Wallace Smith (illustrator)

Wallace Smith (December 30, 1888 - January 31, 1937)[1] was an American book illustrator, comic artist, reporter, author, and screenwriter.

Biography

[edit]Born in Chicago in 1888, Smith became Washington correspondent for the Chicago American at the age of 20, remaining with that newspaper for over a decade. According to the book The Madhouse on Madison Street,[2] Smith was "one of the most colorful reporters who ever worked for the Hearst papers," and was born with the last name of Schmidt, which he changed to Smith during World War I.

He was sent to Mexico and did illustrated reporting on several campaigns of Pancho Villa against the Carranza regime.[3] In 1920 he originated the Joe Blow comic panel feature for the Chicago American.[4] In 1921-22 he was assigned to California to cover the Roscoe Arbuckle trials and the William Desmond Taylor murder case.[5] The articles bylined by Smith (for the Chicago American) and Eddie Doherty (for the Chicago Tribune) were so inflammatory that Under-Sheriff Eugene W. Biscailuz, fearing for their safety, offered to provide them each with a bodyguard, but they both declined.[6] In 1923–1924 he contributed with his illustrations (using the nickname "Vulgus") for The Chicago Literary Times, a magazine done in the format and style of a tabloid scandal sheet, cofounded by Ben Hecht and Maxwell Bodenheim with whom he previously collaborated illustrating their books.

Smith moved to Hollywood embarking on successful, decade-long, screenplay-writing career. His services were in high demand - he wrote or contributed to twenty-six screenplays, often enhancing them with detailed scene sketches. Smith's film work included screen adaptations of his novels The Captain Hates the Sea and The Gay Desperado and also Two Arabian Knights, The Lost Squadron, Friends and Lovers.[7]

In 1935, Smith's novel Bessie Cotter about a prostitute's life on the streets of Chicago was judged indecent in England and the publisher fined the equivalent of $1,000. It was published a year earlier in the United States.

He died of a heart attack in his home in Hollywood on January 31, 1937, and was survived by his wife, Echo Smith.[1] His archival papers are at the University of Oregon.[8] The papers include Smith's manuscripts and published pieces, minor correspondence, drawings and illustrations, photographs, and miscellaneous documents.

Fantazius Mallare censorship and illustration art

[edit]

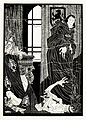

Returning to Chicago, Smith provided the illustrations for Ben Hecht's controversial novel Fantazius Mallare: a Mysterious Oath, which resulted in a $1,000 fine for obscenity in U.S. District Court for both Hecht and Smith.[9] A novel of decadence and mystic existentialism, Fantazius Mallare is a story of a mad recluse—a genius sculptor and painter who is at war with reason. Rather than commit suicide, his doting madness dictates that he must revolt against all evidence of life that exists outside himself. He destroys all of his work and then seeks out a woman who will devote herself to his Omnipotence. What follows is a glorious trek into a horrifying enlightening insanity.

"Neither Hecht nor Smith were much known outside Chicago when they teamed up to produce a book that got them international attention. It was Fantazius Mallare, a weird story of a mad man and it was illustrated in full page line drawings that were as fantastic as the story. There is no question that the book was filled with strong writing and stronger pictures, but the strength sometimes ran to the kind that comes from the cesspool. Frankness pranced straight into vulgarity, at times and that got the boys into a jam with the postal authorities. About 1,000 copies that were in the mails were seized and Hecht and Smith had to stand trial. Both were fined."[10]

"Smith was said by Ronald Clyne to have gone to jail for the Mallare artwork, but apparently this was an exaggeration - he and Hecht were, however, fined $1000 each for "obscenity"; and $1000 was quite a lot of money in 1924. The particular points it is curious about where were the rest of the Wallace Smith artwork - he could hardly have developed that style in the handful of drawings that have been published; and what happened to the copies of Fantazius Mallare seized by the US government - the book did not seem to be as scarce as would have been expected if they had seized even half of the 2000-copy edition. MacAdams was able to answer this last question to some extent - after the obscenity conviction, the publisher made another 2000 copies and sold them "under the counter."

Hecht and Smith went to a great deal of trouble to have themselves convicted of obscenity. They had wanted to create a test case of the federal obscenity law and have a show trial in order to turn public opinion against it by ridicule. Hecht also intended to enter a million-dollar civil suit for defamation of character against John S. Sumner and his infamous New York Society for the Suppression of Vice if Sumner attacked his book. The famous Clarence Darrow was to have been their attorney. The plan was to send review copies of Fantazius Mallare to all of the literary lights of the time, and then have Darrow call these people as expert witnesses at the trial. Alas, the scheme foundered on the unforeseen pusillanimity of the literary establishment - only H. L. Mencken agreed to appear as a witness. In the end there was no trial because Hecht and Smith entered a plea of nolo contendere. The character Fantazius Mallare is said to be a sort of Hecht alter-ego - he appears again in the sequel, The Kingdom of Evil (illustrated by the much inferior artist Anthony Angarola), and in 1935 Hecht wrote and directed a film, The Scoundrel, in which Noel Coward plays Mallare."[11]

In 1926, after moving to Hollywood from Chicago, he presented the silent film star Rod La Rocque with a copy of Fantazius Mallare, a decadent novel written by Ben Hecht, Smith's friend and fellow newspaperman at the Chicago Daily News. But Smith knew Hecht as a decadent novelist, and he knew Fantazius Mallare especially well because he had illustrated Hecht's depraved tale with ten fantastic, Beardleyesque drawings, several of them depicting the sterile orgies of the novel's deluded, reclusive hero. Rod La Rocque must have meant a lot to Wallace Smith, as the inscription he wrote to the star implies: "For Rod La Rocque -who has a thousand masks for his face -but, thank Christ, never an one for his heart." As further token of his admiration, Smith hand-colored a number of the drawings in the book he gave to the celebrated screen idol.[12]

-

Fantazius Mallare - Second Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Third Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Fourth Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Fifth Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Sixth Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Seventh Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Eighth Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Ninth Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Tenth Drawing

-

Fantazius Mallare - Book Cover

At this time he also did illustrations for other books, designed book jackets, frontispieces and end papers. In 1923 he illustrated The Florentine Dagger by Ben Hecht, and frontispieces for Blackguard by Maxwell Bodenheim and The Shining Pyramid by Arthur Machen.

-

Florentine Dagger Cover

-

Florentine Dagger Frontispiece

-

Florentine Dagger - First Drawing

-

Florentine Dagger - Second Drawing

-

Florentine Dagger - Third Drawing

-

Blackguard Cover design

-

Blackguard Frontispiece

-

The Shining Pyramid Book Cover

His early 1920s illustrations show Smith's extraordinary pen skills. Dark and obscure, expressionist and linear, dominated by large black fields they reveal influences of later heritage of Beardsley and Harry Clarke at same time his very distinguishable character.

During his assignments in Mexico, Smith closely observed the peasants for whom Pancho Villa waged war. In his 1923 book, The Little Tigress: Tales Out of the Dust of Mexico, he wrote sympathetically about their plight and brought them to life in his trademark stark black-and-white drawings. In the next few years he wrote short stories published in a variety of magazines including Liberty, The American Magazine, and Blue Book Magazine.[13]

Pendleton Round-Up Poster

[edit]

He was the author of the illustration for the Pendleton Round-Up Association. Round-Up organizers paid Smith $250 for the drawing, copyrighted it in 1925, and began using it as the event's logo. There's no estimating how many times since then the image has been reproduced or seen. Many decades later, the picture still symbolizes at a glance the essence of rodeo competition. The story behind the image is, in 1924, a young talented author and artist, Wallace Smith, asked for and received permission to gain access to the arena during the rodeo for the purpose of making sketches of bucking horses. After three busy days working in the arena and sitting on the north arena fence, he came up with his answer to the thought of creating a bucking horse that would properly symbolize the round up's slogan, "LET 'ER BUCK". The life of that vivid frontispiece of his Oregon Sketches had pleased the bronco-busters so much that they have adopted it as the official poster of the annual Pendleton Round-Up.

In Oregon Sketches Wallace Smith gives glimpses of the new and glorified West, a West that is a revival of all that tradition has contributed to the term, including cowboys and Indians, guns and war paint… As a picture of some of the swiftly changing phases of the West the book is of value.

Works

[edit]Wallace illustrated or published the following:

- Smith, Ed W. Knockouts I have Seen, 1922, Chicago (The Smith-Spinner Publishing Co.)

- Hecht, Ben. Fantazius Mallare: a Mysterious Oath, 1922, Chicago (Covici-McGee)

- Hecht, Ben. The Florentine Dagger: A Novel for Amateur Detectives, 1923, New York (Boni and Liveright)

- DeCasseres, Benjamin. The Shadow Eater, 1923, New York (American Library Service)

- Bodenheim, Maxwell. Blackguard, 1923, Chicago (Covici-McGee)

- Machen, Arthur. The Shining Pyramid, 1923, Chicago (Covici-McGee)

- Smith, Wallace. The Little Tigress: Tales Out of the Dust of Mexico, 1923, New York (Putnam)

- Smith, Wallace. On the Trail in Yellowstone, 1924, New York (Putnam)

- Smith, Wallace. Oregon Sketches, 1925, New York/London (Putnam)

- Smith, Wallace. Are You Decent?', 1927 New York/London (Putnam)

- Smith, Wallace. Tiger's Mate, 1928, New York (Putnam)

- Smith, Wallace. The Captain Hates the Sea, 1933, New York (Covici-Fried)

- Smith, Wallace. Bessie Cotter, 1934, New York (Covici-Fried)

- Smith, Wallace. La Cucaracha: The Story of a Flute Player in Pancho Villa's Band, 1935, article for Collier's Weekly.

- Smith, Wallace. The Happy Alienist: a Viennese Caprice,1936, New York (Harrison Smith and Robert Haas)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Wallace Smith, Author and Artist, Taken by Death", Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, California, pp. B1, February 1, 1937

- ^ Murray, George (1965). The Madhouse on Madison Street. Chicago: Follett Publishing Co. pp. 150–151.

- ^ Ergenbright, Eric L. (October 1934), "Caballero y Soldado", New Movie Magazine: 105

- ^

The Fourth Estate: 12, May 29, 1920

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^

The Fourth Estate: 19, February 18, 1922

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Doherty, Edward (1941). Gall and Honey: The Story of a Newspaperman. New York: Sheed and Ward. p. 200.

- ^ IMDB, retrieved 26 November 2013

- ^ Guide to the Wallace Smith Papers, retrieved 26 November 2013

- ^ "Variety", Variety: 11, February 7, 1924

- ^ The Milwaukee Journal, January 10, 1947, p. 27

- ^ It Goes On The Shelf, October 9, 1992

- ^ Weir, David (2008), Decadent Culture in the United States, SUNY Press, p. 191, ISBN 9780791479179

- ^ The FictionMags Index, retrieved 26 November 2013

External links

[edit]- Fantazius Mallare: A Mysterious Oath book at Archive.

- The Florentine Dagger: A Novel for Amateur Detectives at Archive.

- Blackguard book at Archive.

- Ben Hecht, Wallace Smith, and Fantazius Mallare, by Jerry D. Meyer, April 2010.

- Wallace Smith at IMDb

- Wallace Smith archive at Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon

- 1937 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- American male novelists

- American male screenwriters

- American illustrators

- American male journalists

- 1888 births

- American male short story writers

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters