The Pink Panther (1963 film)

| The Pink Panther | |

|---|---|

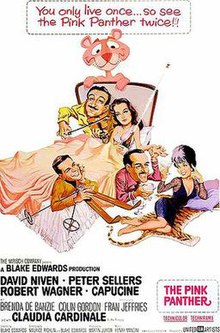

Theatrical release poster by Jack Rickard | |

| Directed by | Blake Edwards |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | Martin Jurow |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Philip Lathrop |

| Edited by | Ralph E. Winters |

| Music by | Henry Mancini |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $10.9 million (US/Canada)[1] |

The Pink Panther is a 1963 American comedy film directed by Blake Edwards and distributed by United Artists. It was written by Maurice Richlin and Blake Edwards. It is the first installment in The Pink Panther franchise. Its story follows Inspector Jacques Clouseau as he travels from Paris to Cortina d'Ampezzo to catch a notorious jewel thief known as "The Phantom" before he is able to steal a priceless diamond known as "The Pink Panther". The film stars David Niven, Peter Sellers, Robert Wagner, Capucine and Claudia Cardinale.

The film was produced by Martin Jurow and was initially released on December 18, 1963, in Italy followed by the United States release on March 18, 1964. It grossed $10.9 million in the United States and Canada.[2] The film received mixed reviews from critics upon its release but would later receive positive reviews and has an 89% approval rating based on 34 votes on Rotten Tomatoes.[3] In 2010, the film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, as being "culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant".[4][5]

Plot

[edit]As a child in Lugash, Princess Dala receives a gift from her father, the Maharajah: the "Pink Panther", the largest diamond in the world. This huge pink gem has an unusual flaw: by looking deeply into the stone, one perceives a tiny discoloration resembling a leaping panther. Twenty years later, Dala has been forced into exile following her father's death and the subsequent military takeover of her country. The new government declares her precious diamond the property of the people and petitions the World Court to determine ownership. However, Dala refuses to relinquish it.

Dala goes on holiday at an exclusive ski resort in Cortina d'Ampezzo. Also staying there is English middle-aged playboy Sir Charles Lytton, who leads a secret life as a gentleman jewel thief called "the Phantom" and has his eyes on the Pink Panther. His brash American nephew George arrives at the resort unexpectedly. George is really a playboy drowning in gambling debts, but poses as a recent college graduate about to enter the Peace Corps so his uncle continues to support his lavish lifestyle.

On the Phantom's trail is French police detective Inspector Jacques Clouseau, whose wife Simone is having an affair with Sir Charles. She has become rich by acting as a fence for the Phantom under the nose of her amorous but oblivious husband. She dodges him while trying to avoid her lover's playboy nephew, who has decided to make the seductive older woman his latest conquest. Sir Charles has grown enamored of Dala (even though he is old enough to be her father) and is ambivalent about carrying out the heist. The night before their departure, George accidentally learns of his uncle's criminal activities.

During a costume party at Dala's villa in Rome, Sir Charles and his nephew separately attempt to steal the diamond, only to find it already missing from the safe. The Inspector discovers both men at the crime scene. They escape during the confusion of the evening's climactic fireworks display. A frantic car chase through the streets of Rome ensues. Sir Charles and George are both arrested after all the vehicles collide with one another in the town square.

Later, Simone informs Dala that Sir Charles wished to call off the theft and asks her to help in his defense. Dala then reveals that she had hid the diamond, knowing in advance from Clouseau of the planned theft. However, the Princess has fallen for Sir Charles and has a plan to save him and George from prison. At the trial, the defense calls as their sole witness a surprised Inspector Clouseau. The barrister asks a series of questions that suggest Clouseau himself could be the Phantom. An unnerved Clouseau pulls out his handkerchief to wipe the perspiration from his brow, and the jewel drops from it.

As Clouseau is taken away to prison, he is mobbed by a throng of enamored women. Watching from a distance, Simone expresses regret, but Sir Charles reassures her that when the Phantom strikes again, Clouseau will be exonerated and plans the Phantom's next heist in South America. Meanwhile, on the way to prison, two Carabinieri express their envy that Clouseau is now desired by so many women. They ask him with obvious admiration how he committed all of those crimes; Clouseau considers his newfound fame and replies, "Well, you know... it wasn't easy."

The film ends after the police car carrying Clouseau to prison runs over a traffic warden: the cartoon Pink Panther from the animated opening credits. He gets back up, just as the police car crashes out of view, holding a card that reads "THEND" before he swipes the letters correctly to read "THE END".

Cast

[edit]- David Niven as Sir Charles Lytton

- Peter Sellers as Inspector Jacques Clouseau

- Robert Wagner as George Lytton, Sir Charles' nephew

- Capucine as Simone Clouseau, Inspector Clouseau's wife

- Claudia Cardinale as Princess Dala

- Colin Gordon as Tucker

- Brenda de Banzie as Angela Dunning

- John Le Mesurier as Defense attorney

- James Lanphier as Saloud

- Guy Thomajan as Artoff

- Fran Jeffries as ski lodge singer

- Michael Trubshawe as Felix Townes, novelist

- Riccardo Billi as Aristotle Sarajos, Greek shipowner

- Meri Welles as Monica Fawn, Hollywood starlet

- Martin Miller as Pierre Luigi, photographer

- Gale Garnett, voice of Princess Dala (uncredited)[6]

Cast notes

- Niven portrayed "Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman", a character resembling the Phantom, in the film Raffles in 1939.

Production

[edit]The film was "conceived as a sophisticated comedy about a charming, urbane jewel thief, Sir Charles Lytton". Peter Ustinov was originally cast as Clouseau, with Ava Gardner as his wife.[7] Janet Leigh turned down the lead female role, as it meant being away from the United States for too long.[8] Audrey Hepburn, Nancy Kwan, and Cyd Charisse were considered to play as Princess Dala before Claudia Cardinale was hired in the role.[9]

Production was originally scheduled to begin at Cinecittà Studios in Rome on November 5, 1962. After Gardner backed out in October 1962 because The Mirisch Company would not meet her demands for a personal staff,[10][9] Ustinov also left the project, delaying the project for several weeks. Blake Edwards cast Sellers to replace Ustinov after meeting him while he was on a weekend vacation in Rome.[7] He also hired Capucine to replace Gardner. The entire cast with the exception of Niven, Wagner, and Cardinale were subsequent recast as well to better fit Sellers and Capucine's new portrayals of their characters. The Mirisch Company subsequently sued Ustinov for $175,000 in damages for breach of contract.[9]

Production finally began at Cinecittà several days after Sellers was cast on November 19, 1962. Filming also took place at the Italian Alpine resort of Cortina d'Ampezzo in January 1963. Principal photography concluded in March 1963 with several days of location shooting in Paris and Los Angeles. According to the DVD commentary by Blake Edwards, the chase scene at the piazza (filmed at Piazza della Repubblica in Rocca di Papa) was an homage to a similar sequence 26 minutes into Alfred Hitchcock's Foreign Correspondent (1940).

The film was initially intended as a vehicle for Niven, as evidenced by his top billing.[11] As Edwards shot the film, employing multiple takes of improvised scenes, it became clear that Sellers, originally considered a supporting actor, was stealing the scenes. This resulted in his central role in all the film's sequels. When presenting at a subsequent Academy Awards ceremony, Niven requested his walk-on music be changed from the "Pink Panther" theme, stating, "That was not really my film."[12][full citation needed]

Fran Jeffries sang the song "Meglio stasera (It Had Better Be Tonight)" in a scene set around the fireplace of a ski lodge. The song was composed by Henry Mancini, with English lyrics by Johnny Mercer and Italian lyrics by Franco Migliacci.[9]

Reception

[edit]The movie was a popular hit, earning estimated North American rentals of $6 million.[13] The movie was shown at the Radio City Music Hall in the first United Artists premiere at a major cinema since 1950.[9] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote: "Seldom has any comedian seemed to work so persistently and hard at trying to be violently funny with weak material"; he called the script a "basically unoriginal and largely witless piece of farce carpentry that has to be pushed and heaved at stoutly in order to keep on the move."[14] Variety was much more positive, calling the film "intensely funny" and "Sellers' razor-sharp timing ... superlative."[15] In a 2004 review of The Pink Panther Film Collection, a DVD collection that included The Pink Panther, The A.V. Club wrote:

Because the later movies were identified so closely with Clouseau, it's easy to forget that he was merely one in an ensemble at first, sharing screen time with Niven, Capucine, Robert Wagner and Claudia Cardinale. If not for Sellers' hilarious pratfalls, The Pink Panther could be mistaken for a luxuriant caper movie like Topkapi ... which is precisely what makes the movie so funny. It acts as the straight man, while Sellers gets to play mischief-maker.[16]

The film holds an approval rating of 89% on the review aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes based on 37 reviews, with an average rating of 7.4/10. The website's critical consensus says: "Peter Sellers is at his virtuosically bumbling best in The Pink Panther, a sophisticated caper blessed with an unforgettably slinky score by Henry Mancini."[17] The American Film Institute listed The Pink Panther as No. 20 in its 100 Years of Film Scores.

Soundtrack

[edit]The soundtrack album for the film, featuring Henry Mancini's score, was released in 1964 and reached No. 8 on the Billboard magazine's pop album chart. It was nominated for Grammy and Academy Awards and was later inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame and selected by the American Film Institute as one of the greatest film scores.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Pink Panther (1963)". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "The Pink Panther". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ The Pink Panther (1963), retrieved 2020-02-14

- ^ Morgan, David (December 28, 2010). "'Empire Strikes Back' among 25 film registry picks". CBS News. CBS Interactive. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ Barnes, Mike (December 28, 2010). "'Empire Strikes Back', 'Airplane!' Among 25 Movies Named to National Film Registry". The Hollywood Reporter. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^

- "The Pink Panther: Articles". TCMDb. Archived from the original on 2014-03-16. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

Claudia Cardinale did not speak English very well when she made this film, so her dialogue was dubbed by Gale Garnett, the Canadian singer-actress whose hit "We'll Sing in the Sunshine" won a Grammy in 1965.

- The Pink Panther at the TCM Movie Database

- "The Pink Panther: Articles". TCMDb. Archived from the original on 2014-03-16. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ a b "The Pink Panther (1964): Overview". Turner Classic Movies. WarnerMedia. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Barnes, David (1997). "Janet Leigh Interview". Retrosellers. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e The Pink Panther at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ Thomas, Bob (November 17, 1962). "Stars' Salaries The Biggest Gripe". The Daytona Beach News-Journal. Associated Press. p. 5. Retrieved September 2, 2010 – via Google News.

- ^ Morley, Sheridan (1985). The Other Side Of The Moon: The Life of David Niven. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780060154707.

- ^ Neal Gabler, opening comments from Reel Thirteen, WNET-TV.

- ^ "Big Rental Pictures of 1964". Variety. Penske Business Media. January 6, 1965. p. 39. Retrieved July 17, 2018. Please note this figure is rentals accruing to distributors not total gross.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (April 24, 1964). "Screen: Sellers Chases a Jewel Thief; Pink Panther' Opens at Music Hall". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ "The Pink Panther". Variety. Penske Business Media. December 31, 1963. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ Tobias, Scott (April 5, 2004). "The Pink Panther Film Collection". The A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ "The Pink Panther (1963)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

Further reading

- Wagner, Robert (2008). Pieces of My Heart: A Life. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780061373312.

External links

[edit]- 1963 films

- 1960s heist films

- American heist films

- 1960s English-language films

- Films directed by Blake Edwards

- Films scored by Henry Mancini

- Films set in Italy

- Films set in fictional countries

- Films shot in Italy

- 1960s French-language films

- 1960s German-language films

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- 1960s Italian-language films

- The Pink Panther films

- United Artists films

- United States National Film Registry films

- 1960s police comedy films

- Films with screenplays by Blake Edwards

- 1963 comedy films

- Films about jewellery

- American films with live action and animation

- 1960s American films

- 1960s British films

- English-language crime comedy films

- Films shot at Cinecittà Studios

- Films shot in Paris

- Films shot in Los Angeles