Uganda Volunteer Reserve

| Uganda Volunteer Reserve | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1903–1932, 1940–? |

| Country | Uganda Protectorate |

| Allegiance | British Empire |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Up to 300 men |

| Garrison/HQ | Entebbe, Kampala, Jinja |

| Equipment | Short Magazine Lee–Enfield and Martini–Enfield rifles |

| Engagements |

|

The Uganda Volunteer Reserve (also referred to as the UVR or Uganda VR)[1] was a military unit of the Uganda Protectorate. The UVR was established in March 1903 with support from the British government's Colonial Defence Committee (CDC). The CDC promoted the establishment of such forces in the self-governing parts of the British Empire from which regular British Army troops had been withdrawn. The UVR was organised around "rifle corps" of a minimum of 15 men. Initially only one corps was established, at Entebbe, but a second, at Kampala, was established in June 1914. The members of the UVR were required to attend rifle practice annually and were unpaid, except for a bonus for meeting a minimum marksmanship standard.

During the First World War the UVR, numbering 129 men, was mobilised by the colonial government to assist with the defence of the protectorate. It was reorganised as an infantry battalion with the corps forming companies. A third company was raised consisting entirely of men of Indian ethnicity. The UVR was issued uniforms, locally made in khaki, for the first time and saw expansion in their numbers, reaching 280 by the end of 1914. The UVR was deployed to protect Kampala from looting by British-raised levy troops and some members were posted to the southern frontier, but the unit saw little action and most men were stood down in March 1915. The UVR served as a reserve of experienced leaders for other units such as the East Africa Transport Corps. Some 429 men served with the UVR at some point in the war. One sergeant received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for actions during the defence of a fort in Uganda and three UVR members received a War Office commendation. Three members of the unit were killed in service during the war.

After the war the UVR declined in numbers, owing to the condition of its rifle range at Kampala. It numbered just 49 men in 1930 and the Ugandan colonial government proposed its closure. It was disbanded in 1932, being replaced by subsidised rifle clubs belonging to the Uganda Rifle Association. The UVR was reformed in 1940 as a result of the Second World War but no further details are known.

Formation

[edit]

The Uganda Volunteer Reserve (UVR) has its origins in the Colonial Defence Committee (CDC), which was a British government body that promoted the establishment of self-defence forces in British colonies and protectorates.[2][3] British Army troops had generally been withdrawn from self-governing territories in the early 1870s.[3] The CDC had supported the government of the Uganda Protectorate, in East Africa, to pass the Uganda Volunteer Reserve Ordinance (Ugandan Ordinance No. 5) in March 1903.[2][4] The Ordinance allowed for the formation of a number of "rifle corps" which would together form the Uganda Volunteer Reserve. The Ordinance required each corps to number no fewer than 15 men, all aged 16 or older.[2] Membership was open to British and foreign subjects, with all members taking an oath of allegiance.[2]

The colonial government set aside £775 to pay for weapons, ammunition and equipment for the UVR, on the assumption that 100 recruits would be found. Rifles were issued to UVR members upon receipt of a deposit covering the value of the weapon. All members were required to keep 100 rounds of ammunition on hand in case of mobilisation and were entitled to purchase 300 rounds per annum at cost price for practice purposes. In 1904 the 1903 Ordinance was amended by issue of Ugandan Ordinance No. 17.[4] After protests from members, this ordered that 100 rounds be issued free of charge annually to all members and removed the requirement for the weapon deposit. Members also secured a 43 per cent reduction in the cost charged for ammunition in 1905. Members were responsible for the cost of repairs to their firearm and were liable to a fine of 300 East African rupees if the rifle was lost, sold or rendered unusable.[2] The Ordinance also stipulated a fine of 7–8 rupees for drunkenness during a UVR meeting and of 15 rupees for pointing a rifle at any person, without orders.[5] Each Rifle Corps was permitted to pass its own bye-laws to manage its operations.[5] Each corps had a president who was, ex-officio, the commissioner of the district in which the corps was headquartered and a secretary, who was elected by the members. The secretary was responsible for the property of the corps, all correspondence with the government and the maintenance of order and discipline.[6]

The UVR could be mobilised upon the order of the colonial governor, though the secretary of each corps could authorise a member to absent themselves upon such an occasion. Members were granted two days to respond to the call up and faced 75 rupee fines if they did not attend. Volunteers were unpaid but awarded a 15 rupee annual grant if they qualified as "efficient". Originally all that was required to qualify was to keep the rifle in good order and to fire 21 shots at an annual meeting; in 1904 this was amended to requiring a certain score to be achieved from 200 yards (180 m), 300 yards (270 m) and 400 yards (370 m). The score required (initially 45/105) was increased in 1905 (to 50/105).[5]

Development of units

[edit]

The first corps to be formed was the Entebbe Corps on 28 April 1903. It was the only corps in the unit for several years and was formally named the "Uganda Rifle Corps".[5] By the end of 1903 it had 33 members and by May 1905 it had 43.[5][7] There were discussions in 1906 about forming a second corps at Kampala, as some members of the Entebbe Corps lived there. Nothing progressed until December 1909 when fifteen Kampala residents sent a formal petition to the governor; the Kampala Rifle Corps of the UVR was formed on 4 January 1910. As many of its members were members of the Entebbe Corps the Kampala Corps requested that their subscriptions be refunded and that the older corps provide £20 towards the expenses of the new unit. The Entebbe Corps objected to the formation of the new unit on the basis that the Ordinance prohibited existing members from joining new units and that such persons should be excluded from the 15-man count. The government of Uganda agreed and formally cancelled the Kampala Corps by order on 18 March 1910.[7]

By May 1913 some 34 Kampala residents were members of the Entebbe Corps. On 23 June fourteen of these members, together with one non-member, sent another petition to the governor requesting that a Kampala Corps be formed. This was rejected on the same basis as the 1909 petition. A second petition was sent, signed by 29 persons not already members of the Entebbe Corps and the Kampala Unit was formally established on 25 June.[7] Expansion of the Kampala membership was initially slow, due to the lack of a dedicated shooting range. The unit used the local police range, until that was damaged by heavy rain; a new range was built in May 1914 at the cost of £95.[8] By June 1914 the Uganda Volunteer Reserve of the two corps, with headquarters staff at Entebbe, numbered 129 members (of whom 90 were rated as efficient).[8][4] The unit was equipped with the Short Magazine Lee–Enfield rifle.[4]

The Uganda Volunteer Reserve was active in marksmanship competitions, holding three cups for its members (the Coles Cup established in 1905; the Governor's Cup, in 1909; and Allen Cup in 1913) and competing against teams from other East African territories.[8][7] The unit occasionally sent teams to compete in the National Rifle Association's annual competition at Bisley, England. On 4 December 1913 a sepoy of the 4th King's African Rifles (KAR) Indian contingent was killed by a stray bullet while acting as a score marker on the Entebbe unit's range. An inquiry found that the range's protective mound was in need of reinforcement, that was carried out at the cost of £8, but no case for negligence was found.[7]

By 1913 a formal system was in place to call out the Uganda Volunteer Reserve. Buglers of the military or police would be dispatched to rifle corps headquarters; upon hearing the call members of the unit were to form up at the flag staff outside their local collectorate.[8]

First World War

[edit]

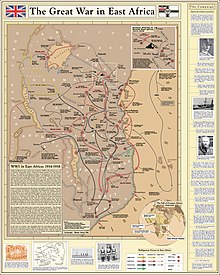

Mobilisation

[edit]The United Kingdom declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, following the invasion of Belgium. The Uganda KAR battalion was mobilised for service outside the territory, leaving the defence of Uganda in the hands of the UVR, the local police and the KAR Reserve of retired ex-soldiers.[9][10] German forces were in close proximity to the protectorate; troops were present on the border with German East Africa to the south and naval forces on Lake Victoria to the south-east. No plans had been prepared for the deployment of the UVR in case of war but on 6 August a meeting of European residents in the protectorate led to almost every able-bodied man of European origin enrolling in the force, greatly expanding its numbers (the UVR still stood at 129 members at the start of the war).[10][8][11] The government amended the Ordinance on 11 August to allow greater flexibility in its deployment of the UVR; the requirement for two days' notice prior to call-up for service was removed and secretaries were no longer permitted to except members from duty or appoint officers, these roles falling to the governor. The new Ordinance brought the UVR under military law (in times of war only) for the first time.[8] The acting governor of Uganda called out the UVR on 13 August and elements of martial law were implemented from 18 August.[8][12]

The first government-appointed officers were installed on 20 August. These included the acting commissioner of the Uganda Protectorate Police as commandant and the assistant district commissioner of Entebbe as adjutant. From 22 August authorisation was granted to pay members of the UVR who were called up, including those receiving training, though no uniform was implemented. On 24 August the UVR was reformed as an infantry battalion of three companies.[13] No. 1 Company consisted of the Entebbe Corps, No. 2 Company the Kampala Corps and No. 3 Company (also based at Kampala) was to accommodate members of Indian ethnicity who were joining the reserve in increasing numbers.[11][13] The KAR Reserve, of two companies, were also stationed at Entebbe.[9]

On 26 August UVR members were split into four classes. Those men in class 1 were available for general service, those in class 2a for service only within the protectorate, those in class 2b only able to serve within their district and those in class 3 the men that had been exempted from service by order of the governor. Members were able to select their own class, though serving civil servants were not permitted to place themselves in class 1 without permission of the Chief Secretary, who headed the protectorate's civil service.[13] As the war progressed, the government reduced its civil service staff, which allowed more men to commit to unrestricted service with the UVR.[14] The European UVR members were of British, French, Dutch, Boer, Danish, Scandinavian, Greek and Armenian origin. Those with citizenship of neutral countries were placed into class 2b only.[15] No. 3 Company consisted largely of former Punjabi soldiers of the British Indian Army, mainly Sikhs with a number of Hindus and Muslims.[15]

By the end of August No.1 Company amounted to 58 personnel, with the remaining two companies numbering 100 combined.[15] Each company was required to prepare a plan to defend their districts and members, though most continued in the peace time occupations. They were required to attend three parades a week and training in Morse and Semaphore messaging was provided. The UVR was issued uniforms for the first time, consisting of khaki tunics, trousers and puttees manufactured by the inmates at the Central Gaol and belts, pouches, bandoliers and haversacks. Brass UVR hat badges, shoulder titles and buttons were also issued, made by the Ugandan Public Works Department and bearing the badge of the protectorate. Because of the expansion of the UVR some members were issued the older Martini–Enfield rifles, and some side arms were also issued.[15]

Early war

[edit]

In the early stage of the war the UVR helped to detain German subjects residing in the protectorate and transfer them to Nairobi for internment.[15] The Kampala companies were also mobilised as a result of the levying of Bugandan tribesmen as spear-armed troops.[16] Some 3,000 of these levies were mobilised during the war, together with 15,000 held in reserve. They patrolled alongside the police on the southern frontier.[9] The levying of Bugandans had previously resulted in looting of the town so the UVR companies were posted to the Indian bazaar and native market to prevent trouble. This was successful, though shambas (subsistence farms) along the route of march were looted.[16]

The German authorities in Rwanda may have initially had intentions to invade Southern Uganda but withdrew in late August, possibly as a result of British patrols on the border.[16][17] The German focus shifted eastwards to Kenya and a threat to Uganda by an advance along the Uganda Railway. German efforts in Southern Uganda shifted to large-scale raids on British posts and the mail communication route to the Belgian Congo.[17][18] Revolts were also incited by the Germans among the African residents of Southern Uganda. British forces on this front were supported by Belgian troops from September 1914.[17]

In October a public meeting at Jinja, in the east of the protectorate, saw interest in forming a new company. Some 26 men agreed to enrol and No. 4 Company of the UVR battalion was formed on 14 October.[6][13] A similar meeting in Tooro, saw 3 European and 20 Indian volunteers agree to enrol, though no corps was formed as the colonial government considered the region safe from German attack.[13]

From October the Ugandan colonial government ordered that all new members be British subjects and required recruits to be approved by the unit's headquarters.[16] In late 1914 the unit was augmented with the appointment of 12 technical staff of Indian origin, including an armourer, blacksmith, compositor and a motor engineer.[13] By Christmas the unit stood at 280 members, of whom 200 were of European origin and the remainder of Indian origin. As training was progressed the compulsory parades were reduced to twice-weekly and then weekly.[16] Most members remained part time, by December only 15 officers, 24 European other ranks and 12 Indian other ranks were paid full time.[19] A "striking force" was established within the UVR at Kampala, with members reporting daily to headquarters to carry messages.[16]

The British military authorities established the Uganda Frontier Force in Southern Uganda to defend the border and requested assistance from the UVR. Some non-commissioned officers from the UVR and six marksmen from the striking force were posted to the Frontier Force at Sango Bay.[16] The UVR also served as a source of officers for other units, mostly to the East Africa Transport Corps but also to the KAR, Uganda Native Medical Corps, Uganda Police Service Battalion, Buganda Rifles, East African Mounted Rifles, on board Ugandan armed vessels and in other transport and supply corps.[20][21] There was also a proposal to deploy 50 of the Indian members as a separate unit and a special training course was started in Kampala, before the idea was dropped.[19]

Demobilisation

[edit]By March 1915 the military situation had improved sufficiently that the majority of the UVR were stood down and placed on indefinite leave; all compulsory training was halted. In August, following the British invasion of Northern Tanganyika, the officer commanding British forces in Uganda advised that the 1914 call-up could be cancelled. At this stage the UVR had reduced in strength to 181 members of all ranks; some 319 European and 110 Indian members served with it at some point during the war.[19] At the end of 1916 the commandant proposed restructuring the UVR to better serve the requirements of the protectorate; but it was decided to leave the unit on it previous footing.[22]

One member of the UVR, Sergeant Charles Thomas Campbell Doran, served in the 18 February defence of Kachumbi Fort in Buddu and received the Distinguished Conduct Medal.[23][22] On 5 September 1916 the governor of Uganda, Sir Frederick Jackson, sent a letter of thanks to the commandant of the UVR for the unit's service during the war. In December 1916 Jackson recommended to the secretary of state for the colonies that several officers be commended for their service. Three officers, Captain (local Major) F.A. Flint, Captain (local Major) E. H. T. Lawrence and Captain (local Lieutenant Colonel) C. Riddick, were subsequently named in a commendation notice issued by the War Office on 7 August 1917. All members of the UVR that were called up were entitled to the British War Medal. A former orderly sergeant in the UVR published a book, The Uganda Volunteers and the War, in 1917 that detailed some of the war-time activities of the unit.[22] Three members of the unit were killed in service during the war: a quartermaster sergeant buried at Simba in July 1915, a captain at Entebbe in June 1916 and a mechanic on transport duties at Bloemfontein in South Africa in November 1917.[24]

Post-war and disbandment

[edit]In 1919 a restructuring of the unit was proposed though, again, it did not proceed. In the post-war years the UVR continued to participate in marksmanship competitions with other East African reserve units. Because of the quantity of war surplus materiel available the Ordinance was modified in 1921 to allow members to purchase unlimited quantities of ammunition from the government at cost price. In the post war years the UVR shot around 16–20,000 rounds per year. Membership of the corps fell to around 70–100 men, of whom around half were of Indian origin.[25] Under the 1921 Ordinance the governor retained the right to mobilise the UVR and, in conjunction with the President of the unit, to appoint its officers.[4] By 1926 the UVR was holding rifle practice only monthly, though volunteers were entitled to claim an increased 200 rounds per year free of charge.[26] In the same year a lack of enlistments caused concerns, with discussions held on replacing the unit with a new European Defence Force or Volunteer Reserve.[26]

The UVR numbered only 49 in 1930, 28 men at Entebbe and 21 at Kampala, a decline blamed on the quality of the rifle range at Kampala. In the same year permission was granted to establish a corps at Jinja, though the Ugandan colonial government questioned the value of the unit. It was proposed that either the UVR be replaced by a formal military reserve unit or be disbanded and replaced by government-subsidised rifle clubs. The government chose the latter option, passing the Uganda Volunteer Reserve (Repeal) Ordinance on 21 November 1932. It was not until 1937 that the Uganda Rifle Association was established as a successor.[25] The UVR was reformed in May 1940, during the Second World War, and received arms and ammunition from the Uganda Rifle Association, but its later history is not known.[27]

See also

[edit]- Kenya Regiment, a white settler formation active from 1937.

References

[edit]- ^ "Abbreviations Used in Military Documents and for Medal Inscriptions". Calgary Military Historical Society. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 65.

- ^ a b Gordon, Donald C. (1962). "The Colonial Defence Committee and Imperial Collaboration: 1885–1904" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly. 77 (4): 526–545. doi:10.2307/2146245. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2146245.

- ^ a b c d e League of Nations Armaments Year Book (PDF). Geneva. 1926. p. 204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 66.

- ^ a b Wallis, H. R. (1920). The Handbook Of Uganda. London: Crown Agents for the Colonies. p. 272.

- ^ a b c d e Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 67.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 68.

- ^ a b c Wallis, H. R. (1920). The Handbook Of Uganda. London: Crown Agents for the Colonies. p. 251.

- ^ a b Lucas, Sir Charles Prestwood (1921). The Empire at War: India, the Mediterranean, eastern colonies &c. Humphrey Milford. p. 234.

- ^ a b Wallis, Henry Richard (1920). The Handbook of Uganda. government of the Uganda Protectorate. p. 251.

- ^ Ehrlich, Cyril (1985). The Uganda Company Limited: The First Fifty Years. The Company. p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 69.

- ^ Stacke, Henry Fitz Maurice (1990). Military Operations, East Africa: August 1914 – September 1916. Battery Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-901627-63-6.

- ^ a b c d e Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 70.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 71.

- ^ a b c Thomas, H. B. (1966). "Kigezi Operations 1914–1917". The Uganda Journal. 30 (2): 165.

- ^ Thomas, H. B. (1966). "Kigezi Operations 1914–1917". The Uganda Journal. 30 (2): 166–167.

- ^ a b c Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 72.

- ^ Abbott, Peter (2006). Colonial Armies in Africa, 1850–1918: Organization, Warfare, Dress and Weapons. Foundry Books. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-901543-07-0.

- ^ Perkins, Roger (1994). Regiments: Regiments and Corps of the British Empire and Commonwealth, 1758–1993 : a Critical Bibliography of Their Published Histories. R. Perkins. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-9506429-3-2.

- ^ a b c Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 73.

- ^ Thomas, H. B. (1966). "Kigezi Operations 1914–1917". The Uganda Journal. 30 (2): 172.

- ^ "Search Results: Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ a b Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 74.

- ^ a b League of Nations Armaments Year Book (PDF). Geneva. 1926. p. 205.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hone, H. R. (January 1941). "The History of the Uganda Volunteer Reserve". Uganda Journal. VIII (2): 75.