The Da Vinci Code (video game)

| The Da Vinci Code | |

|---|---|

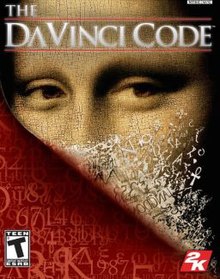

North American PlayStation 2 version cover art | |

| Developer(s) | The Collective |

| Publisher(s) | 2K |

| Producer(s) | Cordy Rierson |

| Designer(s) | Lisa Hoffman |

| Programmer(s) | David Mark Byttow |

| Artist(s) | David R. Donatucci |

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Winifred Phillips |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation 2, Xbox, Windows |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Adventure, puzzle |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Da Vinci Code is a 2006 adventure puzzle video game developed by The Collective and published by 2K for PlayStation 2, Xbox and Microsoft Windows. Although the game was released on the same day that the film of the same name opened in theaters, it is based directly on the 2003 novel by Dan Brown rather than the film. As such, the characters in the game do not resemble nor sound like their filmic counterparts.

The Da Vinci Code received mixed reviews across all platforms. Although some critics praised the game's fidelity to its source material, the majority criticized the graphics and basic gameplay, particularly the melee combat.

Gameplay

[edit]The Da Vinci Code is an action-adventure/puzzle game played from a third-person perspective. The aim of the game, as with both the book and the film, is to locate the Holy Grail. To achieve this goal, the player must gather clues, solve puzzles, and successfully evade or defeat enemies.

Players control both Robert Langdon and Sophie Neveu. Who the player controls during any given level is pre-determined; the player has no choice as to which character to use at any given time in the game. The differences between the two characters are purely for narrative purposes; in terms of gameplay, both characters have the same speed, strength and abilities, can use the same items, and share an inventory.[1]

The majority of the gameplay involves one of three aspects; searching, melee combat and puzzles. When searching locations, the player moves the characters around in a 3D environment viewed from a third-person perspective. When an object or location which can be examined more closely is found, the game switches to first-person mode, and the player can investigate in more detail.[2][3] At this time, clues can be discovered on the object, or more specific objects can be found within the location.[4]

Melee combat is split into two phases. In the first phase, the player approaches an enemy and attempts to punch them, as with most beat 'em up games. If the player successfully hits the enemy, the game enters attack mode. If the player misses and is instead attacked themselves, the game enters defense mode. Both modes are identical insofar as the player must enter a sequence of button presses before the timer runs out. If they do so correctly, they will successfully attack or block the enemy. If they run out of time or press the wrong buttons, they will be attacked or blocked themselves.[5] Players can also push enemies away and attempt to flee from combat,[1][6] and they can attempt to avoid combat altogether by sneaking up behind enemies and knocking them out.[7]

Plot

[edit]The game begins with Silas (voiced by Phil LaMarr) sitting in his chamber, tightening a spiked metal cilice around his leg.[8] He then picks up a handgun and leaves. The game cuts to Robert Langdon (Robert Clotworthy), a Harvard professor of symbology in Paris for a lecture, arriving at the Louvre, where he has been asked to view a crime scene by Cpt. Bezu Fache (Enn Reitel). Jacques Saunière (Neil Ross), Langdon's friend and curator of the museum, has been murdered.[9] In flashback, Silas is shown asking Saunière where something is. Saunière tells him, and Silas responds, "I believe you. The others told me the same," before shooting him.

In the museum, Fache shows Langdon that before he died, Saunière wrote a numeric cipher and a message, "O Draconian Devil! Oh Lame Saint!" in blacklight ink. At this point, Sophie Neveu (Jennifer Hale), a member of the cryptography department arrives, explaining the cipher is part of the Fibonacci sequence, although the numbers are out of order. She then secretly tells Langdon he is in danger, as Fache thinks he is the murderer. In the toilets, she reveals the police have planted a GPS tracking device on Langdon. Neveu tells him that also written in black light ink were the words "PS. Find Robert Langdon." She explains that Saunière was her grandfather and "PS" was his nickname for her; "Princess Sophie." She believes that Saunière included the numerical cipher in the message to insure her involvement in the case.

Langdon throws the GPS device onto a passing car, and most of the police leave the museum to follow. He and Neveu return to the body, and Langdon realizes the numbers are out of sequence to tell them that the letters are also out of sequence; the words are anagrams. He deciphers "Draconian Devil" as "Leonardo da Vinci" and "Oh Lame Saint" as "The Mona Lisa". As they head to the painting, Langdon speculates "PS" could also refer to the Priory of Sion. His theory is strengthened when Neveu remembers seeing the letters together with a fleur-de-lis when she was a child; "PS" combined with a fleur-de-lis is the coat of arms of the Priory. At the Mona Lisa, they find a substitution cipher written in black light ink on the glass around the painting. The clues lead them to Saunière's office, where they listen to a message in which Sister Sandrine of Saint-Sulpice tells Saunière "the floor is broken and the other three are dead." A window is heard smashing and a man says, "Your fate was sealed the moment you stood against Manus Dei." As they continue to follow clues left by Saunière, eventually Neveu concludes they must head to his chateau. She and Robert split up as she heads to the chateau and he heads to Saint-Sulpice.

Once there, he finds a monk attacking a young nun. He knocks the monk out, and the nun, Sister Marguerite (Jane Carr), tells him that Sandrine is dead, killed by Silas, who was looking for something that Sandrine refused to give him. He left moments before the monks arrived, who seemed to be trying to erase evidence of his actions. Langdon concludes the monks are members of Sanctus Umbra, a militant subgroup of Manus Dei.[10] Langdon examines the broken floor at the base of the Gnomon of Saint-Sulpice and finds a stone tablet with Job 38:11 inscribed on it; "Hitherto shalt thou come but no further." He deduces that Silas was misled by Saunière and the others.[11] He heads into the crypt, where he finds a list of Priory Grand Masters, discovering Saunière was the current Master.

Meanwhile, at the chateau, Neveu heads for Saunière's underground grotto. She evades both Silas and the police, and follows a series of clues to find a key with the address of the Depository Bank of Zurich. Meeting up with Langdon, they head to the bank, where they open Saunière's deposit box, finding a cryptex. They then head to Château Villette, the residence of Sir Leigh Teabing (Greg Ellis), Langdon's friend and one of the world's foremost experts on the Holy Grail.[12] Teabing and Langdon explain to Neveu that the Grail is not a cup, but a reference to a woman. Looking at da Vinci's The Last Supper, Teabing explains the image of John is actually Mary Magdalene, to whom the historical Jesus was married. This marriage was suppressed by the early Church, who needed its followers to believe Jesus was divine.[13] Teabing explains that the chalice that held the blood of Christ, the Holy Grail of legend, was Mary herself, as she was pregnant with Jesus' child.[14] At this point, Silas arrives, revealing he murdered Saunière under the orders of "The Teacher." Langdon and Neveu incapacitate him, and with Teabing and his servant Remy (Andres Aguilar), they head to London, taking the unconscious Silas with them.

Landing at Biggin Hill, they head to Temple Church. Langdon and Teabing go inside, but in the courtyard, Neveu sees Remy betray them and send a gang of thugs in after them. Langdon wakes up in a dungeon, but manages to escape, and meets up with Neveu. He tells her Remy is holding Teabing hostage to use him as a bargaining chip for the cryptex. Inside the church, Remy and Silas confront Langdon and Neveu, who flee and head to Westminster Abbey, where Teabing is being held. Once there, they decide they must solve the cryptex to bargain for Teabing's life. Following a series of clues left by Saunière, they do so, but before they can open it, they are captured by Remy. He takes them to Teabing, who reveals himself to be The Teacher. He shoots Remy as he no longer needs him, and reveals Silas has just been arrested for the recent murders. He tells Langdon and Neveu the Priory was supposed to make public the contents of the cryptex on the eve of the New Millennium, but Saunière decided against it. As such, Teabing determined to reveal the documents himself. He asks Langdon and Neveu to join him in revealing the truth about Mary Magdalene, but they refuse and Langdon destroys the cryptex. Teabing is arrested as he laments the truth being lost forever.

However, Langdon had removed the document before destroying the device. Following the clue contained within, he and Neveu head to Rosslyn Chapel. There, they find a family tree for the Saint-Clair family, running back to the Merovingian dynasty. In a series of documents, they learn that when Sophie's family were killed in a car accident, newspaper reports said that all of the family were killed; mother, father, and two children. The reports also state the family's name was Saint-Clair. Langdon realizes the truth; Neveu survived the accident, and the Priory put out the story she was dead to protect her, as she is a living blood relative of Jesus. Neveu's grandmother then arrives, explaining the family changed its name for protection. She introduces Neveu to her brother, who also survived the crash; he came to Scotland whilst Neveu went to France with Saunière. Neveu's grandmother then tells Langdon that the grail is not in Rosslyn, it is in France. He realizes the clue in the cryptex didn't point to Rosslyn but to the Rose Line in Paris. He says goodbye to Neveu and heads to France, finally understanding the grail lies beneath the Louvre Pyramid.

Development

[edit]The game was announced on November 2, 2005, with Sony Pictures revealing The Collective were developing and 2K Games publishing, with plans for a simultaneous release with the upcoming film directed by Ron Howard. Sony also stated, however, that the game was based on the book, not the film. It was also announced that Charles Cecil, creator of the Broken Sword series, was working as a consultant on the puzzles in the game.[15][16]

An 80% complete version of the game was shown to gaming websites in April 2006. The "Struggle System" melee combat mode was demonstrated, as were the various locations and the recreations of real works of art. It was also revealed the game would include levels and locations not featured in the novel, although it would adhere to Brown's overall plot. IGN's Douglass C. Perry wrote of the demo, "the game demoed well, with clean sharp graphics for the current gen systems, offering interesting dialog, and a premise that stands out from many other titles in the adventure genre. The linear, story-based title intrigued us with its focus on art and culture, but it backed the heady concepts up with smart puzzles, a fun grappling system, and good gameplay. Despite the rage for everything next-gen these days, The Da Vinci Code, a game that ordinarily would smack of movie-license dog food, instead is a refreshing re-thinking on the rather worn adventure genre."[17] The game was also shown at E3 2006 in May.[18][19] It was released in North America on May 16, 2006,[20] and in Europe on May 19.[21]

Mobile phone adaptations

[edit]Announced a month before the main game was a two-part mobile phone adaptation of the novel, developed by Kayak Interactive.[22] The first part, The Da Vinci Code: The Quest Begins, was released on April 14, 2006 prior to both the main game and the film.[23] The adaptation took the form of an isometric puzzle game.[24] The second part of the game was never made. Another mobile game, The Da Vinci Code 3D, was announced in April 2006 and released in May 2006. It was developed by Southend Interactive.[25][26]

Music

[edit]The original music of The Da Vinci Code video game was composed by Winifred Phillips. The game's music was praised by several reviewers. Jeff Hall of the music review site ScreenSounds called it "a fine piece of contemporary action scoring."[27] Jonathan Fildes of BBC News wrote, "the accompanying music lends a suitably ethereal atmosphere to proceedings."[3] Juan Castro of IGN described it as "moody, atmospheric and decidedly creepy. It's the right kind of music for slow-paced puzzle solving."[1] JP Hurh of Game Revolution wrote, "the ambient music is properly tense and sets the mood."[4]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | PS2 | Xbox | |

| Metacritic | 53/100[28] | 54/100[29] | 52/100[30] |

| Publication | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | PS2 | Xbox | |

| 4Players | 60/100[39] | 60/100[39] | 60/100[39] |

| Eurogamer | 5/10[31] | ||

| Gamekult | 3/10[43] | ||

| GameRevolution | D[4] | D[4] | |

| GameSpot | 6.5/10[6] | 6.5/10[32] | 6.5/10[33] |

| GameSpy | |||

| IGN | 4.5/10[1] | 4.5/10[1] | 4.5/10[1] |

| Jeuxvideo.com | 10/20[40] | 10/20[41] | 10/20[42] |

| Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine | |||

| Official Xbox Magazine (US) | 3/10[37] | ||

| PC Gamer (US) | 45%[38] | ||

| JeuxActu | 7/20[44] | 7/20[45] | 7/20[46] |

The Da Vinci Code received mixed reviews across all three platforms. The PlayStation 2 version holds an aggregate score of 54 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on forty-three reviews,[29] the Xbox version 52 out of 100, based on thirty-four reviews,[30] and the PC version 53 out of 100, based on twenty-five reviews.[28]

IGN's Juan Castro gave the all versions a 4.5 out of 10,[1] writing, "it borrows a riveting story of conspiracy and murder, yet gets bogged down by sloppy gameplay. It even has a few interesting mechanics here and there, but these feel underdeveloped and haphazardly thrown in." He was highly critical of the melee combat, and concluded "as a videogame, The Da Vinci Code captures a fraction of the intrigue from the best-selling novel. It weaves an interesting tale of conspiracy and corruption, but the gameplay simply doesn't back it up. It doesn't offer enough puzzle variety for serious adventure fans, and the combat will irritate or bore most action aficionados."[1]

GameSpy's David Chapman scored the Xbox and PlayStation versions 2 out of 5. He was highly critical of the graphics; "the only thing stiffer than the acting is the character animations. The characters move with all the grace of a three-toed sloth." He praised the puzzles, but was critical of the combat system, and concluded "on the whole the game is a pretty bland and uninspiring attempt to cash in on a successful franchise. The game's poor presentation and frustrating combat system make the mystery behind The Da Vinci Code one that most gamers would be better off leaving unsolved."[34][35]

Game Revolution's JP Hurh gave the PlayStation 2 and Xbox versions a D, citing a "multitude of glitches and unintuitive programming missteps. Odd tics include the game freezing when you try to use certain weapons, an essential clue being invisible and the inability to go through doors or interact with objects when you are carrying something." He was also highly critical of the enemy AI and the melee combat.[4]

Eurogamer's James Lyon gave the PC version 5 out of 10. Like most critics, he was critical of the combat system, writing "the real problem with The Da Vinci Code is that it doesn't really know who to appeal to. The fighting and sneaking are so inharmoniously overlaid as to render them an irritating chore for those who just want to solve puzzles, yet they're also so poorly done that they're hard to put up with even if you did want them." He felt the game captured the tone of the novel well, but concluded "The Collective appears to have over-egged the pudding a little, putting far too much needless emphasis on repetitive and increasingly tedious action elements to the detriment of the already unpolished adventuring. In trying to fulfill the needs of what gamers want as well as Da Vinci Code fans, The Collective has ended up with a game that ultimately proves only half satisfying to either and great to none."[31]

Most positively, GameSpot's Greg Mueller enjoyed The Da Vinci Code as "a challenging and varied gameplay experience that will satisfy the amateur cryptographer in everyone". He praised the game's integrity to the novel, but, like most critics, was critical of the combat system. He concluded that "the biggest fault of The Da Vinci Code is the overall presentation. The voice actors sound completely flat and disinterested in the dialogue, the character animations are all jerky and unnatural looking, and there are even a few frustrating bugs that make the game feel unfinished."[6][32][33]

Non video-game publications also gave the game a poor reception. BBC News' Jonathan Fildes referred to the PlayStation 2 version as a "frustrating movie tie-in, with endless cutscenes and patchy gameplay. At times it feels tedious, and at others like the ancient mystery is being played out in real time." He argued that "the vast majority of play involves aimlessly wandering around churches, art galleries and stately homes hoping to stumble across an object of interest."[3] Charles Herold of The New York Times gave the game an average review and stated, "because I like puzzles, I enjoyed much of Da Vinci despite its flaws. But there are many of them, and the game's sloppy implementation can be seen in a number of questionable design decisions."[47] Chris Dahlen of The A.V. Club was much less impressed, giving the game a C− and writing "the combat mechanism is an abomination."[48] Matt Degen of the Detroit Free Press was one of the few critics who was impressed with the game, scoring it 3 out of 4, and stating, "You'll spend plenty of time cracking anagrams and other codes, and they aren't child's play, either. There's some combat, too, which, while feeling a little out of place, does provide for variation in the game."[49]

Sales

[edit]The game was met with poor sales figures. In the UK, it debuted at #12 in the sales charts across all systems.[50] It sold slightly better in its second week, climbing up to #8.[51] The game sold less than 20,000 units.[52]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Castro, Juan (May 23, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review". IGN. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Fried, Dave (2006). "Investigation". The Da Vinci Code PlayStation 2 Manual (UK). 2K Games. p. 10. SLES-54031.

- ^ a b c Fildes, Jonathan (May 23, 2006). "Da Vinci Code game disappoints". BBC News. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Hurh, JP (June 2, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review". Game Revolution. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Fried, Dave (2006). "Combat". The Da Vinci Code PlayStation 2 Manual (UK). 2K Games. pp. 13–14. SLES-54031.

- ^ a b c Mueller, Greg (May 22, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review (PC)". GameSpot. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Shoemaker, brad (April 17, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Impressions - Unraveling the Mystery". GameSpot. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ The Collective. The Da Vinci Code. 2K Games. Level/area: St. Sulpice.

Corporal Mortification: The practice of inflicting pain on themselves to avoid the pleasures of the flesh and become closer to God spread early within the sect of Manus Dei. [One such practice] is a cilice or spiked chain that they wear on their upper tight for several hours of the day. This cuts into the flesh leaving small holes and deters them from impure thoughts.

- ^ Fried, Dave (2006). "Characters". The Da Vinci Code PlayStation 2 Manual (UK). 2K Games. p. 4. SLES-54031.

A Professor of Symbology at Harvard University, Mr. Langdon is not foreign to danger and mystery, as some of his previous adventures have brought him close to ancient conspiracies and assassination attempts on his life. It's no wonder that intrigue follows wherever he goes. Langdon came to Paris to give a lecture at the American University of Paris on the power of symbols. While [in Paris] he was supposed to meet with Jacques Saunière to discuss an unknown matter at Saunière's behest, however, a shocking turn of events brings Robert to Saunière, but not as expected.

- ^ The Collective. The Da Vinci Code. 2K Games. Level/area: St. Sulpice.

Sanctus Umbra, Holy Shadow: The Seedy underbelly of Manus Dei, Sanctus Umbra is only a whispered tale passed on as a legend from the early 1930s. Rumors speak of a group of monks trained by Manus Dei in the ways of the ancient Hassassins (or Assassins) from their youth. Their ability to blend with shadows is said to be uncanny, and their thirst to inflict God's vengeance, insatiable.

- ^ The Collective. The Da Vinci Code. 2K Games. Level/area: St. Sulpice.

Job 38:11: This doesn't lead to another clue, in fact it would seem quite the contrary. This is a dead end and whoever broke through the floor and discovered the stone tablet must have been quite enraged. It is likely that the assailant was misled intentionally.

- ^ Fried, Dave (2006). "Characters". The Da Vinci Code PlayStation 2 Manual (UK). 2K Games. p. 5. SLES-54031.

The author of over a dozen books on Grail Lore, Leigh Teabing is a world-renowned expert on history of the Holy Grail. Leigh was diagnosed with polio at age nine and was forced to use crutches the rest of his life. He spent several years traveling to famous Grail sites throughout Europe. He obtained a first-class honors degree in History before moving on to Cambridge University to complete his PhD. After purchasing Château Vilette, Teabing retired to focus on his life's passion, the quest for the Holy Grail.

- ^ The Collective. The Da Vinci Code. 2K Games. Level/area: Château Villette.

Mary Magdalene: According to some, Mary Magdalene was the unfortunate victim of a smear campaign launched by the early Church to cover up the dangerous secret of her being the wife of Jesus.

- ^ The Collective. The Da Vinci Code. 2K Games. Level/area: Château Villette.

Jesus' Bloodline: History would have us believe that Jesus was poor and that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute, though there is overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Jesus was of the House of David, a descendant of King Solomon, the King of the Jews. Mary was of the House of Benjamin, also of royal descent. By marrying into the powerful House of Benjamin, Jesus fused two royal bloodlines, creating a potent political union with the potential of making a legitimate claim to the throne and restoring the line of kings as it was under Solomon. The legend of the Holy Grail is a legend about royal blood. When Grail legend speaks of "the chalice that held the blood of Christ," it speaks, in fact, of Mary Magdalene, the female womb that carried Jesus' royal bloodline.

- ^ Adams, David (November 2, 2005). "Da Vinci Coded for Consoles". IGN. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ Sinclair, Brendan (November 2, 2005). "2K Games to input Da Vinci Code". GameSpot. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ Perry, Douglass C. (April 14, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code". IGN. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ Perry, Douglass C. (May 10, 2006). "E3 2006: The Da Vinci Code". IGN. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ Sinclair, Brendan (May 10, 2006). "E3 06: 2K Games visitors seek Prey". GameSpot. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ^ "Shippin' Out May 15–19: New Super Mario Bros., X-Men". GameSpot. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ Hatfield, Daemon (May 19, 2006). "Da Vinci Code Now Crackable". IGN. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ "Kayak Cracks the Code". IGN. October 18, 2005. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ "The Da Vinci Code: The Quest Begins". IGN. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (April 14, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code: The Quest Begins Review". IGN. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (April 14, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code 3D". IGN. Ziff Davis. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ McCutcheon, David (May 17, 2006). "E3 2006: Da Vinci Code 3D". IGN. Ziff Davis. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Hall, Jeff (June 6, 2006). "CD Review: The Da Vinci Code Game Score". ScreenSounds. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Da Vinci Code (PC)". Metacritic. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Da Vinci Code (PlayStation 2)". Metacritic. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Da Vinci Code (Xbox)". Metacritic. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Lyon, James (May 30, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review (PC)". Eurogamer. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Mueller, Greg (May 22, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review (PS2)". GameSpot. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Mueller, Greg (May 22, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review (Xbox)". GameSpot. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Chapman, David (May 19, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review (PS2)". GameSpy. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Chapman, David (May 19, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review (Xbox)". GameSpy. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ Varanini, Giancarlo (August 2006). "The Da Vinci Code Review (PS2)". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. p. 76.

- ^ "The Da Vinci Code Review (Xbox)". Official Xbox Magazine. August 2006. p. 82.

- ^ "The Da Vinci Code Review (PC)". PC Gamer: 94. September 2006.

- ^ a b c Jörg Luibl (May 18, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code: The Da Vinci Code - Review, Action-Adventure, Xbox, PlayStation 2, PC". 4Players. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Jihem (Jean-Marc Wallimann) (May 19, 2006). "Test de Da Vinci Code sur PC par jeuxvideo.com". JeuxVideo.com. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Jihem (Jean-Marc Wallimann) (May 19, 2006). "Test de Da Vinci Code sur PS2 par jeuxvideo.com". JeuxVideo.com. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Jihem (Jean-Marc Wallimann) (May 19, 2006). "Test de Da Vinci Code sur Xbox par jeuxvideo.com". JeuxVideo.com. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Thomas Méreur (May 24, 2006). "Test: Da Vinci Code PS2: Léonard m'a tuer". Gamekult. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Maxime Chao. "Test The Da Vinci Code sur PC". JeuxActu. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Maxime Chao. "Test The Da Vinci Code sur PlayStation 2". JeuxActu. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Maxime Chao. "Test The Da Vinci Code sur Xbox". JeuxActu. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Herold, Charles (June 1, 2006). "If You Want a Story While Playing Da Vinci, Read the Book". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ Dahlen, Chris (June 7, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ Degen, Matt (June 18, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ Elliott, Phil (May 23, 2006). "UK game charts: May 13–20". GameSpot. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ Elliott, Phil (May 31, 2006). "UK game charts: May 21–27". GameSpot. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ Baertlein, Lisa (July 13, 2006). "Film, video game union not always fruitful". Vancouver Sun. p. 44. Retrieved March 15, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- 2006 video games

- 2K games

- Adventure games

- Detective video games

- Mobile games

- PlayStation 2 games

- Puzzle video games

- Single-player video games

- The Collective (company) games

- The Da Vinci Code

- Video games about police officers

- Video games based on novels

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games featuring female protagonists

- Video games scored by Winifred Phillips

- Video games set in France

- Video games set in Switzerland

- Video games set in the United Kingdom

- Video games set in London

- Windows games

- Xbox games