Truth

| Part of a series on |

| Epistemology |

|---|

Truth or verity is the property of being in accord with fact or reality.[1] In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs, propositions, and declarative sentences.[2]

Truth is usually held to be the opposite of false statement. The concept of truth is discussed and debated in various contexts, including philosophy, art, theology, law, and science. Most human activities depend upon the concept, where its nature as a concept is assumed rather than being a subject of discussion, including journalism and everyday life. Some philosophers view the concept of truth as basic, and unable to be explained in any terms that are more easily understood than the concept of truth itself.[2] Most commonly, truth is viewed as the correspondence of language or thought to a mind-independent world. This is called the correspondence theory of truth.

Various theories and views of truth continue to be debated among scholars, philosophers, and theologians.[2][3] There are many different questions about the nature of truth which are still the subject of contemporary debates. These include the question of defining truth; whether it is even possible to give an informative definition of truth; identifying things as truth-bearers capable of being true or false; if truth and falsehood are bivalent, or if there are other truth values; identifying the criteria of truth that allow us to identify it and to distinguish it from falsehood; the role that truth plays in constituting knowledge; and, if truth is always absolute or if it can be relative to one's perspective.

Definition and etymology

[edit]The English word truth is derived from Old English tríewþ, tréowþ, trýwþ, Middle English trewþe, cognate to Old High German triuwida, Old Norse tryggð. Like troth, it is a -th nominalisation of the adjective true (Old English tréowe).

The English word true is from Old English (West Saxon) (ge)tríewe, tréowe, cognate to Old Saxon (gi)trûui, Old High German (ga)triuwu (Modern German treu "faithful"), Old Norse tryggr, Gothic triggws,[4] all from a Proto-Germanic *trewwj- "having good faith", perhaps ultimately from PIE *dru- "tree", on the notion of "steadfast as an oak" (e.g., Sanskrit [[[:wikt:दारु#Sanskrit|dā́ru]]] Error: {{Lang}}: Non-latn text (pos 9)/Latn script subtag mismatch (help) "(piece of) wood").[5] Old Norse trú, "faith, word of honour; religious faith, belief"[6] (archaic English troth "loyalty, honesty, good faith", compare Ásatrú).

Thus, "truth" involves both the quality of "faithfulness, fidelity, loyalty, sincerity, veracity",[7] and that of "agreement with fact or reality", in Anglo-Saxon expressed by sōþ (Modern English sooth).

All Germanic languages besides English have introduced a terminological distinction between truth "fidelity" and truth "factuality". To express "factuality", North Germanic opted for nouns derived from sanna "to assert, affirm", while continental West Germanic (German and Dutch) opted for continuations of wâra "faith, trust, pact" (cognate to Slavic věra "(religious) faith", but influenced by Latin verus). Romance languages use terms following the Latin veritas, while the Greek aletheia, Russian pravda, South Slavic istina and Sanskrit sat (related to English sooth and North Germanic sanna) have separate etymological origins.

In some modern contexts, the word "truth" is used to refer to fidelity to an original or standard. It can also be used in the context of being "true to oneself" in the sense of acting with authenticity.[1]

Major theories

[edit]

The question of what is a proper basis for deciding how words, symbols, ideas and beliefs may properly be considered true, whether by a single person or an entire society, is dealt with by the five most prevalent substantive theories of truth listed below. Each presents perspectives that are widely shared by published scholars.[8][9][10]: 309–330

Theories other than the most prevalent substantive theories are also discussed. According to a survey of professional philosophers and others on their philosophical views which was carried out in November 2009 (taken by 3226 respondents, including 1803 philosophy faculty members and/or PhDs and 829 philosophy graduate students) 45% of respondents accept or lean toward correspondence theories, 21% accept or lean toward deflationary theories and 14% epistemic theories.[11]

Substantive

[edit]Correspondence

[edit]Correspondence theories emphasize that true beliefs and true statements correspond to the actual state of affairs.[12] This type of theory stresses a relationship between thoughts or statements on one hand, and things or objects on the other. It is a traditional model tracing its origins to ancient Greek philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle.[13] This class of theories holds that the truth or the falsity of a representation is determined in principle entirely by how it relates to "things" according to whether it accurately describes those "things". A classic example of correspondence theory is the statement by the thirteenth century philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas: "Veritas est adaequatio rei et intellectus" ("Truth is the adequation of things and intellect"), which Aquinas attributed to the ninth century Neoplatonist Isaac Israeli.[14][15][16] Aquinas also restated the theory as: "A judgment is said to be true when it conforms to the external reality".[17]

Correspondence theory centres heavily around the assumption that truth is a matter of accurately copying what is known as "objective reality" and then representing it in thoughts, words, and other symbols.[18] Many modern theorists have stated that this ideal cannot be achieved without analysing additional factors.[8][19] For example, language plays a role in that all languages have words to represent concepts that are virtually undefined in other languages. The German word Zeitgeist is one such example: one who speaks or understands the language may "know" what it means, but any translation of the word apparently fails to accurately capture its full meaning (this is a problem with many abstract words, especially those derived in agglutinative languages). Thus, some words add an additional parameter to the construction of an accurate truth predicate. Among the philosophers who grappled with this problem is Alfred Tarski, whose semantic theory is summarized further on.[20]

Proponents of several of the theories below have gone further to assert that there are yet other issues necessary to the analysis, such as interpersonal power struggles, community interactions, personal biases, and other factors involved in deciding what is seen as truth.

Coherence

[edit]For coherence theories in general, truth requires a proper fit of elements within a whole system. Very often, coherence is taken to imply something more than simple logical consistency; often there is a demand that the propositions in a coherent system lend mutual inferential support to each other. So, for example, the completeness and comprehensiveness of the underlying set of concepts is a critical factor in judging the validity and usefulness of a coherent system.[21] A pervasive tenet of coherence theories is the idea that truth is primarily a property of whole systems of propositions, and can be ascribed to individual propositions only according to their coherence with the whole. Among the assortment of perspectives commonly regarded as coherence theory, theorists differ on the question of whether coherence entails many possible true systems of thought or only a single absolute system.

Some variants of coherence theory are claimed to describe the essential and intrinsic properties of formal systems in logic and mathematics.[22] Formal reasoners are content to contemplate axiomatically independent and sometimes mutually contradictory systems side by side, for example, the various alternative geometries. On the whole, coherence theories have been rejected for lacking justification in their application to other areas of truth, especially with respect to assertions about the natural world, empirical data in general, assertions about practical matters of psychology and society, especially when used without support from the other major theories of truth.[23]

Coherence theories distinguish the thought of rationalist philosophers, particularly of Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, along with the British philosopher F. H. Bradley.[24] They have found a resurgence also among several proponents of logical positivism, notably Otto Neurath and Carl Hempel.

Pragmatic

[edit]The three most influential forms of the pragmatic theory of truth were introduced around the turn of the 20th century by Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. Although there are wide differences in viewpoint among these and other proponents of pragmatic theory, they hold in common that truth is verified and confirmed by the results of putting one's concepts into practice.[25]

Peirce defines it: "Truth is that concordance of an abstract statement with the ideal limit towards which endless investigation would tend to bring scientific belief, which concordance the abstract statement may possess by virtue of the confession of its inaccuracy and one-sidedness, and this confession is an essential ingredient of truth."[26] This statement stresses Peirce's view that ideas of approximation, incompleteness, and partiality, what he describes elsewhere as fallibilism and "reference to the future", are essential to a proper conception of truth. Although Peirce uses words like concordance and correspondence to describe one aspect of the pragmatic sign relation, he is also quite explicit in saying that definitions of truth based on mere correspondence are no more than nominal definitions, which he accords a lower status than real definitions.

James' version of pragmatic theory, while complex, is often summarized by his statement that "the 'true' is only the expedient in our way of thinking, just as the 'right' is only the expedient in our way of behaving."[27] By this, James meant that truth is a quality, the value of which is confirmed by its effectiveness when applying concepts to practice (thus, "pragmatic").

Dewey, less broadly than James but more broadly than Peirce, held that inquiry, whether scientific, technical, sociological, philosophical, or cultural, is self-corrective over time if openly submitted for testing by a community of inquirers in order to clarify, justify, refine, and/or refute proposed truths.[28]

Though not widely known, a new variation of the pragmatic theory was defined and wielded successfully from the 20th century forward. Defined and named by William Ernest Hocking, this variation is known as "negative pragmatism". Essentially, what works may or may not be true, but what fails cannot be true because the truth always works.[29] Philosopher of science Richard Feynman also subscribed to it: "We never are definitely right, we can only be sure we are wrong."[30] This approach incorporates many of the ideas from Peirce, James, and Dewey. For Peirce, the idea of "endless investigation would tend to bring about scientific belief" fits negative pragmatism in that a negative pragmatist would never stop testing. As Feynman noted, an idea or theory "could never be proved right, because tomorrow's experiment might succeed in proving wrong what you thought was right."[30] Similarly, James and Dewey's ideas also ascribe truth to repeated testing which is "self-corrective" over time.

Pragmatism and negative pragmatism are also closely aligned with the coherence theory of truth in that any testing should not be isolated but rather incorporate knowledge from all human endeavors and experience. The universe is a whole and integrated system, and testing should acknowledge and account for its diversity. As Feynman said, "... if it disagrees with experiment, it is wrong."[30]: 150

Constructivist

[edit]Social constructivism holds that truth is constructed by social processes, is historically and culturally specific, and that it is in part shaped through the power struggles within a community. Constructivism views all of our knowledge as "constructed," because it does not reflect any external "transcendent" realities (as a pure correspondence theory might hold). Rather, perceptions of truth are viewed as contingent on convention, human perception, and social experience. It is believed by constructivists that representations of physical and biological reality, including race, sexuality, and gender, are socially constructed.

Giambattista Vico was among the first to claim that history and culture were man-made. Vico's epistemological orientation unfolds in one axiom: verum ipsum factum—"truth itself is constructed". Hegel and Marx were among the other early proponents of the premise that truth is, or can be, socially constructed. Marx, like many critical theorists who followed, did not reject the existence of objective truth, but rather distinguished between true knowledge and knowledge that has been distorted through power or ideology. For Marx, scientific and true knowledge is "in accordance with the dialectical understanding of history" and ideological knowledge is "an epiphenomenal expression of the relation of material forces in a given economic arrangement".[31][page needed]

Consensus

[edit]Consensus theory holds that truth is whatever is agreed upon, or in some versions, might come to be agreed upon, by some specified group. Such a group might include all human beings, or a subset thereof consisting of more than one person.

Among the current advocates of consensus theory as a useful accounting of the concept of "truth" is the philosopher Jürgen Habermas.[32] Habermas maintains that truth is what would be agreed upon in an ideal speech situation.[33] Among the current strong critics of consensus theory is the philosopher Nicholas Rescher.[34]

Minimalist

[edit]Deflationary

[edit]Modern developments in the field of philosophy have resulted in the rise of a new thesis: that the term truth does not denote a real property of sentences or propositions. This thesis is in part a response to the common use of truth predicates (e.g., that some particular thing "... is true") which was particularly prevalent in philosophical discourse on truth in the first half of the 20th century. From this point of view, to assert that "'2 + 2 = 4' is true" is logically equivalent to asserting that "2 + 2 = 4", and the phrase "is true" is—philosophically, if not practically (see: "Michael" example, below)—completely dispensable in this and every other context. In common parlance, truth predicates are not commonly heard, and it would be interpreted as an unusual occurrence were someone to utilize a truth predicate in an everyday conversation when asserting that something is true. Newer perspectives that take this discrepancy into account, and work with sentence structures as actually employed in common discourse, can be broadly described:

- as deflationary theories of truth, since they attempt to deflate the presumed importance of the words "true" or truth,

- as disquotational theories, to draw attention to the disappearance of the quotation marks in cases like the above example, or

- as minimalist theories of truth.[8][35]

Whichever term is used, deflationary theories can be said to hold in common that "the predicate 'true' is an expressive convenience, not the name of a property requiring deep analysis."[8] Once we have identified the truth predicate's formal features and utility, deflationists argue, we have said all there is to be said about truth. Among the theoretical concerns of these views is to explain away those special cases where it does appear that the concept of truth has peculiar and interesting properties. (See, e.g., Semantic paradoxes, and below.)

The scope of deflationary principles is generally limited to representations that resemble sentences. They do not encompass a broader range of entities that are typically considered true or otherwise. In addition, some deflationists point out that the concept employed in "... is true" formulations does enable us to express things that might otherwise require infinitely long sentences; for example, one cannot express confidence in Michael's accuracy by asserting the endless sentence:

This assertion can instead be succinctly expressed by saying: What Michael says is true.[36]

Redundancy and related

[edit]An early variety of deflationary theory is the redundancy theory of truth, so-called because—in examples like those above, e.g. "snow is white [is true]"—the concept of "truth" is redundant and need not have been articulated; that is, it is merely a word that is traditionally used in conversation or writing, generally for emphasis, but not a word that actually equates to anything in reality. This theory is commonly attributed to Frank P. Ramsey, who held that the use of words like fact and truth was nothing but a roundabout way of asserting a proposition, and that treating these words as separate problems in isolation from judgment was merely a "linguistic muddle".[8][37][38]

A variant of redundancy theory is the "disquotational" theory, which uses a modified form of the logician Alfred Tarski's schema: proponents observe that to say that "'P' is true" is to assert "P". A version of this theory was defended by C. J. F. Williams (in his book What is Truth?). Yet another version of deflationism is the prosentential theory of truth, first developed by Dorothy Grover, Joseph Camp, and Nuel Belnap as an elaboration of Ramsey's claims. They argue that utterances such as "that's true", when said in response to (e.g.) "it's raining", are "prosentences"—expressions that merely repeat the content of other expressions. In the same way that it means the same as my dog in the statement "my dog was hungry, so I fed it", that's true is supposed to mean the same as it's raining when the former is said in reply to the latter.

As noted above, proponents of these ideas do not necessarily follow Ramsey in asserting that truth is not a property; rather, they can be understood to say that, for instance, the assertion "P" may well involve a substantial truth—it is only the redundancy involved in statements such as "that's true" (i.e., a prosentence) which is to be minimized.[8]

Performative

[edit]Attributed to philosopher P. F. Strawson is the performative theory of truth which holds that to say "'Snow is white' is true" is to perform the speech act of signaling one's agreement with the claim that snow is white (much like nodding one's head in agreement). The idea that some statements are more actions than communicative statements is not as odd as it may seem. For example, when a wedding couple says "I do" at the appropriate time in a wedding, they are performing the act of taking the other to be their lawful wedded spouse. They are not describing themselves as taking the other, but actually doing so (perhaps the most thorough analysis of such "illocutionary acts" is J. L. Austin, most notably in How to Do Things With Words[39]).

Strawson holds that a similar analysis is applicable to all speech acts, not just illocutionary ones: "To say a statement is true is not to make a statement about a statement, but rather to perform the act of agreeing with, accepting, or endorsing a statement. When one says 'It's true that it's raining,' one asserts no more than 'It's raining.' The function of [the statement] 'It's true that ...' is to agree with, accept, or endorse the statement that 'it's raining.'" [40]

Philosophical skepticism

[edit]Philosophical skepticism is generally any doubt of one or more items of knowledge or belief which ascribe truth to their assertions and propositions.[41][42] The primary target of philosophical skepticism is epistemology, but it can be applied to any domain, such as the supernatural, morality (moral skepticism), and religion (skepticism about the existence of God).[43]

Philosophical skepticism comes in various forms. Radical forms of skepticism deny that knowledge or rational belief is possible and urge us to suspend judgment regarding ascription of truth on many or all controversial matters. More moderate forms of skepticism claim only that nothing can be known with certainty, or that we can know little or nothing about the "big questions" in life, such as whether God exists or whether there is an afterlife. Religious skepticism is "doubt concerning basic religious principles (such as immortality, providence, and revelation)".[44] Scientific skepticism concerns testing beliefs for reliability, by subjecting them to systematic investigation using the scientific method, to discover empirical evidence for them.

Pluralist

[edit]Several of the major theories of truth hold that there is a particular property the having of which makes a belief or proposition true. Pluralist theories of truth assert that there may be more than one property that makes propositions true: ethical propositions might be true by virtue of coherence. Propositions about the physical world might be true by corresponding to the objects and properties they are about.

Some of the pragmatic theories, such as those by Charles Peirce and William James, included aspects of correspondence, coherence and constructivist theories.[26][27] Crispin Wright argued in his 1992 book Truth and Objectivity that any predicate which satisfied certain platitudes about truth qualified as a truth predicate. In some discourses, Wright argued, the role of the truth predicate might be played by the notion of superassertibility.[45] Michael Lynch, in a 2009 book Truth as One and Many, argued that we should see truth as a functional property capable of being multiply manifested in distinct properties like correspondence or coherence.[46]

Formal theories

[edit]Logic

[edit]Logic is concerned with the patterns in reason that can help tell if a proposition is true or not. Logicians use formal languages to express the truths they are concerned with, and as such there is only truth under some interpretation or truth within some logical system.

A logical truth (also called an analytic truth or a necessary truth) is a statement that is true in all possible worlds[47] or under all possible interpretations, as contrasted to a fact (also called a synthetic claim or a contingency), which is only true in this world as it has historically unfolded. A proposition such as "If p and q, then p" is considered to be a logical truth because of the meaning of the symbols and words in it and not because of any fact of any particular world. They are such that they could not be untrue.

Degrees of truth in logic may be represented using two or more discrete values, as with bivalent logic (or binary logic), three-valued logic, and other forms of finite-valued logic.[48][49] Truth in logic can be represented using numbers comprising a continuous range, typically between 0 and 1, as with fuzzy logic and other forms of infinite-valued logic.[50][51] In general, the concept of representing truth using more than two values is known as many-valued logic.[52]

Mathematics

[edit]

There are two main approaches to truth in mathematics. They are the model theory of truth and the proof theory of truth.[53]

Historically, with the nineteenth century development of Boolean algebra, mathematical models of logic began to treat "truth", also represented as "T" or "1", as an arbitrary constant. "Falsity" is also an arbitrary constant, which can be represented as "F" or "0". In propositional logic, these symbols can be manipulated according to a set of axioms and rules of inference, often given in the form of truth tables.

In addition, from at least the time of Hilbert's program at the turn of the twentieth century to the proof of Gödel's incompleteness theorems and the development of the Church–Turing thesis in the early part of that century, true statements in mathematics were generally assumed to be those statements that are provable in a formal axiomatic system.[54]

The works of Kurt Gödel, Alan Turing, and others shook this assumption, with the development of statements that are true but cannot be proven within the system.[55] Two examples of the latter can be found in Hilbert's problems. Work on Hilbert's 10th problem led in the late twentieth century to the construction of specific Diophantine equations for which it is undecidable whether they have a solution,[56] or even if they do, whether they have a finite or infinite number of solutions. More fundamentally, Hilbert's first problem was on the continuum hypothesis.[57] Gödel and Paul Cohen showed that this hypothesis cannot be proved or disproved using the standard axioms of set theory.[58] In the view of some, then, it is equally reasonable to take either the continuum hypothesis or its negation as a new axiom.

Gödel thought that the ability to perceive the truth of a mathematical or logical proposition is a matter of intuition, an ability he admitted could be ultimately beyond the scope of a formal theory of logic or mathematics[59][60] and perhaps best considered in the realm of human comprehension and communication. But he commented, "The more I think about language, the more it amazes me that people ever understand each other at all".[61]

Tarski's semantics

[edit]The semantic theory of truth has as its general case for a given language:

- 'P' is true if and only if P

where 'P' refers to the sentence (the sentence's name), and P is just the sentence itself.

Tarski's theory of truth (named after Alfred Tarski) was developed for formal languages, such as formal logic. Here he restricted it in this way: no language could contain its own truth predicate, that is, the expression is true could only apply to sentences in some other language. The latter he called an object language, the language being talked about. (It may, in turn, have a truth predicate that can be applied to sentences in still another language.) The reason for his restriction was that languages that contain their own truth predicate will contain paradoxical sentences such as, "This sentence is not true". As a result, Tarski held that the semantic theory could not be applied to any natural language, such as English, because they contain their own truth predicates. Donald Davidson used it as the foundation of his truth-conditional semantics and linked it to radical interpretation in a form of coherentism.

Bertrand Russell is credited with noticing the existence of such paradoxes even in the best symbolic formations of mathematics in his day, in particular the paradox that came to be named after him, Russell's paradox. Russell and Whitehead attempted to solve these problems in Principia Mathematica by putting statements into a hierarchy of types, wherein a statement cannot refer to itself, but only to statements lower in the hierarchy. This in turn led to new orders of difficulty regarding the precise natures of types and the structures of conceptually possible type systems that have yet to be resolved to this day.

Kripke's semantics

[edit]Kripke's theory of truth (named after Saul Kripke) contends that a natural language can in fact contain its own truth predicate without giving rise to contradiction. He showed how to construct one as follows:

- Beginning with a subset of sentences of a natural language that contains no occurrences of the expression "is true" (or "is false"). So, The barn is big is included in the subset, but not "The barn is big is true", nor problematic sentences such as "This sentence is false".

- Defining truth just for the sentences in that subset.

- Extending the definition of truth to include sentences that predicate truth or falsity of one of the original subset of sentences. So "The barn is big is true" is now included, but not either "This sentence is false" nor "'The barn is big is true' is true".

- Defining truth for all sentences that predicate truth or falsity of a member of the second set. Imagine this process repeated infinitely, so that truth is defined for The barn is big; then for "The barn is big is true"; then for "'The barn is big is true' is true", and so on.

Truth never gets defined for sentences like This sentence is false, since it was not in the original subset and does not predicate truth of any sentence in the original or any subsequent set. In Kripke's terms, these are "ungrounded." Since these sentences are never assigned either truth or falsehood even if the process is carried out infinitely, Kripke's theory implies that some sentences are neither true nor false. This contradicts the principle of bivalence: every sentence must be either true or false. Since this principle is a key premise in deriving the liar paradox, the paradox is dissolved.[62]

The proof sketch for Gödel's first incompleteness theorem shows self-reference cannot be avoided naively[clarification needed][citation needed], since propositions about seemingly unrelated objects can have an informal self-referential meaning; in Gödel's work, these objects are integer numbers, and they have an informal meaning regarding propositions[clarification needed]. In fact, this idea — manifested by the diagonal lemma—is the basis for Tarski's theorem that truth cannot be consistently defined.[clarification needed]

It has thus been claimed[63] that Kripke's system indeed leads to contradiction[dubious – discuss]: while its truth predicate is only partial, it does give truth value (true/false) to propositions such as the one built in Tarski's proof,[dubious – discuss] and is therefore inconsistent. While there is still a debate on whether Tarski's proof can be implemented to every similar partial truth system,[clarification needed] none have been shown to be consistent by acceptable methods used in mathematical logic.[citation needed]

Kripke's semantics are related to the use of topoi and other concepts from category theory in the study of mathematical logic.[64] They provide a choice of formal semantics for intuitionistic logic.

Folk beliefs

[edit]The truth predicate "P is true" has great practical value in human language, allowing efficient endorsement or impeaching of claims made by others, to emphasize the truth or falsity of a statement, or to enable various indirect (Gricean) conversational implications.[65] Individuals or societies will sometime punish "false" statements to deter falsehoods;[66] the oldest surviving law text, the Code of Ur-Nammu, lists penalties for false accusations of sorcery or adultery, as well as for committing perjury in court. Even four-year-old children can pass simple "false belief" tests and successfully assess that another individual's belief diverges from reality in a specific way;[67] by adulthood there are strong implicit intuitions about "truth" that form a "folk theory" of truth. These intuitions include:[68]

- Capture (T-in): If P, then P is true

- Release (T-out): If P is true, then P

- Noncontradiction: A statement cannot be both true and false

- Normativity: It is usually good to believe what is true

- False beliefs: The notion that believing a statement does not necessarily make it true

Like many folk theories, the folk theory of truth is useful in everyday life but, upon deep analysis, turns out to be technically self-contradictory; in particular, any formal system that fully obeys "capture and release" semantics for truth (also known as the T-schema), and that also respects classical logic, is provably inconsistent and succumbs to the liar paradox or to a similar contradiction.[69]

Ancient Greek philosophy

[edit]Socrates', Plato's and Aristotle's ideas about truth are seen by some as consistent with correspondence theory. In his Metaphysics, Aristotle stated: "To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true".[70] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy proceeds to say of Aristotle:[70]

... Aristotle sounds much more like a genuine correspondence theorist in the Categories (12b11, 14b14), where he talks of "underlying things" that make statements true and implies that these "things" (pragmata) are logically structured situations or facts (viz., his sitting, his not sitting). Most influential is his claim in De Interpretatione (16a3) that thoughts are "likenesses" (homoiosis) of things. Although he nowhere defines truth in terms of a thought's likeness to a thing or fact, it is clear that such a definition would fit well into his overall philosophy of mind. ...

Similar statements can also be found in Plato's dialogues (Cratylus 385b2, Sophist 263b).[70]

Some Greek philosophers maintained that truth was either not accessible to mortals, or of greatly limited accessibility, forming early philosophical skepticism. Among these were Xenophanes, Democritus, and Pyrrho, the founder of Pyrrhonism, who argued that there was no criterion of truth.

The Epicureans believed that all sense perceptions were true,[71][72] and that errors arise in how we judge those perceptions.

The Stoics conceived truth as accessible from impressions via cognitive grasping.

Medieval philosophy

[edit]Avicenna (980–1037)

[edit]In early Islamic philosophy, Avicenna (Ibn Sina) defined truth in his work Kitab Al-Shifa The Book of Healing, Book I, Chapter 8, as:

What corresponds in the mind to what is outside it.[73]

Avicenna elaborated on his definition of truth later in Book VIII, Chapter 6:

The truth of a thing is the property of the being of each thing which has been established in it.[74]

This definition is but a rendering of the medieval Latin translation of the work by Simone van Riet.[75] A modern translation of the original Arabic text states:

Truth is also said of the veridical belief in the existence [of something].[76]

Aquinas (1225–1274)

[edit]Reevaluating Avicenna, and also Augustine and Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas stated in his Disputed Questions on Truth:

A natural thing, being placed between two intellects, is called true insofar as it conforms to either. It is said to be true with respect to its conformity with the divine intellect insofar as it fulfills the end to which it was ordained by the divine intellect ... With respect to its conformity with a human intellect, a thing is said to be true insofar as it is such as to cause a true estimate about itself.[77]

Thus, for Aquinas, the truth of the human intellect (logical truth) is based on the truth in things (ontological truth).[78] Following this, he wrote an elegant re-statement of Aristotle's view in his Summa I.16.1:

Veritas est adæquatio intellectus et rei.

(Truth is the conformity of the intellect and things.)

Aquinas also said that real things participate in the act of being of the Creator God who is Subsistent Being, Intelligence, and Truth. Thus, these beings possess the light of intelligibility and are knowable. These things (beings; reality) are the foundation of the truth that is found in the human mind, when it acquires knowledge of things, first through the senses, then through the understanding and the judgement done by reason. For Aquinas, human intelligence ("intus", within and "legere", to read) has the capability to reach the essence and existence of things because it has a non-material, spiritual element, although some moral, educational, and other elements might interfere with its capability.

Changing concepts of truth in the Middle Ages

[edit]Richard Firth Green examined the concept of truth in the later Middle Ages in his A Crisis of Truth, and concludes that roughly during the reign of Richard II of England the very meaning of the concept changes. The idea of the oath, which was so much part and parcel of for instance Romance literature,[79] changes from a subjective concept to a more objective one (in Derek Pearsall's summary).[80] Whereas truth (the "trouthe" of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight) was first "an ethical truth in which truth is understood to reside in persons", in Ricardian England it "transforms ... into a political truth in which truth is understood to reside in documents".[81]

Modern philosophy

[edit]Kant (1724–1804)

[edit]Immanuel Kant endorses a definition of truth along the lines of the correspondence theory of truth.[70] Kant writes in the Critique of Pure Reason: "The nominal definition of truth, namely that it is the agreement of cognition with its object, is here granted and presupposed".[82] He denies that this correspondence definition of truth provides us with a test or criterion to establish which judgements are true. He states in his logic lectures:[83]

... Truth, it is said, consists in the agreement of cognition with its object. In consequence of this mere nominal definition, my cognition, to count as true, is supposed to agree with its object. Now I can compare the object with my cognition, however, only by cognizing it. Hence my cognition is supposed to confirm itself, which is far short of being sufficient for truth. For since the object is outside me, the cognition in me, all I can ever pass judgement on is whether my cognition of the object agrees with my cognition of the object.

The ancients called such a circle in explanation a diallelon. And actually the logicians were always reproached with this mistake by the sceptics, who observed that with this definition of truth it is just as when someone makes a statement before a court and in doing so appeals to a witness with whom no one is acquainted, but who wants to establish his credibility by maintaining that the one who called him as witness is an honest man. The accusation was grounded, too. Only the solution of the indicated problem is impossible without qualification and for every man. ...

This passage makes use of his distinction between nominal and real definitions. A nominal definition explains the meaning of a linguistic expression. A real definition describes the essence of certain objects and enables us to determine whether any given item falls within the definition.[84] Kant holds that the definition of truth is merely nominal and, therefore, we cannot employ it to establish which judgements are true. According to Kant, the ancient skeptics were critical of the logicians for holding that, by means of a merely nominal definition of truth, they can establish which judgements are true. They were trying to do something that is "impossible without qualification and for every man".[83]

Hegel (1770–1831)

[edit]G. W. F. Hegel distanced his philosophy from empiricism by presenting truth as a self-moving process, rather than a matter of merely subjective thoughts. Hegel's truth is analogous to an organism in that it is self-determining according to its own inner logic: "Truth is its own self-movement within itself."[85]

Schopenhauer (1788–1860)

[edit]For Arthur Schopenhauer,[86] a judgment is a combination or separation of two or more concepts. If a judgment is to be an expression of knowledge, it must have a sufficient reason or ground by which the judgment could be called true. Truth is the reference of a judgment to something different from itself which is its sufficient reason (ground). Judgments can have material, formal, transcendental, or metalogical truth. A judgment has material truth if its concepts are based on intuitive perceptions that are generated from sensations. If a judgment has its reason (ground) in another judgment, its truth is called logical or formal. If a judgment, of, for example, pure mathematics or pure science, is based on the forms (space, time, causality) of intuitive, empirical knowledge, then the judgment has transcendental truth.

Kierkegaard (1813–1855)

[edit]When Søren Kierkegaard, as his character Johannes Climacus, ends his writings: My thesis was, subjectivity, heartfelt is the truth, he does not advocate for subjectivism in its extreme form (the theory that something is true simply because one believes it to be so), but rather that the objective approach to matters of personal truth cannot shed any light upon that which is most essential to a person's life. Objective truths are concerned with the facts of a person's being, while subjective truths are concerned with a person's way of being. Kierkegaard agrees that objective truths for the study of subjects like mathematics, science, and history are relevant and necessary, but argues that objective truths do not shed any light on a person's inner relationship to existence. At best, these truths can only provide a severely narrowed perspective that has little to do with one's actual experience of life.[87]

While objective truths are final and static, subjective truths are continuing and dynamic. The truth of one's existence is a living, inward, and subjective experience that is always in the process of becoming. The values, morals, and spiritual approaches a person adopts, while not denying the existence of objective truths of those beliefs, can only become truly known when they have been inwardly appropriated through subjective experience. Thus, Kierkegaard criticizes all systematic philosophies which attempt to know life or the truth of existence via theories and objective knowledge about reality. As Kierkegaard claims, human truth is something that is continually occurring, and a human being cannot find truth separate from the subjective experience of one's own existing, defined by the values and fundamental essence that consist of one's way of life.[88]

Nietzsche (1844–1900)

[edit]Friedrich Nietzsche believed the search for truth, or 'the will to truth', was a consequence of the will to power of philosophers. He thought that truth should be used as long as it promoted life and the will to power, and he thought untruth was better than truth if it had this life enhancement as a consequence. As he wrote in Beyond Good and Evil, "The falseness of a judgment is to us not necessarily an objection to a judgment ... The question is to what extent it is life-advancing, life-preserving, species-preserving, perhaps even species-breeding ..." (aphorism 4). He proposed the will to power as a truth only because, according to him, it was the most life-affirming and sincere perspective one could have.

Robert Wicks discusses Nietzsche's basic view of truth as follows:[89]

... Some scholars regard Nietzsche's 1873 unpublished essay, "On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense" ("Über Wahrheit und Lüge im außermoralischen Sinn") as a keystone in his thought. In this essay, Nietzsche rejects the idea of universal constants, and claims that what we call "truth" is only "a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms." His view at this time is that arbitrariness completely prevails within human experience: concepts originate via the very artistic transference of nerve stimuli into images; "truth" is nothing more than the invention of fixed conventions for merely practical purposes, especially those of repose, security and consistence. ...

Separately Nietzsche suggested that an ancient, metaphysical belief in the divinity of Truth lies at the heart of and has served as the foundation for the entire subsequent Western intellectual tradition: "But you will have gathered what I am getting at, namely, that it is still a metaphysical faith on which our faith in science rests—that even we knowers of today, we godless anti-metaphysicians still take our fire too, from the flame lit by the thousand-year old faith, the Christian faith which was also Plato's faith, that God is Truth; that Truth is 'Divine' ..."[90][91]

Moreover, Nietzsche challenges the notion of objective truth, arguing that truths are human creations and serve practical purposes. He wrote, "Truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are."[92] He argues that truth is a human invention, arising from the artistic transference of nerve stimuli into images, serving practical purposes like repose, security, and consistency; formed through metaphorical and rhetorical devices, shaped by societal conventions and forgotten origins:[93]

"What, then, is truth? A mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms – in short, a sum of human relations which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically ..."

Nietzsche argues that truth is always filtered through individual perspectives and shaped by various interests and biases. In "On the Genealogy of Morality," he asserts, "There are no facts, only interpretations."[94] He suggests that truth is subject to constant reinterpretation and change, influenced by shifting cultural and historical contexts as he writes in "Thus Spoke Zarathustra" that "I say unto you: one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star."[95] In the same book, Zarathustra proclaims, "Truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions; they are metaphors that have become worn out and have been drained of sensuous force, coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer as coins."[96]

Heidegger (1889–1976)

[edit]Other philosophers take this common meaning to be secondary and derivative. According to Martin Heidegger, the original meaning and essence of truth in Ancient Greece was unconcealment, or the revealing or bringing of what was previously hidden into the open, as indicated by the original Greek term for truth, aletheia.[97][98] On this view, the conception of truth as correctness is a later derivation from the concept's original essence, a development Heidegger traces to the Latin term veritas. Owing to the primacy of ontology in Heidegger's philosophy, he considered this truth to lie within Being itself, and already in Being and Time (1927) had identified truth with "being-truth" or the "truth of Being" and partially with the Kantian thing-in-itself in an epistemology essentially concerning a mode of Dasein.[99]

Sartre (1905–1980)

[edit]In Being and Nothingness (1943), partially following Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre identified our knowledge of the truth as a relation between the in-itself and for-itself of being - yet simultaneously closely connected in this vein to the data available to the material personhood, in the body, of an individual in their interaction with the world and others - with Sartre's description that "the world is human" allowing him to postulate all truth as strictly understood by self-consciousness as self-consciousness of something,[100] a view also preceded by Henri Bergson in Time and Free Will (1889), the reading of which Sartre had credited for his interest in philosophy.[101] This first existentialist theory, more fully fleshed out in Sartre's essay Truth and Existence (1948), which already demonstrates a more radical departure from Heidegger in its emphasis on the primacy of the idea, already formulated in Being and Nothingness, of existence as preceding essence in its role in the formulation of truth, has nevertheless been critically examined as idealist rather than materialist in its departure from more traditional idealist epistemologies such as those of Ancient Greek philosophy in Plato and Aristotle, and staying as does Heidegger with Kant.[102]

Later, in the Search for a Method (1957), in which Sartre used a unification of existentialism and Marxism that he would later formulate in the Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), Sartre, with his growing emphasis on the Hegelian totalisation of historicity, posited a conception of truth still defined by its process of relation to a container giving it material meaning, but with specfiic reference to a role in this broader totalisation, for "subjectivity is neither everything nor nothing; it represents a moment in the objective process (that in which externality is internalised), and this moment is perpetually eliminated only to be perpetually reborn": "For us, truth is something which becomes, it has and will have become. It is a totalisation which is forever being totalised. Particular facts do not signify anything; they are neither true nor false so long as they are not related, through the mediation of various partial totalities, to the totalisation in process." Sartre describes this as a "realistic epistemology", developed out of Marx's ideas but with such a development only possible in an existentialist light, as with the theme of the whole work.[103][104] In an early segment of the lengthy two-volume Critique of 1960, Sartre continued to describe truth as a "totalising" "truth of history" to be interpreted by a "Marxist historian", whilst his break with Heidegger's epistemological ideas is finalised in the description of a seemingly antinomous "dualism of Being and Truth" as the essence of a truly Marxist epistemology.[105]

Camus (1913–1960)

[edit]The well-regarded French philosopher Albert Camus wrote in his famous essay, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), that "there are truths but no truth", in fundamental agreement with Nietzsche's perspectivism, and favourably cites Kierkergaad in posing that "no truth is absolute or can render satisfactory an existence that is impossible in itself".[106] Later, in The Rebel (1951), he declared, akin to Sartre, that "the very lowest form of truth" is "the truth of history",[107] but describes this in the context of its abuse and like Kierkergaad in the Concluding Unscientific Postscript he criticizes Hegel in holding a historical attitude "which consists of saying: 'This is truth, which appears to us, however, to be error, but which is true precisely because it happens to be error. As for proof, it is not I, but history, at its conclusion, that will furnish it.'"[108]

Whitehead (1861–1947)

[edit]Alfred North Whitehead, a British mathematician who became an American philosopher, said: "There are no whole truths; all truths are half-truths. It is trying to treat them as whole truths that plays the devil".[109]

The logical progression or connection of this line of thought is to conclude that truth can lie, since half-truths are deceptive and may lead to a false conclusion.

Peirce (1839–1914)

[edit]Pragmatists like C. S. Peirce take truth to have some manner of essential relation to human practices for inquiring into and discovering truth, with Peirce himself holding that truth is what human inquiry would find out on a matter, if our practice of inquiry were taken as far as it could profitably go: "The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate, is what we mean by the truth ..."[110]

Nishida (1870–1945)

[edit]According to Kitaro Nishida, "knowledge of things in the world begins with the differentiation of unitary consciousness into knower and known and ends with self and things becoming one again. Such unification takes form not only in knowing but in the valuing (of truth) that directs knowing, the willing that directs action, and the feeling or emotive reach that directs sensing."[111]

Fromm (1900–1980)

[edit]Erich Fromm finds that trying to discuss truth as "absolute truth" is sterile and that emphasis ought to be placed on "optimal truth". He considers truth as stemming from the survival imperative of grasping one's environment physically and intellectually, whereby young children instinctively seek truth so as to orient themselves in "a strange and powerful world". The accuracy of their perceived approximation of the truth will therefore have direct consequences on their ability to deal with their environment. Fromm can be understood to define truth as a functional approximation of reality. His vision of optimal truth is described partly in Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947), from which excerpts are included below.

... the dichotomy between 'absolute = perfect' and 'relative = imperfect' has been superseded in all fields of scientific thought, where "it is generally recognized that there is no absolute truth but nevertheless that there are objectively valid laws and principles".

[...] In that respect, "a scientifically or rationally valid statement means that the power of reason is applied to all the available data of observation without any of them being suppressed or falsified for the sake of the desired result". The history of science is "a history of inadequate and incomplete statements, and every new insight makes possible the recognition of the inadequacies of previous propositions and offers a springboard for creating a more adequate formulation."

[...] As a result "the history of thought is the history of an ever-increasing approximation to the truth. Scientific knowledge is not absolute but optimal; it contains the optimum of truth attainable in a given historical period." Fromm furthermore notes that "different cultures have emphasized various aspects of the truth" and that increasing interaction between cultures allows for these aspects to reconcile and integrate, increasing further the approximation to the truth.

Foucault (1926–1984)

[edit]Truth, says Michel Foucault, is problematic when any attempt is made to see truth as an "objective" quality. He prefers not to use the term truth itself but "Regimes of Truth". In his historical investigations he found truth to be something that was itself a part of, or embedded within, a given power structure. Thus Foucault's view shares much in common with the concepts of Nietzsche. Truth for Foucault is also something that shifts through various episteme throughout history.[112]

Baudrillard (1929–2007)

[edit]Jean Baudrillard considered truth to be largely simulated, that is pretending to have something, as opposed to dissimulation, pretending to not have something. He took his cue from iconoclasts whom he claims knew that images of God demonstrated that God did not exist.[113] Baudrillard wrote in "Precession of the Simulacra":

- The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth—it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true.

- —Ecclesiastes[114][115]

Some examples of simulacra that Baudrillard cited were: that prisons simulate the "truth" that society is free; scandals (e.g., Watergate) simulate that corruption is corrected; Disney simulates that the U.S. itself is an adult place. Though such examples seem extreme, such extremity is an important part of Baudrillard's theory. For a less extreme example, movies usually end with the bad being punished, humiliated, or otherwise failing, thus affirming for viewers the concept that the good end happily and the bad unhappily, a narrative which implies that the status quo and established power structures are largely legitimate.[113]

Other contemporary positions

[edit]Truthmaker theory is "the branch of metaphysics that explores the relationships between what is true and what exists".[116] It is different from substantive theories of truth in the sense that it does not aim at giving a definition of what truth is. Instead, it has the goal of determining how truth depends on being.[117]

Theological views

[edit]Hinduism

[edit]In Hinduism, truth is defined as "unchangeable", "that which has no distortion", "that which is beyond distinctions of time, space, and person", "that which pervades the universe in all its constancy". The human body, therefore, is not completely true as it changes with time, for example. There are many references, properties and explanations of truth by Hindu sages that explain varied facets of truth, such as the national motto of India: "Satyameva Jayate" (Truth alone triumphs), as well as "Satyam muktaye" (Truth liberates), "Satya' is 'Parahit'artham' va'unmanaso yatha'rthatvam' satyam" (Satya is the benevolent use of words and the mind for the welfare of others or in other words responsibilities is truth too), "When one is firmly established in speaking truth, the fruits of action become subservient to him (patanjali yogasutras, sutra number 2.36), "The face of truth is covered by a golden bowl. Unveil it, O Pusan (Sun), so that I who have truth as my duty (satyadharma) may see it!" (Brhadaranyaka V 15 1–4 and the brief IIsa Upanisad 15–18), Truth is superior to silence (Manusmriti), etc. Combined with other words, satya acts as a modifier, like ultra or highest, or more literally truest, connoting purity and excellence. For example, satyaloka is the "highest heaven" and Satya Yuga is the "golden age" or best of the four cyclical cosmic ages in Hinduism, and so on. The Buddha, the 9th incarnation of Bhagwan Vishnu, quoted as such - Three things cannot be long hidden: the sun, the moon and the truth.

Buddhism

[edit]In Buddhism, particularly in the Mahayana tradition, the notion of truth is often divided into the two truths doctrine, which consists of relative or conventional truth and ultimate truth. The former refers to truth that is based on common understanding among ordinary people and is accepted as a practical basis for communication of higher truths. Ultimate truth necessarily transcends logic in the sphere of ordinary experience, and recognizes such phenomena as illusory. Mādhyamaka philosophy asserts that any doctrine can be analyzed with both divisions of truth. Affirmation and negation belong to relative and absolute truth respectively. Political law is regarded as relative, while religious law is absolute.

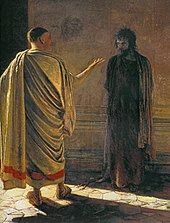

Christianity

[edit]

Christianity has a soteriological view of truth. According to the Bible in John 14:6, Jesus is quoted as having said "I am the way, the truth and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me".

See also

[edit]- Asha

- Confirmation holism

- Contextualism

- Degree of truth

- Disposition

- Eclecticism

- Epistemic theories of truth

- Imagination

- Independence (probability theory)

- Invariant (mathematics)

- McNamara fallacy

- Normative science

- On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense

- Perspectivism

- Physical symbol system

- Public opinion

- Relativism

- Religious views on truth

- Revision theory

- Slingshot argument

- Subjectivity

- Tautology (logic)

- Tautology (rhetoric)

- Theory of justification

- Truth prevails

- Truthiness

- Unity of the proposition

- Verisimilitude

Other theorists

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary, truth Archived 2009-12-29 at the Wayback Machine, 2005

- ^ a b c "Truth". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Alexis G. Burgess and John P. Burgess (2011). Truth (hardcover) (1st ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14401-6. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

a concise introduction to current philosophical debates about truth

- ^ see Holtzmann's law for the -ww- : -gg- alternation.

- ^ Etymology, Online. "Online Etymology". Archived from the original on 13 July 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Geir T. Zoëga (1910), Northvegr.org

- ^ OED on true has "Steadfast in adherence to a commander or friend, to a principle or cause, to one's promises, faith, etc.; firm in allegiance; faithful, loyal, constant, trusty; honest, honourable, upright, virtuous, trustworthy; free from deceit, sincere, truthful" besides "Conformity with fact; agreement with reality; accuracy, correctness, verity; Consistent with fact; agreeing with the reality; representing the thing as it is; real, genuine; rightly answering to the description; properly so called; not counterfeit, spurious, or imaginary."

- ^ a b c d e f Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Supp., "Truth", auth: Michael Williams, pp. 572–573 (Macmillan, 1996)

- ^ Blackburn, Simon, and Simmons, Keith (eds., 1999), Truth, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Includes papers by James, Ramsey, Russell, Tarski, and more recent work.

- ^ Hale, Bob; Wright, Crispin; Miller, Alexander, eds. (1997). A Companion to the Philosophy of Language (1999 reprint ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21326-0. OCLC 40839879.

- Heal, Jane (1997). "13. Radical Interpretation". A Companion to the Philosophy of Language. "Chapter postscript" by Alexander Miller. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 299−323. doi:10.1002/9781118972090.ch13. ISBN 978-1-118-97471-1.

- Richard, Mark (1997). "14. Propositional Attitudes". A Companion to the Philosophy of Language. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 324–356.

- ^ "The PhilPapers Surveys – Preliminary Survey results". The PhilPapers Surveys. Philpapers.org. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Correspondence Theory of Truth", auth.: Arthur N. Prior, p. 223 (Macmillan, 1969). Prior uses Bertrand Russell's wording in defining correspondence theory. According to Prior, Russell was substantially responsible for helping to make correspondence theory widely known under this name.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Correspondence Theory of Truth", auth.: Arthur N. Prior, pp. 223–224 (Macmillan, 1969).

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. 2, "Correspondence Theory of Truth", auth.: Arthur N. Prior, Macmillan, 1969, p. 224.

- ^ "Correspondence Theory of Truth", in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archived 2019-10-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I. Q.16, A.2 arg. 2.

- ^ "Correspondence Theory of Truth", in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archived 2019-10-31 at the Wayback Machine (citing De Veritate Q.1, A.1–3 and Summa Theologiae, I. Q.16).

- ^ See, e.g., Bradley, F.H., "On Truth and Copying", in Blackburn, et al. (eds., 1999),Truth, 31–45.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Correspondence Theory of Truth", auth: Arthur N. Prior, pp. 223 ff. Macmillan, 1969. See especially, section on "Moore's Correspondence Theory", 225–226, "Russell's Correspondence Theory", 226–227, "Remsey and Later Wittgenstein", 228–229, "Tarski's Semantic Theory", 230–231.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Correspondence Theory of Truth", auth: Arthur N. Prior, pp. 223 ff. Macmillan, 1969. See the section on "Tarski's Semantic Theory", 230–231.

- ^ Immanuel Kant, for instance, assembled a controversial but quite coherent system in the early 19th century, whose validity and usefulness continues to be debated even today. Similarly, the systems of Leibniz and Spinoza are characteristic systems that are internally coherent but controversial in terms of their utility and validity.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Coherence Theory of Truth", auth: Alan R. White, pp. 130–131 (Macmillan, 1969)

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Coherence Theory of Truth", auth: Alan R. White, pp. 131–133, see esp., section on "Epistemological assumptions" (Macmillan, 1969)

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Coherence Theory of Truth", auth: Alan R. White, p. 130

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. 5, "Pragmatic Theory of Truth", 427 (Macmillan, 1969).

- ^ a b Peirce, C.S. (1901), "Truth and Falsity and Error" (in part), pp. 716–720 in James Mark Baldwin, ed., Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, v. 2. Peirce's section is entitled "Logical", beginning on p. 718, column 1, and ending on p. 720 with the initials "(C.S.P.)", see Google Books Eprint. Reprinted, Collected Papers v. 5, pp. 565–573.

- ^ a b James, William, The Meaning of Truth, A Sequel to 'Pragmatism', (1909).

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol.2, "Dewey, John", by Richard J. Bernstein, p. 383 (Macmillan, 1969)

- ^ Sahakian, W.S. & Sahakian, M.L., Ideas of the Great Philosophers, New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966, LCCN 66--23155

- ^ a b c Feynman, Richard Phillips (1994) [First published 1965]. The Character of Physical Law. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-679-60127-2.

- ^ May, Todd (1993). Between Genealogy and Epistemology: Psychology, Politics, and Knowledge in the Thought of Michel Foucault. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271027821. OCLC 26553016.

- ^ See, e.g., Habermas, Jürgen, Knowledge and Human Interests (English translation, 1972).

- ^ See, e.g., Habermas, Jürgen, Knowledge and Human Interests (English translation, 1972), esp. Part III, pp. 187 ff.

- ^ Rescher, Nicholas, Pluralism: Against the Demand for Consensus (1995).

- ^ Blackburn, Simon, and Simmons, Keith (eds., 1999), Truth in the Introductory section of the book.

- ^ Richard Kirkham, Theories of Truth: A Critical Introduction, MIT Press, 1992.

- ^ Ramsey, F.P. (1927), "Facts and Propositions", Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume 7, 153–170. Reprinted, pp. 34–51 in F.P. Ramsey, Philosophical Papers, David Hugh Mellor (ed.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1990

- ^ Le Morvan, Pierre. (2004) "Ramsey on Truth and Truth on Ramsey", The British Journal for the History of Philosophy 12(4), pp. 705–718.

- ^ J. L. Austin, "How to Do Things With Words". Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975

- ^ Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Vol. 6: Performative Theory of Truth, auth: Gertrude Ezorsky, p. 88 (Macmillan, 1969)

- ^ "skepticism". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. n.d. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2018. Citing:

- Popkin, R. H. (1968). The History of Skepticism from Erasmus to Descartes (revised ed.).

- Stough, C. L. (1969). Greek Skepticism.

- Burnyeat, M., ed. (1983). The Skeptical Tradition.

- Stroud, B. (1984). The Significance of Philosophical Skepticism.

- ^ "Philosophical views are typically classed as skeptical when they involve advancing some degree of doubt regarding claims that are elsewhere taken for granted." utm.edu Archived 2009-01-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Greco, John (2008). The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-518321-4.

- ^ "Definition of SKEPTICISM". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ Truth and Objectivity, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- ^ Truth as One and Many (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- ^ Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

- ^ Kretzmann, Norman (1968). "IV, section=2. 'Infinitely Many' and 'Finitely Many'". William of Sherwood's Treatise on Syncategorematic Words. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5805-3.

- ^ Smith, Nicholas J.J. (2010). "Article 2.6" (PDF). Many-Valued Logics. Routledge. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Mancosu, Paolo; Zach, Richard; Badesa, Calixto (2004). "9. The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski 1900-1935" §7.2 "Many-valued logics". The Development of Modern Logic. Oxford University Press. pp. 418–420. ISBN 978-0-19-972272-3.

- ^ Garrido, Angel (2012). "A Brief History of Fuzzy Logic". Revista EduSoft. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018., Editorial

- ^ Rescher, Nicholas (1968). "Many-Valued Logic". Topics in Philosophical Logic. Humanities Press Synthese Library volume 17. pp. 54–125. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-3546-9_6. ISBN 978-90-481-8331-9.

- ^ Penelope Maddy; Realism in Mathematics; Series: Clarendon Paperbacks; Paperback: 216 pages; Publisher: Oxford University Press, US (1992); 978-0-19-824035-8.

- ^ Elliott Mendelson; Introduction to Mathematical Logic; Series: Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications; Hardcover: 469 pages; Publisher: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 5 edition (August 11, 2009); 978-1-58488-876-5.

- ^ See, e.g., Chaitin, Gregory L., The Limits of Mathematics (1997) esp. 89 ff.

- ^ M. Davis. "Hilbert's Tenth Problem is Unsolvable." American Mathematical Monthly 80, pp. 233–269, 1973

- ^ Yandell, Benjamin H.. The Honors Class. Hilbert's Problems and Their Solvers (2002).

- ^ Chaitin, Gregory L., The Limits of Mathematics (1997) 1–28, 89 ff.

- ^ Ravitch, Harold (1998). "On Gödel's Philosophy of Mathematics". Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Solomon, Martin (1998). "On Kurt Gödel's Philosophy of Mathematics". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ^ Wang, Hao (1997). A Logical Journey: From Gödel to Philosophy. The MIT Press. (A discussion of Gödel's views on logical intuition is woven throughout the book; the quote appears on page 75.)

- ^ Kripke, Saul. "Outline of a Theory of Truth", Journal of Philosophy, 72 (1975), 690–716

- ^ Keith Simmons, Universality and the Liar: An Essay on Truth and the Diagonal Argument, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993

- ^ Goldblatt, Robert (1983). Topoi, the categorial analysis of logic (revised ed.). Amsterdam: Sole distributors for the U.S.A. and Canada, Elsevier North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-86711-2. OCLC 9622076.

- ^ Scharp, Kevin (2013). "6: What is the Use?". Replacing truth (First ed.). Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965385-0.

- ^ "truth | philosophy and logic". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

Truth is important. Believing what is not true is apt to spoil a person's plans and may even cost him his life. Telling what is not true may result in legal and social penalties.

- ^ Wellman, Henry M., David Cross, and Julanne Watson. "Meta‐analysis of theory‐of‐mind development: the truth about false belief." Child development 72.3 (2001): 655–684.

- ^ Lynch, Michael P. "Alethic functionalism and our folk theory of truth." Synthese 145.1 (2005): 29–43.

- ^ Bueno, Otávio, and Mark Colyvan. "Logical non-apriorism and the law of non-contradiction." The law of non-contradiction: New philosophical essays (2004): 156–175.

- ^ a b c d David, Marion (2005). "Correspondence Theory of Truth" Archived 2014-02-25 at the Wayback Machine in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Asmis, Elizabeth (2009). "Epicurean empiricism". In Warren, James (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism. Cambridge University Press. p. 84.

- ^ O'Keefe, Tim (2010). Epicureanism. University of California Press. pp. 97–98.

- ^ Osman Amin (2007), "Influence of Muslim Philosophy on the West", Monthly Renaissance 17 (11).

- ^ Jan A. Aertsen (1988), Nature and Creature: Thomas Aquinas's Way of Thought, p. 152. Brill, 978-90-04-08451-3.

- ^ Simone van Riet. Liber de philosophia prima, sive Scientia divina (in Latin). p. 413.

- ^ Avicenna: The Metaphysics of The Healing. Translated by Marmura, Michael E. Introduction and annotation by Michael E. Marmura. Brigham Young University Press. 2005. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-934893-77-0.

- ^ Disputed Questions on Truth, 1, 2, c, reply to Obj. 1. Trans. Mulligan, McGlynn, Schmidt, Truth, vol. I, pp. 10–12.

- ^ "Veritas supra ens fundatur" (Truth is founded on being). Disputed Questions on Truth, 10, 2, reply to Obj. 3.

- ^ Rock, Catherine A. (2006). "Forsworn and Fordone: Arcite as Oath-Breaker in the "Knight's Tale"". The Chaucer Review. 40 (4): 416–432. doi:10.1353/cr.2006.0009. JSTOR 25094334. S2CID 159853483.

- ^ Pearsall, Derek (2004). "Medieval Literature and Historical Enquiry". Modern Language Review. 99 (4): xxxi–xlii. doi:10.2307/3738608. JSTOR 3738608. S2CID 155446847.

- ^ Fowler, Elizabeth (2003). "Rev. of Green, A Crisis of Truth". Speculum. 78 (1): 179–182. doi:10.1017/S0038713400099310. JSTOR 3301477.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1781/1787), Critique of Pure Reason. Translated and edited by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), A58/B82.

- ^ a b Kant, Immanuel (1801), The Jäsche Logic, in Lectures on Logic. Translated and edited by J. Michael Young (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 557–558.

- ^ Alberto Vanzo, "Kant on the Nominal Definition of Truth", Kant-Studien, 101 (2010), pp. 147–166.

- ^ "Die Wahrheit ist die Bewegung ihrer an ihr selbst." The Phenomenology of Spirit, Preface, ¶ 48

- ^ On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason, §§ 29–33

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Concluding Unscientific Postscript. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1992

- ^ Watts, Michael. Kierkegaard, Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2003

- ^ Robert Wicks, "Friedrich Nietzsche – Early Writings: 1872–1876" Archived 2018-09-04 at the Wayback Machine, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich; Williams, Bernard; Nauckhoff, Josefine (2001). Nietzsche: The Gay Science: With a Prelude in German Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63645-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (2006). Nietzsche: 'On the Genealogy of Morality' and Other Writings Student Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46121-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1997). Beyond Good and Evil. Dover Publications. p. 46. ISBN 978-0486298689.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1976). The Portable Nietzsche. Penguin Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-0140150629.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1887). On the Genealogy of Morality. Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0199537082.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1883). Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Penguin UK. p. 46. ISBN 9780140441185.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1883). Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Penguin UK. p. 121. ISBN 9780140441185.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin. "On the Essence of Truth" (PDF). aphelis.net. Retrieved 3 October 2023.

- ^ "Martin Heidegger on Aletheia (Truth) as Unconcealment". Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ^ Heidegger, Martin (1962). Being and Time (1st ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackswell. pp. 256–274.

- ^ Sartre, Jean-Paul (1956). Being and Nothingness: An Essay on Phenomenological Ontolgoy (1st ed.). New York: Philosophical Library.

- ^ Sartre, Jean-Paul (2004). The imaginary : a phenomenological psychology of the imagination. Arlette Elkaïm-Sartre, Jonathan Webber. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-64410-7. OCLC 56549324.

- ^ Wilder, Kathleen (1995). "Truth and existence: The idealism in Sartre's theory of truth". International Journal of Philosophical Studies. 3 (1): 91–109. doi:10.1080/09672559508570805.

- ^ Sartre, Jean-Paul (1963). Search for a Method (1st ed.). New York: Knopf.

- ^ Skirke, Christian (28 April 2014), "Jean-Paul Sartre", Philosophy, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/obo/9780195396577-0192, ISBN 978-0-19-539657-7, retrieved 25 February 2023

- ^ Sartre, Jean-Paul (2004). Critique of Dialectical Reason. London: Verso. pp. 15–41.

- ^ Camus, Albert (2020). The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (1st ed.). London: Penguin Group. pp. 14–16.

- ^ Camus, Albert (2013). The Rebel (3rd ed.). London: Penguin Group. p. 180.

- ^ Camus, Albert (2013). The Rebel (3rd ed.). London: Penguin Group. p. 90.

- ^ Alfred North Whitehead, Dialogues, 1954: Prologue.

- ^ "How to Make Our Ideas Clear". Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ John Maraldo, Nishida Kitarô – Self-Awareness Archived 2010-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, in: The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2005 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Foucault, M. "The Order of Things", London: Vintage Books, 1970 (1966)

- ^ a b Jean Baudrillard. Simulacra and Simulation. Michigan: Michigan University Press, 1994.

- ^ Baudrillard, Jean. "Simulacra and Simulations", in Selected Writings Archived 2004-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, ed. Mark Poster, Stanford University Press, 1988; 166 ff

- ^ Baudrillard's attribution of this quote to Ecclesiastes is deliberately fictional. "Baudrillard attributes this quote to Ecclesiastes. However, the quote is a fabrication (see Jean Baudrillard. Cool Memories III, 1991–95. London: Verso, 1997). Editor's note: In Fragments: Conversations With François L'Yvonnet. New York: Routledge, 2004:11, Baudrillard acknowledges this 'Borges-like' fabrication." Cited in footnote #4 in Smith, Richard G., "Lights, Camera, Action: Baudrillard and the Performance of Representations" Archived 2018-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 2, Number 1 (January 2005)

- ^ Asay, Jamin. "Truthmaker Theory". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Beebee, Helen; Dodd, Julian (2005). Truthmakers: The Contemporary Debate. Clarendon Press. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

References

[edit]- Aristotle, "The Categories", Harold P. Cooke (trans.), pp. 1–109 in Aristotle, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London, 1938.

- Aristotle, "On Interpretation", Harold P. Cooke (trans.), pp. 111–179 in Aristotle, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London, 1938.

- Aristotle, "Prior Analytics", Hugh Tredennick (trans.), pp. 181–531 in Aristotle, Volume 1, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London, 1938.

- Aristotle, "On the Soul" (De Anima), W. S. Hett (trans.), pp. 1–203 in Aristotle, Volume 8, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann, London, 1936.

- Audi, Robert (ed., 1999), The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995. 2nd edition, 1999. Cited as CDP.

- Baldwin, James Mark (ed., 1901–1905), Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, 3 volumes in 4, Macmillan, New York.

- Baylis, Charles A. (1962), "Truth", pp. 321–322 in Dagobert D. Runes (ed.), Dictionary of Philosophy, Littlefield, Adams, and Company, Totowa, NJ.

- Benjamin, A. Cornelius (1962), "Coherence Theory of Truth", p. 58 in Dagobert D. Runes (ed.), Dictionary of Philosophy, Littlefield, Adams, and Company, Totowa, NJ.

- Blackburn, Simon, and Simmons, Keith (eds., 1999), Truth, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Includes papers by James, Ramsey, Russell, Tarski, and more recent work.

- Chandrasekhar, Subrahmanyan (1987), Truth and Beauty. Aesthetics and Motivations in Science, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

- Chang, C.C., and Keisler, H.J., Model Theory, North-Holland, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1973.

- Chomsky, Noam (1995), The Minimalist Program, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.