User:DJ Cane/Kennewick

This sandbox page by DJ Cane is for a major restructuring of the article for Kennewick, Washington that has been completed and does not reflect the current revision.

Kennewick, Washington | |

|---|---|

| City of Kennewick | |

An areal view of Kennewick taken from above the Columbia River near the Blue Bridge. | |

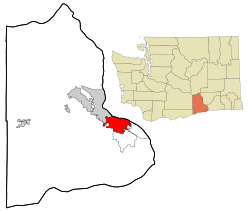

Location of Kennewick, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°12′13″N 119°9′33″W / 46.20361°N 119.15917°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Benton |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Don Britain[1] |

| • City manager | Marie Mosley[2] |

| Area | |

• City | 28.84 sq mi (74.70 km2) |

| • Land | 27.45 sq mi (71.09 km2) |

| • Water | 1.39 sq mi (3.61 km2) |

| Elevation | 407 ft (124 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 73,917 |

• Estimate (2018)[5] | 82,943 |

| • Rank | US: 411st WA: 14th |

| • Density | 2,973.04/sq mi (1,147.88/km2) |

| • Urban | 232,954 (US: 171st) |

| • Metro | 296,224 (US: 164th) |

| • Tri-Cities | 357,146 (US: 103rd) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 99336–99338 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-35275 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512347[6] |

| Website | www.go2kennewick.com |

Kennewick (/ˈkɛnəwɪk/) is a city in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington, along the southwest bank of the Columbia River, just southeast of the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima rivers and across from the confluence of the Columbia and the Snake River. It is the most populous of the three cities collectively referred to as the Tri-Cities (the others being Pasco and Richland). The population was 73,917 at the 2010 census. July 1, 2018 estimates from the Census Bureau put the city's population at 82,943.[7] The 2018 population estimate for the Tri-Cities metro area is 296,224, making it the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the state.[8]

The discovery of Kennewick Man along the banks of the river demonstrates human habitation of the area by Native Americans for at least 9,000 years.[9] American settlers began moving into the area in the late-19th Century as transportation infrastructure was built to connect Kennewick to other settlements along the Columbia River. The city's growth was accelerated by the construction of the Hanford Site at Richland as workers from around the country came to participate in the Manhattan Project. Hanford and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory continue to be major sources of employment.[10] The city's economy has diversified over time and now hosts offices for Amazon and Lamb Weston.[11][12]

History

[edit]Native Peoples

[edit]Native Americans populated the area around Kennewick for millennia before being discovered and settled by Americans who descended from Europeans. Kennewick's low elevation helps to moderate winter temperatures. On top of this, the city's riverside location made salmon and other river fish easily accessible. By the 19th Century, people lived in and between two major camps in the area. These were located near present day Sacajawea State Park in Pasco and Columbia Point in Richland. Lewis and Clark noted that there were many people living in the area when they passed through in 1805 and 1806.[13]

There are conflicting stories on how Kennewick gained its name, most attributing it in some form or another to the Native Americans living in the area. Some reports claim that the name to come from a native word meaning "grassy place".[14] It has also been called "winter paradise," mostly because of the mild winters in the area. In the past, Kennewick has also been known by other names. Legend has it that the strangest was "Tehe," which has been attributed to the reaction from a native girl's laughter when asked the name of the region. This seems to be corroborated by early letters sent to the area with the city listed as Tehe, Washington. Other reports claim that the city's name is derived from how locals pronounced the name Chenoythe, who was a member of the Hudson's Bay Company.[15]

Settlement and early-20th Century

[edit]

The land Kennewick stands on was ceded by the Umatilla and Yakama Tribes at the Walla Walla Council in 1855.[16] Ranchers began working with cattle and horses in the area as early as the 1860s, but in general settlement was slow due to the arid climate. The first non-Native settlement in the area was Ainsworth, which was where US 12 crosses the Snake River between Pasco and Burbank today. Some Ainsworth residents would commute to what is now Kennewick via small boats for work. All that remains to show the location of Ainsworth today is a marker placed by the Washington State Department of Transportation near the site.[17]

During the 1880s, steamboats and railroads connected what would become known as Kennewick to the other settlements along the Columbia River.[13] In 1887, a temporary railroad bridge was constructed by the Northern Pacific Railroad connecting Kennewick and Pasco. That bridge could not endure the winter ice on the Columbia and was partially swept away in the first winter. A new, more permanent bridge was built in its place in 1888. Until this time, rail freight from Minneapolis to Tacoma had to cross the Columbia River via ferry.[18] It was around this time that a town plan was first laid out, centered around the needs of the railroad. A school was constructed using donated funds, but this burned soon after it was finished. This initial boom only lasted briefly, as most of the people who came to Kennewick left after the bridge was finished.[15]

In the 1890s, the Northern Pacific Irrigation Company installed pumps and ditches to bring water for agriculture into the Kennewick Highlands. Once there was a reliable water source, orchards and vineyards were developed all over the Kennewick area. Strawberries were another successful crop.[19] The turn of the century saw the creation of the city's first newspaper, the Columbia Courier. Kennewick was officially incorporated on February 5, 1904. and the name of the newspaper changed to the Kennewick Courier in 1905 to reflect this change.[20] In the following decade, there was an unsuccessful bid to move the seat of Benton County from Prosser to Kennewick. There have been other unsuccessful attempts to make this move throughout the city's history, most recently in 2010.[21][22]

In 1915, Kennewick was connected to the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River with the opening of the Celilo Canal. City residents hoped to capitalize on this new infrastructure by forming the Port of Kennewick, making the city an inland seaport. Freight and passenger ship traffic began that year. The port also developed rail facilities in the area.[23] Transportation through the region further improved with construction of the Pasco-Kennewick Bridge in 1922, locally known as the Green Bridge. This connected the two cities for vehicle traffic for the first time.[24][25] Richland continued to be small and geographically removed, but Kennewick and Pasco both experienced decent growth and became informally known as the Twin Cities throughout the Columbia Basin because of their juxtaposition across the river from each other.

Like many other agricultural communities, the Great Depression had an impact in Kennewick. Despite lowered prices for crops grown in the region, the city continued to experience growth, gaining another 400 people during the 1930s. Growth was aided by federal projects that improved the Columbia River. Downstream, Bonneville Dam at Cascade Locks, Oregon allowed larger barges to reach Kennewick. Grand Coulee Dam, located upstream of Kennewick, fostered irrigation across the Columbia Basin north of Pasco, sending more raw material through Kennewick.[13]

Hanford boom

[edit]

Kennewick and the greater Tri-Cities area experienced significant changes during World War II. In 1943, the United States opened the Hanford nuclear site in and north of Richland. Its purpose originally was to help produce nuclear weaponry, which the US was trying to develop. People came from across the United States to work at Hanford, not knowing what they were actually producing. They were only told that their work would help the war effort.[26] The federal government constructed housing in Richland, but many employees of that site then commuted from Kennewick. The plutonium refined there was used in the Fat Man bomb used to attack Nagasaki in 1945 in the decisive final blow of the war. As the Hanford Site's purpose has evolved, there has continually been a tremendous influence from the site on the workforce and economy of Kennewick.[27][10] Because of activity at the Hanford Site, 1950 Census was the first one to record Richland as being the largest city in the Tri-Cities. Prior to this, Richland had only a few hundred people. Pasco was the largest with nearly 4,000 residents and Kennewick had about half that.

An effort to build a new bridge began in 1949 and was funded in 1951. Traffic between Kennewick and Pasco, largely due to commuters heading to and from the Hanford Site in Richland and McNary Dam, which was under construction near Umatilla, Oregon. The two-lane Green Bridge was the only one for automobiles across the Columbia River in the Tri-Cities at the time, and the 10,000 cars crossing it daily had created traffic problems. The new bridge, dubbed the Blue Bridge, was a four-lane divided highway and opened in 1954 less than 2 miles (3.2 km) upstream of the Green Bridge.[28] The Cable Bridge was opened between Kennewick and Pasco in 1978. Rather than supplementing the Green Bridge as the Blue Bridge did, the Cable Bridge was built to replace it. The Green Bridge was slated for demolition, but this proved to be controversial. Those seeking to preserve the bridge for historical reasons were able to stall the demolition, but it was eventually torn down in 1990.[29]

Racial discrimination against African Americans was common in Kennewick before the Civil Rights movement. The city was a sundown town, requiring African Americans to be out of the city after nightfall. The only place these people could live in the Tri-Cities at the time was east Pasco. Even during the day, African Americans would experience harassment by the general public and police. In 1963, the Washington State Board Against Discrimination indicted Kennewick its sundown town policy.[30][31]

The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens caused several inches of volcanic ash to fall on Kennewick. Higher accumulations were recorded in Yakima and Ritzville, but the ash plume was thick enough to trigger street lamps to turn on at noon. Cars that didn't have external filters stopped functioning during the eruption, and it took several months to completely clean all the ash.[32][33] Kennewick and surrounding areas have been dusted by smaller eruptions of Mount St. Helens since.[34]

The 1980s also brought the two most serious attempts to merge Kennewick with the other cities in the Tri-Cities, both of which failed. This resulted from an economic downtown in the area caused by the cancellation of two proposed nuclear power plants on the Hanford Site. The first proposal was to consolidate all three cities (Kennewick, Pasco, and Richland) into one, while the second only included Kennewick and Richland. Support for both of these attempts was strong in Richland, but voters in Kennewick and Pasco were not on board.[35]

1990 to Present

[edit]The Toyota Center was used as a venue for ice hockey and figure skating during the 1990 Goodwill Games.[36] This international sporting competition was similar to the Olympic Games, but significantly smaller in scale. Most of the events were held in the host city, Seattle, but other Washington cities like Tacoma and Spokane also had venues used for the event.[37]

In 1996, an ancient human skeleton was found on a bank of the Columbia River. Known as Kennewick Man, the remains are notable for their age (some 9,300 years). Ownership of the bones has been a matter of great controversy. After court litigation, a group of researchers were allowed to study the remains and perform various tests and analyses. They published their results in a book in 2014. A 2015 genetic analysis confirmed that this ancient skeleton was ancestral to Native Americans of the area (some observers had contended that the remains were of European origin.) The genetic analysis has notably contributed to knowledge about the peopling of the Americas.[38]

Kennewick fared better than most of the state during the Great Recession, which is primarily due to consistent job growth in the metro area during that period. Home sales did experience a small decline from 2007 to 2009, but rebounded in 2010.[39] Layoffs at Hanford in 2011 caused some uncertainty in the economy, but this was only short lived.[40] Since the recession, Kennewick has expanded greatly. While growth has been experienced throughout the city, new development has been strongest in the Southridge area along US 395 and in the west part of the city.[41]

Geography

[edit]

Kennewick is located in Eastern Washington along the south side of the Columbia River and is one of three cities in the Tri-Cities. The other two cities are Richland, which is upstream of Kennewick on the same side of the river, and Pasco, which is across the river. The elevation within the city rises from the river to a line of ridges on the south side of town that result from the same anticline that created Badger Mountain and Rattlesnake Mountain.[42] Beyond that line of ridges, the city slopes up toward the Horse Heaven Hills.[43] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 28.36 square miles (73.45 km2), of which, 26.93 square miles (69.75 km2) is land and 1.43 square miles (3.70 km2) is water.[44]

The city overlies basalt laid down by the Columbia River Basalt Group, which was a type of volcanic eruption known as a flood basalt. This erupted from fissures that were geographically spread throughout eastern Washington, eastern Oregon, and far western Idaho. Most of the lava erupted between 17 and 14 million years ago, with smaller eruptions lasting to 6 million years ago.[45] The nearest eruptive vent to Kennewick from this period is near Ice Harbor Dam along the Snake River upstream of Burbank and Pasco.[46] While outcroppings from the basalt flows can be seen throughout Kennewick, they are mostly buried by sediments.

The first major sediment deposit following the eruptions is the Ringold Formation, which was placed by the Columbia River between 8 and 3 million years ago. Further deposition came as a result of the Missoula Floods.[42] At the end of the last glacial maximum, an ice dam blocked the Clark Fork River in Montana. The pressure from the resulting lake would periodically build to the point that the dam would fail, sending massive amounts of water cascading to the Pacific Ocean.[47] The flood's movement was impeded by the Horse Heaven Hills, creating a temporary lake known as Lake Lewis. This abrupt halt in flow allowed the floodwater to drop a significant amount of sediment before passing through Wallula Gap toward Hermiston. During the largest floods, the water's surface reached 1,250 feet (380 m) above sea level. This completely covered all of the land within Kennewick's city limits.[48]

Earthquakes are a hazard in Kennewick, though not to the same extent or frequency as areas west of the Cascade Range like the Puget Sound Region. The entire Pacific Northwest is threatened with subduction zone earthquakes, which can exceed magnitudes of 9. The last of these earthquakes, which are similar to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake in Japan, occurred in 1700.[49] Damage is expected to be minimal in and around Kennewick, but destruction west of the Cascades could have a major impact of the economy of inland areas. These subduction zone earthquakes will be centered on the boundary between the North American Plate and the Juan de Fuca Plate, which is located offshore.[50] Fault lines closer to Kennewick also produce earthquakes. While these are weaker, they can still cause damage. One such earthquake, named the 1936 State Line earthquake, occurred near Walla Walla with damage extending as far away as Prosser.[51]

Climate

[edit]

Kennewick has a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk), that closely borders on a desert climate (Köppen BWk) owing to its position east of the Cascade Mountains.[52] The Cascades create an effective rain shadow, causing Kennewick to receive a fraction of the precipitation that cities east of the mountains like Portland and Seattle get annually, with values being more similar to that of Phoenix, Arizona. The mountains also insulate Kennewick from the moderating effects of the Pacific Ocean, allowing the city to experience more extreme temperatures than points west.[53][54]

Before McNary Dam was built on the Columbia River downstream of Kennewick, the river would periodically flood. The worst of these floods happened in 1948 and caused $50 million ($533.6 million in 2019) worth of damage and one death.[55] The government responded by building the McNary Levee System to protect lower parts of town.[56] Floods like this were the result of melting snow, and were most extreme when a heavy snowpack developed in the mountains over winter followed by a strong regional heatwave. The flood threat from the Columbia has significantly decreased since dams were built.[57] Zintel Canyon Dam located near the Southridge Sports and Events Complex was built to protect parts of the city from a 100-year flood. While the creek that flows through Zintel Canyon typically runs dry, summer thunderstorms in the Horse Heaven Hills can generate destructive flash floods.[58]

Laying at the bottom of a basin, temperature inversions can develop, creating dense fog and low clouds in Kennewick. This is particularly common in the winter and can last for several days. Inversions form during periods of high pressure. High pressure combining with the low angle of the sun in winter brings stability in the atmosphere, allowing denser cold air to sink to the floor of the Columbia Basin. Pollutants will also become trapped, lowering the air quality. When fog develops during an inversion, it will often limit diurnal temperature changes to just a few degrees. Temperatures in areas above the inversion will often be warmer despite being at a higher elevation.[59] These inversions cause a major decrease in the amount of sunshine Kennewick receives annually.[60] If a weather system drops precipitation, but isn't strong enough to clear the inversion, freezing rain or sleet can fall in Kennewick.[61]

The average annual wind speed in Kennewick is 8 miles per hour (13 km/h), but strong winds are a common occurrence in Kennewick and can sometimes cause damage.[62] Wind and the arid nature of the region can cause dust storms. These events can happen any time of year, but this issue is most common in the spring and fall months when farms in the region have high amounts of exposed soil.[63] Chinook winds can also be experienced during the winter. These are formed when moisture gets removed from air moving across the Cascade Mountains, allowing the air to warm significantly as it descends into the Yakima Valley and Columbia Basin. Many of the high temperature records set during the winter months result from Chinook events.[64][65]

Summer brings extreme heat and low humidity, which are ideal conditions for wildfires in undeveloped areas adjacent to town. One such fire in 2018 started along Interstate 82 south of Kennewick and burned 5,000 acres (2,000 ha), destroying five homes on the edge of Kennewick.[66] While rare, severe thunderstorms can also cause damage in Kennewick. Severe storms can produce damaging wind, hail, lightning, and weak tornadoes. No tornadoes were recorded in Kennewick between 1962 and 2011, but one did touch down in 2016.[67][68]

| Climate data for Kennewick, Washington, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1894–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

74 (23) |

87 (31) |

95 (35) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

115 (46) |

115 (46) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

79 (26) |

71 (22) |

115 (46) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

63 (17) |

71 (22) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

98 (37) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

93 (34) |

80 (27) |

68 (20) |

58 (14) |

104 (40) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 41.8 (5.4) |

48.3 (9.1) |

58.7 (14.8) |

66.6 (19.2) |

74.8 (23.8) |

81.9 (27.7) |

90.5 (32.5) |

89.6 (32.0) |

80.1 (26.7) |

66.1 (18.9) |

50.9 (10.5) |

40.1 (4.5) |

65.7 (18.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 35.5 (1.9) |

39.3 (4.1) |

47.4 (8.6) |

54.2 (12.3) |

61.9 (16.6) |

68.8 (20.4) |

75.9 (24.4) |

75.0 (23.9) |

66.0 (18.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.0 (6.1) |

34.3 (1.3) |

54.6 (12.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 29.2 (−1.6) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

36.1 (2.3) |

42.0 (5.6) |

49.1 (9.5) |

55.8 (13.2) |

61.4 (16.3) |

60.5 (15.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

41.8 (5.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

43.5 (6.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16 (−9) |

17 (−8) |

26 (−3) |

33 (1) |

39 (4) |

47 (8) |

53 (12) |

52 (11) |

42 (6) |

29 (−2) |

22 (−6) |

14 (−10) |

8 (−13) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−23 (−31) |

8 (−13) |

18 (−8) |

26 (−3) |

35 (2) |

38 (3) |

37 (3) |

21 (−6) |

14 (−10) |

−8 (−22) |

−22 (−30) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.08 (27) |

0.77 (20) |

0.73 (19) |

0.56 (14) |

0.64 (16) |

0.49 (12) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.18 (4.6) |

0.30 (7.6) |

0.58 (15) |

0.99 (25) |

1.16 (29) |

7.67 (195) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.4 (11) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

2.2 (5.6) |

8.1 (20.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 11 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 74 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 inch) | 1.8 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 3.5 |

| Source 1: [69] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Snowfall data for the Tri-Cities Airport in Pasco.[70] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 183 | — | |

| 1910 | 1,219 | 566.1% | |

| 1920 | 1,684 | 38.1% | |

| 1930 | 1,519 | −9.8% | |

| 1940 | 1,918 | 26.3% | |

| 1950 | 10,106 | 426.9% | |

| 1960 | 14,244 | 40.9% | |

| 1970 | 15,212 | 6.8% | |

| 1980 | 34,397 | 126.1% | |

| 1990 | 42,155 | 22.6% | |

| 2000 | 54,693 | 29.7% | |

| 2010 | 73,917 | 35.1% | |

| 2018 (est.) | 82,943 | [5] | 12.2% |

| source:[71] 2018 Estimate[73] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[4] of 2010, there were 73,917 people, 27,266 households, and 18,528 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,744.8 inhabitants per square mile (1,059.8/km2). There were 28,507 housing units at an average density of 1,058.6 per square mile (408.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.5% White, 1.7% African American, 0.8% Native American, 2.4% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 12.1% from other races, and 4.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 24.2% of the population.

There were 27,266 households of which 37.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.3% were married couples living together, 13.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 32.0% were non-families. 25.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.67 and the average family size was 3.22.

The median age in the city was 32.6 years. 28.2% of residents were under the age of 18; 10.3% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.8% were from 25 to 44; 23.8% were from 45 to 64; and 10.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.9% male and 50.1% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, there were 54,693 people, 20,786 households, and 14,176 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,384.9 people per square mile (920.9/km²). There were 22,043 housing units at an average density of 961.2 per square mile (371.2/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 82.93% White, 1.14% Black or African American, 0.93% Native American, 2.12% Asian, 0.11% Pacific Islander, 9.4% from other races, and 3.37% from two or more races. 15.55% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race. 18.2% were of German, 9.6% English, 8.5% Irish and 8.5% American ancestry. 84.6% spoke English and 12.5% Spanish as their first language.

There were 20,786 households out of which 37.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.5% were married couples living together, 12.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.8% were non-families. 26.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.6 and the average family size was 3.15.

In the city, the population was spread out with 29.6% under the age of 18, 10.3% from 18 to 24, 29.3% from 25 to 44, 20.6% from 45 to 64, and 10.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $41,213, and the median income for a family was $50,011. Males had a median income of $41,589 versus $26,022 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,152. About 9.7% of families and 12.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.8% of those under age 18 and 8.7% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]

Kennewick's economy is closely tied to the rest of the Tri-Cities and is heavily influenced by the Hanford Site and the national laboratory. The agriculture and healthcare industries also employ many residents.[74] It has developed to become the retail hub of the Tri-Cities and hosts the only mall in the area - Columbia Center Mall.[13] As such, Kennewick draws in shoppers from a significant portion of southeast Washington and northeast Oregon.[75] Aside from the commercial area around the mall, the other significant retail districts include the historic downtown area and the newly developed Southridge district.[76][77]

Many agricultural commodities are grown near Kennewick, and many of these pass through the city to be processed and/or transported to other markets for consumption. Boise, Idaho based Lamb Weston, a division of ConAgra Foods has corporate offices in Kennewick, and Tyson Foods does processing in town.[74] Volcanic ash is mixed in with the rich soil of the region, creating ideal growing conditions for numerous crops.[78] Irrigation has further enhanced the region, further diversifying the product coming from the Columbia Basin. Higher elevations, like much of the Horse Heaven Hills, don't have access to irrigation water. This limits agricultural activities to ranching and growing wheat.[13][79]

The region is experiencing consistent job growth, which is creating a large population boom. Home prices have increased by about 10% annually in Kennewick for the past several years, with slower increases having occurred before 2016.[75] Despite this growth, unemployment remains above both the national and state averages.[80] Recently, industrial growth in Hermiston and at the Port of Morrow in Boardman has led to an increase in the number of residents who commute to those areas for work.[81] This is further enhanced by a housing shortage in northeast Oregon.[82][83]

Culture

[edit]

Kennewick hosts a number of events throughout the year. During the warm season, many of these are outdoors in public parks.[84] The most significant of these is the Tri-Cities Water Follies, which fill the weekend of the HAPO Gold Cup, a hydroplane race taking place every July in the Columbia River just upstream of the Blue Bridge. Activities in Kennewick that weekend include the races itself as well as an airshow. There are other events throughout the Tri-Cities during Water Follies, such as Art in the Park, a craft show at Howard Amon Park in Richland.[85][86] Over 70,000 people attend events related to Water Follies each year.[87]

Benton and Franklin Counties combine together to host a single fair at the end of each summer at the fairgrounds off SR 397 in east Kennewick. Like many other county fairs across the United States, the fair has livestock exhibitions, retail, carnival rides, and concerts.[88] Also on site during the fair is a rodeo named the Horse Heaven Round-Up.[89]

Tourism

[edit]The arid climate and warm temperatures during the summer draw people to Kennewick from around the Pacific Northwest. Many summertime visitors engage in boating and other water related acrivities in the Columbia, Snake, and Yakima Rivers.[90] The city and port district are working together to further develop tourism throughout the city. This includes recent improvements to Clover Island, which has a hotel, lighthouse, and the Ice Harbor Brewing Company.[91][92][93] Adjacent to Clover Island is historic downtown, which has many antique and clothing shops. Work is ongoing to develop the former Vista Field area in the west side of town into a mixed-use development that will include shopping.[94]

Kennewick lies near the center of Washington's wine country, which stretches from the Yakima Valley through the Columbia Basin and Horse Heaven Hills east to the Walla Walla Valley. There are several American Viticultural Areas near town. Wine tasting is a major part of the Tri-Cities tourism economy, with over 300 wineries and wine bars rooms in the area.[95] The city actively markets this to bring in visitors.[96] Cruises travel up the Columbia from Portland with a stop in the Tri-Cities to tour wineries in the area.[97]

Sports

[edit]| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Founded | Titles | Record Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tri-City Americans | Hockey | WHL | Toyota Center (5,694) | 1988 | 0 | 6,053 |

| Tri-Cities Fire | Indoor American football | AWFC | Toyota Center (6,000) | 2019 | 0 | - |

Kennewick hosts two professional sports teams, the Western Hockey League's Tri-City Americans and Tri-Cities Fire of the American West Football Conference. Both teams play at the Toyota Center.[98][99] The other significant professional sports team in the Tri-Cities, the Tri-City Dust Devils (associated with the San Diego Padres) plays at Gesa Stadium in Pasco.[100]

The Tri-City Americans were one of the original teams in the Western Hockey League, starting in Calgary, Alberta in 1966. The team moved a couple times before coming to the Tri-Cities in 1988, most recently being in a suburb of Vancouver, British Columbia. The team's move to the Tri-Cities made them the first professional hockey team to play in the area and was the catalyst for constructing the Toyota Center.[101] The Americans have won the US Division four times, but have not yet won a Western Conference final.

The Tri-Cities Fire are an indoor football team playing in a league with three other teams. The team was founded in 2019, bringing indoor football back to the Toyota Center after the Tri-City Fever went dormant in 2016.[102][103] The Fire finished their first season with an 0-12 record, the worst in the league.[104] The Fever won one National Indoor Football League championship in 2005, beating the Rome Renegades. They went to the Indoor Football League campionship game in 2011 and 2012, losing to Sioux Falls Storm both years.[105]

While Kennewick does not currently host a professional baseball team, they have a long history of doing so in the past. Professional minor league teams have played in Kennewick starting as early as 1950 with the Tri-City Braves. Other teams included the Tri-City Atoms, the Tri-City A's, the Tri-City Triplets, and the Tri-City Ports. All of these played at Sanders-Jacobs Field, which has since been demolished.[106] The city presently hosts the Atomic City Rollergirls, an amateur roller derby team.[107] Washington State University occasionally plays basketball at the Toyota Center.[108]

Parks and Recreation

[edit]

Kennewick's low precipitation values and mild-to-warm weather provide opportunities for outdoor recreation throughout much of the year. The city's Parks and Recreation Department operates 27 parks plus other facilities for the public to use. Many parks have shelters that can be reserved for events, with most of them offering playgrounds.[109] There are three athletic complexes throughout the city as well.[110] The Parks and Recreation Department also maintains several hiking and bike trails in the city, including the portion of the Sacagawea Heritage Trail that passes through Kennewick.[111]

The largest park in the city's system is Columbia Park, which is a riverfront area to the north of SR 240 from the Richland/Kennewick city line in the west to the Blue Bridge in the east. There are several boat launches here offering access to the Columbia River. Kayaking and canoeing is another popular water activity. The Sacagawea Heritage Trail, a bike path connecting all three of the Tri-Cities, passes through the entire length of the park. The most developed portion of the park is the east end, which has a veterans memorial, golf course, fishing pond, and a large playground.[112] Columbia Park hosts the HAPO Gold Cup, an annual hydroplane race.[113] The part of Richland adjacent to the park is Columbia Park West. Combined, the two form 450 acres (180 ha) of contiguous public recreation land along the river.[114][115]

In the early 2010s, the city built the 52 acres (21 ha) Southridge Sports and Events Complex in the quickly growing south end of town along US 395.[116] This property is primarily used for scheduled sporting events, such as baseball, basketball, and volleyball. That said, it also has recreational facilities that don't need to be reserved, such as a playground and open fields.[117] Kennewick was able to secure a piece of the World Trade Center from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which was placed in the southeast corner of the complex as a memorial to the victims of the September 11 attacks in 2001.[118] The complex was considered complete when the historic carousel that the city restored was opened on the site.[119]

Government

[edit]Kennewick was organized under Title 35A [120] RCW (Revised Code of Washington) as a Code City [121] which provides the basic statutory home rule authority in specifically-granted matters of local concern. The City of Kennewick operates under the council-manager form of government. The city council has seven members, four of which are elected at-large while three are elected by the city's three electorial wards.[122] The mayor is selected by the council members. Kennewick's City Manager serves under the direction of the City Council, and administers and coordinates the delivery of municipal services.

The City of Kennewick is a full-service city, providing police, fire prevention and suppression, emergency medical response, water and sewer, parks, public works, planning and zoning, street maintenance, code enforcement, and general administrative services to residents. The city also operations a regional convention center. [123] According to the City’s 2018 audited financial report, the cities total annual expenses are $96.6 million, of which $24.2 million is funded by Sales Tax, $13.1 million by Utility Tax and $13.0 million by Property Tax.[124]

The citizens of Kennewick are represented in the Washington Senate by Sharon Brown in District 8, and Maureen Walsh in District 16, and in the Washington House of Representatives by Brad Klippert and Matt Boehnke in District 8, and Bill Jenkin and Skyler Rude in District 16[125]. At the national level, Kennewick is part of Washington's US Congressional 4th District, currently represented by Republican Dan Newhouse.

Education

[edit]Out of the city's residents who are 25 years or older, 88% hold a high school diploma (or it's equivalent) with 24% holding a bachelor's degree or better. These rates are higher than Pasco, but lower than Richland.[126] Kennewick does not have any colleges or universities, though many people in town seeking a degree attend Columbia Basin College in Pasco or Washington State University Tri-Cities in Richland.

Public schools located in the city are part of the Kennewick School District (KSD). The Kennewick School District has 17 elementary schools, five middle schools, three high schools serving over 18,000 students.[127] A vocational school is operated by KSD and with funding also coming from other local school districts, named the Tri-Tech Skills Center. Vocational programs at Tri-Tech firefighting, radio broadcasting, and auto body technology.[128] Similarly, KSD contributes funding to Delta High School in Pasco, which is a STEM-focused school drawing students from around the Tri-Cities. KSD also operates Neil F. Lampson Stadium, located at Kennewick High School, which is used to host football and soccer games for the three high schools in town as well as for special events.[129] Lampson Stadium has a capacity of 6,800 people.[130]

There are five private schools for educating children in Kennewick. Many of these are run by Christian churches, with the largest being St. Joseph's Catholic School. Cumulatively, less than 1,000 students are enrolled in private schools in the city.[131]

Media

[edit]The only daily newspaper published in the Tri-Cities, the Tri-City Herald, is based in downtown Kennewick.[132] The Tri-Cities Journal of Business is a monthly print publication that is also located in Kennewick and also has a significant online presence. The Journal of Business also publishes the Senior Times, whose target demographic is Tri-Citians who are 60 years or older.[133][134] The city hosts Tú Decides, a bilingual weekly news publication that is both in print and online. Tú Decudes is available in both Spanish and English.[135] Richland based Tumbleweird is an alternative newspaper published monthly that covers the Tri-Cities.[136]

Kennewick and the Tri-Cities share a television market with Yakima. Because of this, the local affiliates of major national networks are closely linked to the affiliates in Yakima. The studios of the Tri-Cities affiliates of NBC, ABC, and Fox are located in Kennewick. These are KNDU, KVEW, and KFFX respectively.[137][138][139] The CBS affiliate, KEPR is in Pasco.[140] KFFX does not produce any local programming, instead getting its news from KNDU and its parent station - KHQ in Spokane. Unlike the television market, the Tri-Cities and Yakima have separate radio markets. Sixteen radio stations are licensed in Kennewick by the FCC with others in nearby cities. There are several religious non-commercial radio stations with coverage in Kennewick. The school district operates a student-run station out of Tri-Tech.[141] NPR member stations Northwest Public Radio and Oregon Public Broadcasting also serve Kennewick.[142][143]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]

The nearest commercial airport is the Tri-Cities Airport in Pasco with flights to several major international airports in the western part of the country. The busiest route is between Pasco and Seattle-Tacoma.[144] Pasco also has the station for both Amtrak's Empire Builder and Greyhound Lines.[145][146] The Port of Kennewick formerly operated Vista Field near the Toyota Center as a general avaition airport, but it closed at the end of 2013. The port plans to turn the land into a mixed-use development.[147]

Interstate 82 bypasses Kennewick to the south, connecting to Seattle via Interstate 90 and both Portland and Salt Lake City via Interstate 84. US 395 passes through town from south to north connecting to Spokane, also via Interstate 90. State Route 240 and State Route 397 also pass through Kennewick, but these mostly serve local traffic. SR 240 continues northwest to Richland before passing through the Hanford Site. SR 397 connects both Interstate 82 and Interstate 182 to Finley, providing a direct route for freight to go to a chemical plant there.[148]

Public transportation in Kennewick is provided by Ben Franklin Transit, which runs several bus routes. There are both intra-city routes as well as routes connecting to Pasco and Richland. There are two transit centers in Kennewick, the Three Rivers Transit Center near the Toyota Center and the Dayton Transfer Point downtown.[149] The transit authority also operates a dial-a-ride service for disabled persons.[150]

Utilities

[edit]Water and sever services are provided by the city, with electricity coming from Benton Public Utility District. Natural gas comes from Cascade Natural Gas. Kennewick contracts with Waste Management for garbage and recycling collection. Many people use irrigation water sourced from nearby rivers to water their lawns. This system is separate from the water provided by the city. Most of Kennewick is part of the Kennewick Irrigation District, with parts of the east side of town being under the Columbia Irrigation District.[151]

Nearly 80% of Kennewick's energy is hydroelectric, with another 10% coming from nuclear. Altogether, less than 5% of the city's electricity is sourced from fossil fuels.[152]

Health care

[edit]The only hospital in Kennewick is Trios, located in the Southridge area. Trios is a rebranding of Kennewick General Hospital, and still operates the original hospital near downtown. Trios also operates clinics and urgent care facilities throughout the Tri-Cities.[153] The main Trios Hospital has 111 beds for treating patients. Having many clinics around the Tri-Cities, Kadlec Regional Medical Center in Richland is another major health care player in Kennewick. Kadlec has 270 beds to treat patients.[154]

Trios is a Level III trauma center and is the only hospital in the Tri-Cities that is a designated as a pediatric trauma center.[155] Kadlec is a Level II trauma center and often receives victims from car accidents.[156] Patients needing further care are often transported to Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, which is the only Level I trauma center in the Pacific Northwest.[157] Children with significant medical needs are often treated at Seattle Children's. Seattle Children's operates a clinic in Richland.[158]

Notable people

[edit]- Adelle August, actress and 1952 Miss Washington USA[159]

- Stu Barnes, former Tri-City Americans and NHL player, now an assistant coach with the Dallas Stars[160]

- Jeremy Bonderman, Major League Baseball pitcher, Detroit Tigers[161]

- Adam Carriker, defensive end for the Washington Redskins of the National Football League and graduate of Kennewick High School[162]

- Rick Emerson, former radio personality[163]

- Janet Krupin, actress, singer, writer, and producer[164]

- Olaf Kolzig, former Tri-City Americans and NHL goaltender, Washington Capitals[165]

- Damon Lusk, NASCAR driver[166]

- Ray Mansfield, National Football League player, center, Pittsburgh Steelers[167]

- Michael McShane, United States Judge for the District of Oregon[168]

- Leilani Mitchell, Professional basketball player[169]

- Scot Pollard, retired NBA player[170]

- Mike Reilly, NFL quarterback, Pittsburgh Steelers, Green Bay Packers, St. Louis Rams, CFL quarterback, Edmonton Eskimos[171]

- Russ Swan, Major League Baseball pitcher, San Francisco Giants, Seattle Mariners, Cleveland Indians[172]

- Shawn O'Malley, Major League Baseball outfielder, Seattle Mariners[173]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "City Council". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "City Manager". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018 - United States -- Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ Stafford, Thomas W. (2014). "Chronology of the Kennewick Man skeleton (chapter 5)". In Douglas W. Owsley; Richard L. Jantz (eds.). Kennewick Man, The Scientific Investigation of an Ancient American Skeleton. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-62349-200-7.

- ^ a b "In strange twist, Hanford cleanup creates latest boom". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ "Amazon looking to fill 100 jobs at Kennewick job fair". Tri-City Herald. May 10, 2016. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ "Lamb Weston Opens Expanded Operations in Richland, WA". Lamb Weston. October 16, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Jim Kershner (March 2, 2008). "Kennewick — Thumbnail History". Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ Majors, Harry M. (1975). Exploring Washington. Van Winkle Publishing Co. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-918664-00-6.

- ^ a b R. E. Read (February 19, 1950). "Brief history of Kennewick up to 1909". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ Hanford Reach of the Columbia River. National Park Service. 1992.

- ^ "Roadside Markers of Washington". Explore Washington. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "First trains cross the Northern Pacific Railroad bridge spanning the Columbia River between Pasco and Kennewick on December 3, 1887.", History Link; Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ Gibson, Elizabeth. "Benton County – Thumbnail History". HistoryLink.org. March 29, 2004. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ "About The Kennewick courier. (Kennewick, Wash.) 1905-1914". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Gibson, Elizabeth. "Voters fail to move Benton County seat from Prosser following rivalry with Benton City and Kennewick on November 5, 1912." HistoryLink.org. May 29, 2006. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ Trumbo, John (September 22, 2010). "Benton County seat move debated with editors". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "History". Port of Kennewick. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Dorpat, Paul; Sherrard, Jean (2007). Washington Then & Now. Big Earth Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 1-56579-547-4.

- ^ Jim Kershner (May 1, 2008). "Pasco — Thumbnail History". History Link. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Hanford History". United States Department of Energy. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Cary, Annette (October 6, 2013). "Early Hanford workers remember dust, security". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Roland (July 30, 1954). "New Columbia River Bridge Linking Tri-Cities Opened". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. p. 1.

- ^ Jackson, Donald C.; McCullough, David G. (1988). Great American Bridges and Dams. John Wiley & Sons. p. 68-70. ISBN 0-471-14385-5.

- ^ Rigert, Joe (July 9, 1963). "Charge Kennewick as 'sundown town'". Port Angeles Evening News. Port Angeles, Washington. Associated Press. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

A state civil rights board indicated Tuesday Kennewick has virtually barred its gates to Negroes and gained a reputation as a 'sundown town' where Negroes must leave after dark.

- ^ Pihl, Kristi (February 14, 2011). "Black Tri-Citians reflect on struggles, progress". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "The Northwest Remembers Vivid Images After Mount St. Helens Erupted". KNDU-TV. May 18, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "6 inches of Mt. St. Helens ash fell on Lind, WA; half as much on closer cities". KNDU-TV. May 15, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Volcano's ash burp dusts Tri-Cities". Tri-City Herald. February 15, 1991. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ Geranlos, Nicholas (May 23, 1988). "Tri-Cities may become Bi-Cities; Pasco would get boot". Spokane Spokesman-Review.

- ^ Swenson, John (July 25, 1990). "Tri-Cities welcomes Goodwill Games while Soviets fume". United Press International. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Wilma, David (February 25, 2004). "Ted Turner's Goodwill Games open in Seattle on July 20, 1990". History Link. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Morelle, Rebecca (June 18, 2015). "DNA reignites Kennewick Man debate". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "COMPREHENSIVE HOUSING MARKET ANALYSIS - Kennewick-Richland, WA" (PDF). United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. October 1, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Experts say region poised for continued growth". Tri-Cities Business News. 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Together we are one Kennewick". City of Kennewick. 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ a b J. Eric Schuster; Charles W. Gulick; Stephen P. Reidel; Karl R. Fecht; Stephanie Zurenko (1997). Geologic Map of Washington - Southeast Quadrant (PDF) (Map). Washington State Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Kennewick, WA (Map). 1:24,000. United States Geological Survey. 2017.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2012-12-19.

- ^ Carson & Pogue 1996, p.2; Reidel 2005

- ^ "Washington Geologic Information Portal". Washington State Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Clague, John J.; Barendregt, Rene; Enkin, Randolph J.; Foit, Franklin F., Jr. (March 2003). "Paleomagnetic and tephra evidence for tens of Missoula floods in southern Washington". Geology. 31 (3). The Geological Society of America: 247–250. Bibcode:2003Geo....31..247C. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0247:PATEFT>2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bjornstad, Bruce (2006). On the Trail of the Ice Age Floods: A Geological Guide to the Mid-Columbia Basin. Keokee Books; San Point, Idaho. ISBN 978-1-879628-27-4.

- ^ National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS) (1972), Significant Earthquake Database (Data Set), National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K

- ^ Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquakes (PDF) (Report). Cascade Region Earthquake Workgroup. 2013. p. 17. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "WA/OR - United States earthquakes, 1936". Seattle, Washington: Pacific Northwest Seismic Network. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ "Kennewick, Washington Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ COREY CHRISTIANSEN. "WET VS. DRY - SHEDDING SOME LIGHT ON THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST RAIN SHADOW". The Weather Prediction. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Mass, Cliff (2008). The Weather of the Pacific Northwest. University of Washington. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-0-295-98847-4.

- ^ "US Inflation Calculator". Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Elizabeth Gibson (March 31, 2008). "Flood inundates Kennewick and Richland on May 31, 1948". HistoryLink. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Mass (2008), p. 30-32

- ^ McShane, Dan (2012-11-28). "Zintel Canyon Dam". Reading the Washington Landscape. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- ^ Mass (2008), p. 223-229

- ^ Mark Ingalls (April 25, 2018). "Does the Tri-Cities really get 300 days of sunshine a year?". WeatherTogether. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Mass (2008), p. 74

- ^ "Wind gusts hit 70 mph in Tri-Cities". KEPR-TV. December 17, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Mass (2008), p. 180-184

- ^ Burt, Christopher (2004). Extreme Weather. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 251. ISBN 0-393-32658-6.

- ^ "Climate and Weather of Tri-Cities, Washington". Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ Probert, Cameron (August 12, 2018). "Devastating Tri-City wildfire destroys 5 homes, damages 3 more". Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "Tornado Environment Browser". Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- ^ "Storm causes floods and produced a small tornado in Tri-Cities". KNDU-TV. May 23, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ "xmACIS2". NOAA Regional Climate Centers. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Weather History for Pasco, WA [Washington] for July". Archived from the original on 2012-11-11.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 331.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ a b "Major Employers". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "Kennewick, WA". Forbes. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Shopping". Tri-Cities Visitor and Convention Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Southridge". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ JACK J. RASMUSSEN (1971). SOIL SURVEY OF BENTON COUNTY AREA, WASHINGTON (PDF) (Report). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "An Introduction to Kennewick". Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Kennewick-Richland, Washington Unemployment". Department of Numbers. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Morrow County/Umatilla County Transit Development Strategy (PDF) (Report). Oregon Department of Transportation. 2018. pp. 19, 51. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Jade McDowell (March 18, 2016). "Housing market still tight in Hermiston". East Oregonian. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ Kevin McCullen (June 27, 2010). "Booming Boardman has jobs but lacks housing". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Recreation Community Events". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Home". Water Follies. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Art in the Park 2020, a craft show in Richland, Washington". Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Water Follies attendance numbers are in". KNDU-TV. August 1, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Food Finder Map" (PDF). Benton Franklin Fair and Rodeo. 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Horse Heaven Round-Up Rodeo". Benton Franklin Fair and Rodeo. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Sports Tri-Cities". Tri-Cities Visitor and Convention Bureau. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Waterfront Kennewick Hotel". Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ^ Joshi, Pratik (January 7, 2010). "Kennewick's Clover Island lighthouse gets its lid". Wenatchee World. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Ice Harbor Brewery". Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Vista Field". Port of Kennewick. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "2020 Guide to Tri-Cities Wineries". Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Washington Wine Tours". Tri-Cities Visitor and Convention Bureau. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Columbia River Cruises & Snake River Cruises". Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "WHL Network". =Western Hockey League. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Home". American West Football Conference. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Tickets". Minor League Baseball. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Fowler, Annie (September 21, 2012). "Tri-City Americans celebrate 25 years". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Indoor football league considers new Tri-City team". Tri-City Herald. December 15, 2018.

- ^ "IFL Issues Statement on Tri-Cities Fever". www.oursportscentral.com. OurSports Central. June 30, 2016. Retrieved July 1, 2016.

- ^ "AWFC Stats". American West Football Conference. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Defense, Coleman lead Fever to Indoor Bowl V win". www.oursportscentral.com. OurSports Central. July 31, 2005. Retrieved September 30, 2015.

- ^ "Jacobs Sanders Field". Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Atomic City Rollergirls". Flat Track Stats. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "WSU Men's Basketball vs Montana State". Toyota Center. December 9, 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Parks & Facilities". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Athletic Complexes". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Trails & Bike Paths". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Columbia Park Golf Tri-Plex". Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ "Tri-City Water Follies" (PDF). 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ City of Kennewick page. Columbia Park Archived 2008-12-10 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved January 06, 2009.

- ^ "Public Facilities". City of Richland. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ "Play Southridge, WA". City of Kennewick. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ "Play Southridge - Facilities". City of Kennewick. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Trumbo, John (September 8, 2011). "Kennewick to unveil memorial of 9/11 attacks on Sunday". Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ "Story of the Carousel". Gesa Carousel of Dreams. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ^ / Washington State Legislature Optional Municipal Code Retrieved 2020-01-11

- ^ / Municipal Research and Services Center: City and Town Classification Retrieved 2020-01-11

- ^ "Council Election by Wards or Districts". MRSC of Washington. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ [https:// https://www.go2kennewick.com/ArchiveCenter/ViewFile/Item/786 / City of Kennewick 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, Footnote 1 p. 49] Retrieved 2020-01-11

- ^ [https:// https://www.go2kennewick.com/ArchiveCenter/ViewFile/Item/786 / City of Kennewick 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, p. 6] Retrieved 2020-01-11

- ^ / Washington State Legislature Retrieved 2020-01-11

- ^ "Kennewick, WA Education data". Town Charts. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Miseducation - Kennewick School District". ProPublica. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Home Page". Kennewick School District. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ FAQ - Kennewick High School Football

- ^ "Eastern Washington high school stadium guide".

- ^ "Top Kennewick, WA Private Schools". Private School Review. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "About Us". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ "Subscribe to the Tri-Cities Journal of Business". Tri-Cities Journal of Business. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ "Senior Times". Tri-Cities Journal of Business. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ "Tú Decides Media". Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ "Tumbleweird". Mediox. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ "nbcrightnow.com". KNDU. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "About - YakTriNews". Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "FOX 11 and 41 Tri-Cities - Yakima". Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Pasco Contact". Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Radio Stations in Kennewick, Washington". Radio Locator. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "About Us". Northwest Public Radio. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "KRBM-FM Radio Station Coverage Map". Radio Locator. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "RITA - BTS - Transtats". transtats.bts.gov. Retrieved 17 Jan 2020.

- ^ "Pasco (PSC)". Amtrak. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Pasco WA Bus Station". Greyhound Lines. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ Culverwell, Wendy (April 19, 2018). "Are you ready for a woonerf at Kennewick's Vista Field?". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ "2014-2015 Washington State Highway Map with Shaded Relief" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. 2014. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "BFT System Map" (PDF). Ben Franklin Transit. August 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Dial-A-Ride - Services". Ben Franklin Transit. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Utility Information". City of Kennewick. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Energy Fuel Mix". Benton Public Utility District. 2018. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Kennewick General Hospital changes name to Trios Health". KEPR-TV. October 8, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Find Your Local Trauma Center". American Trauma Society. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Emergency Services". Trios Hospital. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Accreditations". Kadlec Regional Medical Center. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Trauma Care". UW Medicine. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Seattle Children's Tri-Cities Clinic". Seattle Children's. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ "Adelle August - The Private Life and times of Adelle August". Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ "Tri-City Americans @ WHL - 1988-1989 Stats". Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ Pernell Watson (June 21, 2001). "Oakland A's Draft High School Junior". www.daileypress.com. Daily Press Media Group. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ "Adam Carriker". Huskers.com. Archived 2009-05-12 at WebCite Retrieved 2016-02-14.

- ^ Turnquist, Kristi (January 21, 2012). "After 25 years in radio, Rick Emerson is all talked out". The Oregonian. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ O'Neal, Dori. "Kennewick grad, Broadway star returns to Tri-Cities". Tri-City Herald. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ "Olaf 'Godzilla' Kolzig". Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ "Michigan: Damon Lusk preview". Motorsport. June 12, 2007. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ "1997 Inductees". Washington Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ "Gay marriage: Openly gay judge, Michael McShane, in spotlight overseeing Oregon case". The Oregonian. April 17, 2014.

- ^ Columnist, Gordon Monson Tribune. "Monson: Utah's Mitchell has transcended turmoil". Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- ^ Pollard, Scot. "All about Scot". PlanetPollard.com. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ^ Booth, Tim (24 August 2008). "Central gave Reilly opportunity to blossom". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Former M's pitcher Swan dies". SWX. May 2, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ Brennan, Dustin (August 6, 2016). "Seattle Mariners shortstop Shawn O'Malley still scrappy after all these years". Retrieved December 29, 2019.