessee: News Pub. Co. pp. 1–14. ISSN 2471-1977. OCLC 12703770. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- The New York Times (October 5, 1919). "For Action on Race Riot Peril". The New York Times. New York, NY. ISSN 1553-8095. OCLC 1645522. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- The News Scimitar (August 2, 1919). "Danger of Race Riot In Alabama Passes". The News Scimitar. Memphis, Tennessee: Gilbert D. Raine. pp. 1–16. ISSN 2473-3199. OCLC 39898320. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- The Pensacola Journal (August 3, 1919). "Sheriff quells grave disorder over shooting". The Pensacola Journal. Pensacola, Florida: Mayes & Co. ISSN 1941-109X. OCLC 16280864. Retrieved August 3, 2019.