The Bunker (book)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2021) |

| |

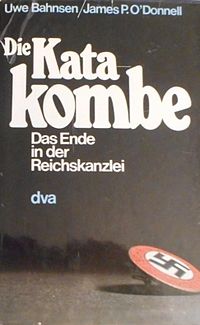

| Authors | James P. O'Donnell Uwe Bahnsen |

|---|---|

| Original title | Die Katakombe – Das Ende in der Reichskanzlei |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Hitler's last days in the Führerbunker |

| Publisher | Deutsche Verlagsanstalt (DVA) |

Publication date | 1975 |

| Publication place | Germany |

Published in English | 1978 (Houghton Mifflin) |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 436 |

| ISBN | 3-421-01712-3 |

| OCLC | 1603646 |

The Bunker (German: Die Katakombe), also published as The Berlin Bunker, is a 1975 account, written by American journalist James P. O'Donnell and German journalist Uwe Bahnsen, as to the history of the Führerbunker in 1945, as well as the last days of German dictator Adolf Hitler. The English edition was first published in 1978. Unlike other accounts O'Donnell focused considerable time on other, less-famous, residents of the bunker complex. Additionally, unlike the more academic works by historians, the book takes a journalistic approach. The book was later used as the basis for a 1981 CBS television film of the same name.

Creation

[edit]During World War II, O'Donnell worked in the U.S. Army Signal Corps. On July 1, 1945, he was mustered out and immediately took a position as German bureau chief for Newsweek magazine. On July 4, he arrived in Berlin with instructions to get details on Hitler's last days, as well as information on Eva Braun.

Soon after arriving, he traveled to the bunker complex, which was mainly overlooked by troops (who were more interested in the Reich Chancellery). He found it guarded by two Red Army soldiers, and for the price of two packs of cigarettes, he gained access to it. He found the bunker complex a flooded, cluttered, stinking mess.

Ironically (and essential, given his later work), the bunker had not, even at this late point, been systematically investigated by the Russians. Lying around for anyone to pick up were such historic items as Hitler's appointment book, Martin Bormann's personal diary, the battle log for Berlin, and segments of Joseph Goebbels' diary. Right in front of O'Donnell, a British colonel took as a "war souvenir" a blueprint for a reconstruction of Hitler's hometown Linz, in Austria. This historic document (brooded over by Hitler during his last days) ended up over the colonel's fireplace in Kent.

As the new bureau chief, O'Donnell wrote about developments, such as the Russian discovery and identification (after several mistakes) of Hitler's body in mid-May of the same year. In August, he came upon a strange sight - the Russians were apparently making a documentary reconstructing Hitler's final days.

Although the bunker complex fell within the Soviet Union controlled sector of Berlin, and many of the survivors were captured by the Soviets, it was the Western powers who revealed the first accurate account of Hitler's death. The British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, on November 1, held a press conference (covered by O'Donnell) where he revealed the generally accepted theory of Hitler's death. While O'Donnell agreed with Trevor-Roper's account save for some minor details (and, in The Bunker, continues to agree with it), he was unsatisfied with this account. Some reasons he gave were:

- Trevor-Roper had access to only two witnesses - Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, and Else Krüger, Bormann's secretary. When he wrote The Last Days of Hitler the following year, he had access to only two more witnesses - Hitler secretary Gerda Christian and Hitler Youth leader Artur Axmann.

- The vast majority of the major witnesses were taken prisoner by the Soviets and, without being charged with any crimes, spent the next ten years in Soviet captivity. Because the Soviets kept denying that Hitler was really dead, they refused to release their interrogation notes to the other Allies.

- Accounts of the bunker centered on major figures, such as Hitler and Goebbels, while paying scant attention to more minor figures. Usually, such accounts stopped after the death of Hitler (or Goebbels). Except for people looking for Bormann (who, for many years, was thought to have survived), nobody bothered writing an account of the "bunker breakout" after Goebbels' death.

In 1969, O'Donnell met Albert Speer, who had just published his memoirs (he wrote an article on Speer for Life, published in 1970). At this point, O'Donnell realized that many of the aforementioned witnesses had long since been released by the Soviets. He began to track them down.

Over the next six years, O'Donnell narrowed his list of witnesses to about 50, and embarked on a project to collate their stories. He usually had these witnesses read his work to verify its authenticity. The book was the result.

Witnesses

[edit]While O'Donnell had 50 witnesses, some saw more than others. Below is a rough list of his main sources. He singled out these sources by eliminating individuals who never saw Hitler after April 22, 1945.

- Albert Speer, the Nazi Minister of Armaments

- Gerda Christian, one of Hitler's secretaries

- Traudl Junge, another of Hitler's secretaries

- Else Krüger, Bormann's secretary

- Erich Kempka, chauffeur

The following observers were captured by the Soviets and held for a decade, and were thus unavailable for many of the initial accounts of Hitler's death.

- Dr. Ernst-Günther Schenck, physician and operator of a casualty station in the Reich Chancellery

- Hans Baur, Hitler's personal pilot

- Johannes Hentschel, mechanic in charge of bunker's electricity and water supply

- Wilhelm Mohnke, Waffen-SS general

- Otto Günsche, Hitler's personal SS adjutant

- Rochus Misch, the Führerbunker telephone/radio operator

While most people were cooperative, a few didn't speak to O'Donnell. Johanna Wolf, another Hitler secretary, declined to talk since she was a "private" secretary. Albert Bormann, Martin Bormann's brother, also refused to cooperate because of family connections. Other people who had been close to Hitler in the final days, most notably Ambassador Walther Hewel, committed suicide after the break-out attempt. More witnesses died in Soviet captivity, such as Dr. Werner Haase, the last physician to attend Hitler, who had already been gravely ill with tuberculosis in April 1945.

Timeline and overview

[edit]O'Donnell established the following timeline, which corresponds with most other accounts of the bunker.

- January 16, 1945. Hitler returns to Berlin and enters the bunker.

- March 19. Speer visits Hitler in an attempt to stop his "scorched earth" policy. He fails, but later goes on to sabotage the programme.

- April 12. American and British troops stop marching towards Berlin, allowing the Soviets free rein, much to the horror of the bunker inhabitants. Also, Franklin D. Roosevelt dies, creating a short-lived euphoria among top Nazis.

- April 15. Eva Braun arrives at the bunker.

- April 20. Hitler's 56th birthday. In a short, one-hour ceremony, Nazi leaders such as Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, gather in Berlin to celebrate, then leave immediately afterwards, never to see Hitler again.

- April 22. Hitler suffers a nervous breakdown and finally admits that Germany will lose the war. He transfers most of the bunker staff to Berchtesgaden, and allows the German High Military Command (under Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl) to leave, as well. He resolves to commit suicide, although a visit from Goebbels apparently causes him to hold off on this for a few days. Magda Goebbels brings all six of her children to live in the Vorbunker.

- April 23. Hitler expels Göring from the Nazi Party after an apparent misunderstanding.

- April 24. Speer returns to say good-bye to Hitler, Braun, and the Goebbels.

- April 28. Hitler learns (via a newswire) of Himmler's attempt to betray him and negotiate a separate peace treaty with the western Allies. Hitler expels Himmler from the Nazi Party and SS, and has his SS FHQ representative, Hermann Fegelein, shot.

- April 29. Hitler marries Braun shortly after midnight. He dictates his last will and testament.

- April 30. In the afternoon, Hitler and Eva Braun hold a farewell ceremony and commit suicide together in the Führerbunker. Their bodies are burned outside in the Reich Chancellery garden.

- May 1. Magda Goebbels drugs her six children, then kills them with cyanide. Afterwards, Joseph and Magda Goebbels commit suicide together outside the bunker complex. Their bodies are inexpertly burned.

- May 1–2. The breakout. The remaining members of the bunker staff escape in separate groups, each to a different fate.

- May 2. Around noon, Soviet troops first enter the bunker complex, finding Johannes Hentschel the sole remaining occupant.

Some of the above dates can be confusing, as Hitler kept unusual hours - he typically slept until late in the morning, went to bed around dawn, and held his military conferences around midnight or later.

Methodology and controversy

[edit]O'Donnell based the book on interviews. When witnesses disagreed, he evaluated them based on the "reliability" of their other statements, the agreement/disagreement with other witnesses, and with his intuition. Many critics (especially those from academic backgrounds) have taken issue with this methodology. Anticipating this, O'Donnell wrote in the prologue:

Just how close this composite account comes to historical truth, to the kind of documentation an academic historian insists on, I simply cannot say. Nor is it overly important to my purpose. I am a journalist, not a historian. I ring doorbells; I do not haunt archives. What I was looking for is what I believe many people look for, psychological truth.

O'Donnell asserted that his method - interviewing the witnesses - is superior to the methods used by academics, noting that much of the written documentation was burned or otherwise destroyed in the final days of the war. Also, written accounts do not allow the writer to "read" a person's expression. O'Donnell even noted that many of the people he interviewed, to make a point, would literally "act out" scenes, a touch not found in historical archives.

Furthermore, he disputed the reliability of the interrogations of witnesses in 1945, which are used as primary sources by most historians. He argued that these interrogations, because of the recent occurrence of the bunker events, the end of the war, and worries over possible criminal charges, were about as accurate as "asking the shell-shocked to describe exactly the burst of artillery." Moreover, many witnesses admitted that they either lied or withheld information during their 1945 interviews, mainly due to pressure from their interrogators (this was especially true of those captured by the Soviets). O'Donnell argued that the witnesses needed time to "digest" their experiences.

However, many critics dispute whether this method was the most reliable. The most cited example was O'Donnell's complete acceptance of Albert Speer's claim to have tried to assassinate Hitler. While many professional historians dispute this claim due to lack of evidence, O'Donnell wrote about it unquestioningly. It is arguable that, if one compares the accounts written in The Bunker with those in Inside the Third Reich, that O'Donnell presents the supposed assassination attempt as more dramatic and purposeful. Admittedly, O'Donnell befriended Speer, and interviewed him 17 times for the book, more than any other witness.

O'Donnell also used hearsay evidence. He used Dr. Schenck for this on numerous occasions, first to discuss Hitler's health (since Hitler's personal SS physician, Haase, died in Russian captivity), and to discuss Hitler's final conversation with his friend Walther Hewel (who committed suicide right in front of Schenck).

O'Donnell states other theories of the bunker events, some of which are criticized because of the above methodology. To name a few:

- He held that the Soviets botched the investigation into Hitler's death. As he saw firsthand, the Soviets did not properly evaluate the "crime scene." Also, in his capacity as a Berlin journalist, he argued that either paranoia or a desire to embarrass the West led Joseph Stalin to deny Hitler's death, and with it, to deny the May 15, 1945 autopsy of Hitler's corpse, which was verified by dental records. O'Donnell holds that whatever remains of Hitler still existed by this date were cremated and scattered, and that any parts of the corpse the Soviets claimed to have afterwards were fabricated to satisfy Stalin. According to contemporary historians, such as Ian Kershaw, the corpses of Braun and Hitler were thoroughly burned when the Red Army found them, and only a lower jaw with dental work could be identified as Hitler's remains.[1]

- He holds that Magda Goebbels was alone responsible for the deaths of her children, although someone must have given her the cyanide, and her husband was supportive of the act. He bases this on Madga's personal correspondence, as well as interviews with the survivors. Some historians do not believe Magda Goebbels was capable of those actions alone.

- From his interviews, he concludes that Hitler did indeed die from shooting himself in the head while simultaneously biting into a cyanide capsule. For the ones who claim this type of suicide was near impossible, he sardonically pointed to Walther Hewel's suicide a few days after Hitler's death. Hewel killed himself in the same way, after receiving the same instructions Dr. Haase gave Hitler.[2]

- He claims that nobody heard the shot that killed Hitler. Whenever he asked witnesses who were standing by the double doors to Hitler's study, which were thick enough to muffle such a sound, they claimed they heard nothing. He put forth that ones who did make this claim in 1945 withdrew it, saying that Allied interrogators pressured them into saying it. He contends that some people who claim to have heard a shot were not even present at the scene.

One of the most unusual claims made by O'Donnell involve the death of Hermann Fegelein. Witnesses claimed that he was killed partly because Hitler suspected his mistress at the time was a spy. O'Donnell created a theory out of this, and makes the claim that Fegelein's mistress actually was a spy, possibly a Hungarian working for British intelligence. However, he could not uncover evidence to support his theory.

Breakout

[edit]O'Donnell's main contribution to Führerbunker literature was his account of the "breakout" that occurred on the night of May 1–2, 1945 - no other historian (or writer) attempted to describe this event before him. He devotes two chapters to it.

The survivors divided into groups (some men, including General Hans Krebs, stayed behind to commit suicide). The groups left on the evening of May 1, each waiting a period of time after the others left. Their plan was to head underground, in the city's subway line, to emerge to the northwest, outside of the Russian-occupied zone of Berlin. The three main groups were:

- Group 1, led by Wilhelm Mohnke. This group awkwardly made its way north to a German army hold-out on the Prinzenallee, and included Dr. Schenck and the female secretaries. The secretaries, upon reaching the outpost, broke off with the help of a Luftwaffe lieutenant. While Junge was later held for several months as the "personal prisoner" of a high-ranking Russian officer,[3] Gerda Christian and Else Krüger, smuggled across Soviet-occupied territory by sympathetic British soldiers, eventually made it to the British/American lines; Krüger, questioned extensively about her then-"missing" boss, later married one of her interrogators. Mohnke and several other men stayed and were captured by the Russians, then treated to dinner with General Vladimir Alexei Belyavski, who tried to get them drunk with vodka to get information on Hitler's death. They didn't talk, and were shipped off to Moscow.

- Group 2, led by Johann Rattenhuber. This group made it to Invalidenstraße northwest of the bunker, but many of its members were captured by the Russians.

- Group 3, led by Werner Naumann, and is most notable for including Martin Bormann. This group completely missed a turn off Friedrichstraße and walked right into Russian gunfire. Bormann and his companion, Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger, were almost certainly intoxicated, and apparently committed suicide with cyanide capsules after realizing the group had run into trouble (this was confirmed by the 1972 discovery of their bodies, which was verified by DNA tests in 1998).[4] Most surviving members of this group were captured by Soviet army troops. Hans Baur, Hitler's pilot, was severely wounded and almost committed suicide. Instead, he was captured, and the Russians put him through many brutal interrogations based on speculation that he might have flown Hitler or Bormann to safety at the last minute.

Misch and Hentschel remained behind in the bunker. Misch left on the morning of May 2, but was soon captured by the Russians. Hentschel stayed in the bunker, while some female Soviet army officers looted Eva Braun's room around noon before he too was taken by the Russians and flown to Moscow.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- O'Donnell, James Preston; Uwe Bahnsen (1975). Die Katakombe – Das Ende in der Reichskanzlei. Stuttgart, Germany: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. p. 436. OCLC 1603646.

- O'Donnell, James Preston (1978). The Bunker: The History of the Reich Chancellery Group. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-395-25719-7.

- ^ Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography, W. W. Norton & Company, p. 958

- ^ O'Donnell (2001) [1978], pp. 322–323 "... we have a fair answer...to the version of ...Russian author Lev Bezymenski...Hitler did shoot himself and did bite into the cyanide capsule, just as Professor Haase had clearly and repeatedly instructed (Hitler and Hewel) to do. Pistol and poison, Q.E.D..."

- ^ The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared For Stalin From The Interrogations of Hitler's Personal Aides, New York, 2005, ISBN 1-58648-366-8

- ^ Karacs, Imre (May 4, 1998). "DNA test closes book on mystery of Martin Bormann, Independent, Bonn, 4 May 1998". London: Independent.co.uk. Retrieved April 28, 2010.