User:Notropis procne/sandbox6

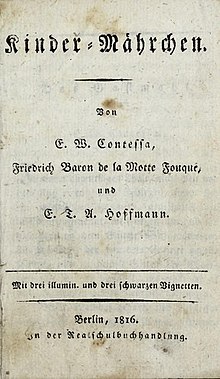

"The Nutcracker and the Mouse King" (German: Nussknacker und Mausekönig) is a novella–fairy tale written in 1816 by Prussian author E. T. A. Hoffmann, in which young Marie Stahlbaum's favorite Christmas toy, the Nutcracker, comes alive and, after defeating the evil Mouse King in battle, whisks her away to a magical kingdom populated by dolls. The story was originally published in Berlin in German as part of the collection Kinder-Märchen, Children's Stories, by In der Realschulbuchhandlung. In 1892, the Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and choreographers Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov turned Alexandre Dumas' adaptation of the story into the ballet The Nutcracker.

Summary

[edit]On Christmas Eve, at the Stahlbaum house, Marie and her siblings receive several gifts. Their godfather Drosselmeyer, a clockmaker and inventor, gifts them a clockwork castle with mechanical people moving around inside. However, the children quickly tire of it. Marie notices a nutcracker, and asks who he belongs to. Her father says that he belongs to all of them, but since Marie is so fond of him, she will be his special caretaker. The siblings pass him amongst themselves, cracking nuts, until Marie's brother Fritz tries to crack one that is too big and hard, and the nutcracker's jaw breaks. Marie, upset, bandages him with a ribbon from her dress.

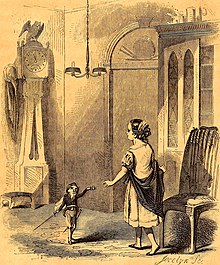

When it is time for bed, the children put their Christmas gifts away in the cabinet where they keep their toys. Marie begs to stay with the nutcracker a while longer and is allowed to do so. She tells him that Drosselmeyer will fix his jaw. At this, his face seems to come alive, and she is frightened, but decides it was her imagination.

The grandfather clock begins to chime, and Marie believes that she sees Drosselmeyer sitting on top of it, preventing it from striking. Mice begin to come out from beneath the floorboards, including the seven-headed Mouse King. The dolls in the toy cabinet come alive, the nutcracker taking command and leading them into battle after putting Marie's ribbon on. The dolls are overwhelmed by the mice. Marie, seeing the nutcracker about to be taken prisoner, throws her slipper at the Mouse King. She then faints into the toy cabinet's glass door, cutting her arm badly.

Marie wakes up in her bed the next morning with her arm bandaged and tries to tell her parents what happened the previous night, but they do not believe her. Days later, Drosselmeyer arrives with the nutcracker, whose jaw has been fixed, and tells Marie the story of Princess Pirlipat and Madam Mouserinks, known as the Queen of the Mice, which explains how nutcrackers came to be and why they look the way they do.

Madam Mouserinks tricked Pirlipat's mother into allowing her and her children to gobble up the lard that was supposed to go into the sausage that the King was to eat at dinner. The King, enraged at Madam Mouserinks for spoiling his supper and upsetting his wife, had his court inventor, Drosselmeyer, create traps for the Mouse Queen and her children.

Madam Mouserinks, angered at the death of her children, swore that she would take revenge on Pirlipat. Pirlipat's mother surrounded her with cats which were supposed to be kept awake by being constantly stroked. The nurses who did so fell asleep, however, and Madam Mouserinks magically turned Pirlipat ugly, giving her a huge head, a wide grinning mouth, and a cottony beard like a nutcracker. The King blamed Drosselmeyer and gave him four weeks to find a cure. He went to his friend, the court astrologer.

They read Pirlipat's horoscope and told the King the only way to cure her was to have her eat the nut Crackatook (Krakatuk), which must be cracked and handed to her by a man who had never been shaved nor worn boots since birth. He must, without opening his eyes, hand her the kernel and take seven steps backwards without stumbling. The King sent Drosselmeyer and the astrologer out to look for both.

The two men journeyed for years without finding either the nut or the man. They then returned home to Nuremberg and found the nut with Drosselmeyer's cousin, a puppet-maker. His son turned out to be the young man needed to crack the Crackatook. The King promised Pirlipat's hand to whoever could crack the nut. Many men broke their teeth on it before Drosselmeyer's nephew cracked it easily and handed it to Pirlipat, who swallowed it and became beautiful again. But Drosselmeyer's nephew, on his seventh backward step, stepped on Madam Mouserinks and stumbled. The curse fell on him, making him a nutcracker. Pirlipat, seeing how ugly he had become, refused to marry him and banished him from the castle.

Marie, while she recuperates from her wound, hears the Mouse King, son of the deceased Madam Mouserinks, whispering in the middle of the night, threatening to bite the nutcracker to pieces unless she gives him her sweets and dolls. She sacrifices them, but he wants more and more. Finally, the nutcracker says that if she gets him a sword, he will kill the Mouse King. Fritz gives her the one from his toy hussars. The next night, the nutcracker visits Marie's room bearing the Mouse King's seven crowns, and takes her to the doll kingdom. She falls asleep in the nutcracker's palace and is brought home. She tries to tell her mother what happened, but again she is not believed, even when she shows her parents the seven crowns, and is forbidden to speak of her "dreams" anymore.

Marie sits in front of the cabinet one day while Drosselmeyer is repairing one of her father's clocks. Marie swears to the Nutcracker that if he were ever really real, she would never behave as Pirlipat did, and would love him whatever he looked like. Then, there is a bang and she faints, falling off the chair. Her mother comes in to announce that Drosselmeyer's nephew has arrived from Nuremberg. By swearing that she would love him in spite of his looks, Marie broke the curse and made him human again. He asks her to marry him. She accepts, and in a year and a day, he takes her away to the doll kingdom, where she is crowned queen.

Publication history

[edit]The story was first published in 1816 in German in Berlin by In der Realschulbuchhandlung in a volume entitled Kinder-Mährchen, Children’s Stories, which also included tales by Carl Wilhelm Contessa and Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué. It consisted of 14 chapters, perhaps intended to be read over the 14 days between Christmas and Epiphany. The title page included a colored plate of the Mouse King from a drawing by Hoffmann himself. Chapters 7 to 9 are known as the Fairytale of the Hard Nut, the story within the story.[2]: 230 This is the story which Godfather Drosselmeier tells to Marie over three nights following the battle of the Nutcracker and Mouse King. It describes the birth and enchantment of Princess Pirlipat, and continues until young Drosselmeier breaks the enchantment, restores her beauty and is transformed into the nutcracker. This part of the story is typically omitted from ballet adaptations.

The story was republished in the first volume of Hoffmann’s short story collection, Die Serapionsbrüder, (1819-20). It was preceded and followed by a conversation among four fictionalized "Serapion Brethren" about its merits. It had the same chapter structure as the original, but Hoffmann's illustration was omitted. The Serapion Brethren was the name of a literary club that Hoffmann formed in 1818.

Nutcracker was reprinted in Germany again in 1840 as (loosely translated into English) Nutcracker and Mouse King, a most adorable children's fairy tale after E.T.A. Hoffmann with the latest picture delights in 10 finely illuminated copper plates after original drawings by PC Geißler. Each of the ten chapters included a colorize plate by Peter Carl Geissler.[3]

David Blamires (lecturer at Manchester University’s Department of German Language and Literature) observed that William Makepeace Thackeray was the first to publish The Fairytale of the Hard Nut portion of the story in English, which he titled The History of Krakatuk. It appeared in a British newspaper, the National Standard, in 1833. It seemed to be lost but was recovered by Lewis Melville and republished in 1929 in Great German Short Stories edited by Melville and Reginald Hargreaves.[2]: 237 [4]

The first full children's version of the story published in Britian was by Ascott R. Hope published by T. Fisher Unwin in 1892 in his ‘Children’s Library’ series. According to Blamires, "[Hope] does not attempt to explain features of German life that may seem strange to his readers, but instead eliminates them or gives English equivalents".[2]: 242 [5]

Blamires also described a British adaption called Nutcracker and Mouse-King, which was published by George G. Harrap & Company. He stated that it was published in 1919, in the aftermath of WWI; however, according to the printed date on the publication page, it was actually published in 1916 during the war. Nonetheless as was the trend at the time, all German references were removed. Hoffmann was not mentioned on the title page, only E. Gordon Browne, the adaptor. Fritz and Marie were replaced with Dick and Molly; godfather Drosselmeier with Uncle Christopher; etc. [2]: 243 .[6] Four color plates by Florence Anderson depicted a pretty side to the story as opposed to the starker engravings by Bertall (illustrator for the Dumas adaptation), which Blamires deemed more consistent with the darker aspect of Hoffmann's tale.[2]: 244

Hoffmann's Nutcracker was not as extensively published in Britian in the 19th century as other German stories. Blamires speculated that it was not sufficiently educational or moralistic for the time.[2]: 244

The story was published in full in 1853 in the U.S. in a translation by Mrs. St. Simon in New York by D. Appleton and Company with wood-engraved illustrations by Albert H. Jocelyn.[7]

An English version was published in 1886 in a translation of the first volume of Die Serapionsbrüder by Alexander Ewing. The preface to this translation states that the already well-known story was only familiar to English readers at the time indirectly, through a secondary translation of an earlier French edition.[8]: iii

In 1930, an edition of "The Nutcracker and the Mouse-King" was published by Albert Whitman and Company in Chicago in a translation by Louise F. Encking with illustrations by Emma L. Brock.[9] Encking was Supervisor of Children's works at the Minneapolis public library at the time,[10] and Brock, also a librarian, who went on to become a prolific writer of children's books. They omitted Hoffman's ending in which Marie's love restores Nutcracker to his human form as well as their return to the Kingdom of the Dolls.

Ewing's translation was included in the 1967 collection The Best Tales of Hoffman released by Dover Publications. In 1996, Dover also published a version of the translation, abridged by Bob Blaisdell with illustrations by Thea Kliros, as The Story of the Nutcracker.[11] It was part of the Dover Children's Thrift Classics series. It contained 30 new illustrations. Blaisdell and Kliros were both prolific contributors to this genre.[12][13]

Ewing's translation was also included in the 2018 collection, The Nutcracker, The Sandman, and other Dark Tales: The Best Weird Tales and Fantasies of E. T. A. Hoffmann introduced and edited by Grant Kellermeyer by Oldstyle Tales Press, with gothic-style sketches by Kellermeyer including one of a sinister Godfather Drosselmeier holding Nutcracker.[14] Kellermeyer is a publisher and contributor to many publications primarily dealing with classic ghost and horror stories.[15] According to the Oldstyle Tales Press website, he is its founder and editor.[16]

Lisbeth Zwerger, winner of the Hans Christian Andersen Award for Illustration for her lasting contribution to children's literature, illustrated a German language edition by Neugebauer (Salzburg, Austria), 1979. These illustrations were subsequently used in an English translation by Anthea Bell as The Nutcracker and the Mouse-King, by Picture Book Studio (Boston Massachusetts), 1983.[17] She also did an entirely new set of illustrations for a young children's book adaption by Susanne Koppe as The Nutcracker by North-South (New York), 2004.[18]

A modern translation by Ralph Manheim, one of the most acclaimed translators of the 20th century,[19] with illustrations by Maurice Sendak was published in 1984 by Crown Publishers. A New Your Times article described the translation as fervent and fiery yet direct.[20] Sendak, known for his depiction of strong, independent children did so in his illustrations of Nutcracker:

To accentuate Hoffmann's juxtaposition of the ignorant Stahlbaums and their astute daughter, he differentiates their eyes. The Stahlbaums have a shallow, lifeless look while Marie has wide eyes that emanate acumen and optimism. When Sendak depicts her traveling in a gondola to the Nutcracker's kingdom, her expression extends miles across the sea [pg. 77]. In his final illustration, he poses her on her toes with a confident, upward gaze [pg. 98].

— Robin Lily Goldberg (2009)[21]

Sendak had been asked by Choreographer Kent Stowell to design and dress a new ballet production of Nutcracker for the Pacific Northwest Ballet and the book grew out of that collaboration.[20]

Jack Zipes, a scholar specializing in fairy tales and German literature, wrote the introduction to versions of the story by E.T.A. Hoffmann and Alexandre Dumas published by Penguin Classics in 2007. Joachim Neugroschel, a multilingual literary translator, translated both versions. Zipes included a short biography of Hoffmann in which he explored his musical and literary motivations.[22]

Antecedents

[edit]

Kellermeyer's introduction to Nutcracker notes that Hoffman built on the legacy of European folk lore classics, most notably, King Thrushbeard ("König Drosselbart"), the apparent source of Drosselmeier’s name. In this story the daughter of the king rejects various suitors, including King Thrushbeard who she considers ugly. After she is tricked into marrying him, she learns to love him in spite of his looks, just as Marie falls in love with the ugly Nutcracker (who also has a weird beard).[14]: 359

David Blamires (lecturer at Manchester University’s Department of German Language and Literature) noted a correspondence between the Mouse King and the "dragon representing evil incarnate in the Book of Revelations (12:3)",[2]: 230 which also includes the seven-headed beast. The number seven appears numerous times in the book. For example, the Mouse King has seven crowns, the Mouse Queen has seven children killed in court-clockmaker, Drosselmeyer's mouse traps. Christian Zacharias Drosselmeier, clockmaker Drosselmeier cousin, has the Krakatuk in his possession for seven years. Young Drosselmeyer is required to take seven steps backward without stumbling after giving the shelled Krakatuk to Pirlipat. However, he trips while taking the seventh step when he steps on the Mouse Queen. Furthermore, Marie in the story, and listener to it, is seven years old, although in the English translation of the Dumas version her age was changed to seven and a half,[2]: 238 which spoiled the parallel somewhat.

Hoffman uses one of the "most widely diffused folktale-types, 'The Dragon Slayer'" in which the male hero is wounded while trying to save the princess. He kills the dragon, and after more drama, he marries her. However, in Hoffman's version, Nutcracker is the initial intended victim, Marie participates in the battle in which she saves Nutcracker, and both are wounded.[2]: 230

A key aspect of Hoffman's tale is the appearance of characters with the same name, for example, Godfather Drosselmeier, story teller, and Drosselmeier, the court clockmaker, and various other Drosselmeiers in his story. A similar multiplicity of names occurs in The Four Facardins a book by Anthony Hamilton which Marie's mother reads to her as she lies in bed recovering from her wound.[2]: 230

A feature of "Nutcracker" which sets it apart from other Children's fairytales at the time was an avoidance of moralizing intended to turn children into little adults or to frighten them about what would happen if they continued to behave badly from an adult perspective. A prominent example of such a story is Struwwelpeter by Heinrich Hoffmann (not to be mistaken with E.T.A. Hoffman). In one of the cautionary tales in Struwwelpeter a mother tells her son not to suck his thumb. When he persists a fleet-footed tailor cuts it off with large sheers. However, Nutcracker exemplified friendship, loyalty and resourcefulness. E.T.A. Hoffman's more subtle approach may have been inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau who promoted more lenient child-rearing practices. He advocated for "strategies less overt and designed to conceal their aim rather than reveal it."[24]: 28

Motivation

[edit]According to Jack Zipes, Hoffmann was "an accomplished artist who became a gallant man-about-town". He had composed an opera, directed plays, and was a "disciplined writer, constantly creating new types of tales and novels". His official occupation was that of a jurist and he eventually became a judge. While he felt confined by his bourgeois life, he was able to escape it through his imaginative writing.[22]: xi His stories typically began by reporting mundane events which were quickly upset by a confused conflation of reality and fantasy that was confounding to the characters and the reader alike.[22]: xix "Nutcracker" for example, begins with a description of a familiar scene of Marie and her brother Fritz waiting to enter a room full of Christmas decorations and toys. But after Marie falls in love with the Nutcracker, one of their gifts, she is propelled into a strange fantasy world imperceptible to the rest of her family (other than godfather Drosselmeier), which they refuse to believe.

There is an autobiographical element to the story which is modeled on the family of close friend Julius Hitzig. In 1816, Hitzig had three children, Louise, Marie and Fritz. Like Drosselmeier, Hoffman gave them an illuminated castle which he made himself. His friend is prudish and very strict with the children, which was the norm at the time. Hoffman conveys this my naming Marie's family Stahlbaum or "Steel Tree" signifying the rigidity of the family dynamic.[22]: xxi Louise, the oldest child, has begun to lose her childish creativity and does not feature in the story very much.

However, this story is not just about his friends family. It is part of a larger project which Hoffman described in the frame for the story included in The Serapion Brethren (Die Serapionsbrüder. The stories are discussed by fictional members of the real-life Serapion Brethren. Lothair [i.e. presumably a stand in for Hoffmann] says he has written a book for children. He recites the story and asks for the opinion of other members which leads to the following exchange:

Tell me, dear Lothair," said Theodore, "how you can call your 'Nutcracker and the King of the Mice' a children's story? It is impossible that children should follow the delicate threads which run through the structure of it, and hold together its apparently heterogeneous parts. The most they could do would be to keep hold of detached fragments, and enjoy those, here and there.". . ."And is that not enough?" answered Lothair. "I think it is a great mistake to suppose that clever, imaginative children–and it is only they who are in question here–should content themselves with the empty nonsense which is so often set before them under the name of Children's Tales. They want something much better; and it is surprising how much they see and appreciate which escapes a good, honest, well-informed papa."

— E.T.A. Hoffman (1819) translated by Alexander Ewing (1886)[8]: 273

In other words, he was seeking to create a new and substantive fairytale designed for clever children to spur their imagination. Presumably "papa" could gain insights from reading it as well. He goes on to say that he had first told the story to his sister's children; and they were delighted. Fritz was especially enthusiastic about the description of the toy soldiers and the battle. As the battle is being lost the Nutcracker shouts "A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!" a quote from Shakespeare's Richard III which Fritz knew nothing about but that did not dampen his enthusiasm.[8]: 274

Another member comments:

I cannot help telling you that, if you bring this tale before the public, many very rational people--particularly those who never have been children themselves (which is the case with many)--will shrug their shoulders and shake their heads, and say the whole affair is a pack of stupid nonsense; or, at all events, that some attack of fever must have suggested your ideas, because nobody in his sound and sober senses could have written such a piece of chaotic monstrosity.[8]: 274

To which, Lothair declares that while a good work flashes out in all directions, it must contain "a firm kernel within it".[8]: 275

By "very rational people" Hoffmann seems to be referring to the smug and narrow-minded bourgeois, who he referred to as "Philistines".[25]: 111 According to artist and German literary scholar, Peter Bruning, he developed an antipathy for such people, when during an earlier period in his life, he more or less voluntarily became a sort of bohemian. During that period, he gave music lessons to the children of rich burgers to earn a living. However, he was resentful of the parent's superior attitude and was also upset by the "bourgeois in himself, as his own alter ego". This led to open hostility in some of his stories; but his criticism was better natured and humorous in his first fairytale The Golden Pot: A Modern Fairy Tale ("Der goldne Topf. Ein Märchen aus der neuen Zeit"), 1814.[25]: 113 Nutcracker followed in the same vein.

Bruning also noted that Hoffmann was preoccupied with Schelling’s theory of the world soul in which nature emerges from the spirit. In particular he embraced the idea that only artists could possess the intuitive knowledge of the absolute in nature; i.e.: the "contradiction between nature and spirit reaches a state of harmony in the process of artistic creation". However, he preferred to adopt Gotthilf Heinrich Schubert, interpretation of Schelling.[25]: 275

Hoffmann adopted Schubert's world view so thoroughly that they have been referred to as "kindred spirits".[26]: 216 They believed the quest for transcendence can have tragic consequences. Complete abandonment of the mundane can lead to rejection and insanity. However, a harmonious balance of the two realms can be attained in the life of a fortunate individual. These interpretation found their "ultimate poetic expression in The Golden Pot. This story ends in triumph. After overcoming many obstacles including being trapped in a ink bottle, the hero is transported to "Atlantis the world of poetry".[27]: viii

In "Nutcracker" young Marie's is also able to achieve transcendence with the encouragement of godfather Drosselmeier (Hoffmann's alter ego) and she is able to save Nutcracker where as Drosselmeier himself could not. He spoke to Marie as follows:

Why, dear Marie, you’ve been given more than I, than any of us. Like Pirlipat, you are a native-born princess, for you rule a bright and lovely kingdom. But you’ll have to suffer a lot if you want to take charge of poor, deformed Nutcracker, since Mouse King persecutes him anywhere and everywhere. However, I’m not the one who can save him! Only you can rescue him. Be strong and loyal.

— E.T.A. Hoffman (1816) translated by Joachim Neugroschel (2007)[22]: 41

At the end, the narrator suggests transcendence might also be attained by childlike adults "if you only have the right eyes to see them with".[22]: 62

On the other hand, according to Horst S. Daemmrich (German literature scholar and self-professed existentialist), [28] in contrast with Maries joy and marvel as she tours Candyland, there is an often overlooked dark side to the narrator's description. The inhabitants of Candyland suffer from toothaches and are forced to fend off insects who attempt to eat their candy homes. The dancers in the ballet that she views there resemble that of Drosselmeier's mechanical dancers which boringly circle around in his toy castle. Furthermore, an omniscient "Confectioner" covers the "tragic dimensions" of Candyland (Daemmrich's assessment) with frosting. He states that "Hoffmann lacks all shallow optimism" and that "Hoffmann seriously questions the mission of art and the artist in Nutcracker and the King of Mice".[29] Daemmrich's analysis of Hoffmans work indicates that "Hoffmann is a far more ambiguous, complex, and generally modern author than were his German contemporaries of the Romantic period."[30]

Michael Grant Kellermeyer also called attention to darker interpretations of Nutcracker. One of the most unsettling of these was a comment regarding the last paragraph:

So then they [Marie and Nutcracker] were formally betrothed; and when a year and a day had come and gone, they say he came and fetched her away in a golden coach, drawn by silver horses. At the marriage there danced two-and-twenty thousand of the most beautiful dolls and other figures, all glittering in pearls and diamonds; and Marie is to this day the queen of a realm where . . . the most wonderful and beautiful things of every kind-are to be seen-by those who have the eyes to see them. [Emphasis added]

— E.T.A. Hoffman (1819) translated by Alexander Ewing (1886)[14]: 41

Even, conventional interpretations have highlighted the ambiguity of the ending: "The marriage can be read simultaneously as a fairy-tale happy ending in the fantastical world, and as a yet unfulfilled hope . . . in the real world".[31] Kellermeyer's interpretation of the ambiguity goes well beyond that. He noted that the celestial description of Marie's wedding and kingdom, qualified by "they say", could be a euphemistic way of referring to Marie's death perhaps equivalent to saying that she went to a better place. He suggested that:

Marie’s wound [which occurred when she fell against the glass cabinet during the battle with the mice] has become infected and her immune system weakened, causing her hallucinations and estranging her from her family. Within a year the infection proves fatal, and the only person who seems to understand her – her imaginary friend, Nutcracker – embodying Death, returns to take her to paradise.

— M. Grant Kellermeyer (2018)[14]: 469

While hinting at ambiguities such as these would seem out of place in a story that Hoffmann intended for young children (even Marie Hitzig herself, the daughter of his friend) he was prone to include story elements beyond their understanding, for example the reference to Richard III noted above. It suggests that he included a hidden layer of meaning intended for adult readers or perhaps to satisfy his artistic sensibilities.

Ritchie Robertson, who translated and commented on a number of Hoffman's stories noted a progression in outlook in Hoffman's works. The Golden Pot (1814) (also Nutcracker 1816) was written early in his romantic period and was optimistic about the potential for transcendence. The Sandman (1817) was a "negative counterpart" in which the protagonist's immersion in imagination led to madness and suicide. In Master Flea (1822), there is a rejection of fantasy. Finally, in My Cousin's Corner Window (1822) , written on his death bed, there is no supernatural component at all, instead there was a focus on the here and now as seen from the crippled poet's window overlooking the center of Berlin.[27]: viii This progression followed a trend in German literature away from Romanticism to Biedermeier, an exploration of the modest possibilities of happiness available in one's immediate world after the devastation of the Napoleonic War.[27]: ix

Psychological perspectives

[edit]

Lisa Zunshine, a scholar of cognitive literary theory, began her analysis of Nutcracker with the inference that the Mouse King was inspired by Albrecht Dürer's (a favorite of Hoffmann) Saint George and the Dragon. Saint George, she wrote, was a stand-in for Christ who was often depicted in combat with "basilisks, dragons, and many-headed serpents”. Presumably her parents would have found it acceptable if Marie expressed belief in Saint George and the Dragon. However, they were adamant in refusing to accept her experience with Nutcracker and the Mouse king. Zunshine also noted that her parents fostered a belief in the myth that the Christ child brought the gifts under the Christmas tree, which was the German tradition at the time.[32]: 225-226 Despite the acceptability of some mystical beliefs, her father threatened severe punishment if she did not disavow her fantastic experience, "Listen, Marie. Forget about your antics and your fantasies! If you ever repeat that the deformed and simpleminded Nutcracker is the nephew of Herr Supreme Court Counselor, I'll hurl all your dolls out the window".[22]: 58

Marie tenaciously gave preference to her "lived experience" over that of her parent's explanation that she was delerious. Zunshine noted that modern cognitive studies confirm that children her age are skeptical of authority figures in similar circumstances.[32]: 238

Also, while Godfather Drosselmeier was initially supportive of Marie, he eventually betrayed her by calling her descriptions of the battle "stuff and nonsense!". This is also consistent with cognitive theory which posits that adults often unconsciously adapt their beliefs to be consistent with that of their peers.[32]: 238

She credits Hoffmann and his audience with realistic expectation long before the development of "cognitive psychology through conceptual frameworks available to them, which is to say, by evoking the unfettered imagination of the child and the hopeless philistinism of the parent".[32]: 244

Elizabeth Elam Roth, a dance critic, explored what she perceived as Freudian elements in Hoffmann's story which were amplified in Mikhail Baryshnikov’s ballet where Clara (Marie renamed) is a young adult dancer costumed to look younger. Baryshnikov depicted Clara's growing sexual awareness, which is found in Hoffman's Maria, although less obvious, for example: "When Marie understands . . . that her nutcracker toy is actually the transmogrified nephew of Godpapa Drosselmeier, she immediately stops cuddling and fondling him as she does her other dolls, realizing that this behavior is unseemly."[33]: 39 The sexual themes are even more explicit in the Maurice Sendak’s Nutcracker ballet where Clare is twelve years old rather than seven.[33]: 40

Although born about 80 years before Freud, Hoffmann seems to have Freudian insights. Roth noted, for example, that oral gratification, central to infants attachment to the one who feeds it, is a child's first libidinal instinct. "Had Hoffmann not been a proto-Freudian, he perhaps would have chosen an ordinary toy soldier, even a teddy bear, to come to life [rather than a nutcracker] whose reason for being is the oral task of cracking nuts and feeding them to Marie and her family".[33]: 40 Freud himself commented on Hoffmann insights into unconscious motivations in his analysis of Hoffmann's novella "The Sandman", although he did not reference Nutcracker.[33]: 39

Literary devices

[edit]Nutcracker is a "child-friendly analog" to Hoffmann's disturbing fantasies for adults in which the protagonists retreated so far into their realized worlds that they became misfits and outcasts. In order to make his tale more appropriate and engaging for children, he employed a number of literary devices that have become foundational to children's fantasy literature.[34] In a journal article, Maria Tartar described a number of the innovations in Nutcracker and cited well known authors who used them knowingly or not:[24]

Portal fantasy. The portal fantasy was probably the most influential of his innovations. In Nutcracker Marie and young Drosselmeier enter the Kingdom of the Dolls by way of the sleeve of her father's fur coat which they reach by entering his wardrobe. The precedent for C.S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia is unmistakable: Lewis's Lucy is transported to Narnia after entering her father's wardrobe as she feels his fur coat against her face. The rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland is a world famous example. In J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter books, the children commuted to Hogwarts by way of Platform nine and three-quarters and the red steam engine.[24]: 31

Although not specifically mentioned by Tartar, a story by L. Frank Baum and W.W. Denslow, Dot and Tot of Merryland, has a number of parallels with Nutcracker, including a portal. The children, Dot and Tot, enter a fantasy land when their boat drifts into a side channel that takes them to a tunnel guarded by the Watchman. They persuade him to let them in and they pass through the portal into the seven astonishing valleys of Merryland.[35][36]: 46

Marie effortlessly becomes small enough to ascend the stairs into the sleeve portal together with Nutcracker. (The two are depicted as about the same size by Encking and Brock.) The narrator simply takes it for granted.[37]: 98-100 Marie does not share Alice's need for pills or potions to change size, as in the The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Neither is her young age a barrier to her marrying Drosselmeier, then the restored King of the Kingdom of the Dolls, and becoming Queen. Again, the narrator takes no notice of any barrier.

Eye candy. As Marie (pampered daughter of a bourgeoisie family) tours the Kingdom of the Dolls with Young Drosselmeier, she was thrilled to see sugar coated fruits. houses shuttered by sweets, lemonade fountains and rivers, etc. Such sites were also sure to thrill young children listening to the story. Similar enticements were used in Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, although in his tale, Charlie is a starving waif who desperately wants "CHOCOLATE" rather than cabbage soup. Charlie tours the chocolate factory with four other children who succumb to the temptations of gluttony, gum chewing, avarice and TV addiction. Charlie is able to resist the temptations and is rewarded with an inheritance of the factory itself. Thus, it is more a cautionary tale like Struwwelpeter than an exploration of the "conflicts between the banality of everyday life and the aesthetic pleasures of art" as is Nutcracker.[24]: 26

In Baum and Denslow's Dot and Tot, the children enter a valley made of candy, where even the inhabitants are candy, which has amusing consequences. For example, Tot bites off a thumb and two fingers of "candy man", which he doesn't seem to mind in fact he is proud that Tot found them delicious. [36]: 84

Aesthetic pleasures. As described by Tartar, Hoffman uses candy as a "gateway drug". "Once [Marie] abandons the gluttonous pleasures of sweets, she enters a verdant landscape that captures the synesthetic wonders of a fully realized natural landscape".[24]: 27 Dot and Tot also have an enriching experience. Dot in particular returns more energetic and healthier.[36]: 225 However, Dahl's Charlie simply makes a transition from "poverty to plenty", there is no evident spiritual or intellectual transcendence.[24]: 26

Nonsense. At the beginning of his tale of the hard nut (the tale within the tale) Godfather Drosselmeier recites a long series of nonsense clock sounds intermixed with obscure references to battle which Marie witnessed:

Pendulum, had to hum, didn’t wish to fit, clocks, clocks, clock pendulum, had to hum, softly hum, bells boom, bells blast, limp and lame and honk and hunk, doll girl, don't worry, scurry, ring the bell, bell is rung, bell is sung, to drive away Mouse King today, now the owl comes flying fast, pack and pick and pick and pack, chimes are jingly, clocks, hum, hum . . .

— E.T.A. Hoffman (1819) translated by Alexander Ewing (1886)

Hoffmann seems to use the strange almost hypnotic chanting to signal a transformation from the banal to the fantastic.[24]: 33

Famously, nonsense was fundamental to the works of Victorian authors Lewis Carrol (eg. Through the Looking Glass) and George MacDonald (eg. The Princess and the Goblin) although they were primarily influenced by Novalis (whom Hoffmann also admired). MacDonald's Phantastes included an epigram by Novalis that seems to indicate his belief that "anarchy’s role in the nonsensical [is] a necessary step in achieving greater harmony".[38] In any event, the rhythmic repetition of sounds in songs by MacDonald's young hero, Curdie, to deter the Goblins is reminiscent to the Drosselmeier's chant.[39]: 19

In the U.S., Baum and Denslow have clowns sing nonsense songs to Dot and Tot in Merryland's Clown Country. Their houses have platforms on top where they perform.[36]: 60

Invitation to participate. The self-referential narrator in Nutcracker addresses his audience and makes a request: "I turn to you, gentle reader or listener–Fritz, Theodor, Ernst [the last two are Hoffman's own names]–or whatever your name may be, and I picture you vividly at your last Christmas table. You will then envisage how the children halted, in silence and with shining eyes" The children listeners (and "those who have eyes to see") are thus invited to use their imagination to participate in the story creation–to use their minds eye to create (as in the final line of "Nutcracker") "the most splendid and wonderous things".[24]: 34

No return. It is the norm in Children's stories of fantasy places, that the children protagonists return home after their visit, whether it be to "Wonderland", "Neverland" or "Merryland". In The Wizard of Oz, (the movie not the book) Dorothy famously repeats, "There is no place like home" as she clicks her ruby slippers three times and returns home to Kansas. Marie does return after her first tour of the Kingdom of the Dolls. In her ecstasy, she rises higher and higher but then falls and finds herself back in bed. However, after Nutcracker (now the king), takes her there as queen, she never returns.[24]: 30

The Encking and Brock's version of story subverts Hoffmann's intent by ending when Marie returns to her bed after her first tour of the Kingdom of the Dolls. Their last paragraph wipes away much of the real-versus-fantasy ambiguity of Hoffmann's story. Hoffman's final paragraph is simply "And that was the tale of Nutcracker and Mouse King."[22]: 62 In their version it is, "Yes, in the merry Christmas time children dream wonderful things. And beautiful dreams are also fairy tales, as is this one of the Nutcracker and the Mouse King".[37]: 123 Perhaps this change was made to be more consistent with the sweetened story depicted in the ballet. The introduction states,

The gay imaginings in the book, especially those in the Land of Dolls, amused Peter Tschaikovsky, the great Russian musician, and he has written the music of “The Nutcracker Suite” all about this tale. The Chinese dance, the waltz of the Flowers and the dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy are all drawn from these chapters of Marie’s visit to Toy Land with the Nutcracker. And you can see the gay little people when you hear the music, just as you can when you read the story.

— Emma L. Brock (1930)[37]: viii

Dumas version

[edit]

Alexandre Dumas, was an admirer of Hoffman and had published a story about him before adapting Hoffmann's story for a French audience titled Histoire d'un casse-noisette (The Tale of the Nutcracker).[22]: xxvi The publication date is sometimes given as 1844[41] or 1845.[2]: 239 The copy in the National Library of France has a printed date of 1845 but is stamped 1844,[40] which suggests that it was received prior to the official publication date.

According to David Blamires, the Dumas version was an adaptation rather than a translation. The numerous illustrations by Bertall, which appeared on almost every page, sometimes two per page, added to the appeal.[2]: 238

Dumas's proficiency in German was minimal so it appears that he may have used an earlier translation into French. In the preface he set up a frame in which he is recounting Hoffmann's story to entertain a group of unruly children. He makes it clear that Hoffman is the originator.[22]: xxvi

An English translation was first published in two volumes by Chapman & Hall, London in c.1847 as The History of a Nutcracker.[42] It included Bertall's illustrations; but the translator was not identified.[2]: 238 It was reprinted as the second story in A Picture Story Book (c.1875) by George Routledge and Sons. A colorized version of one of Bertall's illustrations was used as the frontispiece for the book.[43][44]

Oxford University Press published a translation by Duglas Munro in 1976 with illustrations by Phillida Gili[45] Munro was a Dumas scholar who donated his a vast collection of Dumas materials to the University of Manchester library.[46] Sarah Ardizzone did a children's book translation in 2015.[47] Ardizzone also wrote an illustrated article for The Guardian about Dumas and his version of Nutcracker after the book came out.[41]

While Hoffmann was intentionally ambiguous about his intended audience, Dumas was clearly writing for children, as consistent with its publication in Le Nouveau magasin des enfants, a serial devoted to new children's stories.[48][2]: 125 Hoffman's frame is very detailed concerning the time, place and atmosphere of Marie and Fritz's home. Dumas is vague. He does state that the story occurs in Nuremberg,[49]: 127 but highlights that it is where toys are made:

And the most educated among you [Dumas's audience of young children] know, without a doubt, that Nuremberg is a German city famous for its toys, its dolls, and its Punchinellos. Indeed, it sends caseloads of these wondrous things all over the world, so that the children of Nuremberg must be the happiest on earth . . .

— E. T. A. Hoffman (1816) translated by Joachim Neugroschel (2007)[22]: 69

While the reference to Nuremberg seems specific, the emphasis on toys makes it a sort of "Toy City" and thus consistent to a "Once-upon-a-time" frame, quite different from Hoffman's. Chapter 1 of Chapman and Hall and George Routledge and Sons, looser translations from the 1800's, actually begins with "Once upon a time". The more accurate translation by Neugroschel begins, "Once, in the town of Nuremberg, there lived a highly esteemed presiding judge known as Presiding Judge Silberhaus, which means Silver House."[22]: 68

Dumas's adaptation has been described as a "sweeter"[50] or "watered-down"[20] version of the Hoffman original. These assessments appear more appropriate to the ballet derived from Dumas's adaptation than his published story. Choreographer, Marius Petipa, for example, added a scene for the original 1892 ballet in which children performers (Polichinelle) emerge from under Mother Ginger's large skirt to dance with her.[51]

However, comparison of the texts indicates that Dumas's version was enhanced with more vivid descriptions and even gruesome details which were also depicted in Bertall's illustrations. Drosselmeier (Dumas calls him Drosselmayer), for example, is described as stooped and wearing an eye patch because "he had lost his right eye because of an arrow shot by a Caribbean chieftain".[22]: 117 In another example from the description of the battle with the Mouse King, Dumas includes description of mice being impaled by a toy cook wheeling a skewer and one of the dolls is disemboweled by the mice. There is also a threat of torture:

Two [mouse] sharpshooters pounced on him [the Nutcracker] and grabbed him by his wooden cape. At that same moment, they heard the voice of Mouse King, whose seven heads were hollering. 'If you value your necks, take him alive. Remember that I have to avenge my mother. Her torture has to horrify any future Nutcrackers.

— Alexandre Dumas (1845) translated by Joachim Neugroschel (2007)[22]: 95

On a more sentimental note, when Nutcracker was about to be captured by the Mouse King, Marie sobbed, "Oh! My poor Nutcracker! Oh! My poor Nutcracker!", to which Dumas adds: "I love you with all my heart! And now I have to watch you perish like this!” [22]: 21&96 Numerous vibrant details like these were added to Hoffmann's original story.

David Blamires pointed out a minor difference between the two versions, perhaps due to a misunderstanding. In Hoffmann's version, the requirement for Princess Pirlipat's rescuer was that he had never worn boots. In Dumas's version the requirement was reversed, i.e. he must always have worn boots. Presumably the wearing of boots is an indicator of the transition to manhood.[2]: 239 Young Drosselmeier looks quite dashing in his boots in Bertall's illustration of him as he presents the shelled Krakatuk to Princess Pirlipat.

Dumas eventually calls young Drosselmeier "Nathaniel", although Hoffman does not reveal his given name.[2]: 239 Michael Grant Kellermeyer suggested that Hoffman deliberately blurred the distinction between Godfather Drosselmeier and young Drosselmeier, perhaps expressing a desire to transfer some of Marie's affection for young Drosselmeier to the older man. "Drosselmeier appears to disguise his ego in the figure of Nutcracker, and Marie only breaks the spell by declaring her love for “Dear Drosselmeier" (meaning the nephew, but equally applying to the uncle)".[14]: 469 Omitting young Drosselmeier's given name seems consistent with that premise.

Blamires speculated that the name Nathaniel given by Dumas may have been taken from a character in Hoffmann's The Sandman.[2]: 239 In that story, Nathaniel falls in love with a wooden doll who is or seems alive. That would be a reversal in the gender roles of Marie and Nutcracker.

Zipes commented that while the Dumas adaptation was "not poorly written", it lacked some of Hoffman's irony and his ridicule of the bourgeoisie ("philistines") confining attitudes toward child rearing. For example, the Marie's family name Stahlhaus ("Steel House"), suggesting strict rules, was changed to Silberhaus (“Silver House”); and Dumas's Drosselmeier appears to adore the Silberhaus children rather than being ambivalent toward them.[22]: xxvi On the other hand, translator Sarah Ardizzone was enticed by the Dumas adaptation because the tale was restored to its "oral story-telling tradition".[41] Munro, Dumas scholar and translator, stated that, "as is the usual case when he handled someone else's material, [Dumas] has greatly improved upon the original".[43]

Adaptations

[edit]- Composer Carl Reinecke created eight pieces based on the story as early as 1855.[53] The pieces would be performed with narration telling a short adaptation of the story.[54]

- The Nutcracker (Histoire d'un casse-noisette, 1844 or 1845) is a retelling by Alexandre Dumas, père of the Hoffmann tale, nearly identical in plot. This was the version used as the basis for the 1892 Tchaikovsky ballet The Nutcracker, but Marie's name is usually changed to Clara in most subsequent adaptations.

- The Enchanted Nutcracker (1961) is a made-for-TV adaptation of the tale, written in the style of a Broadway musical, starring Robert Goulet and Carol Lawrence. It was shown once as a Christmas special, and never repeated.

- The Nutcracker (Polish: Dziadek do orzechów) is a Polish 1967 film directed by Halina Bielińska.

- It was also adapted into the 1979 stop motion film Nutcracker Fantasy, the traditional animation films Schelkunchik (Russia, 1973), and The Nutcracker Prince (Canada, 1990)[55] and the 2010 film The Nutcracker in 3D.

- In 1988, Care Bears Nutcracker Suite is based on the story.

- The story was adapted for BBC Radio in four weekly 30-minute episodes by Brian Sibley, with original music by David Hewson and broadcast 9 December to 30 December 1991 on BBC Radio 5, later re-broadcast 27 December to 30 December 2010 on BBC Radio 7. The cast included Tony Robinson as "The Nutcracker", Edward de Souza as "Drosselmeyer", Eric Allen as "The Mouse King", James Grout as "The King" and Angela Shafto as "Mary".

- The Nutcracker Prince is a Canadian 1990 animated film directed by Paul Schibli, with Kiefer Sutherland as the Nutcracker/Hans, Megan Follows as Clara, Mike MacDonald as Mouse King, Peter O'Toole as old soldier Pantaloon, an old soldier and Phyllis Diller as Mouse Queen.

- In Mickey Mouse Works, the Mickey Mouse Nutcracker (1999) is an adaptation of this tale, with Minnie Mouse playing Marie, Mickey playing the Nutcracker, Ludwig Von Drake playing Drosselmeyer, albeit very briefly, and Donald Duck playing the Mouse King. Goofy is also featured as an extra.

- In 2001, a direct-to-DVD CGI-animated movie, Barbie in the Nutcracker, was made by Mattel Entertainment starring Barbie in her first-ever movie and features the voices of Kelly Sheridan as Barbie/Clara/Sugarplum Princess, Kirby Morrow as the Nutcracker/Prince Eric, and Tim Curry as the Rat King.

- There is a German animated direct-to-video version of the story, The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, released in 2004, which was dubbed into English by Anchor Bay Entertainment, with Leslie Nielsen as The Mouse King and Eric Idle as Drosselmeyer. It uses only a small portion of Tchaikovsky's music and adapts the Hoffmann story very loosely. The English version was the last project of veteran voice actor, Tony Pope, before his death in 2004.

- Tom and Jerry: A Nutcracker Tale is a 2007 holiday themed animated direct-to-video film produced by Warner Bros. Animation.

- In 2010, The Nutcracker in 3D – a live-action film, based only loosely on the original story – was released.

- In 2012, Big Fish Games published a computer game Christmas Stories: The Nutcracker inspired by the story.

- The Nutcracker (2013) is New Line's live-action version of the story reimagined as a drama with action and a love story. It was meant to be directed by Adam Shankman[56] and written by Darren Lemke.[57] The film’s production was halted in late 2012 and as of 2022 it has yet to be made.

- Puella Magi Madoka Magica the movie: Rebellion (2013) adapts many of the themes and imagery from the story. Most notably the final battle sequence centering on "The Nutcracker Witch".

- In November 2014, The House Theatre of Chicago adapted the story for its West Coast premiere at New Village Arts Theatre that featured Edred Utomi, Brian Patrick Butler and Jennifer Paredes.[58]

- On December 25, 2015, German television station ARD aired a new live-action adaptation of the story as part of the 6 auf einen Streich (Six in one Stroke) television series.[59]

- In 2016, the Hallmark Channel presented A Nutcracker Christmas film that contains a number of selected scenes of the 1892 two-act Nutcracker ballet.

- Disney's 2018 live-action film The Nutcracker and the Four Realms is a retelling of the story; it is directed by Lasse Hallström and Joe Johnston.[60]

- In 2021 and 2022, PBS broadcast The Nutcracker And The Mouse King, John Mauceri's reimagining of the story, narrated by Alan Cumming in concert with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. Mauceri presents the entire story, from “how the young man got into the nutcracker” to where the characters are “today”, using Tchaikovsky's music to highlight a story very different from the familiar ballet scenario.[61][62]

- In 2023, Erika Johansen's novel The Kingdom of Sweets was published by Penguin Random House. In this version of the story, Natasha and Clara are twins. Drosselmeyer calls "Clara the light, and Natasha the dark" and Natasha spends her life ignored or given unpleasant gifts unlike her beloved sister. When both girls visit the Sugar Plum Fairy, Natasha finds out she can have anything she wants, for a price, and the result is miserable lives for the family.[63]

References

[edit]- ^ Hoffmann, E.T.A (1816). "Nussknacker und Mausekönig" [The Nutcraker and the Mouseking]. Kinder-Mährchen [Children's Stories]. Vol. 1. Berlin: In der Realschulbuchhandlung. p. title page plate after by E.T.A. Hoffmann (precedes page 115). Retrieved 21 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Blamires, David (2009). "13. E. T. A. Hoffmann's Nutcracker and Mouse King". Telling Tales. Cambridge, England: Open Book Publishers. pp. 223–244. Retrieved 11 January 2025 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, E.T.A. (1840). Nussknacker & Mäusekönig, ein allerliebstes Kindermährchen nach E. T. A. Hoffmann oder neueste Bilderlust in X fein illuminirten Kupfertafeln nach Original-Zeichnungen von P. C. Geißler [Nutcracker & Mouse King, a most adorable children's fairy tale after E.T.A. Hoffmann with the latest picture delights in 10 finely illuminated copper plates after original drawings by PC Geißler] (in German). Illustrated by Peter Carl Geissler. Nürnberg, Germany: Zeh. p. Plate II. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ Hoffmann, Ernst Theodor Wilhelm (1929). "The History OF Kralatuk (Translated by William Makepeace Thackeray)". In Melville, Lewis; Hargreaves, Reginald (eds.). Great German Short Stories. London: Boni and Liveright. pp. 513–526. Retrieved 26 January 2025 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Hoffmann, E.T.A. (1892). Nutcracker and Mouse King, and The Educated Cat. Translated by Hope, Ascott R. Illustrated by Bertall. London: T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ Hoffmann, E.T.A. (1919). Nutcracker and Mouse-King. Translated by Browne, E. Gordon. E.T.A. Hoffmann was not acknowledged as original author; Illustrated by Florence Anderson. London: George G. Harrap and Co.

- ^ Saint Simon, Mrs. (1853). Nutcracker and Mouse-King, Translated from the German of Hoffman. Wood engravings by Albert H. Jocelyn. New York: D. Appleton & Company. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffman, Ernst Theodor Wilhelm (1819). Die Serapionsbrüder [The Serapion Brethren]. Vol. I. Translated by Ewing, Major Alex. London: George Bell and Sons (published 1886).

- ^ Hoffmann, E.T.A. F. (1930). The Nutcracker and the Mouse-king. Translated by Encking, Louise F. Illustrated by Emma L. Brock. Chicago: A. Whitman & Co. Retrieved 28 January 2025 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ "Louise Encking Translates Tale of 'Nutcracker'". Star Tribune. Minneapolis, Minnesota. 28 September 1930. p. 52. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ Hoffmann, E.T.A. (1996). The Story of the Nutcracker. Translated by Ewing, Alexander. Adapted by Bob Blaisdell; edited by Candice Ward; illustrated by Thea Kliros. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications (Dover Children's Thrift Classics).

- ^ "Blaisdell, Bob". Encylopedia.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ "Artist's inspiration drawn from classic children's Tales". Poughkeepsie Journal. Poughkeepsie, New York. 29 October 2004. p. 17. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Hoffmann, E. T. A. (2018). The Nutcracker, The Sandman, and other Dark Tales: The Best Weird Tales and Fantasies of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated by Ewing, Alexander; Bealby, J. T. Introduction by M. Grant Kellermeyer; also edited, annotated, and illustrated by him. Fort Wayne, Indiana: Oldstyle Tales Press.

- ^ "Summary Bibliography: M. Grant Kellermeyer". The Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDb). Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ Kellermeyer, Michael Grant. "Illuminating Classic, Literary Horror Through Art & Analysis". Old Style Tales.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2025. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ Hoffmann, E.T.A. (1893). The nutcracker and the Mouse-King. Translated by Bell, Anthea. Illustrated by Lisbeth Zwerger. Natick, MA: Picture Book Studio USA; Distributed by Alphabet Press.

- ^ "Zwerger, Lisbeth 1954–". Encylopedia.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Folkart, Burt A. (September 29, 1992). "Ralph Manheim; Master Translator of Literature". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Steinberg, Michael (11 November 1984). "A Classic. New and Complete: Nutcracker. By E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated by Ralph Manhelm. Illustrated by Maurice Sendak. 102pp. New York: Crown Publishers- $19.95. (Ages 8 and up)". The New York Times. pp. 45 & 63. Retrieved 30 December 2024.

- ^ Goldberg, Robin Lily (December 2009). From Prose to Pointe Shoes: E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” (PDF) (Honors thesis). University of Michigan. p. 46. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Hoffmann, E.T.A.; Dumas, Alexandre (2007). The Nutcracker and the Mouse King [Hoffmann] and The Tale of the Nutcracker [Dumas]. Translation by Joachim Neugroschel and introduction by Jack Zipes. New York: Penguin Books.

- ^ Grimm, Jacob; Grimm, Wilhelm (1916). "King Thrushbeard". The Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. New York: Doubleday. pp. 312–314. Retrieved 12 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tartar, Maria (2020). "Inventing Portal Fantasies: E. T. A. Hoffmann's The Nutcracker and the Mouse King". Marvels & Tales. 34 (1): 24–37. Retrieved 8 January 2025 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Bruning, Peter (March 1955). "E. T. A. Hoffmann and the Philistine". The German Quarterly. 28 (2): 111–121. Retrieved 7 January 2025 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Tatar, Maria Magdalene (May 1971). Romantic "Naturphilosophie" and Psychology: A Study of G.H. Schubert and the Impact of His Works on Heinrich Von Kleist and E.T.A. Hoffmann (PDF) (PhD thesis). Princeton University. pp. 218–219. Retrieved 3 January 2025 – via Proquest.

- ^ a b c Robertson, Ritchie (1992). "Introduction". The golden pot, and other tales. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. vii–xxxii.

- ^ McGlathery, James M. (October 1974). "Review: The Shattered Self: E. T. A. Hoffmann's Tragic Vision. by Horst S. Daemmrich". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 73 (4): 601–603. Retrieved 7 January 2025 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Daemmrich, Horst S. (1873). The Shattered Self: E.T.A. Hoffmann's Tragic Vision. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 55–62 & 117.

- ^ Negus, Kenneth G. (October 1975). "Review: The Shattered Self: E. T. A. Hoffmann's Tragic Vision. by Horst S. Daemmrich". MLN [former Modern Language Notes]. 90 (5): 710–713. Retrieved 7 January 2025 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Scullion, Val; Treby, Marion (2020). "The Romantic Context of ETA Hoffmann's Fairy Tales, The Golden Pot, The Strange Child and The Nutcracker and the Mouse King" (PDF). English Language and Literature Studies. 10 (2): 40–52. Retrieved 7 January 2025 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b c d Zunshine, Lisa (2022). "Why Reasonable Children Don't Think that Nutcracker is Alive or that the Mouse King is Real". In Sha, Richard C.; Faflak, Joel (eds.). Romanticism and Consciousness, Revisited (PDF). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 225–248. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d Roth, Elizabeth Elam (Spring 1997). "Aesthetics of the Balletic Uncanny in Hoffmann's "Nutcracker and Mouse King" and "The Sandman"". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 22 (1): 39–42. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Emer (July 2009). "Cross-cultural development of literary traditions". Comparative Children’s Literature. Translated by Bell, Anthea. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Baum, L. Frank (1901). Dot and Tot of Merryland. Illustrated by W.W. Denslow (1st ed.). Chicago and New York: George M. Hill.

- ^ a b c d Baum, L. Frank (1920). Dot and Tot of Merryland [reprint, scaned copy on line]. Illustrated by W.W. Denslow. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Encking & Brockwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Walker, Adam (2018). "Objects of Nonsense, Anarchy, and Order. Romantic Theology in Lewis Carroll's and George". North Wind: A journal of George MacDonald Studies. 37 (1): Article 1. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ MacDonald, George (1911). The Princess and the Goblin. London: Blackie and Son. p. 51. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann, E.T.A. (1845). Histoire d'un casse-noisette Tome 1 [The Story of the Nutcracker Volume 1] (in French). Illustrated by Bertall. Paris: J. Hetzel. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ a b c Ardizzone, Sarah (24 December 2015). > "The story of The Nutcracker - in pictures". The Guardian. pp. 45 & 63. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1847). The History of a Nutcracker / by Alexandre Dumas with two hundred and twenty illustrations by Bertall (2 Volumes). Translator not identified. Illustrated by Bertall. London: Chapman and Hall. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ a b Munro, Douglas (1978). Alexandre Dumas Père : a bibliography of works translated into English to 1910. New York: Garland Pub. pp. 88–89. Retrieved 5 February 2025.

- ^ Hoffmann, E.T.A. "The History of a Nutcracker". A Picture Story Book with Four Hundred Illustrations. London: G. Routledge & Co. Retrieved 9 February 2025.

- ^ Dumas Père, Alexandre (1976). Nutcracker. Translated by Munro, Douglas. Phillida Gili. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Douglas Munro Alexandre Dumas père Collection, Date range: 1807-1994". University of Manchester Library. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ Dumas Père, Alexandre (2015). The Story of a Nutcracker. Translated by Ardizzone, Sarah. Cover illustrated by Kitty Arden. London: Vintage Publishing.

- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1860). "Histoire d'un casse-noisette" [The Story of the Nutcracker]. Le Nouveau magasin des enfants [The New Children's Periodical] (in French). 4: 1–244. Retrieved 4 February 2025.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Children's Story?was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Pittsburg ballet offers a suite treat". The Baltimore Sun. 26 December 2006. pp. C3. Retrieved 29 January 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Nutcracker". The Marius Petipa Society. Archived from the original on 6 May 2024. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1845). Histoire d'un casse-noisette. Tome 2 [The Story of the Nutcracker Volume 2] (in French). Illustrated by Bertall. Paris: J. Hetzel. Retrieved 10 February 2025.

- ^ "Nussknacker und Mausekönig, Op.46 (Reinecke, Carl)". IMSLP/Petrucci Music Library: Free Public Domain Sheet Music.

- ^ E.T.A. Hoffmann (1876). Nutcracker and Mouse King: A Legend.

- ^ "The Nutcracker Prince". Clear Black Lines. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- ^ Fleming, Adam (November 30, 2011). "Adam Shankman To Helm 'The Nutcracker'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ White, James (December 7, 2009). "The Nutcracker Is Back(er)". Empire Online. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ "Photo Flash: First Look at New Village Arts' West Coast Premiere of THE NUTCRACKER". Broadway World. December 9, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "Nutcracker and Mouseking, TV-Movie (Series), 2015" – via Crew-United.com.

- ^ "The Nutcracker and the Four Realms Press Kit" (PDF). wdsmediafile.com. Walt Disney Studios. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King". KPBS Public Media. 2021-11-19. Retrieved 2022-12-25.

- ^ The Nutcracker and the Mouse King | PBS, retrieved 2022-01-01

- ^ Brower, Alex (December 24, 2023). "Nutcracker retelling spins darker than classic holiday favorite". Asheville Citizen-Times. p. D9.

External links

[edit] Media related to Notropis procne/sandbox6 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Notropis procne/sandbox6 at Wikimedia Commons The full text of the 1853 American edition of Nutcracker and Mouse-King at Wikisource

The full text of the 1853 American edition of Nutcracker and Mouse-King at Wikisource- Illustrated book by Peter Carl Geissler of the Bamberg State Library (in German)

Nutcracker and Mouse King public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Nutcracker and Mouse King public domain audiobook at LibriVox