Théâtre des Tuileries

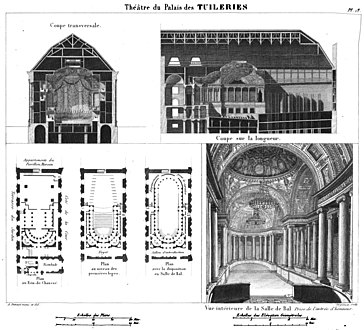

The Théâtre des Tuileries (French pronunciation: [teatʁ de tɥilʁi]) was a theatre in the former Tuileries Palace in Paris. It was also known as the Salle des Machines, because of its elaborate stage machinery, designed by the Italian theatre architects Gaspare Vigarani and his two sons, Carlo and Lodovico.[1] Constructed in 1659–1661, it was originally intended for spectacular productions mounted by the court of the young Louis XIV, but in 1763 the theatre was greatly reduced in size and used in turn by the Paris Opera (up to 1770), the Comédie-Française (from 1770 to 1782), and the Théâtre de Monsieur (from January to December 1789). In 1808 Napoleon had a new theatre/ballroom built to the designs of the architects Percier and Fontaine. The Tuileries Palace and the theatre were destroyed by fire on 24 May 1871, during the Paris Commune.

Salle des Machines

[edit]The auditorium, designed and decorated by the architects Charles Errard, Louis Le Vau, and François d'Orbay, was housed in a pavilion located at the north end of the palace as originally built by the architect Philibert de l'Orme for Catherine de Médicis.[2] Estimates of its seating capacity range from 6,000 to 8,000.[3] The unusually deep stage was located in a gallery situated between the auditorium and a new, more northern pavilion, later designated as the Pavillon de Marsan.[2]

The hall was inaugurated on 7 February 1662 with the premiere of Cavalli's Ercole amante. The costs of the project, including construction of the theatre, came to 120,000 livres, yet the opera was only performed eight times.[4] The theatre was not used again until January 1671, when Psyché, a scenically spectacular play with music and ballet, was presented. This production cost 130,000 livres and was only performed twice.[5] Psyché was reduced in size and successfully revived at the smaller Théâtre du Palais-Royal in July.[6] The Salle des Machines was not used again for musical theatre during the remainder of Louis XIV's reign. In 1720, during the Regency of Louis XV, the hall was remodeled again, at a cost of nearly 150,000 livres, and it hosted the court ballet Les folies de Cardenio with music by Michel Richard Delalande. The young King Louis XV made his first and last appearance in a dancing role in this production. After Cardenio there were no further productions, except for some marionette shows in the 1730s.[5] In view of the large expenditures on the theatre, it is surprising that it was so little used. Modern histories cite the poor acoustics, but Coeyman suggests that its disuse may have been the result of its large size: "the hall may have simply been too hard to fill."[7]

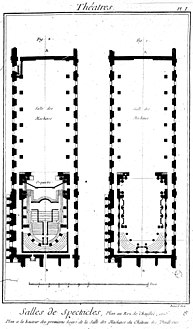

-

Plans of the Salle des Machines from Diderot's Encyclopédie (1772)

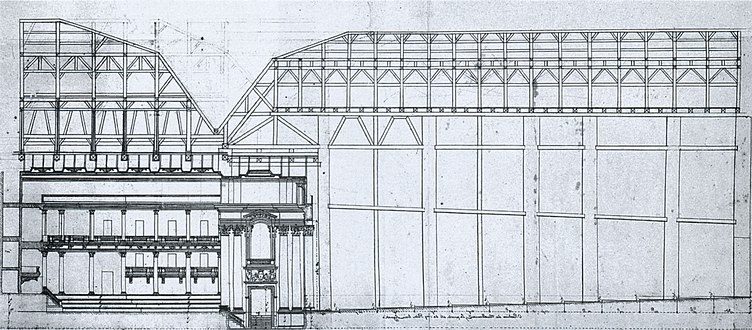

-

Long section of the Salle des Machines

Architectural history and composition

[edit]The Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon was torn down in 1660 to become the Louvre Colonnade. The walls of the Colonnade hosted the Théâtre des Tuileries. The theatre resided in the north wing of the Tuileries Palace. The palace was located to the west side of the Louvre from 1564-1883.[8] Louis XIV commissioned the Théâtre des Tuileries in 1659 with the intention of making a hall sizeable enough to put on the ballets he would be a part of to celebrate his marriage in 1660. Unfortunately the hall wasn't completed until 1661. The hall was to be long, rectangular and join the Louvre and Tuileries Palace. The joining was in Louis XIV's efforts to create a unified royal residence.[9] Efforts he later abandoned to put his focus towards the Palace of Versailles. Versailles offered more privacy compared to Paris's crowds, which Louis XIV preferred.[10]

Louis XIV hired Louis Le Vau somewhere between 1659-1661 to be the main architect on the project. Many of Le Vau's projects during the 17th century took on the likeness of French Baroque architecture, as they were an amalgamation of classical French and Baroque styles. Le Vau was influenced by Italian architecture and this appears in his building designs (i.e., classical aspects of order, balance, symmetry, and power.) An Italian scenic designer, Gaspare Vigarani was also a contributor to the Théâtre des Tuileries. Vigarani made his way from Italy to France to design the scenery for the theatre and build the stage in 1659.[11] Vigarani's scenic designs were made for both theatrical productions staged at the Théâtre des Tuileries and ballets. One of Vigarani's designs pioneered a machine made to satisfy Louis XIV's ego with an entrance nothing short of grand. The machine would elevate the royal family on a platform on which they sat in chairs, and lower them onto the stage.[12]

Thanks to both architects, the theatre became the largest theatre to exist in 17th century Europe. Its dimensions spanned 226 feet long and 132 feet deep with a 32 foot wide proscenium arch. Only 93 feet of that length was taken up by the auditorium.[13] If you measured from the start of the stage, the auditorium was 93 feet long by 52 feet wide by 42 feet high. The auditorium formed a square that ended in a semicircle for seating. The pit alone held 1,400 standing on-lookers. Three rows of steps surrounded the pit and led up to an amphitheater with over 1,200 seats (the baignoire). Two ranges of Corinthian columns and galleries stood on this amphitheater, whilst a third range stood on the second. Each range housed an amphitheater behind them exceeding 700 seats. The balustrades, cornices, and columns (base and capital) were decorated in gilt. The ceiling was home to the sculpting and gilt designed by Charles Le Brun and paintings rendered by Noël-Nicolas Coypel. A 137 foot long by 64 foot wide proscenium stage was home to box seating tucked to its side, composite columns of Ionic order, and an elliptical arch. The elliptical arch was just below an attic and a pediment. When entering the theatre, you are directed through a passage before you get to the main doors. In this passage you can get to the higher level seating via a grand staircase. Up the stairs, the first set of boxes you approach is a saloon with more ionic columns. Next to this saloon are similarly decorated box lobbies, and more stairs at the center to get to the galleries and royal box. The royal box is surrounded by three intercolumniations and protrudes in front of the colonnade. More box tiers can be found in-between the columns (Ionic) on the sides of the auditorium, decorated with green and gold draperies. On the very back walls behind the colonnade you'll find bas-reliefs. Four arches support an elliptical dome above, and shelter the third tier of boxes below. Four columns projecting outward hold up the arch vault of the proscenium.[14]

When it comes to decoration, every architectural surface is painted to mimic Breccia Violetta marble. Elements added to edges and surfaces are gone over with gilt. Each frieze and arch contain ornament (i.e., figures), the dome as well. The curtain on-stage is covered in ornamental designs. Many of this ornament is inspired by Roman architecture, which makes its first appearance in Paris in the fabrication of the Theatre of Tuileries.[15]

As for the future of the Théâtre des Tuileries, it underwent many changes up until it was purposefully set on fire in efforts to get rid of the past by Communards on 23 May 1871 during the Paris Commune.[16] One of these changes follows the succession of Vigarani by his son, Jean Bérain the Elder. Bérain went on to work with his son, Jean Bérain the Younger. The two brought a French style of scenic design that was characterized by heavy lines, curves, and overlaid ornament. It was typical of them to use only one set and many machines/spectacle for productions, a trend that follows through to 18th century French operas.[17]

A push for puritanism by the King in 1690 meant unpopularity of plays. With no need for the backstage space to fill with scenery and machinery anymore, the stage was later reduced by Jacques-Germain Soufflot and Jacques Gabriel in order to fit 1,500 more audience members into the auditorium.[18]

Later incarnations

[edit]

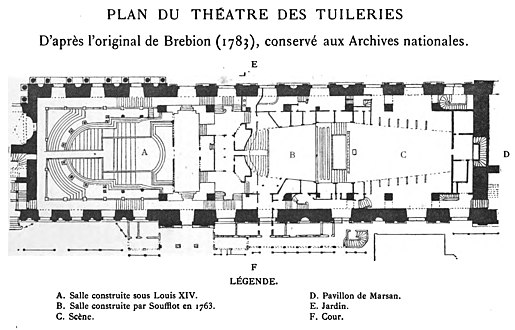

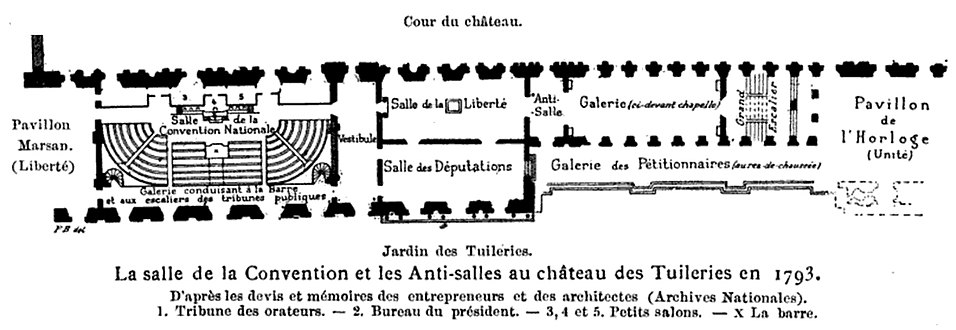

The theatre later underwent three substantial transformations: the first in 1763, when it was greatly reduced in size for the Paris Opera (to a capacity of 1,504 spectators) by the architects Jacques Soufflot and Jacques Gabriel;[19] the second begun in November 1792 and competed before 10 May 1793, when the National Convention moved from the Salle du Manège to the Salle des Machines;[20] and the third in 1808, when Napoleon had a new theatre built to the designs of the architects Percier and Fontaine.[21]

-

Modifications by Soufflot and Gabriel in 1763 (north to the right)

-

Hall of the National Convention in 1793 (north to the left)

-

Napoleon's theatre of 1808

Notes

[edit]- ^ Coeyman 1998, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Wild 1989, p. 404.

- ^ Coeyman 1998, p. 53. According to Wild 1989, p. 406, the number of places was 4,000 "d'ap. A. Donnet", but the latter author actually gives the capacity as 6,000 (Donnet 1821, p. 261).

- ^ Coeyman 1998, pp. 46, 55.

- ^ a b Coeyman 1998, p. 47.

- ^ Gaines 2002, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Coeyman 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Costa, Francisco (July 2013). "The Oxford Companion to Theatre and Performance. Edited by Dennis Kennedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. Pp. xiv + 689. £10.99/45 Hb". Theatre Research International. 38 (2): 160–161. doi:10.1017/S0307883313000060. ISSN 0307-8833.

- ^ Cole, Wendell (1962). "The Salle Des Machines: Three Hundred Years Ago". Educational Theatre Journal. 14 (3): 224–227. doi:10.2307/3204462. ISSN 0013-1989. JSTOR 3204462.

- ^ "Louis XIV". Palace of Versailles. 2024-02-19. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ "Theatre - France, Spain, Developments | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ alg.manifoldapp.org https://alg.manifoldapp.org/read/history-of-theatre-renaissance-spain-france/section/1b111c2c-270c-4873-ae33-dc9458843037. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Theatre - France, Spain, Developments | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ "Theatre Database / Theatre Architecture - database, projects". www.theatre-architecture.eu. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ "Theatre Database / Theatre Architecture - database, projects". www.theatre-architecture.eu. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ "Photograph: Ruins of the Tuileries Palace, Grand Vestibule and Place du Carrousel (May 1871)". napoleon.org. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ "Theatre - France, Spain, Developments | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ "The Salle des Machines (Palais des Tuileries) - History". Opéra national de Paris. Retrieved 2024-11-22.

- ^ Wild 2012, p. 406.

- ^ Lenôtre 1895, p. 95; Babeau 1895, p. 61.

- ^ Wild 1989, pp. 406–407.

Bibliography

[edit]- Babeau, Albert (1895). Le Théâtre des Tuileries sous Louis XIV, Louis XV, et Louis XVI. Paris: Nogent-le-Rotrou, Daupeley-Gouverneur. Copy at Google Books. OCLC 679305165.

- Coeyman, Barbara (1998). "Opera and Ballet in Seventeenth-Century French Theatres: Case Studies of the Salle des Machines and the Palais Royal Theater" in Radice 1998, pp. 37–71.

- Donnet, Alexis (1821). Architectonographie des théâtres de Paris. Paris: P. Didot l'ainé. Copy at Google Books.

- Gaines, James F., editor (2002). The Molière Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313312557.

- Lenôtre, Georges (1895). Paris révolutionnaire. Paris: Firmin-Didot. Copy at Google Books. OCLC 857906464.

- Radice, Mark A., editor (1998). Opera in Context: Essays on Historical Staging from the Late Renaissance to the Time of Puccini. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 9781574670325.

- Wild, Nicole (1989). Dictionnaire des théâtres parisiens au XIXe siècle: les théâtres et la musique. Paris: Aux Amateurs de livres. ISBN 9780828825863. ISBN 9782905053800 (paperback). View formats and editions at WorldCat.

- Wild, Nicole (2012). Dictionnaire des théâtres parisiens (1807–1914). Lyon: Symétrie. ISBN 9782914373487. OCLC 826926792.