Turnsole

Turnsole, katasol, or folium was a dyestuff prepared from the annual plant Chrozophora tinctoria.

History

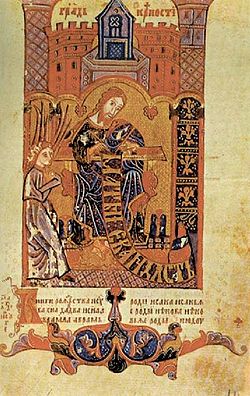

[edit]Turnsole became a mainstay of medieval manuscript illuminators starting with the development of the technique for extracting it in the thirteenth century,[1] when it joined the vegetable-based woad and indigo in the illuminator's repertory. Its use was mostly as substitute of the more expensive Tyrian purple, the famous dye obtained from Murex molluscs.[2] However, the queen of blue colorants was always the expensive lapis lazuli or its substitute azurite, ground to the finest powders. Turnsole was downgraded to a shading glaze and fell out of use in the illuminator's palette by the turn of the seventeenth century, with the easier availability of less fugitive mineral-derived blue pigments. According to its method of preparation, turnsole produced a range of translucent colors from blue, through purple to red, depending on its reaction to the acidity or alkalinity of its environment, in a chemical reaction, not understood in the Middle Ages, that is most familiar in the litmus test.

Folium ("leaf"), was actually derived from the three-lobed fruit (illustration), not the leaves, and medieval recipes are explicit that the fruits must not be broken, or the seeds released, during production of the pigment.[3] The fruits were collected in autumn (August, September).

In the early fifteenth century, Cennino Cennini, in his Libro dell' Arte gives a recipe "XVIII: How you should tint paper turnsole color" and "LXXVI To paint a purple or turnsole drapery in fresco." (though neither of these recipes use or describe turnsole). Textiles soaked in the dye vat would be left in a close damp cellar in an atmosphere produced by pans of urine. It was not realized that the decomposition of urea in the urine was producing ammonia, but the technique reminds us how foul-smelling was the dyer's art.

It was sold impregnated into small pieces of linen and then extracted for use. The colour has been attributed to several different chemicals, including an anthocyanin.[4] Production of the pigment is described in a 15th century manuscript and this was used as the basis of producing the dye.[5] Although the plant extracts do contain several anthocyanins, the colour is due to chrozophoridine, a hermidin derivative.[3]

Turnsole was used as a food colorant, mentioned in Du Fait de Cuisine which suggests steeping it in milk. The French Cook by François Pierre La Varenne (London 1653) mentions turnsole grated in water with a little powder of Iris. It was also used to dye red the rind of a cheese from the Netherlands.[3]

Herbals indicated that the plant grows on sunny, well-drained Mediterranean slopes and called it solsequium ("sun-follower") from its habit of turning its flowers to face the sun; alternatively it might be called "Greater Verucaria";[6] early botanical works gave it synonyms of Morella, Heliotropium tricoccum and Croton tinctorium.

Medicinal uses

[edit]Medicinal properties were ascribed to it in the first century AD by Dioscorides in De Materia Medica and also in medieval pharmacopoeia texts.[3] There have now been studies in the 21st century demonstrating that it did not have significant anti-inflammatory properties.[7]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Thompson, Daniel V. Jr; Hamilton, G.H. (1933). De Arte Illuminandi: The Technique of Manuscript Illumination. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 41.

- ^ M. Aceto, E. Calà, A. Agostino, G. Fenoglio, A. Idone, C. Porte, M. Gulmini, On the identification of folium and orchil on illuminated manuscripts, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2016.08.046.

- ^ a b c d Nabais, P; Oliviera, J; Pina, F; Teixeira, N; de Freitas, V; Brás, NF; Clemente, A; Rangel, M; Silva, AMS; Melo, MJ (2020). "A 1000-year-old mystery solved: Unlocking the molecular structure for the medieval blue from Chrozophora tinctoria, also known as folium". Science Advances. 6 (16): eaaz7772. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz7772. PMC 7164948. PMID 32426456.

- ^ Schultz, Isaac (17 April 2020). "The Mystery of a Medieval Blue Ink Has Been Solved". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Melo, Maria J.; Castro, Rita; Nabais, Paula; Vitorino, Tatiana (2018). "The book on how to make all the colour paints for illuminating books: unravelling a Portuguese Hebrew illuminators' manual". Heritage Science. 6: 44. doi:10.1186/s40494-018-0208-z.

- ^ So named in a recipe for producing the colorant, Pro tornasolio faciendo, British Library, Sloane MS 1754, folio 235 verso, quoted in Daniel V. Thompson, Jr., "Medieval Color-Making: Tractatus Qualiter Quilibet Artificialis Color Fieri Possit from Paris, B. N., MS. latin 6749", Isis 22.2 (February 1935, pp. 456–468) p 458 note.

- ^ Abdallah, HM; Almowallad, FH; Esmat, A; Shehata, IA; Abdel-Sattar, EA (2015). "Anti-inflammatory activity of flavonoids from Chrozophora tinctoria". Phytochemistry Letters. 13: 74–80. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2015.05.008. Retrieved 20 April 2020.