Wedgwood

| Industry | Household goods |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1759 |

| Founder | Josiah Wedgwood |

| Headquarters | , England |

| Owner | Fiskars |

| Parent | WWRD Holdings Limited |

| Website | wedgwood |

Wedgwood is an English fine china, porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer that was founded on 1 May 1759[1] by the potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood and was first incorporated in 1895 as Josiah Wedgwood and Sons Ltd.[2] It was rapidly successful and was soon one of the largest manufacturers of Staffordshire pottery, "a firm that has done more to spread the knowledge and enhance the reputation of British ceramic art than any other manufacturer",[3] exporting across Europe as far as Russia, and to the Americas. It was especially successful at producing fine earthenware and stoneware that were accepted as equivalent in quality to porcelain (which Wedgwood only made later), though considerably less expensive.[4]

Wedgwood is especially associated with the "dry-bodied" (unglazed) stoneware Jasperware in contrasting colours, and in particular that in "Wedgwood blue" and white, always much the most popular colours, though there are several others. Jasperware has been made continuously by the firm since 1775, and also much imitated. In the 18th century, however, it was table china in the refined earthenware creamware that represented most of the sales and profits.[5]

In the later 19th century, it returned to being a leader in design and technical innovation, as well as continuing to make many of the older styles. Despite increasing local competition in its export markets, the business continued to flourish in the 19th and early 20th centuries, remaining in the hands of the Wedgwood family, but after World War II it began to contract, along with the rest of the English pottery industry.

After buying a number of other Staffordshire ceramics companies, in 1987 Wedgwood merged with Waterford Crystal to create Waterford Wedgwood plc, an Ireland-based luxury brands group. In 1995 Wedgwood was granted a Royal Warrant from Queen Elizabeth II,[6] and the business was featured in a BBC Four series entitled Handmade by Royal Appointment[7] alongside other Warrant holders Steinway, John Lobb Bootmaker and House of Benney. After a 2009 purchase by KPS Capital Partners, a New York–based private equity firm, the group became known as WWRD Holdings Limited, an initialism for "Waterford Wedgwood Royal Doulton". This was acquired in July 2015 by Fiskars, a Finnish consumer goods company.[8]

Early history

[edit]

Josiah Wedgwood (1730–1795), came from an established family of potters, and trained with his elder brother.[9] He was in partnership with the leading potter, Thomas Whieldon, from 1754 until 1759, when a new green ceramic glaze he had developed encouraged him to start a new business on his own. Relatives leased him the Ivy House in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent,[10] and his marriage to Sarah Wedgwood, a distant cousin with a sizable dowry, helped him launch his new venture.[citation needed]

Wedgwood led "an extensive and systematic programme of experiment",[11] and in 1765 created a new variety of creamware, a fine glazed earthenware, which was the main body used for his tablewares thereafter. After he supplied her with a teaset for twelve the same year, Queen Charlotte gave official permission to call it "Queen's Ware" (from 1767).[12] This new form, perfected as white pearlware (from 1780), sold extremely well across Europe, and to America.[13] It had the additional advantage of being relatively light, saving on transport costs and import tariffs in foreign markets.[14] It caused considerable disruption to the makers of European faience and delftware, then the main European tableware bodies; some went out of business and others adopted English-style bodies themselves.[15]

Wedgwood developed a number of further industrial innovations for his company, notably a way of measuring kiln temperatures accurately, and several new ceramic bodies including the "dry-body" stonewares, "black basalt" (by 1769), caneware and jasperware (1770s), all designed to be sold unglazed, like "biscuit porcelain".[16]

In 1766, Wedgwood bought a large Staffordshire estate, which he renamed Etruria, as both a home and factory site; the Etruria Works factory was producing from 1769, initially making ornamental wares, while the "useful" tablewares were still made in Burslem.[17]

In 1769 Wedgwood established a partnership with Thomas Bentley, who soon moved to London and ran the operations there. Only the "ornamental" wares such as vases are marked "Wedgwood & Bentley" and those so marked are at an extra level of quality. The extensive correspondence between Wedgwood and Bentley, who was from a landowning background, show Wedgwood often relied on his advice on artistic questions. Wedgwood felt the loss keenly when Bentley died in 1780.[18]

Wedgwood's slightly younger friend, William Greatbatch, had followed a similar career path, training with Whieldon and then starting his own firm around 1762. He was a fine modeller, especially of moulds for tablewares, and probably did most of Wedgwood's earlier moulds as an outside contractor. After some twenty years, Greatbatch's firm went under in 1782, and by 1786 he was a Wedgwood employee, continuing for over twenty years until he retired in 1807, on generous terms specified in Wedgwood's will. In the early period he seems also to have acted as agent for Wedgwood on trips to London,[19] and after Wedgwood's retirement he may have in effect managed the Etruria works.[citation needed]

Transfer printing and enamel painting

[edit]

Wedgwood was an early adopter of the English invention of transfer printing, which allowed printed designs, for long only in a single colour, that were far cheaper than hand-painting. Hand-painting was still used, the two techniques often being combined, with painted borders surrounding a printed figure scene. From 1761 wares were shipped to Liverpool for the specialist firm of Sadler and Green to print;[20] later this was done in-house at Stoke.[citation needed]

From 1769 Wedgwood maintained a workshop for overglaze enamel painting by hand in Little Cheyne Row in Chelsea, London,[21] where skilled painters were easier to find. The pieces received a light second firing to fix the enamels in a small muffle kiln; this work was also later moved to Stoke. There was also a showroom and shop in Portland House, 12 Greek Street, Soho, London. Painting included border patterns or bands and relatively straightforward floral motifs on tableware. Complicated figure scenes and landscapes in painted enamels were generally reserved for the most expensive "ornaments" like vases, but transfer printed items had these.[citation needed]

The Frog Service is a large dinner and dessert service made by Wedgwood for Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, and completed in 1774. The service had fifty settings, and 944 pieces were ordered, 680 for the dinner service and 264 for the dessert.[22] Although Wedgwood was already transfer printing many tablewares, this was entirely hand-painted in Chelsea in monochrome, with English views copied from prints and drawings; the final appearance was not dissimilar to transfer printing, but each image was unique. Also at Catherine's request, each piece carries a green frog. Although Wedgwood was paid just over £2,700 he barely made a profit, but milked the prestige of the commission, exhibiting the service in his London showroom before delivery.[23]

Jasperware

[edit]Wedgwood's best known product is Jasperware, created to look like ancient Roman cameo glass, itself imitating cameo gems. The most popular jasperware colour has always been "Wedgwood blue" (a darker shade is sometimes called "Portland Blue"), an innovation that required experiments with more than 3,000 samples. In recognition of the importance of his pyrometric beads, Josiah Wedgwood was elected a member of the Royal Society in 1783. In recent years, the Wedgwood Prestige collection continued to sell replicas of the original designs, as well as modern neo-classical style jasperware.[citation needed]

The main Wedgwood motifs in jasperware, and the other dry-bodied stonewares, were decorative designs that were highly influenced by the ancient cultures being studied and rediscovered at that time, especially as Great Britain was expanding its empire. Many motifs were taken from ancient mythologies: Roman, Greek and Egyptian. Meanwhile, archaeological fever caught the imagination of many artists. Nothing could have been more suitable to satisfy this huge business demand than to produce replicas of ancient artefacts. From 1787 to 1794 Wedgwood even ran a studio in Rome, where young Neoclassical artists were in abundance, producing wax models for reliefs, often to designs sent from England. The most famous design is Wedgwood's copy of the Portland Vase, a famous Roman vase now in the British Museum, which was lent to Wedgwood to copy.[citation needed]

Other dry-bodied stonewares

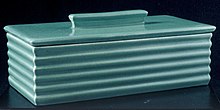

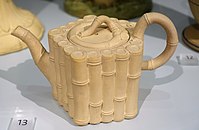

[edit]Wedgwood developed other dry-bodied stonewares, meaning that they were sold unglazed. The first of these was what he called "basaltes", now more often "black basalt ware" or just basalt ware, perfected by 1769. This was a tough body in solid black, much used for classical revival styles.[24] Wedgwood developed an attractive reddish stoneware he called rosso antico ("ancient red") This was often combined with black basalt.[25] This was followed by caneware or bamboo ware, the same colour as bamboo and often modelled to look as though objects were made of the plant; first introduced in 1770, but mostly used between 1785 and 1810.[26]

-

Cauliflower coffee-pot, with Wedgwood's green lead glaze, c. 1760, Thomas Whieldon and Josiah Wedgwood

-

Tea caddy, c. 1770, transfer printed by Sadler and Green.

-

Caneware teapot, 1779-1780

-

Jasperware teacup, c. 1784

Figures

[edit]

Generally Wedgwood avoided the typical type of Staffordshire figures, white earthenware standing figurines of people or animals that by about 1770 were usually brightly painted, though sometimes sold in plain glazed white. These imitated rather successfully the porcelain figures pioneered by Meissen porcelain, a style which by about 1770 was being produced by the majority of porcelain factories, on the continent and in Britain. Though Staffordshire figures fell precipitously in price and quality after about 1820, in the 18th century many were still well-modelled and carefully painted.[citation needed]

Instead Wedgwood concentrated on more sculptural figures, and produced many busts or small relief portrait plaques of celebrities, both types of high quality. The subjects were generally notably serious: politicians and royalty, famous scientists and writers. Many were small, with the oval shape usual in the painted portrait miniature; others were larger. They were probably generally intended for framing; many examples still retain their frames.[citation needed]

Many subjects reflected Wedgwood's religious and political views, Unitarian and somewhat Radical respectively,[27] in particular what is probably the best-known Wedgwood relief, the abolitionist design Am I Not a Man and a Brother?, the basic design of which is usually credited to Wedgwood, although others drew and sculpted the final versions. This appeared in many formats in print and pottery from about 1786, and was very widely distributed, often given away.[28]

In addition plaques of varying sizes, most in jasperware, caught the fashion for Neoclassicism, with a great variety of classical subjects, but mostly avoiding nudity. The smaller ones were intended to be set in jewellery, sometimes in steel by Matthew Boulton's factory, and larger sizes might be framed for hanging, or inset in architectural features like fireplace mantels, mouldings and furniture. Smallest of all were many button designs.[citation needed]

-

Voltaire in black basalt, modelled by Anthony Keeling, c. 1779. One of relatively few standing figures.

-

Relief portrait plaque of Joseph Priestley by Giuseppe Ceracchi, plaque 10.5 x 8.2 cm; 4¼" x 3¼"

-

Large vase, c. 1775, Wedgwood & Bentley. Earthenware with paint effects and gilding, both now partly worn away.

-

Volute Krater Vase, c. 1780, using a variety of techniques to imitate ancient Athenian red-figure vase painting

-

Belt clasp designed by Lady Templeton and Emma Crewe,[29] 1780-1800, the setting perhaps by Matthew Boulton.

After Josiah

[edit]

The firm lost some momentum after the deaths of Bentley in 1780 and the retirement of Josiah Wedgwood in 1790 (he died in 1795). By 1800 it had about 300 employees in Staffordshire. The Napoleonic Wars made exporting to Europe impossible for long periods, and left export markets in disarray. Thomas Byerley, Josiah's nephew, became a partner and was mainly in charge for some years, as Josiah's sons John, known as Jack, and Josiah II ("Joss"), who joined the firm only on Josiah I's retirement, had developed other interests, in particular horticulture. After Waterloo in 1815, there was a dramatic drop in the vital exports to America. Byerley's death in 1810 forced the brothers to confront the reality of the financial situation, as they needed to buy out his widow. Between the partners and other debtors, the firm was owed some £67,000, a huge sum. Joss bought Jack out, and continued as sole owner.[30]

Wedgwood continued to grow under Jack and his son Francis Wedgwood, and by 1859 the factory had 445 employees. As well as updated versions of wares from the previous century, bathroom ceramics such as sinks and lavatories had been important in recent decades, and Wedgwood's reputation for technical and design innovation had sunk considerably. However, they did introduce porcelain (see below), lustre ware by 1810, a form of Parian ware they called "Carrara" in 1848, and a "Stone China" from about 1827, the last of which was not especially successful. Neoclassicism was now less fashionable, and one response was to add floral enamels to black basalt wares from around 1805. Godfrey Wedgwood, Josiah I's great-grandson became a partner in 1859, and had considerable success reviving the firm in both these areas,[31] in what was generally a successful period for British pottery.[citation needed]

Porcelain

[edit]

Wedgwood's first decades of success came from producing wares that looked very like porcelain, and had broadly the same qualities, though not quite as tough, nor as translucent. During Josiah's lifetime and some time afterwards Wedgwood did not make porcelain itself. European factories had increasing success with porcelain, both soft-paste in England and France, and hard-paste mostly in Germany, which were still competing with Japanese and Chinese export porcelain, which were very popular, though expensive, in Europe. Towards the end of the 18th century other Staffordshire manufacturers introduced bone china as an alternative to translucent and delicate Chinese porcelain.[32]

By 1811 Byerley, as manager of the London shop, wrote back to Stoke that "Every day we are asked for China Tea Ware—our sales of it would be immense if we had any—Earthenware Teaware is quite out of fashion...", and in response in 1812 Wedgwood first produced their own bone china, with hand-painting.[33][34] However West End taste did not perhaps represent all of Wedgwood's markets, and it was not the huge commercial success promised, and after thinking of doing so in 1814, the firm finally stopped making it in 1822. But when revived in 1878 it eventually became an important part of production.[35]

- 19th century

-

Empire Style jasperware tripod vase, c. 1805

-

Black basalt teapot with Chinese Flowers, c. 1820

-

Silver lustreware teapot, early 19th century

-

"Portland blue" jasperware, c. 1840

-

Victorian majolica dish and cover (for cheese?), c. 1880

Artists who worked with Wedgwood

[edit]

From very early on Josiah Wedgwood was determined to maintain high artistic standards, which was an important part of his efforts to appeal to the top end of the market with pottery rather than porcelain wares. He relied considerably on Bentley in London in this, as is clear from their correspondence. As with other potteries, the designs of prints were very often copied.[citation needed]

- William Hackwood worked for Wedgwood from 1769 until 1832, starting at around 13, but after some years becoming the main modeller in the factory, finishing and making the moulds for the designs of others, and sculpting his own.[36]

- John Flaxman (Junior), then 19 years old but already a trained sculptor exhibiting at the Royal Academy, was employed as a modeller and designer from 1775, mainly of reliefs in both cases. He worked for the next 12 years mostly for Wedgwood, staying in London and sending modellos in wax on pieces of slate or glass to Stoke. The "Dancing Hours" may be his most well known design. His father, John Flaxman Senior, made and sold plaster casts in a shop in London, and was supplying Wedgwood with some by 1770.[37]

- Aristocratic ladies who produced designs, many in a softer "Romantic" version of Neoclassical style, were Lady Elizabeth Templetown, Emma Crewe and Lady Diana Beauclerk; these were also mostly for jasperware reliefs.[38]

- Henry Webber, a trained sculptor, was employed at Etruria in 1782, after being recommended by Sir William Chambers and Sir Joshua Reynolds, becoming chief sculptor in 1785, a position he held until 1806.[39] He worked on the replica Portland Vase, and with Flaxman and "Jack" (Josiah II) was sent to Italy on a Grand Tour for the young man, and also to look at establishing a modelling studio in Rome, which was set up by Webber in 1788. Flaxman, remaining in Rome as an independent artist, agreed to supervise it part-time.[40]

- George Stubbs was not employed by Wedgwood, but late in his career developed an interest in painting in enamels, and persuaded Wedgwood to make new, large plaques for him to use. His paintings on these were not successful at the time, but are now very highly regarded.[citation needed]

- Giuseppe Ceracchi, an Italian sculptor, in England 1773–1781.[citation needed]

- William Blake worked on engraving for Wedgwood's china catalogues in 1815.[41]

- Emile Lessore came to England in 1858 as an established ceramic painter and after a few months at Mintons he joined Wedgwood. His speciality was enamel paintings, mostly landscapes, on plaques, which fetched very high prices. He and his family did not like living in Staffordshire and in 1867 he returned to France, but Wedgwood continued to use him, sending blanks to be returned for firing, until his death in 1876. Two of his granddaughters, Therese Lessore and Louise Powell, later painted for the firm.[42]

- Daisy Makeig-Jones joined Wedgwood as an apprentice painter in 1909, and in 1915 her "Fairyland Lustre" range launched. This was very popular on both sides of the Atlantic until the Great Depression; it is now keenly collected.[43]

- In the 1930s Keith Murray designed in a broadly Art Deco style.[citation needed]

- Eric Ravilious designed a number of popular pieces such as mugs from 1936 until World War II (during which he died).[citation needed]

- Jasper Conran, who first designed for Wedgwood in 2001, was one of two artistic directors in 2019.[citation needed]

-

Vases designed by Courtney Lindsay, mixing printed and painted decoration, 1900–01

-

Plate in the "Fairyland" lustreware range, designed by Daisy Makeig-Jones, 1915–30

-

One of the animal figures designed by John Skeaping, early 20th century

-

Eric Ravilious, Wedgwood alphabet cup, designed 1937

-

Modern Wedgwood Kutani Crane pattern, in bone china

Ownership

[edit]

Wedgwood family

[edit]Josiah Wedgwood was also a patriarch of the Darwin–Wedgwood family. Many of his descendants were closely involved in the management of the company down to the time of the merger with the Waterford Company:

- John Wedgwood, eldest son of Josiah I, was a partner in the firm from 1790 to 1793 and again from 1800 to 1812.[citation needed]

- Josiah Wedgwood II or "Jack" (1769–1843), second son of Josiah I, succeeded his father as proprietor in 1795 and introduced the production by the Wedgwood company of bone china. [citation needed]

- Josiah Wedgwood III (1795–1880), son of Josiah II, was a partner in the firm from 1825 until he retired in 1842.[citation needed]

- Francis Wedgwood, son of Josiah II, was a partner in the firm from 1827 and sole proprietor following his father's death until joined by his own sons. Financial difficulties caused him to offer for sale soon after taking over the firm its factory at Etruria and the family home Etruria Hall, but only the hall was sold. He continued as senior partner until his retirement to Barlaston Hall in 1876.[citation needed]

- Godfrey Wedgwood (1833–1905), son of Francis Wedgwood, was a partner in the firm from 1859 to 1891. He and his brothers were responsible for the reintroduction of bone china in 1878.[citation needed]

- Clement Wedgwood (1840–1889), son of Francis Wedgwood, was a partner.[citation needed]

- Laurence Wedgwood (1844–1913), son of Francis Wedgwood, was a partner.[citation needed]

- Major Cecil Wedgwood DSO (1863–1916), son of Godfrey Wedgwood, partner from 1884, first Mayor of the federated County Borough of Stoke-on-Trent (1910–1911), was chairman and managing director of Wedgwood until his death in battle in 1916.[citation needed]

- Kennard Laurence Wedgwood (1873–1949), son of Laurence Wedgwood, was a partner. In 1906 he went to the United States and set up the firm's New York office, which became Josiah Wedgwood and Sons USA, an incorporated subsidiary, in 1919.[citation needed]

- Francis Hamilton Wedgwood (1867–1930), eldest son of Clement Wedgwood, was chairman and managing director from 1916 until his sudden death in 1930.[citation needed]

- Josiah Wedgwood V (1899–1968), grandson of Clement Wedgwood and son of Josiah Wedgwood, 1st Baron Wedgwood, was managing director of the firm from 1930 until 1968 and credited with turning the company's fortunes around. He was responsible for the enlightened decision to move production to a modern purpose-built factory in a rural setting at Barlaston. It was designed by Keith Murray in 1936 and built with the assistance of Norman Wilson (father of the writer A. N. Wilson) between 1938 and 1940.[44] He was succeeded as managing director by Arthur Bryan (later Sir Arthur), who was the first non-member of the Wedgwood family to run the firm,[citation needed] and also by Wilson. Bryan persuaded the Wedgwood family to float the company on the London Stock Exchange in 1967, a decision that Wilson opposed.[45]

- Other "Wedgwood" pottery

Ralph Wedgwood, presumably a cousin, made high quality wares in Burslem from c. 1790 until probably 1796, marked "Wedgwood & Co", a name never used by the main firm. He then joined William Tomlinson & Co., a firm in Yorkshire, who promptly dropped their own name, using "Wedgwood & Co" until he left in 1801. That name was revived by Enoch Wedgwood (1813–1879), a distant cousin of the first Josiah, who used Wedgwood & Co, starting in 1860.[46] It was taken over by Josiah Wedgwood & Sons in 1980.[citation needed]

Other potters used blatantly misleading marks: "Wedgewood", "Vedgwood", "J Wedg Wood", all on inferior wares.[47]

1960s and 1970s consolidation

[edit]In 1968, Wedgwood purchased many other Staffordshire potteries including Mason's Ironstone, Johnson Brothers, Royal Tuscan, William Adams & Sons, J. & G. Meakin and Crown Staffordshire. In 1979, Wedgwood purchased the Franciscan Ceramics division of Interpace in the United States. The Los Angeles plant closed in 1984 and production of the Franciscan brand was moved to Johnson Brothers in Britain. In 1986, Waterford Glass Group plc purchased Wedgwood plc, forming the company Waterford Wedgwood plc.[citation needed]

Waterford Wedgwood

[edit]

In 1986, Waterford Glass Group plc purchased Wedgwood plc for US$360 million, with Wedgwood delivering a US$38.7 million profit in 1998 (while Waterford itself lost $28.9 million), after which the group was renamed Waterford Wedgwood plc. From early 1987 to early 1989, the CEO was Patrick Byrne, previously of Ford, who then became CEO of the whole group. During this time, he sold off non-core businesses and reduced the range of Wedgwood patterns from over 400 to around 240. In the late 1990s, the CEO was Brian Patterson. From 1 January 2001, the Deputy CEO was Tony O'Reilly, Junior, who was appointed CEO in November of the same year and resigned in September 2005. He was succeeded by the then-president of Wedgwood USA, Moira Gavin, up until the company went into administration in January 2009.[citation needed]

In 2001, Wedgwood launched a collaboration with designer Jasper Conran, which started with a white fine bone china collection then expanded to include seven patterns. In March 2009, KPS Capital Partners acquired the Waterford Wedgwood group assets. Assets including Wedgwood, Waterford and Royal Doulton were placed into WWRD Holdings Limited.[citation needed]

WWRD Holdings Limited

[edit]On 5 January 2009, following years of financial problems at group level, and after a failed share placement during the 2007–2008 financial crisis, Waterford Wedgwood was placed into administration[48] on a "going concern" basis, with 1,800 employees remaining. On 27 February 2009, Waterford Wedgwood's receiver Deloitte announced that the New York–based private equity firm KPS Capital Partners had purchased certain Irish and UK assets of Waterford Wedgwood, and the assets of its Irish and UK subsidiaries.[49] KPS Capital Partners placed Wedgwood into a group of companies known as WWRD, an abbreviation for "Waterford Wedgwood Royal Doulton".[citation needed]

In 1995 Royal Doulton commissioned a new factory just outside Jakarta, Indonesia.[50] From 2006 to 2008, Wedgwood began to offshore most production to Indonesia to reduce costs, while Waterford production moved to Eastern Europe.[51][52] By 2009 the Jakarta factory employed 1,500 persons producing bone china under both Wedgwood and Royal Doulton brands. Annual production was reported to be 5 to 7 million pieces.[53] In order to reduce costs the majority of production of both brands has been transferred to Indonesia, with only a small number of high-end products continuing to be made in the UK. [54][55]

In May 2015, Fiskars, a Finnish maker of home products, agreed to buy 100% of the holdings of WWRD.[56] On 2 July 2015, the acquisition of WWRD by Fiskars was completed, including the brands Waterford, Wedgwood, Royal Doulton, Royal Albert and Rogaška. The acquisition was approved by the US antitrust authorities.[57]

In 2015 there were complaints of misleading labelling, in that products made in the company's Indonesian factory were sold labelled "Wedgwood England".[58]

Wedgwood Museums and the Museum Trust

[edit]

Wedgwood's founder wrote as early as 1774 that he wished he had preserved samples of all the company's works, and he began to do so. The first formal museum was opened in May 1906, with a curator named Isaac Cook, at the main (Etruria) works. The contents of the museum were stored for the duration of the Second World War and relaunched in a gallery at the new Barlaston factory in 1952. A new purpose-built visitor centre and museum was built in Barlaston in 1975 and remodelled in 1985, with pieces displayed near items from the old factory works in cabinets of similar period. A video theatre was added and a new gift shop, as well as an expanded demonstration area, where visitors could watch pottery being made. A further renovation costing £4.5 million was carried out in 2000, including access to the main factory itself.[citation needed]

Adjacent to the museum and visitor centre are a restaurant and tea room, serving on Wedgwood ware. The museum, managed by a dedicated trust, closed in 2000 and on 24 October 2008, it reopened in a new multimillion-pound building.[citation needed]

In June 2009, the Wedgwood Museum won a UK Art Fund Prize for Museums and Art Galleries for its displays of Wedgwood pottery, skills, designs and artefacts.[59] In May 2011, the archive of the museum was inscribed in UNESCO's UK Memory of the World Register.[60][61][62]

The collection with 80,000 works of art, ceramics, manuscripts, letters and photographs faced being sold off to help satisfy pension debts inherited when Waterford Wedgwood plc went into receivership in 2009. The Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund, various trusts and businesses contributed donations to purchase the collection.[63] On 1 December 2014, the collection was purchased and donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum. The collection will continue to be on display at the Wedgwood Museum on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum.[64]

Minton Archive

[edit]The Minton Archive comprises papers and drawings of the designs, manufacture and production of the defunct pottery company Mintons. It was acquired by Waterford Wedgwood in 2005 along with other assets of the Royal Doulton group.[65] In the event, the Archive was presented by the Art Fund to the City of Stoke-on-Trent, but it was envisaged that some material would be displayed at Barlaston as well as the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.[66]

Wedgwood station

[edit]Wedgwood railway station was opened in 1940 to serve the Wedgwood complex in Barlaston.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Pottery firm marks 250th birthday". BBC. 1 May 2005. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ "History of Josiah Wedgwood & Sons Ltd". potteryhistories.com. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Godden (1992), 337

- ^ Gooden (1992), 337–338; Dawson, 202–203; Hughes, 308–311

- ^ Godden (1992), 337–339

- ^ "Fiskars UK Limited – Wedgwood | Royal Warrant Holders Association". members.royalwarrant.org. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "BBC Four – Handmade: By Royal Appointment, Wedgwood". BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ "Fiskars Corporation has completed the acquisition of WWRD and extended its portfolio with iconic luxury home and lifestyle brands". Press Releases. Fiskars Corporation. 2 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ Dawson, 200; Hughes, 308

- ^ Godden (1992), 337; Hughes, 310

- ^ Dawson, 202

- ^ Dolan, 158–164, 168–169

- ^ Dawson, 202–203; Godden (1992), 337, 340

- ^ Godden (1992), 337

- ^ Godden (1992), 337–338

- ^ Dawson, 202–203

- ^ Godden (1992), 337

- ^ Godden (1992), 338; Young, 12–13 – it is Wedgwood's letters that survive essentially complete, with few of Bentley's.

- ^ Dolan, 82–83, 101, 129

- ^ Hughes, 296

- ^ Dawson, 204

- ^ Mikhail B. Piotrovsky (2000). Treasures of Catherine the Great. Harry N. Abrams. p. 184.

- ^ "Plate", Curator's comments, British Museum; "Wedgwood, frogs and a hedgehog…", The Gardens Trust, 2014; Dawson, 204

- ^ Godden (1992), xix

- ^ Hughes, 54–55

- ^ Godden (1992), xxi

- ^ Though the term "Radical" seems to post-date his death.

- ^ "British History – Abolition of the Slave Trade 1807". BBC. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

The Wedgwood medallion was the most famous image of a black person in all of 18th-century art.

- ^ "Belt Clasp with a Female Making a Sacrifice". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Dolan, 385–389

- ^ Dolan, 389–390; Godden (1992), 339–340

- ^ Dolan, 275–276, 387

- ^ Godden (1992), 339

- ^ The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, ed. Campbell, OUP 2006, Volume 2, p547

- ^ Godden (1992), 339–340; Hughes, 310–311; Dolan, 275–276, 387

- ^ Wedgwood Museum: Hackwood's legacy

- ^ "John Flaxman snr (1726–95)", Wedgwood Museum

- ^ Young, 32, 41, 55

- ^ "Henry Webber (1754–1826)". The Wedgwood Museum. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ Dolan, 352–353; Young, 55

- ^ Michael Davis, William Blake: A New Kind of Man, University of California Press, 1977, pages 140–141

- ^ Godden (1992), 340–341

- ^ Godden (1992), 341

- ^ bibleofbritishtaste. "A.N. Wilson's Wedgwood". Bible of British Taste. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – Wedgwood: A Very British Tragedy". BBC. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ Godden (1992), 334

- ^ Godden (1992), 334

- ^ "Wedgwood goes into administration". BBC. 5 January 2009.

- ^ "Waterford Wedgwood bought by US equity firm KPS Capital". The Irish Times. 27 February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ "Doulton PT – Company Profile and News". Bloomberg News.

- ^ "Indonesia Company Move | AP Archive". aparchive.com. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Morgan, Tom (5 January 2009). "The Sad Legacy of Wedgwood". The Independent. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ "High hopes for Wedgwood in Jakarta". 19 January 2009.

- ^ "Waterford Wedgwood shifts to Asia to save company". 31 December 2008.

- ^ "The sad legacy of Wedgwood". The Independent. London. 5 January 2009.

- ^ Bray, Chad (11 May 2015). "Fiskars Agrees to Buy Owner of Waterford and Wedgwood". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ "Fiskars Corporation has completed the acquisition of WWRD and extended its portfolio with iconic luxury home and lifestyle brands". NASDQ Global News Wire (Press release). 2 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ John Murray Brown, "UK ceramics industry in battle over heritage", Financial Times, 17 May 2015

- ^ "Wedgwood wins £100,000 art prize". BBC. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ "2011 UK Memory of the World Register", United Kingdom National Commission for UNESCO, 2011. Accessed 4 June 2011.

- ^ "Wedgwood Museum archive recognised by UNESCO," Wedgwood Museum. Accessed 4 June 2011.

- ^ "Unesco recognises Wedgwood Museum archive collection", BBC, 24 May 2011. Accessed 4 June 2011.

- ^ "Wedgwood collection 'saved for nation'". BBC. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Loan of Wedgwood Collection to Barlaston finalised". Save the Wedgwood Collection. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Art Fund helps save the Minton Archive for the nation" (PDF). Art Fund. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ "Minton Archive saved for the nation" (Press release).

References

[edit]- Dawson, Aileen, "The Growth of the Staffordshire Ceramic Industry", in: Freestone, Ian, Gaimster, David R. M. (eds), Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions, 1997, British Museum Publications, ISBN 071411782X

- Dolan, Brian, Josiah Wedgwood: Entrepreneur to the Enlightenment, 2004, HarperCollins (UK title, used here), aka Wedgwood: The First Tycoon (US title, page numbers 2 higher), 2004, Viking

- Godden, Geoffrey (1992), An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of British Pottery and Porcelain, 1992, Magna Books, ISBN 1 85422 333 X

- Godden, Geoffrey (1885), English China, 1985, Barrie & Jenkins, ISBN 0091583004

- Hughes, G Bernard, The Country Life Pocket Book of China, 1965, Country Life Ltd

- Young, Hilary (ed.), The Genius of Wedgwood (exhibition catalogue), 1995, Victoria and Albert Museum, ISBN 185177159X

Further reading

[edit]- Burton, Anthony. Josiah Wedgwood: A New Biography (2020)

- Hunt, Tristram. The Radical Potter: Josiah Wedgwood and the Transformation of Britain. Penguin, 2021.

- Langton, John. "The ecological theory of bureaucracy: The case of Josiah Wedgwood and the British pottery industry." Administrative Science Quarterly (1984): 330–354.

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood and the Commercialization of the Potteries", in: McKendrick, Neil; Brewer, John & Plumb, J.H. (1982), The Birth of a Consumer Society: The commercialization of Eighteenth-century England

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood and Factory Discipline." Historical Journal 4.1 (1961): 30–55. online

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood and cost accounting in the Industrial Revolution." Economic History Review 23.1 (1970): 45–67. online

- McKendrick, Neil. "Josiah Wedgwood: an eighteenth-century entrepreneur in salesmanship and marketing techniques." Economic History Review 12.3 (1960): 408–433. online

- Meteyard, Eliza. Life and Works of Wedgwood (2 vol 1865) vol 1 online; also vol 2 online

- Reilly, Robin, Josiah Wedgwood 1730–1795 (1992), a major scholarly biography

External links

[edit]- British porcelain

- Ceramics manufacturers of England

- Companies based in Staffordshire

- Companies based in Stoke-on-Trent

- English brands

- English pottery

- Neoclassicism

- Staffordshire pottery

- Tony O'Reilly family

- Waterford Wedgwood

- Wedgwood pottery

- British companies established in 1759

- 1759 establishments in England

- Fiskars

![Belt clasp designed by Lady Templeton and Emma Crewe,[29] 1780-1800, the setting perhaps by Matthew Boulton.](http://up.wiki.x.io/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Crew_-_Belt_Clasp_with_a_Female_Making_a_Sacrifice_-_Walters_481770.jpg/134px-Crew_-_Belt_Clasp_with_a_Female_Making_a_Sacrifice_-_Walters_481770.jpg)