The Anathemata

| |

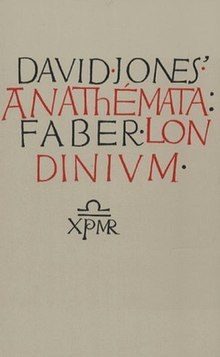

| Author | David Jones |

|---|---|

| Language | English, with some Latin and Welsh |

| Genre | Epic poem |

| Publisher | Faber and Faber |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Preceded by | In Parenthesis |

| Followed by | The Sleeping Lord and Other Fragments |

The Anathemata is an epic poem by the British poet David Jones, first published in England in 1952. Along with 1937's In Parenthesis, it is the text upon which Jones' reputation largely rests.

Summary

[edit]The poem is a symbolic, dramatic anatomy of historical western culture. Composed of eight sections, it narrates the thought processes of one cambrophile (lover of all things Welsh) English Catholic at Mass over the span of roughly seven seconds.[1]

Section I: "Rite and Fore-time" begins during a mid-twentieth century Mass, but quickly shifts to contemplate prehistoric ritual and myth-making. In the following sections, "Middle-sea and Lear-sea", "Angle-Land", and "Redriff", Jones' poem considers the theme of nautical navigation. Throughout, several ships in distinct historical periods sail westward from Troy to Rome (following the fall of Troy), then around Western Europe to the English coast (ca. 400AD), and finally to London via the Thames in the mid-nineteenth century.[2]

Section V, "The Lady of the Pool", is an extended monologue of sorts given by one Elen/Helen/Helena/Eleanore, a personification of the city of London, in the mid-fifteenth century. In section VI, "Keel, Ram, Stauros", the ship(s) we have been following explicitly becomes the World Ship, with the divine Logos for keel, and the Cross (stauros) as a mast.[3]

Finally, section VII, "Mabinog's Liturgy", concerns the Mediaeval Welsh celebration of Christmas Mass, while section VIII, "Sherthursdaye and Venus Day", centres on The Last Supper and Crucifixion.[4] While in this brief summary and indeed upon first reading[5] the poem's structure may seem chaotic, Thomas Dilworth has celebrated The Anathemata's wide-open form as unique in being formally whole. Dilworth notes that the structure produced by Jones' poetry is a "symmetrical multiple chiasmus," evident in Jones' manuscripts of the poem from its inception. He then provides the following illustration of its form:

((((((((O)))))))),[6]

in which the Eucharist--at center and circumference of this structure--is contained by and contains everything that the narrator daydreams about. Symbolically, the meaning of anything and everything has its ultimate expression in the sacrament, which confirms that meaning.

Allusions

[edit]"Anathemata" is Greek for "things set apart," or "special things." In lieu of any coherent plot, notes William Blissett, the eight sections of Jones' poem repeatedly revolve around the core history of man in Britain "as seen joyfully through Christian eyes as preparation of the Gospel and as continuation of Redemption in Christendom, with the Sacrifice of Calvary and the Mass as eternal centre."[7] This revolving structure reflects Jones' belief that cultural artefacts of the past lived on within specific cultures in a continuous line of artistic interpretation.[8] As such, the text is densely allusive, and moves freely between old/middle/early modern/modern English, Welsh, and Latin. In this respect, it is similar to The Cantos of Ezra Pound, or James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, and can confuse and mislead the over-attentive but impatient reader.[9]

Criticism

[edit]Thomas Dilworth has asserted that the reason that Jones' poetry is not widely read today is the "general neglect of The Anathemata."[10] This is owing to his publisher for decades not listing it as poetry or Jones as a poet. Despite this, The Anathemata was well received by Jones' fellow poets. For example, W.H. Auden described it as "very probably the finest long poem written in English this century," and T.S. Eliot felt that it secured Jones' status – along with Ezra Pound, and James Joyce – as a master of English Modernism.[11] John Berryman of the New York Times Book Review gave the poem a glowing review, calling it "sinewy, inventive, sensitive, vigorous, devoted, not at all a crackpot or homiletic operation. (...) I will not call it parasitic, for it enjoys its own materials; but is it epiphytic? Here is where criticism of the brilliant thing must begin."[12] Finally, the Times Literary Supplement also gave a favourable review, but also accurately forecasted Dilworth's lament that it would be ignored: the text "bristles with too many arcane allusions for a reader to grasp the meaning within its magic without a great deal of that 'mugging-up' which shatters the poetic illusion." [13]

References

[edit]- ^ Dilworth, Thomas (2008). Reading David Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780708320549.

- ^ Dilworth, Thomas (2008). Reading David Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780708320549.

- ^ Dilworth, Thomas (2008). Reading David Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 156. ISBN 9780708320549.

- ^ Dilworth, Thomas (2008). Reading David Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 160, 170. ISBN 9780708320549.

- ^ Thorpe, Adam (2008-06-12). "Book of a Lifetime: The Anathemata, by David Jones". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ Dilworth, Thomas (2008). Reading David Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 176–78. ISBN 9780708320549.

- ^ Blissett, William (1981). "Appendix A: 'In Medias Res,' University of Toronto Quarterly 24 (1955)". The Long Conversation: A Memoir of David Jones. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 152.

- ^ Noakes, Vivien (2007). "War Poetry, or the Poetry of War? Isaac Rosenberg, David Jones, Ivor Gurney". In Kendall, Tim (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of British and Irish War Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 134.

- ^ Blissett, William (1981). The Long Conversation: A Memoir of David Jones. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Dilworth, Thomas (2008). Reading David Jones. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780708320549.

- ^ Symmons, Michael (2002-09-28). "Poetry's Invisible Genius". The Telegraph. Jersey. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- ^ Berryman, John (1963-07-21). "Review of The Anathemata". The New York Times Book Review. New York. Retrieved 2017-09-05.

- ^ "Review of The Anathemata". The Times Literary Supplement. London. 1952-11-14. Retrieved 2017-09-05.