User:Jacksharpe54/Aphra Behn

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft

[edit]Lead

[edit]Life and work

[edit]Versions of her early life

[edit]

Information regarding Behn's life is scant, especially regarding her early years. This may be due to intentional obscuring on Behn's part. One version of Behn's life tells that she was born to a barber named John Amis and his wife Amy; she is occasionally referred to as Aphra Amis Behn.[1] Another story has Behn born to a couple named Cooper.[1] The Histories and Novels of the Late Ingenious Mrs. Behn (1696) states that Behn was born to Bartholomew Johnson, a barber, and Elizabeth Denham, a wet-nurse.[1][2] Colonel Thomas Colepeper, the only person who claimed to have known her as a child, wrote in Adversaria that she was born at "Sturry or Canterbury"[a] to a Mr Johnson and that she had a sister named Frances.[3] Another contemporary, Anne Finch, wrote that Behn was born in Wye in Kent, the "Daughter to a Barber".[3] In some accounts the profile of her father fits Eaffrey Johnson.[3] ^^^^^ Although not much is known about her early childhood, one of her biographers, Janet Todd, believes that the common religious upbringing at the time could have heavily influenced much of her work. She argued that throughout Behn's writings that her experiences in church were not of religious fervor, but instead chances for her to explore her sexual desires, desires that will later be shown through her plays. In one of her last plays she writes "I have been at the Chapel; and seen so many Beaus, such a Number of Plumeys, I cou'd not tell which I shou'd look on the most...".[4] =====

^^^^^ Education

Although Behn's writings show some form of education, it is not clear how she obtained the education that she did. It was somewhat taboo for women at the time to receive a formal education, Janett Todd notes. Although some aristocratic girls in the past were able to receive some form of education, that was most not likely the case for Aphra Behn based on the time she lived. Self-tuition was practiced by European women during the 17th century, but it relied on the parents to allow that to happen. She most likely spent time copying poems and other writings, which not only inspired her but educated her. It is important to note that Aphra was not alone in her quest of self-tuition during this time period, and there are other notable women such as the first female medical doctor Dorothea Leporin who made efforts to self-educate.[5] In some of her plays, Aphra Behn show's disdain towards this English ideal of not educating women formally. She also, though, seemed to believe that learning Greek and Latin, two of the classical languages at the time, were not as important as many authors thought it to be. She may have been influenced by another writer named Francis Kirkman who also lacked knowledge of Greek or Latin, who said "you shall not find my English, Greek, here; nor hard cramping Words, such as will stop you in the middle of your Story to consider what is meant by them...". Later in life, Aphra would make similar gestures to ideas revolving around formal education.[6] =====

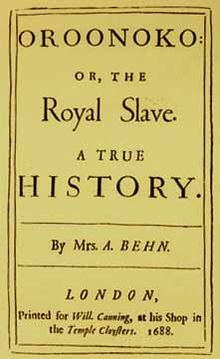

Behn was born during the buildup of the English Civil War, a child of the political tensions of the time. One version of Behn's story has her travelling with a Bartholomew Johnson to the small English colony of Surinam (later captured by the Dutch). He was said to die on the journey, with his wife and children spending some months in the country, though there is no evidence of this.[1][7] During this trip Behn said she met an African slave leader, whose story formed the basis for one of her most famous works, Oroonoko.[1][2] It is possible that she acted a spy in the colony.[3] There is little verifiable evidence to confirm any one story.[1] In Oroonoko Behn gives herself the position of narrator and her first biographer accepted the assumption that Behn was the daughter of the lieutenant general of Surinam, as in the story. There is little evidence that this was the case, and none of her contemporaries acknowledge any aristocratic status.[3][1] There is also no evidence that Oroonoko existed as an actual person or that any such slave revolt, as is featured in the story, really happened.

Writer Germaine Greer has called Behn "a palimpsest; she has scratched herself out," and biographer Janet Todd noted that Behn "has a lethal combination of obscurity, secrecy and staginess which makes her an uneasy fit for any narrative, speculative or factual. She is not so much a woman to be unmasked as an unending combination of masks".[7] It is notable that her name is not mentioned in tax or church records.[7] During her lifetime she was also known as Ann Behn, Mrs Behn, agent 160 and Astrea.[8]

Article body

[edit]References

[edit]References 4,5,6

- ^ a b c d e f g Stiebel, Arlene. "Aphra Behn". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Aphra Behn". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Janet Todd, "Behn, Aphra (1640?–1689)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Todd, Janet (1996). The Secret Life of Aphra Behn. London: Andre Deutsch Limited. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-8135-2455-5.

- ^ Women, education, and agency, 1600-2000. Jean Spence, Sarah Jane Aiston, Maureen M. Meikle. New York: Routledge. 2010. ISBN 978-0-415-99005-9. OCLC 298467847.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Todd, Janet (1996). The Secret Life of Aphra Behn. London: Andre Deutsch Limited. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-8135-2455-5.

- ^ a b c Derek Hughes; Janet Todd, eds. (2004). The Cambridge Companion to Aphra Behn. Cambridge University. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0521527200.

- ^ Todd, Janet (2013) The Secret Life of Aphra Behn; Rutgers University Press; ISBN 978-0813524559

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).